Approach

In Rh-negative pregnant women, where Rh paternal phenotype is positive or unknown, the possibility of them becoming alloimmunised and producing red cell antibodies should be considered. Laboratory testing for the presence of red cell antibodies is confirmatory.

Clinical evaluation

All RhD-negative pregnant women (where the fetus has an Rh-positive father) are at potential risk for alloimmunisation and erythroblastosis. Risk factors for maternal sensitisation to RhD antigen include: history of an Rh-positive fetus to an Rh-negative mother; invasive fetal procedures; fetomaternal haemorrhage; placental trauma; spontaneous, threatened, or induced abortion; omission (or inadequate dosing) of appropriate Rh immunoprophylaxis following a potentially immunising obstetric event in a previous or current pregnancy; and multiparity.

Accurate maternal history taking is an important step in evaluating potential risk of sensitisation or fetal anaemia in a current pregnancy. Inquiry should begin with questioning about previous pregnancies, paternal phenotype (if known), history of blood transfusion, administration of Rh immunoprophylaxis, and obstetric and neonatal outcome of all pregnancies.

Although the primary maternal immune response to sensitisation by the D antigen is usually weak, it may be greatly enhanced when a secondary immune response is generated by antigenic challenge in a subsequent pregnancy. Hence, the risk for fetal anaemia and immune fetal hydrops (abnormal accumulation of fluid in 2 or more fetal compartments) increases with increasing parity.[2][26][31] When hydrops has occurred in a previous pregnancy, it is likely to occur again, and at an earlier gestational age. Once hydrops or a stillbirth has occurred due to anti-D antibodies from Rh incompatibility, the estimated chance of intrauterine death of a subsequent RhD-positive fetus is 90% if untreated.[32]

Laboratory investigations

Blood type and antibody screening

At the first antenatal visit, all women are screened for ABO blood group, Rh type, and the presence of red blood cell (RBC) antibodies.[23][33] Repeated RhD-antibody testing for all unsensitised RhD-negative women is also recommended at 24-28 weeks’ gestation, unless the biological father is known to be RhD-negative.[33] A positive red blood cell antibody screen in an Rh-negative mother demands further investigation, including identification of the antibody and measurement of the titre.

An identifiable Rh antibody screen in an Rh-negative mother should prompt paternal phenotyping and genotyping (if paternity is certain). A father with Rh-positive blood may be homozygous or heterozygous for the D antigen. If the latter, the risk of transmission of the RhD gene (and hence the risk of Rh incompatibility) to the fetus is 50%, compared with 100% if he is homozygous. In the case of a heterozygous RhD-positive, or unknown, paternal genotype, fetal Rh type is determined by genetic testing of amniotic fluid cells or it can be estimated using cell-free fetal DNA in the maternal circulation, which may be helpful in mothers who refuse amniocentesis.[34][35]

In sensitised patients the maternal serum antibody titre is a guide to disease severity. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists states that a critical titre (titre associated with a significant risk for severe haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn, and hydrops) is considered to be between 1:8 and 1:32 in most centres.[34] If the initial antibody titre is 1:8 or less, the patient may be monitored with titre assessment every 4 weeks.[34] However, serial titres are not adequate for monitoring fetal status when the mother has had a previously affected fetus or neonate.[34]

Assessing fetomaternal haemorrhage

A rosette test can be used to rule out significant fetomaternal haemorrhage. If results are positive, a Kleihauer-Betke (acid elution) test or flow cytometry can measure the amount of fetal blood in the maternal circulation. Such assessments may be carried out in a variety of circumstances, including in unsensitised Rh-negative mothers carrying an RhD-positive fetus (or when fetal RhD status is unknown) following birth; sensitising events occurring after 20 weeks’ gestation; or events potentially associated with placental trauma and disruption of the fetomaternal interface (e.g., placental abruption, blunt trauma to the abdomen, cordocentesis, placenta praevia with bleeding).[23][29][36]

Fetal ultrasound and blood sampling

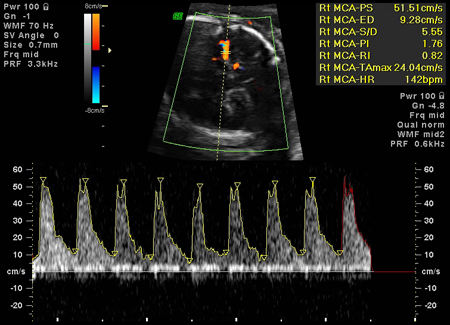

Fetal anaemia due to Rh incompatibility can be diagnosed by measuring peak systolic velocity in the middle cerebral artery (MCA). The prediction of moderate to severe anaemia by Doppler ultrasound has a sensitivity of 100% and false-positive rate of 12%.[31][37] Elevated blood flow velocity for gestational age should prompt percutaneous umbilical blood sampling (if anaemia is strongly suspected).

Fetal blood sampling through umbilical cord venepuncture (cordocentesis) or the intrahepatic vein allows direct measurement of the fetal haemoglobin and haematocrit.

Definitive information on the severity of anaemia will direct appropriate and life-saving fetal therapy through intrauterine fetal transfusion.[38]

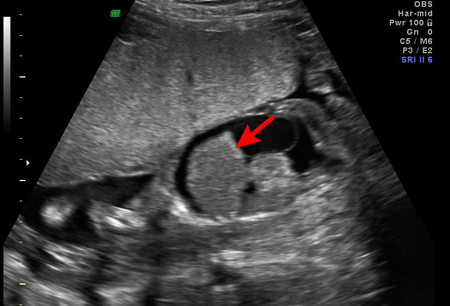

Ultrasound examination of the fetus at risk for Rh incompatibility may reveal subcutaneous oedema, ascites, pleural effusion, or pericardial effusion, all of which are consistent with severe fetal anaemia in an affected fetus.[39]

Non-invasive screening for fetal anaemia with Doppler ultrasound has supplanted serial amniocentesis for spectrophotometry in developed countries, but may not be available in all other regions. Where used, spectral analysis of amniotic fluid at optical density 450 nanometres (AOD450) measures the level of bilirubin as an indirect indicator of fetal haemolysis. Liley proposed a management scheme involving three zones based on gestational age between 27 and 42 weeks. When used to monitor fetal disease, serial procedures are undertaken at 10-day to 2-week intervals and continued until delivery.[16] Queenan and co-workers proposed a modified AOD450 curve between 14 weeks and 40 weeks. The Queenan curve has shown better predictive value than the Liley curve in severe anaemia.[30][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Increased velocity in the middle cerebral artery consistent with severe fetal anaemiaThe Ottawa Hospital; used with consent of the patient [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fetal hydrops, with ascites and hepatomegaly (arrow) diagnosed on antenatal ultrasoundThe Ottawa Hospital; used with consent of the patient [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fetal hydrops, with ascites and hepatomegaly (arrow) diagnosed on antenatal ultrasoundThe Ottawa Hospital; used with consent of the patient [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer