Approach

Clinical history and presentation can vary significantly depending on the age of the child and the size of the ductus. Patients may be entirely asymptomatic or have signs and symptoms of heart failure and haemodynamic instability.

History

The clinical history varies depending on the age of the patient and the size of the shunt.

In premature babies the clinical history can be somewhat non-specific. They can have worsening respiratory status with tachypnoea and/or apnoea and increased ventilation requirements. They can also have circulatory instability associated with low diastolic blood pressure (BP), which may mimic sepsis.

In full-term infants and children with a small patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) there may be no significant clinical history.

With a moderate or large PDA, infants may present with non-specific symptoms such as tachypnoea, irritability, poor feeding, diaphoresis, and failure to gain weight. They may be prone to increased respiratory symptoms with upper respiratory tract infections. An older child or adult may present with shortness of breath and exercise intolerance.[38][39]

Physical examination

Irrespective of size, PDA in the newborn is associated with a murmur heard only during systole. However, the murmur later becomes more continuous in nature.

Small ductus: on cardiac examination, there is usually normal precordial activity with a normal S1 and S2. A continuous murmur is best heard in the second left intercostal space. It may radiate to the back. The murmur is accentuated late in systole and continues into diastole.[40] The lung examination and respiratory rate are usually normal.

Moderate or large ductus: these children usually have a hyperdynamic precordium. A systolic thrill may sometimes be palpable in the upper left sternal border. The first and second heart sounds are sometimes masked by the murmur. A third heart sound is often heard at the apex. There may also be a mid-diastolic rumble heard at the apex. The peripheral pulses are often bounding. On respiratory examination, these children may be tachypnoeic. If they are in heart failure they may have pulmonary rales.

On BP measurement there may be a widened pulse pressure if the ductus is large.

Diagnostic testing

Generally, if there is concern for a PDA based on clinical findings, a chest x-ray (CXR) and ECG may be helpful in providing information with regard to the presence or absence of a clinically significant shunt. The definitive diagnostic test, however, is an echocardiogram.[32][39]

Chest x-ray (CXR)

A CXR in a patient with a moderate or large haemodynamically significant ductus will demonstrate an enlarged heart and increased pulmonary vascular markings. The main pulmonary artery segment will be prominent. Left atrial dilation, best seen on the lateral film, will be present. In patients with smaller shunts, the CXR can be completely normal.

ECG

During early infancy, the ECG is often normal. However, in older infants and children it may demonstrate left ventricular enlargement, with a deep Q wave and tall R waves in leads II, III, aVF, V5, and V6. Left atrial enlargement with widened P waves may also be seen. Findings are non-specific, as they can be seen with other left-sided shunts such as ventricular septal defects. In patients with smaller shunts, the ECG can be completely normal.

Echocardiogram

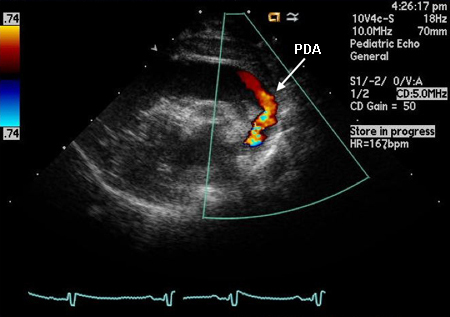

The definitive test to confirm diagnosis is an echo.[32][41] In children, this should be performed by a sonographer trained in congenital heart disease (CHD) in conjunction with a paediatric cardiologist; alternatively, a referral to a paediatric cardiologist should be made.[42] Echocardiography can confirm the presence and size of the ductus as well as the direction of shunting. It is important to determine the direction and velocity of the shunt in order to understand the degree of ductal resistance and relative systemic to pulmonary pressure. Left heart chamber dimensions can be evaluated to determine the significance of the duct. In the early days of echo, sensitivity was 96% and specificity was 100% compared with angiography.[43] However, in the present era, with echo’s improved capabilities, it is accepted as 100% sensitive, with angiography and catheterisation reserved for treatment purposes only.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Echo of a 26-week premature infant demonstrates colour Doppler flow from the systemic circulation (aorta) through the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) to the left pulmonary arteryNelangi M. Pinto, MD; used with permission [Citation ends]. Early antenatal detection of CHD through echocardiography enables timely planning for neuroprotective strategies during neonatal care, which may alleviate some neurodevelopmental impacts associated with CHD.[8]

Early antenatal detection of CHD through echocardiography enables timely planning for neuroprotective strategies during neonatal care, which may alleviate some neurodevelopmental impacts associated with CHD.[8]

Cardiac catheterisation and angiography

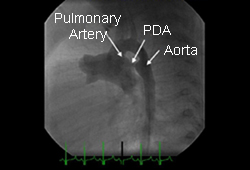

Cardiac catheterisation with angiography is usually not necessary for the diagnosis of an uncomplicated PDA. The role of this procedure in most cases is the facilitation of closure via transcatheter occlusion. If used diagnostically, it provides evidence of the presence and severity of shunt and allows assessment of any associated pulmonary hypertension. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lateral angiogram of 1-year-old child demonstrates flow of contrast from the aorta through a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) to the pulmonary circulationNelangi M. Pinto, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

Emerging tests

One Cochrane review found that a simple blood assay for brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) had moderate accuracy in the diagnosis of haemodynamically significant PDA. However, the studies evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of these assays varied considerably by assay characteristics and patient characteristics; hence, generalisability between centres is not possible and further studies are needed.[44]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer