Aetiology

Hyperglycaemia is considered the principal aetiological factor in diabetic retinopathy. This affects retinal vasculature and neural retinal elements.

The retina has two circulations: the retinal vasculature supplying the inner retina, and the choroid supplying the outer retina. Diabetes principally affects the inner retina, and its clinical manifestations are apparent as derangement of the retinal vasculature, initially capillaries and later veins.

Hyperglycaemia results in changes to:

Blood composition, including increased viscosity, reduced white cell deformability, and changes in procoagulant, anti-fibrinolytic, and platelet aggregation activity[15][16][17]

Blood vessel walls, including loss of the normally anti-thrombogenic nature of the endothelial lining of retinal blood vessels[18]

Blood flow as a result of leukostasis, microthrombus formation, vascular occlusion, and impairment of retinal autoregulation.[19]

Hyperglycaemia may damage retinal ganglion cells directly, as suggested by structural and functional neurodegenerative changes in the retina prior to the development of clinical signs of diabetic retinopathy.[20][21][22][23][24]

Genetic factors were found to account for 25% to 50% of an individual's risk for developing severe retinopathy in familial aggregation and twin studies.[25][26] Potential candidate retinopathy susceptibility genes have been identified.[27]

Pathophysiology

Retinal microvascular changes

Early diabetic retinopathy is characterised by apoptosis of retinal pericytes and vascular endothelial cells, possibly as a result of hyperglycaemia, together with thickening of the vascular endothelial basement membrane.[28][29] These changes lead to capillary occlusion and ischaemia, with upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).[30][31] VEGF, through phosphorylation of endothelial cell tight junctions and breakdown of the inner blood retinal barrier, promotes increased vascular permeability, and also stimulates endothelial cell proliferation.[32][33] Angiopoietin-2, which blocks the endothelial receptor tyrosine kinase Tie2, may also contribute to increased vascular permeability.[34]

Ranibizumab, bevacizumab, and aflibercept, which bind VEGF, are the mainstay of current treatment of diabetic macular oedema.[35] A 2021 study also suggests improvement in retinopathy severity in severe non-proliferative, and proliferative diabetic retinopathy.[36] Faricimab, a bispecific monoclonal antibody, binds VEGF and angiopoietin-2, and shows promise in the management of diabetic macular oedema.[37]

Inflammation

Diabetic retinopathy is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation. Adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1 promote leukocyte-endothelium binding and leukostasis.[38] Inflammatory cytokines stimulate attraction, activation, and intraretinal migration of leukocytes.[39][40] Further release of cytokines from leukocytes stimulates the release of reactive oxygen species, and increases vascular permeability, in addition to amplifying the response.[41] Retinal glial cells are also thought to initiate and increase inflammation.[42] VEGF is also pro-inflammatory.[43]

Intravitreal dexamethasone and fluocinolone acetonide, through anti-inflammatory action and down-regulation of VEGF, are effective in the treatment of diabetic macular oedema.[44][45]

Neurodegeneration

In patients with diabetes, there is upregulation of proapoptotic molecules in retinal ganglion cells.[46] Oxidative stress may also contribute to retinal neural apoptosis.[47]

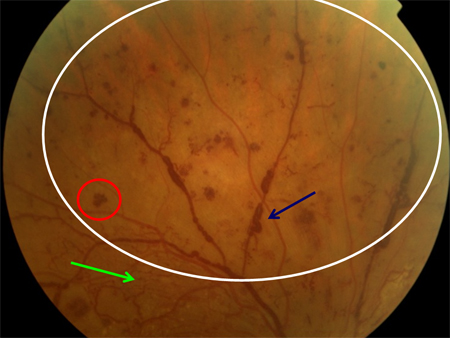

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy: intraretinal microvascular abnormality (IRMA; green arrow), venous beading and segmentation (blue arrow), cluster haemorrhage (red circle), featureless retina suggestive of capillary non-perfusion (white ellipse)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy with macular oedema: exudate (yellow arrow)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends].

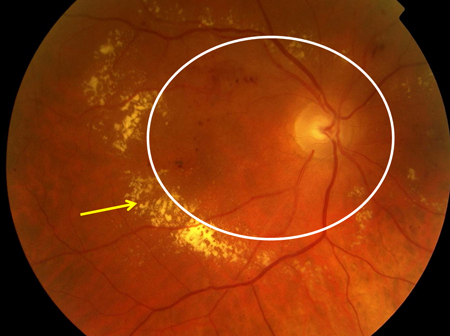

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy with macular oedema: exudate (yellow arrow)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy with macular oedema: thickened retina (white ellipse), exudate (yellow arrow)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends].

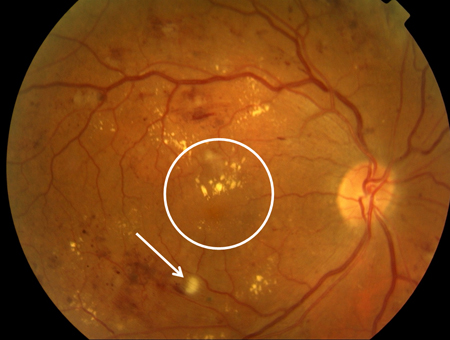

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy with macular oedema: thickened retina (white ellipse), exudate (yellow arrow)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy with macular oedema: cotton wool spot (white arrow), thickened retina (white circle)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends].

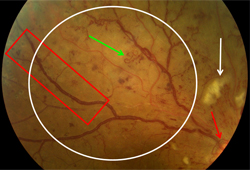

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy with macular oedema: cotton wool spot (white arrow), thickened retina (white circle)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proliferative diabetic retinopathy: optic disc new vessels (red arrow), intraretinal microvascular abnormality (IRMA; green arrow), cotton wool spot (white arrow), venous beading and segmentation (red rectangle), featureless retina suggestive of capillary non-perfusion (white ellipse)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends].

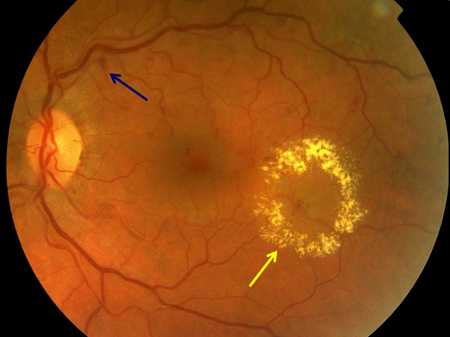

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proliferative diabetic retinopathy: optic disc new vessels (red arrow), intraretinal microvascular abnormality (IRMA; green arrow), cotton wool spot (white arrow), venous beading and segmentation (red rectangle), featureless retina suggestive of capillary non-perfusion (white ellipse)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy with macular oedema: nerve fibre layer haemorrhage (blue arrow), exudate (yellow arrow)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends].

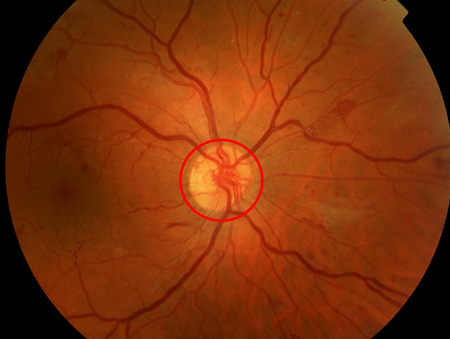

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy with macular oedema: nerve fibre layer haemorrhage (blue arrow), exudate (yellow arrow)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proliferative diabetic retinopathy: new vessels on the optic disc (red circle)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends].

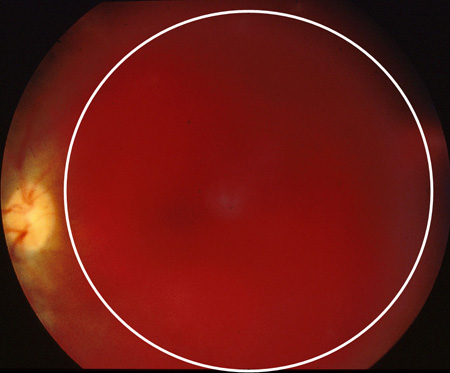

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proliferative diabetic retinopathy: new vessels on the optic disc (red circle)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proliferative diabetic retinopathy: extensive vitreous haemorrhage obscuring most of fundus (white circle)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends].

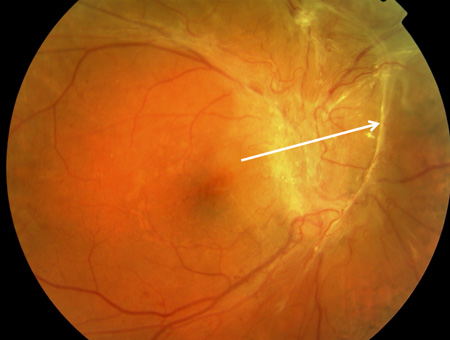

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proliferative diabetic retinopathy: extensive vitreous haemorrhage obscuring most of fundus (white circle)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proliferative diabetic retinopathy: traction towards optic disc and consequent total retinal detachment (white block arrow)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proliferative diabetic retinopathy: traction towards optic disc and consequent total retinal detachment (white block arrow)Courtesy of Moorfields Photographic Archive; used with permission [Citation ends].

Classification

The two mechanisms by which diabetic retinal disease damages vision are:

Progression of retinopathy to new vessel formation, vitreous haemorrhage, and severe visual loss (managed principally with laser). The risk is defined by the retinopathy severity scale below.

Diabetic macular oedema with moderate visual loss (managed principally with intravitreal anti-VEGF injections). The risk is defined by the diabetic macular oedema definition below.

Proposed international clinical severity scale for diabetic retinopathy[1]

The following list shows how the severity of retinopathy corresponds with the signs seen on dilated fundoscopy:

No apparent retinopathy: no abnormalities

Mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR): microaneurysms only

Moderate NPDR: more than just microaneurysms but less than severe NPDR

Severe NPDR: no signs of proliferative retinopathy, with any of the following: more than 20 intraretinal haemorrhages in each of four quadrants; definite venous beading in two or more quadrants; prominent intraretinal microvascular abnormalities in one or more quadrants

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy: one or more of the following: neovascularisation, vitreous/preretinal haemorrhage.

Patients with non-clearing vitreous haemorrhage or macular traction detachment are considered to have advanced proliferative retinopathy. Patients with iris neovascularisation are considered to have proliferative retinopathy.

Classification of diabetic macular oedema[2]

Based on optical coherence tomography, determine whether macular oedema is present (central subfield thickness greater than 300 micrometres), and if so, whether centre-involving or non-centre-involving, and then subclassify according to visual acuity:

Non-centre-involving diabetic macular oedema (NCIDMO)

Centre-involving diabetic macular oedema (CIDMO): increased thickness of central 1 mm of macula felt to be the cause of visual loss.

Sub-classification of visual acuity (VA):

VA better than 6/9

VA 6/9 to 6/18

VA 6/18 to 6/96.

Classification combining macular oedema and retinopathy severity

Mild to moderate non-proliferative retinopathy

No DMO

NCIDMO

CIDMO VA better than 6/9

CIDMO VA 6/9 to 6/18

CIDMO VA 6/18 to 6/96

Severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

No DMO

NCIDMO

CIDMO VA better than 6/9

CIDMO VA 6/9 to 6/18

CIDMO VA 6/18 to 6/96

Proliferative retinopathy

No DMO

NCIDMO

CIDMO VA better than 6/9

CIDMO VA 6/9 to 6/18

CIDMO VA 6/18 to 6/96

Iris neovascularisation

Advanced proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Scale used for screening in primary care in the UK

In the UK National Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Programme, the international retinopathy severity scale is contracted to:[3]

R0 - no retinopathy

R1 - mild/moderate non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

R2 - severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

R3 - proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

In the UK National Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Programme, the following definition of macular oedema (M1) is used:

Exudate within one disc diameter of the centre of the fovea, OR

Circinate or group of exudates within the macula, OR

Any microaneurysm or haemorrhage within one disc diameter of the centre of the fovea if associated with best corrected visual acuity of less than 6/12.

If these criteria are not met, the grade M0 is used.

Grades can be combined for retinopathy and macular oedema: for example, right R2 M0, left R3 M1.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer