Approach

The clinical presentation of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection depends on the immune status of the patient. Immunocompetent individuals often do not show clinical symptoms. However, immunocompromised individuals have fever, bone marrow suppression, and end-organ diseases. Full blood count, serum creatinine, and liver function tests (LFTs) are recommended for all patients presenting with clinical features of CMV. Diagnostic testing for CMV confirmation should be performed in each suspected case, and the method of testing depends on immune status.

Laboratory evaluation of CMV

In immunocompetent patients, primary CMV infection is diagnosed using serology, to detect CMV-specific IgM. Low avidity of CMV antibodies can confirm the diagnosis of recent CMV infection. Serology in the transplant setting is useful to establish the risk for CMV disease, but not for the diagnosis of acute CMV infection.

In immunocompromised hosts, the diagnosis of CMV disease is confirmed by the demonstration or detection of the virus in blood and tissue specimens.[33] Viral culture of blood, respiratory secretions, vitreous fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, and tissue specimens may be used to demonstrate CMV infection. Conventional tube culture takes several weeks before cytopathic effects can be demonstrated; hence, it is not useful in real-time clinical care. The shell vial assay (another type of viral culture technique) produces results within 48 hours, but viral culture generally has modest sensitivity and has been replaced by molecular assays in most settings.

Currently, the most rapid and sensitive molecular method for detecting CMV in these specimens is the use of quantitative nucleic acid testing (NAT) that detects and quantifies viral nucleic acid. Many physicians consider this a diagnostic method of choice. The assay is rapid, and its quantitative property allows for disease prognostication, and serves as a guide during treatment. However, results from various NAT assays have not been directly compared. A WHO standard for CMV quantitation has been developed and viral loads can now be reported in international units allowing for greater standardisation, although some data suggests that significant ongoing variability between laboratories may still exist.[34][35]

In some centres, detecting pp65 antigen (antigenaemia assay) in peripheral blood leukocytes is a rapid method for diagnosis.[36] The requirement for leukocytes in this assay limits its utility in people with leukopenia, such as haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients and those receiving cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents.[36] In addition, it is semi-quantitative and difficult to standardise across centres.[36] Antigenaemia assays are currently seldom used for the diagnosis of CMV infection.

Clinical presentation and investigation in people with normal immune function

Presenting features:

In healthy people, CMV infection is usually asymptomatic.

If symptomatic, the clinical manifestations of CMV infection may resemble infectious mononucleosis syndrome (fever, malaise, sore throat).

A maculopapular rash after administration of antibiotics may present.

Physical examination is often unremarkable except for the presence of lymphadenopathy. Splenomegaly is occasionally present.

FBC:

Atypical lymphocytosis, which may be the laboratory marker of viral infection such as CMV, in an immunocompetent patient.

LFTs:

Aminotransferases or alkaline phosphatase may be elevated.

Detection of CMV:

Every patient with suspected CMV infection should be tested to confirm the presence of CMV. While NAT assay provides rapid diagnosis, CMV serology (CMV IgM) is the most accessible test in the community setting and often sufficient for diagnosis in immunocompetent individuals

Clinical presentation and investigation in solid organ and haematopoietic stem cell transplant patients

Presenting features:

Fever in solid organ and haematopoietic stem cell transplant patients should be assessed as a possible manifestation of CMV disease. This is especially relevant in solid organ transplant recipients with certain risk factors such as being CMV-seronegative with a seropositive donor (CMV D+/R-), acute rejection, receipt of intense immunosuppressive drugs, or sepsis.[27] It is also relevant in the case of a CMV-seropositive allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipient at high risk because of severe T-cell depletion, or patients with graft-versus-host disease.[21] Many patients may also present with significant malaise in the absence of fever.

CMV may affect the gastrointestinal tract; vomiting (gastritis) and diarrhoea (colitis) can occur. Pneumonitis may present with cough and dyspnoea. Myocarditis, hepatitis, pancreatitis, nephritis, and encephalitis occur rarely. In contrast to patients with AIDS, CMV retinitis is not commonly observed in transplant recipients.[37]

Virtually any organ system may be affected by CMV.

FBC:

Often shows anaemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia.

LFT:

CMV hepatitis may manifest with elevated serum levels of alanine and aspartate aminotransferases. Elevated alkaline phosphatase levels often indicate accompanying hepatobiliary system involvement.[33]

Detection of CMV:

Quantitative NAT is preferred over pp65 antigenaemia and viral due to its higher sensitivity and faster results. CMV serology is not usually ordered in transplant patients for diagnosing acute CMV disease.[36] Specimens for NAT should be obtained from the presumptive site of disease.

Chest x-ray:

This should be performed in severely immunocompromised patients with pulmonary symptoms suggestive of CMV disease. In CMV pneumonitis, interstitial infiltrates may be observed, although nodules may occasionally occur.[38] If the diagnosis of lung involvement requires further radiological evaluation, a lung CT scan should be performed.[39] [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest CT scan of a lung transplant recipient with diffuse interstitial and parenchymal changes as a result of primary CMV pneumonitisFrom the collection of Dr Raymund Razonable; used with permission [Citation ends].

Endoscopy and colonoscopy:

These may be indicated in patients with signs of gastrointestinal involvement, and may demonstrate mucosal hyperaemia and ulcerations typical of CMV disease.[40] In clinical practice however, a presumptive diagnosis of gastrointestinal disease is often made based on detection of viraemia, accompanied with appropriate signs and symptoms. However, not all patients with CMV gastritis or colitis develop viraemia.[41]

Biopsy:

Patients with clinical illness suggestive of tissue-invasive CMV disease may have tissue specimens (liver, intestinal mucosa, lung) obtained by biopsy for the detection of CMV inclusion bodies.[36][42] Often, symptoms may mimic acute allograft rejection, and biopsy will help to differentiate these clinical entities.

Clinical presentation and investigation in patients with AIDS

Presenting features:

In patients with AIDS, the most common clinical manifestation of CMV disease is retinitis.[2] Colitis is the second most common manifestation.

Involvement of other organ systems may be manifested by headache (encephalitis), weakness, cough and dyspnoea (pneumonitis), vomiting (gastritis), diarrhoea, and other gastrointestinal symptoms (colitis).[2] Virtually any organ system may be affected by CMV.[43]

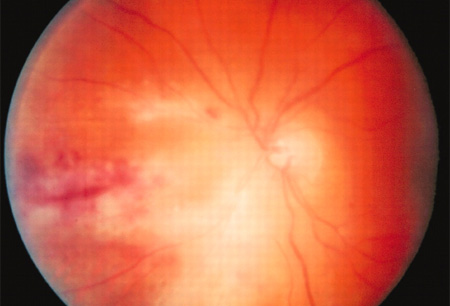

Fundoscopy: visual floaters are the most common complaint leading to medical evaluation, with severe cases leading to blindness within months of diagnosis. Fundoscopic examination is important to assess the retina in both asymptomatic and symptomatic patients suspected of having CMV retinitis. In the presence of CMV retinitis, fundoscopy will reveal areas of infarction, haemorrhage, peri-vascular sheathing, and retinal opacification.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fundoscopy (left eye) showing area of CMV retinitis inferonasally involving the vascular arcades and the optic disc, associated with vasculitis and flame haemorrhagesAdapted from BMJ Case Reports 2009, copyright © 2009 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends].

FBC:

May show anaemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia.

Detection of CMV:

NAT and pp65 antigen detection, as well as viral culture, may be used to detect CMV in blood, affected fluid, or tissue specimens.

CD4 count:

Clinically, the patient has severe immunosuppression, as indicated by CD4 T-cell count of <50 cells/microlitre.[2]

Chest x-ray:

This should be performed in any immunocompromised patient with pulmonary symptoms suggestive of CMV disease. May demonstrate interstitial infiltrates in the presence of CMV pneumonitis. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing diffuse pulmonary infiltrates in an immunocompromised patient with severe CMV pneumonitisFrom the collection of Dr Raymund Razonable; used with permission [Citation ends].

Biopsy:

In patients with clinical illness suggestive of tissue-invasive CMV disease, biopsy of tissue specimens (liver, intestinal mucosa, lung) is recommended.[2] CMV retinitis presents with classic fundoscopic findings and biopsy is not required. However, in atypical cases, CMV NAT of the vitreous fluid will confirm the diagnosis.

Clinical presentation and investigation in infants with congenital CMV infection

Antenatal diagnosis:

Congenital CMV infection should be suspected if there is symptomatic or asymptomatic maternal seroconversion during pregnancy, or if fetal abnormalities suggestive of CMV infection are detected on antenatal ultrasound.[10]

The diagnosis of maternal primary CMV infection in pregnancy is usually based on positive CMV-IgG in a pregnant woman who was previously seronegative, or on detection of specific IgM antibody associated with low IgG avidity.[30] In the absence of universal maternal screening, serological testing for CMV is indicated for women with influenza-like illness during pregnancy, following detection of sonographic findings suggestive of congenital CMV infection, or if requested by an asymptomatic mother. Similar clinical outcomes have been reported in newborns born to mothers with primary infection versus those born to mothers with non-primary infections.[44] As such, seronegative mothers at higher risk of exposure to CMV (e.g., healthcare and childcare workers, mothers with a child attending daycare) may be offered serological monitoring during pregnancy.[29]

Antenatal ultrasound features suggestive of congenital CMV infection include: intrauterine fetal growth restriction, enlargement of the cerebral ventricles, intracranial calcification, microcephaly, and increase or decrease in the volume of amniotic fluid. Enlargement of the liver, spleen, or heart, and hyperechogenicity of the bowel, may also be seen.[10] Serial ultrasound examinations should be performed every 2-4 weeks after a diagnosis of congenital CMV infection in order to detect sonographic abnormalities; these may aid in determining fetal prognosis, although the absence of sonographic findings does not guarantee a normal outcome.[29]

Amniocentesis or fetal blood sampling allow for testing of CMV starting from 21 weeks of gestation.[29][30] Fetal blood specimens and amniotic fluid are tested for CMV using NAT. IgM antibody measurement, pp65 antigenaemia, and viral culture are not commonly used.

Important factors to consider in antenatal diagnosis are: confirmation of primary CMV infection in the mother, attempting to establish the time at which the mother was infected, and to choose an appropriate time at which to acquire fetal samples. There is an increased risk of false-negative results if fetal sampling is performed too close to the onset of infection in the mother, usually before 21 weeks of gestation.[45] Mothers should be counselled about the risks of fetal transmission, risks associated with diagnostic procedures, and risks involved in fetal infection in order to make a decision on further testing, and how to continue with pregnancy.[10][30]

Presenting features at birth:

Around 85% to 90% of newborns with congenital CMV infection are asymptomatic at birth. The remaining 15% to 20% may present with microcephaly, hepatosplenomegaly, petechiae or purpura, or sensorineural hearing loss. Less commonly, clinical examination may reveal hypotonia or abnormal head lag.[46][47] Of the 10% to 15% of newborns with symptoms at birth, 40% to 60% will develop permanent and long-term neurodevelopmental abnormalities and sensorineural deafness.[10]

Tests at birth:

FBC: may show thrombocytopenia

LFTs: may be elevated.

Diagnosis of CMV in the neonate:

CMV can be detected by molecular assays of saliva and/or urine drawn within the first three weeks of life. Other diagnostic methods such as viral culture, pp65 antigen detection, and CMV serology are not performed routinely given the increased sensitivity of molecular assays. CMV can also be detected by molecular assays from central nervous system and blood samples.[46]

Routine testing for congenital CMV infection in the first 21 days of life is recommended for infants with vertically transmitted HIV. CMV testing is also recommended for all infants exposed to HIV in utero, since their HIV status will be indeterminate during the first three weeks of life when congenital CMV infection can be diagnosed. Data indicate that the prevalence of congenital CMV may be higher among infants exposed to HIV compared with those unexposed to HIV, and that rates of congenital CMV and HIV co-transmission as well as symptomatic congenital CMV infection are high among infants exposed to HIV.[32]

Brain ultrasound/MRI:

All infants suspected of having congenital CMV infection should have a cerebral ultrasound, with brain MRI, to determine neurological involvement at baseline.

Intracranial calcifications, microcephaly, cerebral ventricular enlargement, and abnormalities of the white matter may be detected.[46]

Antenatal screening for CMV

Antenatal CMV screening is not routinely performed, but is advised if the mother has mononucleosis-like symptoms or if there are fetal abnormalities on antenatal ultrasound. It can be offered to mothers who request testing.[28]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer