The prevention of RhD sensitisation in Rh-negative mothers carrying an Rh-positive fetus is the primary management objective. It involves immunoprophylaxis via the administration of anti-D immunoglobulin (also known as Rho(D) immune globulin in some countries) to at-risk women.

If sensitisation does occur, the window for primary prevention is effectively closed and Rh immunoprophylaxis is no longer appropriate. Actions then involve fetal and maternal surveillance for, and management of, fetal anaemia or hydrops.

Prevention of RhD sensitisation

Immunoprophylaxis with anti-D immunoglobulin is highly effective in preventing sensitisation of Rh-negative mothers carrying an Rh-positive fetus.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[26]Urbaniak SJ, Greiss MA. RhD haemolytic disease of the fetus and the newborn. Blood Rev. 2000 Mar;14(1):44-61.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10805260?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

It has been instrumental in the dramatic reduction in death from Rh incompatibility. Anti-D immunoglobulin is a blood product containing a high titre of antibodies to Rh antigens of red blood cells. Its precise mechanism of action is unknown, but it may work by neutralising Rh-positive fetal red blood cells in the maternal blood, thus reducing the risk of sensitisation. Administration is efficacious by either the intramuscular or intravenous route.[47]Okwundu CI, Afolabi BB. Intramuscular versus intravenous anti-D for preventing Rhesus alloimmunization during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jan 31;(1):CD007885.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD007885.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23440818?tool=bestpractice.com

Anti-Rh antibodies persist for more than 3 months after one dose.

A prerequisite for immunoprophylaxis is knowledge of the maternal rhesus status.[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

All pregnant women should be tested at the time of the first antenatal visit for RhD type, and screened for the presence of anti-D antibodies, to identify unsensitised RhD-negative patients who are potential candidates for immunoprophylaxis.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

Anti-D immunoglobulin is not given to an RhD-negative mother who is already sensitised to the RhD antigen.

Eligible candidates should receive routine ante- and postnatal administration of anti-D immunoglobulin, as described below. In addition, the risk of sensitisation can be reduced by administering anti-D immunoglobulin to women in situations in which fetomaternal haemorrhage (FMH) is likely, such as miscarriage, chorionic villus sampling, and amniocentesis.[7]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Routine antenatal anti-D prophylaxis for women who are rhesus D negative. Aug 2008 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA156

Multiple clinical guidelines describing RhD sensitisation prevention strategies have been published, including those from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics/International Confederation of Midwives.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

Routine postnatal administration of anti-D immunoglobulin

RhD sensitisation occurs in approximately 16% of pregnancies among RhD-negative women.[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

Postnatal administration of anti-D immunoglobulin reduces this risk to approximately 1.5%, and is the most effective intervention to prevent Rh incompatibility in subsequent pregnancies.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

Following birth, newborns from RhD-negative women should have their Rh factor determined from umbilical-cord blood.[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

If the infant is confirmed to be RhD-positive, all RhD-negative women who are not known to be sensitised should receive anti-D immunoglobulin (intravenously or intramuscularly) within 72 hours of delivery.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

Guidelines vary on the dose of anti-D immunoglobulin that should be administered, and can depend on the size of the FMH, the brand of anti-D immunoglobulin used, and affordability.[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

A prophylactic dose of 1500 IU (equivalent to 300 micrograms) of anti-D immunoglobulin is commonly given in high-income countries and can prevent RhD sensitisation after exposure to up to 30 mL of RhD-positive fetal whole blood or 15 mL of fetal red cells.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]Pollack W, Ascari WQ, Kochesky RJ, et al. Studies on Rh prophylaxis. 1. Relationship between doses of anti-Rh and size of antigenic stimulus. Transfusion. 1971 Nov-Dec;11(6):333-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5002765?tool=bestpractice.com

On rare occasions, delivery-associated FMH may be greater than 30 mL. Circumstances such as traumatic deliveries, caesarean sections, manual removal of the placenta, delivery of twins, and unexplained hydrops fetalis are more likely to be associated with a large FMH. Accordingly, several guidelines, including those from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and from the British Society for Haematology, recommend that RhD-negative women who give birth to RhD-positive infants should undergo additional testing to assess the volume of FMH and guide the amount of anti-D immunoglobulin required to prevent sensitisation.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Qureshi H, Massey E, Kirwan D, et al. BCSH guideline for the use of anti-D immunoglobulin for the prevention of haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Transfus Med. 2014 Feb;24(1):8-20.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tme.12091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25121158?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Fung MK, Grossman BJ, Hillyer CD, et al, eds. Technical manual. 18th ed. Bethesda (MD): American Association of Blood Banks; 2014. However, at no time should anti-D immunoglobulin treatment be delayed pending the results of quantitative FMH testing.[50]National Blood Authority. Prophylactic use of Rh D immunoglobulin in pregnancy care. 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.blood.gov.au/anti-d-0

If anti-D immunoglobulin is not given within 72 hours of delivery, it should be given as soon as the need is recognised, for up to 28 days after delivery.[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

Routine antenatal administration of anti-D immunoglobulin

Building on the efficacy of postnatal anti-D immunoglobulin administration, the risk of RhD sensitisation in Rh-negative women carrying an Rh-positive baby has been shown to be further reduced (to approximately 0.5%) by the introduction of routine antenatal administration.[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

[51]McBain RD, Crowther CA, Middleton P. Anti-D administration in pregnancy for preventing Rhesus alloimmunisation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Sep 3;(9):CD000020.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD000020.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26334436?tool=bestpractice.com

Routine antenatal antibody screening should be obtained at 28 weeks of gestation before administration of anti-D immunoglobulin (to identify women who have become sensitised before 28 weeks of gestation).[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Qureshi H, Massey E, Kirwan D, et al. BCSH guideline for the use of anti-D immunoglobulin for the prevention of haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Transfus Med. 2014 Feb;24(1):8-20.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tme.12091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25121158?tool=bestpractice.com

[52]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The management of women with red cell antibodies during pregnancy: green-top guideline no 65. May 2014 [internet publication].

https://www.rcog.org.uk/media/oykp1rtg/rbc_gtg65.pdf

If anti-D antibodies are identified, it should be determined whether this presence is immune-mediated or passive (e.g., as a result of previous anti-D immunoglobulin treatment). If RhD antibodies are passive, then the woman should continue to be offered prophylaxis with anti-D immunoglobulin; however, if they are present because of sensitisation, prophylaxis is not beneficial, and management should proceed in accordance with protocols for RhD-sensitised pregnancies.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

Prophylactic antenatal anti-D immunoglobulin should be offered to unsensitised RhD-negative women, whether the fetal blood type is unknown or known to be Rh-positive.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that a single dose be offered at 28 weeks of gestation, while other guidelines recommend either a single dose at around 28 weeks, or two doses at around 28 and 34 weeks of gestation.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Qureshi H, Massey E, Kirwan D, et al. BCSH guideline for the use of anti-D immunoglobulin for the prevention of haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Transfus Med. 2014 Feb;24(1):8-20.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tme.12091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25121158?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

Non-invasive estimation of fetal Rh status is now possible via the analysis of cell-free DNA in maternal plasma, and this method may be acceptable for sensitised patients who refuse amniocentesis.[35]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Clinical practice update: paternal and fetal genotyping in the management of alloimmunization in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. June 4 2024;144(2):e47-9.

https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/abstract/2024/08000/acog_clinical_practice_update__paternal_and_fetal.34.aspx

Some countries recommend employing this technique in the first trimester, to allow targeted antenatal RhD immunoprophylaxis (i.e., only where the fetus is RhD-positive); however, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not recommend the routine use of this approach on the grounds of cost-effectiveness.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

When paternity is certain, rhesus testing of the baby’s father may be offered as a means of determining fetal RhD status.[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

[35]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Clinical practice update: paternal and fetal genotyping in the management of alloimmunization in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. June 4 2024;144(2):e47-9.

https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/abstract/2024/08000/acog_clinical_practice_update__paternal_and_fetal.34.aspx

Routine antenatal anti-D immunoglobulin prophylaxis should be administered regardless of, and in addition to, any anti-D immunoglobulin that may have been given for a potentially sensitising event (see below).[36]Qureshi H, Massey E, Kirwan D, et al. BCSH guideline for the use of anti-D immunoglobulin for the prevention of haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Transfus Med. 2014 Feb;24(1):8-20.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tme.12091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25121158?tool=bestpractice.com

In the past, it has been recommended that a second dose of anti-D immunoglobulin should be administered to women who have not given birth at 40 weeks; however, the current guidelines suggest that this is generally not required, provided that the antenatal injection was given no earlier than 28 weeks' gestation.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

Administration of anti-D immunoglobulin following potentially sensitising events

In RhD-negative, previously unsensitised women, a variety of events associated with potential placental trauma or disruption of the fetomaternal interface can lead to sensitising FMH during pregnancy. Anti-D immunoglobulin can help minimise the risk of such sensitisation, and if indicated, should be administered as soon as possible after the event, ideally within 72 hours.[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Qureshi H, Massey E, Kirwan D, et al. BCSH guideline for the use of anti-D immunoglobulin for the prevention of haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Transfus Med. 2014 Feb;24(1):8-20.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tme.12091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25121158?tool=bestpractice.com

If anti-D immunoglobulin is not given within 72 hours, it should be given as soon as the need is recognised, for up to 28 days after the potentially sensitising event.[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

For sensitising events occurring after 20 weeks of pregnancy, the magnitude of FMH should be assessed, and further doses of anti-D immunoglobulin administered if required.[36]Qureshi H, Massey E, Kirwan D, et al. BCSH guideline for the use of anti-D immunoglobulin for the prevention of haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Transfus Med. 2014 Feb;24(1):8-20.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tme.12091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25121158?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]National Blood Authority. Prophylactic use of Rh D immunoglobulin in pregnancy care. 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.blood.gov.au/anti-d-0

Miscarriage/abortion and intrauterine fetal death

Guidelines for the administration of anti-D immunoglobulin following miscarriage/abortion vary and local protocols should be followed.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Qureshi H, Massey E, Kirwan D, et al. BCSH guideline for the use of anti-D immunoglobulin for the prevention of haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Transfus Med. 2014 Feb;24(1):8-20.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tme.12091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25121158?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]National Blood Authority. Prophylactic use of Rh D immunoglobulin in pregnancy care. 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.blood.gov.au/anti-d-0

[53]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis and initial management. Nov 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng126

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists states that in the case of spontaneous first-trimester miscarriage or abortion in RhD-negative women, the risk of sensitisation is very low so routine Rh testing and Rh immunoprophylaxis is not recommended. However, Rh testing and administration of anti-D immunoglobulin may be considered on an individual basis, according to patient preferences.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[27]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG clinical practice update: Rh D immune globulin administration after abortion or pregnancy loss at less than 12 weeks of gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2024 Dec 1;144(6):e140-3.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39255498?tool=bestpractice.com

It recommends that anti-D immunoglobulin should be given to unsensitised RhD-negative women who have a pregnancy termination (either medical or surgical); or who experience fetal death in the second or third trimester.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[27]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG clinical practice update: Rh D immune globulin administration after abortion or pregnancy loss at less than 12 weeks of gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2024 Dec 1;144(6):e140-3.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39255498?tool=bestpractice.com

Guidelines from the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics/International Confederation of Midwives note that because an intrauterine fetal death may have been caused by a large FMH, it may be useful to perform a Kleihauer–Betke test, to determine the size of the haemorrhage, and thus the dose of anti-D immunoglobulin needed.[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

Ectopic pregnancy

Several guidelines recommend the administration of anti-D immunoglobulin for all cases of ectopic pregnancy in unsensitised RhD-negative women.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

However, in the UK, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend that anti-D immunoglobulin should only be administered to Rh-negative women who have surgical management of an ectopic pregnancy (and not those who have solely medical management).[53]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis and initial management. Nov 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng126

Molar pregnancy

In a complete molar pregnancy, sensitisation to RhD should not occur, due to the absence of fetal organ development. However, the situation is different in a partial molar pregnancy. Because differentiating between the forms of molar pregnancy may be difficult, it is generally advised to administer anti-D immunoglobulin to all unsensitised RhD-negative women with a molar pregnancy.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

Invasive procedures (e.g., chorionic villus sampling, amniocentesis)

Most countries recommend administration of anti-D immunoglobulin following invasive diagnostic procedures, such as chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis, in unsensitised RhD-negative women when the fetuses could be RhD-positive.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Qureshi H, Massey E, Kirwan D, et al. BCSH guideline for the use of anti-D immunoglobulin for the prevention of haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Transfus Med. 2014 Feb;24(1):8-20.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tme.12091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25121158?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

Bleeding and abdominal trauma in pregnancy

Anti-D immunoglobulin is recommended for RhD-negative women who experience antenatal haemorrhage after 20 weeks of gestation; some guidelines also suggest anti-D immunoglobulin should be considered in certain cases of bleeding earlier in gestation.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Qureshi H, Massey E, Kirwan D, et al. BCSH guideline for the use of anti-D immunoglobulin for the prevention of haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Transfus Med. 2014 Feb;24(1):8-20.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tme.12091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25121158?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

Anti-D immunoglobulin should be administered to RhD-negative women who have experienced abdominal trauma.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Qureshi H, Massey E, Kirwan D, et al. BCSH guideline for the use of anti-D immunoglobulin for the prevention of haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Transfus Med. 2014 Feb;24(1):8-20.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tme.12091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25121158?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Visser GHA, Thommesen T, Di Renzo GC, et al. FIGO/ICM guidelines for preventing Rhesus disease: a call to action. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;152(2):144-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7898700

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128246?tool=bestpractice.com

Quantitative testing for FMH may be considered following events potentially associated with placental trauma and disruption of the fetomaternal interface (e.g., placental abruption, blunt trauma to the abdomen, cordocentesis, placenta praevia with bleeding).[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

There is a substantial risk of FMH over 30 mL with such events.[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

External cephalic version in breech presentation

Some guidelines recommend administration of anti-D immunoglobulin for unsensitised RhD-negative patients following external cephalic version.[23]American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 181: prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Aug;130(2):e57-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28742673?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Qureshi H, Massey E, Kirwan D, et al. BCSH guideline for the use of anti-D immunoglobulin for the prevention of haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Transfus Med. 2014 Feb;24(1):8-20.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tme.12091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25121158?tool=bestpractice.com

Quantitative testing for FMH may also be considered.[29]Fung KFK, Eason E. No. 133: prevention of Rh alloimmunization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Jan;40(1):e1-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29274715?tool=bestpractice.com

Verbal or written consent must be obtained prior to administration of anti-D immunoglobulin.

Management following RhD sensitisation

If antibody screening identifies anti-D antibodies in an RhD-negative pregnant woman, and assessments conclude that their presence is active, not passive, the patient should be considered sensitised, and specialist obstetric advice should be sought.[50]National Blood Authority. Prophylactic use of Rh D immunoglobulin in pregnancy care. 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.blood.gov.au/anti-d-0

Rh immunoprophylaxis is no longer given.[34]American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 192: management of alloimmunization during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Mar;131(3):e82-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29470342?tool=bestpractice.com

Fortunately, initial sensitisation in a first affected pregnancy is often mild.

The initial management of an RhD-sensitised pregnancy involves the determination of the paternal rhesus status. If paternity is certain, and the father is RhD-negative, no further assessment/intervention is necessary. All children from a homozygous RhD-positive father, and 50% from a heterozygous RhD-positive father, will be RhD-positive.[34]American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 192: management of alloimmunization during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Mar;131(3):e82-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29470342?tool=bestpractice.com

In the case of a heterozygous RhD-positive, or unknown, paternal genotype, the fetal antigen type should be assessed (by amniocentesis or non-invasive analysis of maternal blood).[34]American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 192: management of alloimmunization during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Mar;131(3):e82-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29470342?tool=bestpractice.com

In the case of an RhD-positive fetus, management involves fetal and maternal surveillance for signs of fetal anaemia and hydrops.

Quantitation of maternal antibody titre is performed serially to document worsening disease and identify the need for additional fetal testing and/or treatment. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists states that a critical titre (titre associated with a significant risk for severe haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn, and hydrops) is considered to be between 1:8 and 1:32 in most centres.[34]American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 192: management of alloimmunization during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Mar;131(3):e82-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29470342?tool=bestpractice.com

If the initial antibody titre is 1:8 or less, the patient may be monitored with titre assessment every 4 weeks.[34]American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 192: management of alloimmunization during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Mar;131(3):e82-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29470342?tool=bestpractice.com

However, serial titres are not adequate for monitoring fetal status when the mother has had a previously affected fetus or neonate.[34]American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 192: management of alloimmunization during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Mar;131(3):e82-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29470342?tool=bestpractice.com

In the UK, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommends anti-D antibodies should be measured every 4 weeks up to 28 weeks of gestation and then every 2 weeks until delivery, and referral to a fetal medicine specialist should occur if there are rising antibody levels, if the level reaches the specific threshold of >4 IU/mL, or if ultrasound features are suggestive of fetal anaemia.[52]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The management of women with red cell antibodies during pregnancy: green-top guideline no 65. May 2014 [internet publication].

https://www.rcog.org.uk/media/oykp1rtg/rbc_gtg65.pdf

In a centre with trained personnel and when the fetus is at an appropriate gestational age, Doppler measurement of peak systolic velocity in the fetal middle cerebral artery is an appropriate non-invasive means to monitor pregnancies complicated by RhD sensitisation.[34]American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 192: management of alloimmunization during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Mar;131(3):e82-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29470342?tool=bestpractice.com

Fetal ultrasound assessment is also employed.

Most cases of rhesus sensitisation causing serious haemolytic disease in the fetus are the result of incompatibility with respect to the D antigen.[34]American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 192: management of alloimmunization during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Mar;131(3):e82-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29470342?tool=bestpractice.com

However, over 30 antigenic variants have been identified, and care of patients with sensitisation to non-RhD antigens that are known to cause haemolytic disease should be the same as that for patients with D sensitisation.[34]American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 192: management of alloimmunization during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Mar;131(3):e82-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29470342?tool=bestpractice.com

A possible exception is Kell sensitisation.[34]American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 192: management of alloimmunization during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Mar;131(3):e82-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29470342?tool=bestpractice.com

Fetal therapy

The goal of fetal therapy is to correct severe anaemia, ameliorate tissue hypoxia, prevent (or reverse) fetal hydrops, and avoid fetal death.

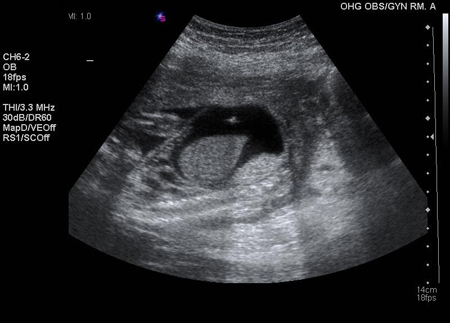

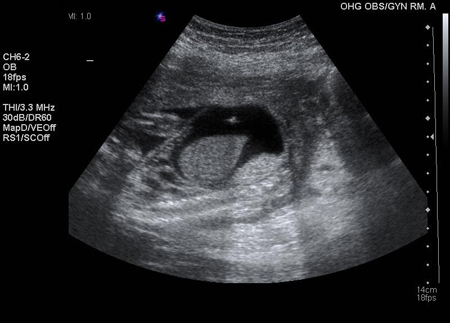

If fetal blood is Rh-negative, or if middle cerebral artery blood flow or amniotic bilirubin levels remain normal in an Rh-positive fetus, the pregnancy can continue to term untreated. If fetal blood is Rh-positive or of unknown Rh status, and middle cerebral artery flow or amniotic bilirubin levels are elevated, suggesting fetal anaemia, the fetus can be given intravascular intrauterine blood transfusions by a specialist at an institution equipped to care for high-risk pregnancies. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intraperitoneal transfusion; the echogenic needle tip is visualised in the pocket of ascitesThe Ottawa Hospital; used with consent of the patient [Citation ends].

Neonatal therapy

Neonates with erythroblastosis are immediately evaluated by a paediatrician to determine the need for exchange transfusion, phototherapy, or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). IVIG is used in some clinical practice as it has been shown to reduce the need for exchange transfusion in neonates with proven haemolytic disease due to Rh and/or ABO incompatibility and to decrease the duration of hospitalisation and phototherapy.[54]Li MJ, Chen CH, Wu Q, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin G for hemolytic disease of the newborn: a systematic review [in Chinese]. Chin J Evid Based Med. 2010;10:1199-204.

http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-ZZXZ201010016.htm

[55]Huizing K, Røislien J, Hansen T. Intravenous immunoglobulin reduces the need for exchange transfusion in Rhesus and ABO incompatibility. Acta Paediatr. 2008 Oct;97(10):1362-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18616629?tool=bestpractice.com

However, there is an overall lack of evidence to support its use for the treatment of alloimmune haemolytic disease.[56]Smits-Wintjens VE, Walther FJ, Rath ME, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin in neonates with rhesus hemolytic disease: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2011 Apr;127(4):680-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21422084?tool=bestpractice.com

[57]Zwiers C, Scheffer-Rath ME, Lopriore E, et al. Immunoglobulin for alloimmune hemolytic disease in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Mar 18;(3):CD003313.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003313.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29551014?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

What are the benefits and harms of immunoglobulin for neonates with alloimmune hemolytic disease/jaundice?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.2095/fullShow me the answer[Evidence C]4509cc75-dd20-41da-9a0e-ba338e3b2c4eccaCWhat are the benefits and harms of immunoglobulin for neonates with alloimmune haemolytic disease/jaundice?

]

What are the benefits and harms of immunoglobulin for neonates with alloimmune hemolytic disease/jaundice?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.2095/fullShow me the answer[Evidence C]4509cc75-dd20-41da-9a0e-ba338e3b2c4eccaCWhat are the benefits and harms of immunoglobulin for neonates with alloimmune haemolytic disease/jaundice?

]

[Evidence C]

]

[Evidence C]