Approach

The diagnosis of sexual abuse and sexual assault is complex and has major ramifications; it is therefore important to follow diagnostic guidelines.

Initial assessment of child victims of sexual abuse includes psychosocial and medical components, and varies according to the child's pubertal status and the time elapsed since the most recent sexual contact. For all paediatric patients, providers must ensure that the child will be returning to a safe environment and that mandatory reporting to the relevant child protection agency has been done.

Patients may report sexual assault soon after the assault, or they may later seek medical care without necessarily disclosing why, unless specifically but sensitively asked. Post-assault medical care should include meeting healthcare needs, and in acute cases, evidence collection for medico-legal purposes if the patient consents. Good documentation is crucial, and can be supported by the availability of standardised forms for record-keeping.[31] Rape is a profoundly disempowering experience, and it is essential that care is provided in a way that supports individuals in reclaiming control over their lives.

Associated symptoms and behaviours

A child may display changes in their typical behaviour. The stress of sexual abuse may manifest as depressive symptoms, acting-out behaviour, or chronic medical complaints. The following may be signs of sexual abuse, although they are non-specific and the strength of association with child abuse is not quantified.

Sexual behaviour problems: many sexualised behaviours are developmentally normal. Examples of behaviours that may be associated with sexual abuse include sexual behaviours that are coercive, persistently intrusive, developmentally abnormal, or abusive.[32][33]

Symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder: suicidal ideation should also be assessed.[34]

Chronic medical complaints: may be an indicator for child psychological stress.

Frequent or persistent genito-urinary complaints: may be an indicator of child psychological stress or sexually transmitted infection.

Children who are being sexually exploited may present with additional findings such as: unexplained or patterned injuries or tattoos; a history of running away from home; a false or changing history including a lack of identifying documents or home address; a history of multiples STIs or pregnancies; or possession of large amounts of cash. Suspicion should also be raised if there is a significant age difference between the patient and sexual partner, or if a person other than the patient insists on providing the history.[35]

Adults who have been sexually abused (as children or more recently) may present with emotional and psychological problems such as depression or substance misuse, or physical symptoms such as chronic pelvic pain.[36] After sexual assault, early symptoms include stress, anxiety, self-blame, and guilt. Longer-term problems include depression, eating disorders, sleep disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance misuse, and thoughts or acts of self-harm or attempted suicide.[37][38]

Interviewing

Children and adults should be asked about possible sexual abuse and assault in a non-leading manner, with open-ended questions. Interviewing a child includes use of age-appropriate language and thorough documentation of the questions and the child's responses. It is preferable to record disclosures from both children and adults in their own words, rather than in a summary statement.[34] Interviewers should maintain professional and non-emotional reactions to the child’s answers.[39][40]

Physical examination when sexual abuse and assault is suspected

If child sexual abuse and assault is suspected, a referral to a hospital with a specialised abuse assessment clinic should be considered.[34] The American Academy of Pediatrics has set out detailed guidance for paediatricians carrying out anogenital examinations.[34] Physical examination findings are most often normal in victims of child sexual abuse.[41][42][43] However, sexual abuse may be among the differential diagnoses to consider if one of the following findings is noted on examination:

Vaginal discharge

Anogenital lesions or dermatological findings

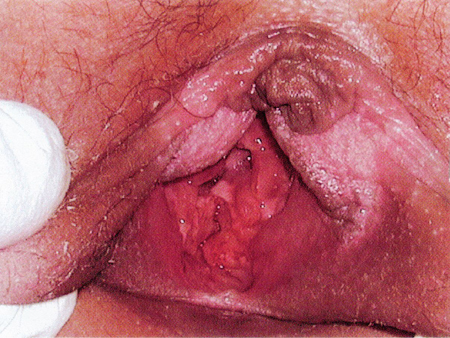

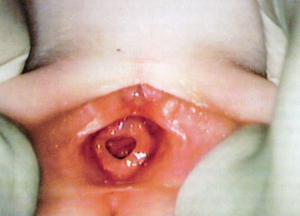

Hymenal abnormalities or anogenital trauma.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Absent hymen from 4 to 7 o'clock position in a sexually active 14-year-old girlGirardet RG, et al. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2002;32:211-246. Used with permission [Citation ends].

Adolescents develop pubertal changes along a predictable progression. Secondary sexual characteristics are classified according to sexual maturity rating (SMR). Pre-adolescent or (pre-pubertal) children have not yet begun puberty and are SMR stage 1. Adolescents are at SMR stage 3 and over. The distinction between pre-pubertal children and adolescents is clinically important due to effects on physical examination, evaluation, and treatment. For example, speculum examinations should not be used in pre-pubertal children in the office setting.[34]

In adult women who have been sexually assaulted, injuries are found in about half of cases and are seen more commonly in older victims.[44][45][46] Non-genital injuries are more common than genital injuries. The absence of injury does not imply consent or exclude penetration, even in women who deny previous sexual activity. Evidence of sexually transmitted infections in these patients may represent the assailant’s secretions or previous sexual contact.

Acute presentation: ≤72 hours since abuse or assault

Psychosocial assessment should include:

Evaluation of discharge arrangements to ensure that the child or adult will be returning to a safe environment

Referral for psychological/social services is also recommended.

Medical evaluation (with consent) should include:

Complete physical examination to assess for possible injuries or other medical conditions. Children who have been sexually abused and assaulted may be at risk of other types of abuse and neglect. It is therefore recommended that a thorough general physical examination should follow the anogenital examination.[34]

Collection of forensic evidence specimens. Samples such as a mouth swab for the perpetrator’s DNA, and urine and blood for toxicology should be collected as soon as possible following sexual assault when indicated. In cases of sexual abuse involving pre-adolescent children, evidence is more likely to be found on objects present at the assault (e.g. bedding or clothing) than on the child's body.

Baseline testing for HIV and syphilis.

Baseline measurement of liver function tests, full blood count, serum urea, and serum creatinine prior to commencement of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis.

Pregnancy test for females of reproductive age.

Testing for sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

Adolescents may be tested for STIs at the time of presentation. However, detection of an STI may represent an infection acquired before the assault and/or infection in the assailant’s secretions. Empirical prophylactic treatment should be considered, as compliance with follow-up visits is traditionally poor.[47]

Pre-adolescent children evaluated for acute sexual assault should be tested for STIs based on the history of the assault and clinical manifestations of an infection.[48] Prophylactic treatment is not generally offered to pre-pubertal children due to the decreased transmission rates of STIs and the evidentiary value of a positive test in a child who cannot legally consent.[31]

Tests should include the following: Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, syphilis, hepatitis C, and HIV.[48] If ulcers or vesicles are present, specimens for viral culture should be collected. If a vaginal discharge is present, testing for trichomonas, bacterial vaginosis, Candida, and aerobic culture should be done. Tests for hepatitis C, syphilis, and HIV may not be positive until 3 to 6 months after infection.

Hepatitis B

For children and adolescents in countries with universal vaccination for hepatitis B, testing for hepatitis B antibodies is usually not required. In countries without universal vaccination, or if there is no record of hepatitis B vaccination, a test for hepatitis antibodies to determine the need for hepatitis B immunoglobulin or vaccine should not delay the administration of hepatitis B vaccine or immunoglobulin. If required, hepatitis B vaccine may be provided up to 3 weeks after the assault as the hepatitis B virus has a long incubation period.[31] If there is no history or proof of hepatitis B vaccination, hepatitis B immunoglobulin should be administered in addition to vaccination if the assailant is hepatitis B surface antigen positive. Arrangements should be made for subsequent doses of hepatitis B vaccine to be given.

Forensic examination

A forensic examination should be strongly considered for any child, adolescent, or adult, and undertaken as soon as practicable. The recommended timing of the examination depends on the sample type and local jurisdictions; paediatricians should familiarise themselves with their relevant policy. Most protocols recommend that forensic evidence should be collected if less than 72 hours have passed since the assault but some are as late as 168 hours.[34][38][49]

Initial history includes a general medical and social history. All individuals in the room at the time of questioning regarding the sexual assault should be noted. Questions should be carefully documented, non-leading, and open-ended, and responses noted verbatim in the chart.

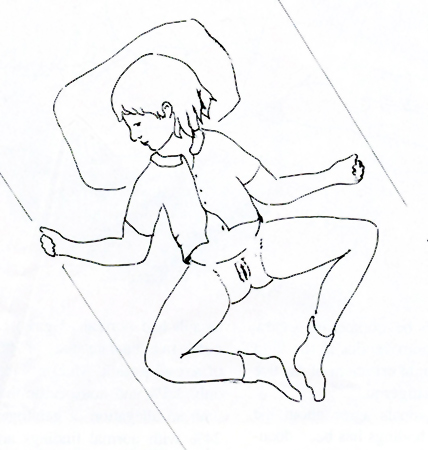

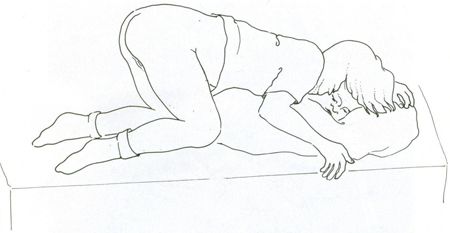

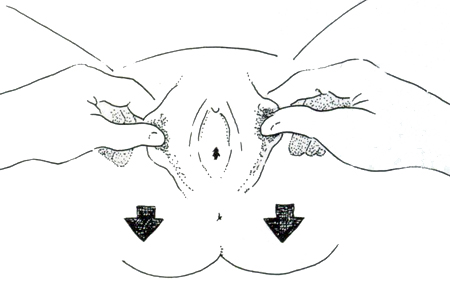

A complete but sensitive examination should be performed, including a thorough examination of the skin to note any traumatic findings. Ideally the anogenital examination is performed with a colposcope (or comparable magnification device) that has a photographic capability. All injuries should be carefully documented using agreed nomenclature and body diagrams. The supine frog-leg position is used for the genital examination of pre-pubertal girls; any abnormal hymenal findings should be confirmed using the prone knee-chest position. Adolescent girls and women are generally examined in the lithotomy position. The use of labial traction greatly enhances visualisation of the hymen.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Acute vaginal trauma in an 11-year-old victim of abduction and rapeGirardet RG, et al. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2002;32:211-246. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Supine frog-leg position for examination of a pre-pubertal girlGirardet RG, et al. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2002;32:211-246. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Supine frog-leg position for examination of a pre-pubertal girlGirardet RG, et al. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2002;32:211-246. Used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Knee-chest position for examination of a pre-pubertal girlGirardet RG, et al. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2002;32:211-246. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Knee-chest position for examination of a pre-pubertal girlGirardet RG, et al. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2002;32:211-246. Used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Labial traction techniqueGirardet RG, et al. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2002;32:211-246. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Labial traction techniqueGirardet RG, et al. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2002;32:211-246. Used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Normal annular hymenGirardet RG, et al. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2002;32:211-246. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Normal annular hymenGirardet RG, et al. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2002;32:211-246. Used with permission [Citation ends].

Forensic evidence collection kits are available in most hospital emergency departments, and include packets in which to send specimens of blood, hair strands and combings, and fingernail, pharyngeal, genital, and anal swabs to a forensic laboratory. In some countries, forensic examination and aftercare are provided in specialist sexual assault centres. The clothing worn at the time of the assault, as well as associated bedding and other samples such as tampons, may also contain forensic evidence.[31]

Non-acute presentation: >72 hours after abuse or assault

Psychosocial assessment is the same as for patients presenting <72 hours after the abuse or assault. The medical and forensic evaluation (with consent) should include the following investigations:

Complete physical examination to assess for possible injuries or other medical conditions.

A forensic examination, if indicated by regional or national protocols. Recommendations about the timeframe within which collection of forensic evidence specimens (cervical and vaginal samples) from post-pubertal females can be performed differ between regions. Most protocols recommend that forensic evidence should be collected if less than 72 hours have passed since the assault, but some are as late as 168 hours.[34][38][49] When indicated, a forensic examination should be carried out in the same way as for patients presenting <72 hours after the abuse or assault.

Testing for chlamydia and gonorrhoea.

If ulcers or vesicles are present, a specimen for viral culture or DNA for herpes simplex virus should be collected.

If vaginal discharge is present, testing for trichomonas, bacterial vaginosis, Candida, and aerobic culture should be performed.

Serological testing for HIV and syphilis. These tests may not be positive until 3 to 6 months after infection.

Testing for pregnancy in females of reproductive age.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Example of the use of a body diagram to record injuriesWelch J, Mason F. BMJ 2007;334:1154-1158 [Citation ends].

The clinical significance of physical findings in children

The classification scheme proposed by Joyce Adams et al may be used to determine the significance of physical findings.[50][51][52]

Normal variants include:

Peri-urethral or vestibular bands, intravaginal ridges or columns, hymenal bumps or mounds, hymenal tags, septal remnants, linea vestibularis, hymenal notch or cleft (regardless of depth) above the 3 and 9 o’clock location of the hymen, superficial notch of the hymen at or below the 3 and 9 o’clock location of the hymen, external hymenal ridge, congenital variations in hymenal appearance (crescentic, annular, redundant, septate, cribriform, microperforate, imperforate), diastasis ani, hyperpigmentation of labia minora or peri-anal tissues, dilation of the urethral opening with labial traction, thickened hymen.

Findings commonly caused by other medical conditions include:

Erythema, increased vascularity, labial adhesions, vaginal discharge, friability of the posterior fourchette or commissure, excoriations, bleeding or vascular lesions, perineal groove (failure of midline fusion), molluscum contagiosum, anal fissures, venous congestion or venous pooling in the peri-anal area, flattened anal folds, partial or complete anal dilation.

Indeterminate findings include:

Deep notches or clefts in the posterior/inferior rim (between 3 and 9 o'clock) of the hymen in pre-pubertal girls

Deep notches or complete clefts in the hymen at 3 or 9 o'clock in adolescent girls

Complete clefts/transections at 3 or 9 o’clock

Wart-like lesion in the genital or anal area

Vesicular lesions or ulcers in the genital or anal area

Marked, immediate anal dilation.

Findings suggestive but not diagnostic of sexual contact include:

Genital or anal condyloma acuminatum: the specificity for sexual transmission is indeterminate if there are no other indicators of abuse. Lesions appearing for the first time in a child older than 5 years of age may be more likely to be the result of sexual transmission.

Herpes type 1 or 2 in the genital or anal area: may be innocently transmitted, auto-inoculated, or sexually transmitted. The presence of the infection is not diagnostic of sexual contact in a child with no other indicators of abuse.

Findings diagnostic of trauma and/or sexual contact include:

Acute trauma to external genital or anal tissues, such as acute lacerations or extensive bruising of labia, penis, scrotum, peri-anal tissues, or perineum and fresh laceration of the posterior fourchette, not involving the hymen.

Residual (healing) injuries include the following:

Peri-anal scar, and scar of posterior fourchette or fossa.

Injuries indicative of blunt force penetrating trauma (or abdominal/pelvic trauma) include:

Laceration of the hymen

Acute ecchymosis, petechiae, or abrasion on the hymen

Hymenal transection (healed) between 4 and 8 o'clock of the hymenal rim, and missing segment of hymenal tissue

Peri-anal laceration with exposure of tissue below the dermis.

Presence of infection confirms mucosal contact with infected and infective bodily secretions, contact most likely to have been sexual in nature:

Positive confirmed culture for gonorrhoea from genital area, anus, or throat outside the neonatal period.

Positive culture from genital or anal tissues for chlamydia, if child is older than 3 years at time of diagnosis and specimen was tested using cell culture or comparable approved method.[47]

Confirmed Trichomonas vaginalis infection in a child older than 1 year of age.

Confirmed syphilis if perinatal transmission is ruled out.

Positive confirmed serology for HIV if perinatal transmission, transmission from blood products, and needle contamination have been ruled out.

Other laboratory findings diagnostic of sexual contact include:

Positive pregnancy test

Sperm identified in specimens taken directly from a child's body.

Trauma in adults

Injuries have been reported in about half of adults reporting sexual assault; they are more common in older women.[44][45][46] Non-genital injuries are more common than genital injuries. The absence of injury does not imply consent or exclude penetrative intercourse, even in people who deny previous sexual activity.

Injuries are usually minor but may need treatment. They should be documented: for example, using a body diagram to record measurements, a description, and position in relation to anatomical sites.

Major injuries, for example, head trauma, are rare but may be life-threatening, and their management must take precedence over forensic examination. Occasionally someone may present with vaginal or anal bleeding following penetration with a penis or foreign body. Such individuals should be assessed in an acute hospital setting with resuscitation facilities, and may require examination under anaesthesia and operative repair.

Online resources

Canadian Paediatric Society: the medical evaluation of pre-pubertal children with suspected sexual abuse Opens in new window: position statement providing an evidence-based, trauma-informed approach to the medical evaluation of pre-pubertal children with suspected or confirmed sexual abuse.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer