Approach

The following considerations apply to ileocaecal intussusception only (i.e., an intussusception that involves the distal ileum, typically with the caecum, ascending and transverse colon). Primary treatment is always by contrast enema (gas or liquid) unless there are signs of peritonitis, which necessitates early surgery.[28] In pure small bowel intussusception (e.g., ileo-ileal), or in intussusception that occurs in association with a pathological lead point, different considerations apply. An ileo-ileal intussusception may be seen coincidentally during or after a laparotomy (typically retroperitoneal surgery). If this is not the case, and the child has presented symptomatically, then radiologic reduction is less likely to be successful as it is more difficult to generate sufficient pressure in the more proximal bowel.[29] Similarly, when a pathological lead point is suspected, surgical resection is likely to be required depending on the nature of the lead point.[1] Resection will also reduce the chance of recurrence.

Treatment of paediatric intussusception should be initiated at the time of diagnosis. The goal is correction of hypovolaemia and electrolyte abnormalities, followed by urgent reduction. Reduction can be accomplished with contrast enema (air or contrast liquid) or by surgery.

Fluid resuscitation

Initial treatment includes obtaining adequate intravenous access and correction of hypovolaemia with isotonic fluid resuscitation.

Antibiotics

The role of antibiotics is unclear. In some centres they are no longer routinely indicated in children with intussusception, unless there is coexistent septic shock or manifestations of intestinal perforation. In others, the potential for poorly perfused or dilated bowel to translocate and produce a bacteraemia is seen as an indication. Administration of prophylactic antibiotics before enema reduction does not appear to reduce the risk of post-reduction complications.[28] When indicated, broad-spectrum antibiotics covering intra-abdominal pathogens should be administered.

Administer antibiotics 1 hour before the procedure if possible, and then consider continuing antibiotics after reduction for up to 48 hours if ischaemia or significant dilatation is present.

For patients who undergo resection, use routine intestinal prophylactic regimens Prolonged antibiotic administration is only recommended in cases of perforation or abscess formation.

Contrast enema reduction

Contrast enema (air or liquid contrast) should be performed only in patients who are clinically stable. Complications of contrast enema reduction include perforation and failure of reduction, both necessitating surgical intervention. Risks associated with radiation exposure should be considered.

Absolute contraindications: peritonitis, perforation, toxic colitis, and hypovolaemic shock.[27]

Relative contraindications: prolonged symptoms, ultrasound findings of intestinal ischaemia or trapped fluid, and marked evidence of bowel obstruction (e.g., abdominal distension, signs on imaging).[27] The procedure requires some cooperation from older children, who may not be able to tolerate the discomfort of the procedure.

Factors that suggest a lower reduction rate and higher perforation rate include patient age <3 months or >5 years, long duration of symptoms (>48 hours), passage of blood via the rectum, significant dehydration, small-bowel obstruction, and visualisation of a coiled spring sign.[20]

Reduction should be first attempted by contrast enema (air or liquid contrast), which can be both diagnostic and therapeutic. Pneumatic reduction is considered the method of choice for the treatment of intussusception in stable patients provided that there is no indication for surgical reduction.[30][31] Protocols typically vary by institutions but often involve instillation of air and/or contrast at pressures ranging from 80 to 120 mm Hg.[27] The patient should be kept nil by mouth.

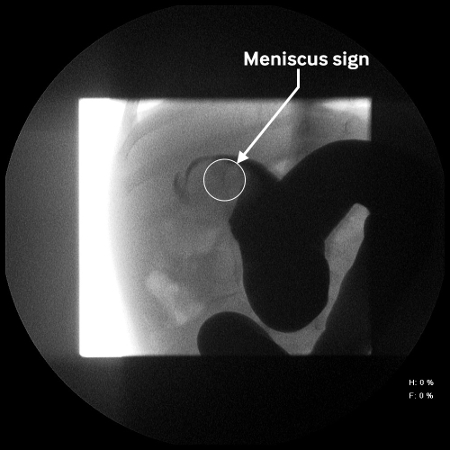

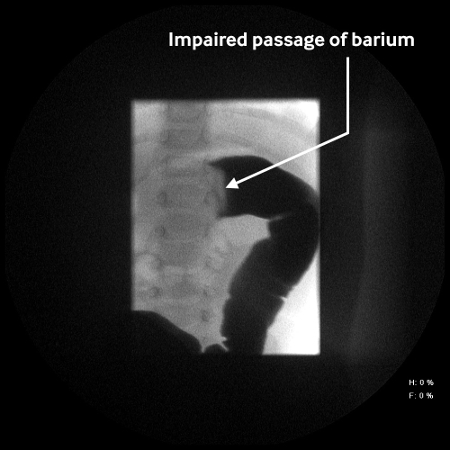

Methods of therapeutic enemas have varied over time. Reduction by contrast enema has classically been performed with either liquid (water-soluble contrast or barium) or air. Saline enemas and ultrasound-guided enemas have had success, reducing the radiation burden. Rates of successful reduction and complications with this technique could not be directly compared with other methods of contrast enema reduction due to lack of standardisation between studies.[21][22] However, one Cochrane review of two studies found air to be more effective than liquid contrast (low-quality evidence base).[22][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Site of intussusception as revealed by abdominal x-ray, showing the meniscusFrom the collection of Dr David J. Hackam; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray showing impaired passage of barium at site of obstruction due to intussusceptionFrom the collection of Dr David J. Hackam; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal x-ray showing impaired passage of barium at site of obstruction due to intussusceptionFrom the collection of Dr David J. Hackam; used with permission [Citation ends].

Barium enema: advantages over other types of contrast enema reduction include a long-standing experience in some centres, effective reduction in most cases, good evaluation for residual intussusception, and a low perforation rate. Disadvantages include the need for x-ray exposure, chemical peritonitis in the event of a perforation, and visualisation of only intraluminal content. Water-soluble contrast enema has been used to reduce the risk of chemical peritonitis resulting from perforation. Reduction rate and perforation rate are comparable with other contrast agents.

Air enemas: less radiation required and similar rates of failure, recurrence, and perforation to other agents.

Ultrasound-guided saline enema: excellent results have been described with the use of this modality, which offers the advantage of limiting exposure to radiation.[30][32] Although there is less experience with this method than fluoroscopic reduction, it is being used with increasing frequency.[20][21][31][32][33]

Surgical reduction

If peritonitis is present, immediate surgical consultation and resuscitation is advised.[28] Abdominal plain-film x-rays should be assessed for the presence of pneumoperitoneum. Patients with contraindications to contrast enema reduction should undergo urgent surgical evaluation. Surgical reduction has been successfully performed using laparoscopic as well as traditional open approaches.[28]

Traditionally, operative reduction has been performed through an open approach via a right lower quadrant incision. The intussusception is identified and milked out of the intussuscipiens. Successful laparoscopic reduction has been described and is becoming popular; the intussusceptum is reduced by applying gentle traction.[34][35] The requirement for intra-abdominal pressure means that laparoscopic surgery would not be considered in a clinically unstable patient.[28] Intestinal resection may be necessary for cases complicated by bowel necrosis and perforation.

Recurrence

Most recurrences after successful reduction of intussusception occur soon after reduction. The recurrence rate of intussusception after contrast enema (air or liquid contrast) reduction is approximately 10% and does not significantly differ based on the type of contrast reduction performed.[36] The risk of recurrence within 48 hours is low after enema reduction suggesting that patients who appear well should be considered for outpatient management with follow-up.[37][38]

Surgical reduction has been associated with a recurrence rate of 2% to 5%.[39]

One Cochrane review evaluated evidence from two studies investigating the use of steroid medication, such as dexamethasone. The review found that steroid administration may reduce the recurrence of intussusception but further research is needed to confirm these results.[22]

Although suspicion for a pathological lead point must be increased with a recurrent intussusception, successful contrast enema reduction has been advocated. Surgical intervention is reserved for irreducible recurrences and the presence of an identified pathological lead point.[2][36] After an infant's third episode of intussusception, a pathological lead point must be considered. Computed tomography may be useful in evaluation for a pathological lead point.[19]

In older children with intussusception, pathological lead points must be considered. Diseases such as cystic fibrosis and Henoch-Schonlein purpura can cause bowel-wall abnormalities that function as lead points in intussusception.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer