Aetiology

Coarctation of the aorta is primarily a congenital malformation. Increased attention is being focused on coarctation being part of a more diffuse arteriopathy, and careful attention to the morphology of the aortic valve (often bicuspid) and ascending aorta is imperative.[6]

The aetiology of congenital coarctation is incompletely understood, but 2 primary theories explain the narrowed segment:

The narrowed segment is under-developed during fetal life due to reduced blood flow across the developing arch. This is particularly thought to be responsible when associated with additional left-sided lesions such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

Ductal tissue extends into the thoracic aorta, and, when the ductus arteriosus constricts and closes postnatally, the thoracic aorta is constricted.[7]

Much less commonly, aortic coarctation can be acquired. Takayasu arteritis, a large vessel vasculitis, can result in aortic coarctation. In these cases, the narrowed segment is often in the descending thoracic or abdominal aorta.[8] Rarely, severe atherosclerotic disease can result in aortic obstruction with pathophysiological consequences similar to coarctation.

Pathophysiology

The effects of aortic coarctation depend on the severity of the narrowing and resultant elevated after-load on the left ventricle.

Severe narrowing of the aortic arch that presents in the neonatal period with low output cardiac failure and shock once the ductus arteriosus closes is termed critical coarctation. These infants require a prostaglandin E1 infusion to maintain a patent ductus arteriosus and surgical repair after medical stabilisation.

Mild and moderate narrowing can be clinically silent for many years; however, the hypertension associated with coarctation can have long-standing effects of hypertensive vascular disease even after the narrowed segment is repaired. Collateral blood vessels often enlarge and provide a route for blood to bypass the narrowed segment of the aorta. Indications for repair are congestive heart failure, systolic hypertension, or a peak pressure gradient >20 mmHg across the coarctation measured by Doppler echocardiography or catheterisation.[9] Repair can be surgical or percutaneous depending on the patient's age and presentation.[10]

Classification

Site of coarctation

1. Juxtaductal

Most common

Narrowing is at the insertion site of the ductus arteriosus.

2. Other (preductal, infrarenal, abdominal)

Less common

Narrowing can be proximal to the left subclavian artery or in the abdominal aorta.

3. Tubular hypoplasia

Rare

Long segment of narrowing.

Exact location of the narrowing in relationship to the ductus arteriosus

Narrowing at the ductus is termed juxtaductal, which has also been termed an infantile coarctation.

Narrowing proximal to the ductal insertion is termed a pre-ductal coarctation and is typically associated with hypoplasia of the transverse arch.

Post-ductal coarctations occur distal to the ductal insertion.

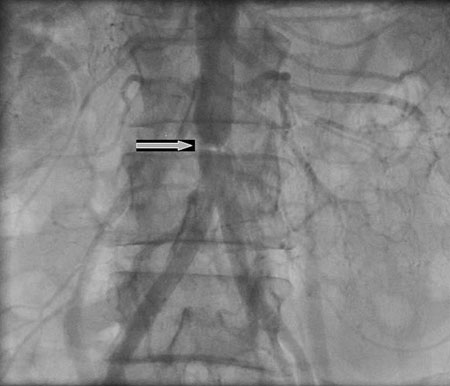

An abdominal coarctation occurs in the abdominal aorta and may be associated with narrowing of the abdominal aortic vessels.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal coarctationN. Pal, D. McEneaney. BMJ Case Reports 2009 [Citation ends].

Presence of associated abnormalities

A third classification has been proposed that combines the anatomical features of the coarctation with the presence of associated anomalies:[1]

Type I: coarctation with or without patent ductus arteriosus (PDA)

IA: with ventricular septal defect (VSD)

IB: with other major cardiac defects.

Type II: coarctation with isthmus hypoplasia, with or without PDA

IIA: with VSD

IIB: with other major cardiac defects.

Type III: coarctation with tubular hypoplasia of the isthmus and segment between left carotid and subclavian arteries, with or without PDA

IIIA: with VSD

IIIB: with other major cardiac defects.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer