The diagnosis of TSC is made by clinical examination and/or genetic testing.[18]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

This is supported by neuroimaging and other investigations (echocardiogram, renal ultrasound, dilated ophthalmoscopy, etc.). The additional investigations are utilised to confirm the diagnosis, determine disease extent, delineate organ involvement, and clarify parental recurrence risks over time.

History

There are no symptoms that are specific for TSC. However, there are several common presentations that should prompt consideration of TSC and further investigation.[18]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Gomez M, Sampson J, Whittemore V, eds. The tuberous sclerosis complex. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999.[3]Hyman MH, Whittemore VH. National Institutes of Health consensus conference: tuberous sclerosis complex. Arch Neurol. 2000 May;57(5):662-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10815131?tool=bestpractice.com

First and foremost is identification of a family member with TSC. A three-generation family history should be obtained.[18]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

If the family member is a first-degree relative (i.e., a parent), a 50% chance exists for the patient under evaluation to have the disorder. This 50% risk remains when multiple siblings are affected, and assumes that one parent unknowingly has the disorder or there is gonadal mosaicism in one of the parents. Gonadal mosaicism is a condition whereby the only organs affected with the TSC mutation are the gonads and their affected gametes, allowing the potential for multiple affected children from an otherwise unaffected parent.[13]Tyburczy ME, Dies KA, Glass J, et al. Mosaic and intronic mutations in TSC1/TSC2 explain the majority of TSC patients with no mutation identified by conventional testing. PLoS Genet. 2015 Nov;11(11):e1005637.

https://journals.plos.org/plosgenetics/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgen.1005637

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26540169?tool=bestpractice.com

[19]Nathan N, Keppler-Noreuil KM, Biesecker LG, et al. Mosaic disorders of the PI3K/PTEN/AKT/TSC/mTORC1 signaling pathway. Dermatol Clin. 2017 Jan;35(1):51-60.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27890237?tool=bestpractice.com

The incidence of gonadal mosaicism in individuals with TSC is estimated to be around 2%.[20]Julie LN, Maja PS, Lisbeth BM, et al. Mosaicism in tuberous sclerosis complex: a case report, literature review, and original data from Danish Hospitals. EMJ Dermatol. Nov 2021;9[1]:98-105.

https://www.emjreviews.com/dermatology/article/mosaicism-in-tuberous-sclerosis-complex-a-case-report-literature-review-and-original-data-from-danish-hospitals

Other historical factors include:

Multiple hypomelanotic macules with concurrent epilepsy or autism[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hypomelanotic macules and shagreen patchCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

Infantile spasms

Cardiac rhabdomyoma(s)[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cardiac rhabdomyoma on sagittal T1 MRICourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

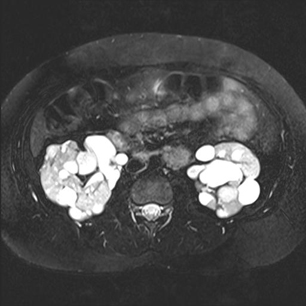

Polycystic kidney disease[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Polycystic kidneysCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

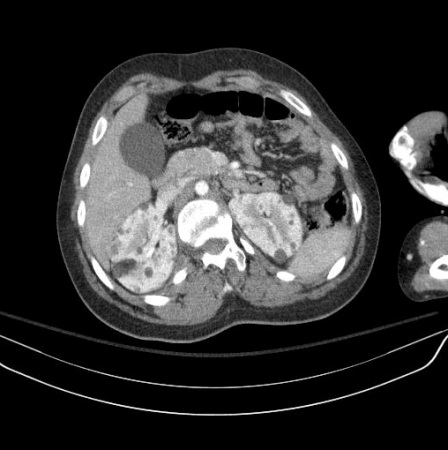

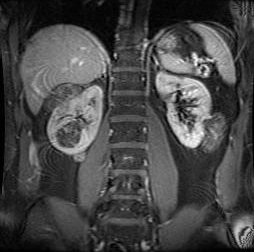

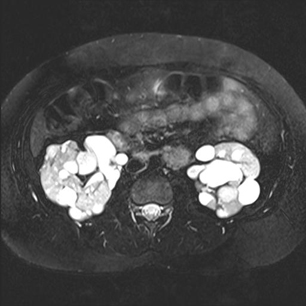

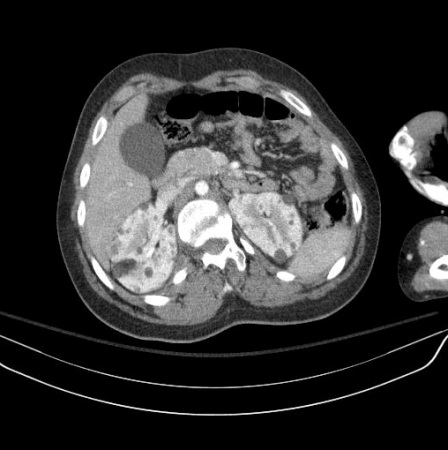

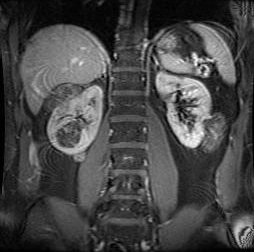

Renal angiomyolipoma(s)[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Multiple renal angiomyolipomas on axial CTCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Multiple renal angiomyolipomas on coronal T1 MRICourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Multiple renal angiomyolipomas on coronal T1 MRICourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

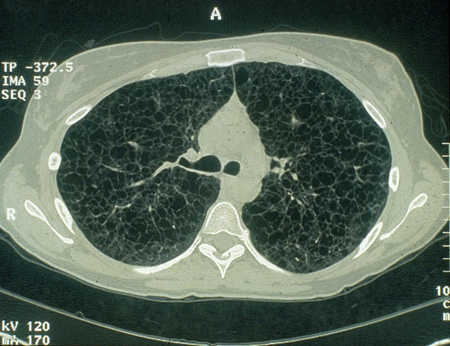

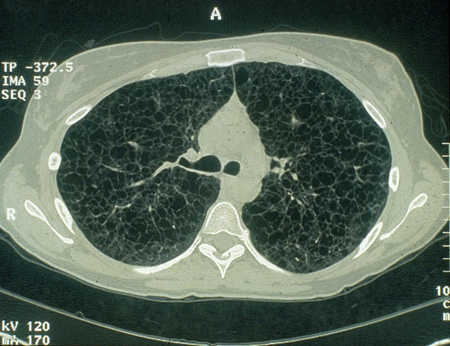

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis of the lung[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cystic lesions in lymphangioleiomyomatosis of the lung (LAM) on axial CTCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

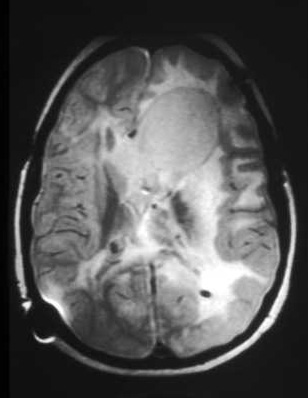

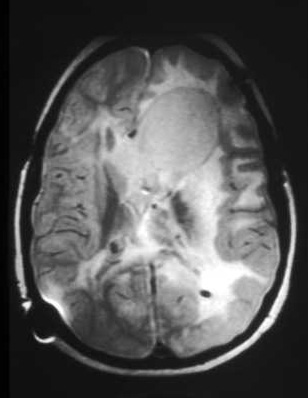

Cerebral subependymal calcified nodules or giant cell astrocytoma(s)[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Subependymal calcified nodules on CTCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (A-axial T2)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

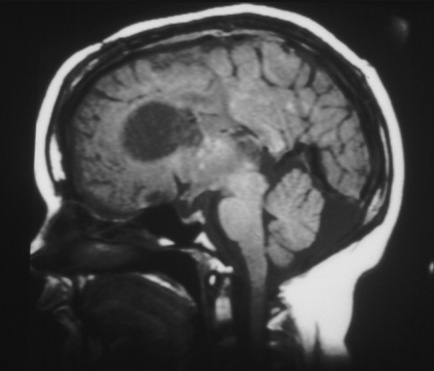

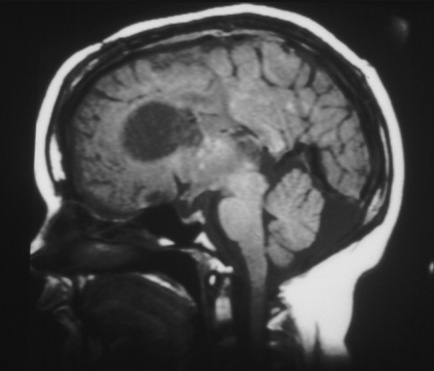

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (A-axial T2)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (B-sagittal T1)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (B-sagittal T1)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

Facial and/or ungual and periungual fibromas[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Facial angiofibromasCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ungual fibromaCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ungual fibromaCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

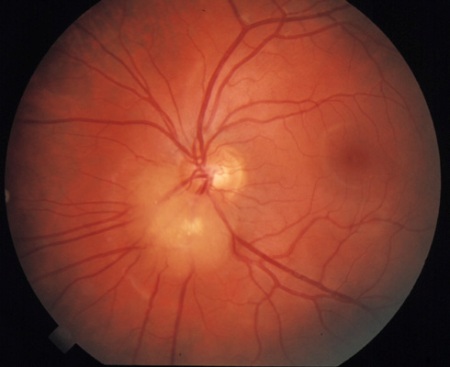

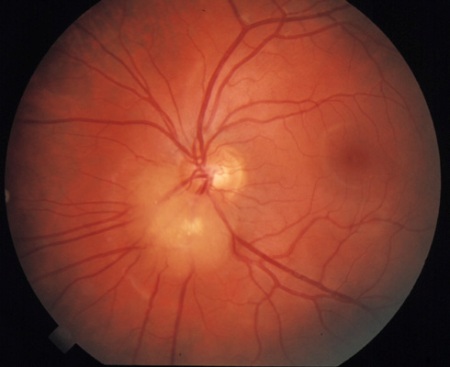

Retinal hamartoma(s)[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Retinal hamartomaCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

Shagreen patch(es) (connective tissue nevus)[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hypomelanotic macules and shagreen patchCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

Numerous dental enamel pits

Multiple hamartomatous intestinal polyps

Cognitive impairment

Forehead plaque(s)[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Forehead plaqueCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

Behavioural problems.

Examination

To make a definitive diagnosis, a careful physical examination should be performed to determine whether any additional major diagnostic findings are present, including:[18]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Gomez M, Sampson J, Whittemore V, eds. The tuberous sclerosis complex. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999.[3]Hyman MH, Whittemore VH. National Institutes of Health consensus conference: tuberous sclerosis complex. Arch Neurol. 2000 May;57(5):662-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10815131?tool=bestpractice.com

Detailed clinical dermatological inspection/examination for hypomelanotic macules, angiofibromas, and shagreen patches. A Wood's lamp (black or ultraviolet light) is helpful for detecting hypomelanotic macules not otherwise visible.

Detailed inspection for ungual fibromas and dental pitting.

Complete ophthalmological evaluation, including dilated fundoscopy, to assess for retinal findings (astrocytic hamartoma and achromic patch) and visual field deficits.

Genetic testing

Genetic testing is used to establish a diagnosis if the clinical criteria are unclear, and for family planning purposes for parents who have an affected child. Identification of a pathogenic variant in the TSC1 or TSC2 gene is sufficient for diagnosis or prediction of TSC irrespective of clinical findings.[18]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Caban C, Khan N, Hasbani DM, et al. Genetics of tuberous sclerosis complex: implications for clinical practice. Appl Clin Genet. 2016 Dec 21;10:1-8.

https://www.doi.org/10.2147/TACG.S90262

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28053551?tool=bestpractice.com

Blood testing for specific TSC gene mutations is definitive in around 75% to 90% of people with TSC when both genetic loci (TSC1 and TSC2) are examined.[18]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Caban C, Khan N, Hasbani DM, et al. Genetics of tuberous sclerosis complex: implications for clinical practice. Appl Clin Genet. 2016 Dec 21;10:1-8.

https://www.doi.org/10.2147/TACG.S90262

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28053551?tool=bestpractice.com

Genotyping may also be carried out by analysis of a buccal swab, saliva, or tissue samples. In around 10% to 15% of patients with TSC, a pathogenic TSC1 or TSC2 mutation cannot be detected by conventional testing methods.[18]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Caban C, Khan N, Hasbani DM, et al. Genetics of tuberous sclerosis complex: implications for clinical practice. Appl Clin Genet. 2016 Dec 21;10:1-8.

https://www.doi.org/10.2147/TACG.S90262

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28053551?tool=bestpractice.com

[13]Tyburczy ME, Dies KA, Glass J, et al. Mosaic and intronic mutations in TSC1/TSC2 explain the majority of TSC patients with no mutation identified by conventional testing. PLoS Genet. 2015 Nov;11(11):e1005637.

https://journals.plos.org/plosgenetics/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgen.1005637

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26540169?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://academic.oup.com/qjmed/article/112/3/171/5104881

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

Conventional genetic testing cannot identify the presence of gonadal mosaicism.

Further investigations

Brain and abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be performed to check for brain and renal lesions. MRI detects more abnormalities than computed tomography (CT) or ultrasound, and is the preferred imaging modality.[18]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

Contrast agents should be avoided for brain MRI unless there is a growing lesion or clinical suspicion of subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA). CT may be used if MRI is contraindicated or unavailable.[18]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

Comprehensive assessment of TSC-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) should be carried out at diagnosis using a validated screening tool such as the TAND checklist.[18]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]de Vries PJ, Whittemore VH, Leclezio L, et al. Tuberous sclerosis associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) and the TAND Checklist. Pediatr Neurol. 2015 Jan;52(1):25-35.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.10.004

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25532776?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]Leclezio L, Jansen A, Whittemore VH, et al. Pilot validation of the tuberous sclerosis-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) checklist. Pediatr Neurol. 2015 Jan;52(1):16-24.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.10.006

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25499093?tool=bestpractice.com

TAND checklist

Opens in new window

Routine electroencephalogram (EEG) should be obtained for all children diagnosed with TSC, to include both asleep and awake phases, to detect potential seizure activity. An abnormal EEG should be followed up with an 8- to 24-hour video-EEG assessment, especially if features of TAND are present.[18]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

A high-resolution chest CT should be performed for all women aged 18 years or older diagnosed with TSC, to evaluate for lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). Baseline pulmonary function tests and 6-minute walk test should be carried out in patients with evidence of lung disease consistent with LAM on the screening CT.[18]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://academic.oup.com/qjmed/article/112/3/171/5104881

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

Age-appropriate cardiac evaluation is carried out at time of diagnosis. Children, especially those younger than 3 years, should have echocardiography and electrocardiography (ECG) to check for rhabdomyomas and arrhythmia. Adults do not require routine echocardiography unless they have cardiac symptoms or a concerning medical history, but a baseline ECG is recommended.[18]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://academic.oup.com/qjmed/article/112/3/171/5104881

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

Blood pressure and glomerular filtration rate should be measured for all patients at diagnosis, to check for secondary hypertension and impaired renal function, respectively.[18]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

Other investigations (e.g., skeletal x-ray, colonoscopy, organ biopsy) are only performed for specific indications.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Multiple renal angiomyolipomas on coronal T1 MRICourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Multiple renal angiomyolipomas on coronal T1 MRICourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (A-axial T2)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (A-axial T2)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (B-sagittal T1)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (B-sagittal T1)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ungual fibromaCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ungual fibromaCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].