Recommendations

Urgent

Use the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol to assess and stabilise any patient with suspected trauma. Start with a rapid primary survey using a <C>ABCDE approach:[13][24]

Catastrophic haemorrhage

Airway with in-line spinal immobilisation

Breathing

Circulation

Disability (neurological)

Exposure and environment.

Protect the patient's cervical spine with manual in-line spinal immobilisation (particularly during any airway intervention) at all stages of the assessment for spinal injury or if the assessment cannot be done.[13] See Management recommendations section.

If you suspect a head injury see our topic Assessment of traumatic brain injury.

Assess the patient for spinal injury. Check if the patient:[13]

Has any significant distracting injuries

Is under the influence of drugs or alcohol

Is confused or uncooperative

Has a reduced level of consciousness

Has any spinal pain

Has any hand or foot weakness (motor assessment)

Has altered or absent sensation in the hands or feet (sensory assessment)

Has priapism

Has paradoxical breathing

Has a history of past spinal problems, including previous spinal surgery or conditions that predispose to instability of the spine (e.g., ankylosing spondylitis).

In alert (Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS] score=15) and stable patients, assess whether the patient is at high, low, or no risk for cervical spine injury using the Canadian C-spine rule (see flowchart below).[13][25] [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ]

Request an urgent CT scan of the cervical spine in any trauma patient who is identified by the Canadian C-spine rule as having:[13][14]

A high-risk factor for cervical spine injury

A low-risk factor for cervical spine injury AND they are unable to actively rotate their neck 45 degrees to both left and right.

CT C-spine should also be performed if there is strong suspicion of thoracic or lumbosacral spine injury associated with abnormal neurological signs or symptoms.[26]

Request an urgent CT scan of the cervical spine in any trauma patient with head injury if:[14][27]

The patient has an altered level of consciousness (GCS <12 on initial assessment)

The patient has been intubated

A definitive diagnosis of C-spine injury is needed urgently (e.g., C-spine manipulation needed for surgery/anaesthesia)

There has been blunt polytrauma involving the head and chest, abdomen or pelvis in someone who is alert and stable

There is clinical suspicion of C-spine injury and any of:

Age 65 or over

Dangerous mechanism of injury

Focal peripheral neurological deficit

Paraesthesia in upper or lower limbs

Refer urgently to a neurosurgeon or spinal surgeon any patient with clinical signs of a spinal cord injury (i.e., an abnormal neurological exam).

For patients with suspected thoracic or lumbosacral spine injury, see our topic Thoracolumbar spine trauma.

Key Recommendations

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Canadian C-spine rule. A&E, accident and emergency department; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; MVC, Motor vehicle collision. ✝Adapted from Stiell IG, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule for radiography in alert and stable trauma patients. JAMA. 2001 17;286(15):1841-8. [Citation ends].

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends CT scanning first line in adults who are identified by the Canadian C-spine rule as requiring imaging.[14] CT images should be interpreted immediately by a healthcare professional trained in this area (e.g., senior musculoskeletal radiologist).[13][27] Consult with a neurosurgeon or spinal surgeon if any abnormalities are reported.[14]

If a cervical spine injury or a fracture is identified, a CT scan of the whole spine is indicated to identify a concomitant thoracolumbosacral fracture.[13]

If the CT cervical spine scan is reported as ‘normal’ by the expert interpreting the results and the neurological exam is normal, significant spinal injury can be excluded.[27]

Seek specialist advice if you are unsure as to whether you can remove the spinal precautions, particularly in patients with a normal CT scan and no neurological deficits but with persistent neck pain/midline tenderness.

Do not request plain cervical spine x-rays for patients with suspected cervical spine injury in the acute phase in the accident and emergency department or trauma department.

Use the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol to assess and stabilise any patient with suspected trauma. Start with a rapid primary survey using a <C>ABCDE approach:[13][24]

Catastrophic haemorrhage

Airway with in-line spinal immobilisation

Breathing

Circulation

Disability (neurological)

Exposure and environment.

Protect the patient's cervical spine with manual in-line spinal immobilisation (particularly during any airway intervention) at all stages of the assessment for spinal injury or if the assessment cannot be done.[13] See Management recommendations section.

The aim of the assessment is to exclude the possibility of an unstable cervical spine injury that could potentially cause spinal cord injury compression and neurological compromise. Maintain in-line neck immobilisation until the spine is cleared.

Assess the patient for spinal injury. Check if the patient:[13]

Has any significant distracting injuries

Is under the influence of drugs or alcohol

Is confused or uncooperative

Has a reduced level of consciousness

Has any spinal pain

Has any hand or foot weakness (motor assessment)

Has altered or absent sensation in the hands or feet (sensory assessment)

Has priapism

Has paradoxical breathing

Has a history of past spinal problems, including previous spinal surgery or conditions that predispose to instability of the spine (e.g., ankylosing spondylitis).

If you suspect a head injury or thoracic or lumbosacral spine injury, see our topics Assessment of traumatic brain injury and Thoracolumbar spine trauma.

Clearing the cervical spine

Use the Canadian C-spine rule (see flowchart below) in alert (GCS=15) and stable patients to assess whether they are at high, low, or no risk for a cervical spine injury.[13][25] [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ]

When clearing the spine, be aware that the range of the neck movement can only be assessed safely if the person is at low risk and there are no high-risk factors.

The Canadian C-spine rule excludes cervical spine injury (clears the cervical spine) clinically in alert (GCS=15) and stable patients with neck pain after blunt trauma without the need for imaging.[13][25]

Most patients presenting to the accident and emergency department with trauma are alert and cooperative. Patients with an altered level of consciousness (GCS <15), uncooperative patients or patients with distracting injuries that exclude reliable clinical assessment, should undergo an urgent CT scan of the spine to clear the spine (see Imaging section below).[14]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Canadian C-spine rule. A&E, accident and emergency department; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; MVC, Motor vehicle collision. ✝Adapted from Stiell IG, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule for radiography in alert and stable trauma patients. JAMA. 2001 17;286(15):1841-8. [Citation ends].

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends CT scanning first line in adults who are identified by the Canadian C-spine rule as requiring imaging.[14]

Practical tip

People aged >65 years are at high risk of cervical spine injury from relatively minor mechanisms of injury (e.g., falling from standing). Always consider the possibility of a neck injury in an older patient with a fall and head injury. See our topic Assessment of traumatic brain injury, acute.

Evidence: Canadian C-spine rule to exclude cervical spine injury in alert and stable patients without imaging

Evidence supports the Canadian C-spine rule as the assessment tool of choice to clinically exclude cervical spine injury in alert and stable patients, without the need for imaging.

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2016 guideline on spinal injury reviewed the evidence for tools used in people with suspected spinal injury, who are alert and stable, to exclude spinal cord injury or isolated spinal column injury.[26] It found evidence for two tools, both of which focused on cervical spine injury.

The Canadian C-spine rule, for which there was the derivation study and 5 validation studies in adults.[25]

The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) low-risk criteria, for which there was the derivation study and 7 validation studies in adults.[28]

The reference standard was plain C-spine x-rays (with additional CT or MRI scanning at the discretion of the treating physician) or cervical spine CT. Patients who did not have any imaging had a follow-up telephone call at 14 days.

The primary outcome was sensitivity, as the guideline group felt there was significant harm associated with false negative results.

Pooled data for the NEXUS low-risk criteria (5 studies, n=45,720) showed a high sensitivity (0.94 [95% CI 0.78 to 0.98]) and very poor specificity (0.25 [95% CI 0.12 to 0.46]).

One study in people aged ≥65 years (n=2963) had similar results (sensitivity 1.00 [95% CI, 0.63 to 1.00]; specificity 0.14 [95% CI, 0.13 to 0.15]).

Data for the Canadian C-spine rule (4 studies, n=22,964) was not pooled as a minimum of 5 diagnostic studies was required for meta-analysis. The median sensitivity was 1.00 (95% CI, 0.63 to 1.00) and median specificity 0.33 (95% CI, 0.31 to 0.36).

3 studies considered modifications to the NEXUS criteria or the Canadian C-spine rule. None of these performed better than the standard Canadian C-spine rule.

No harms were reported for the Canadian C-spine rule or NEXUS low-risk criteria.

The quality of the evidence as assessed by GRADE was very low for all outcomes, due mainly to the studies being observational and the inconsistency of results between studies.

The NICE guideline recommendation to use the Canadian C-spine rule in preference to the NEXUS low-risk criteria takes into consideration the fact that the Canadian C-spine rule studies are generally more precise with consistently higher sensitivity ratings, despite the lack of a meta-analysis for the diagnostic accuracy of the rule.

Take a focused history. For patients who are unconscious or under the influence of alcohol or drugs, take a history from next of kin or paramedics where possible. Ask about:

Mode and mechanism of injury

The most common mechanisms of injury include motor vehicle accidents, pedestrian trauma, violence, falls, and sports injuries. Ask patients:

What happened when their injury occurred?

If they fell, how far did they fall?

Were they involved in a high speed accident? If the patient was in a road traffic accident, was their vehicle overturned? Were they ejected from the vehicle?

Did they attempt to sit up, stand or walk following the fall/accident?

Symptoms

Any neck pain?

Determine location (e.g., level, midline vs. lateral), severity, quality (sharp or shooting into extremities vs. dull and aching), and whether there is radiation to shoulders, down the spine or into the limbs.

Some patients will not be able to specify whether they have neck pain because of distracting injuries. Presume the spine is unstable until you have cleared the cervical spine with a CT scan.

Any paraesthesia in the limbs?

Suggests potential neurological injury from spinal cord or nerve root compression or compromise.

Risk factors for cervical spine injury

Age 18 to 25 years or >65 years:

Cervical spine injuries are encountered at all ages, but approximately 80% of injuries occur in patients aged 18 to 25 years. This age group is generally associated with higher velocity injuries consequent to motor vehicle accidents, while older people experience cervical spine injuries from relatively minor mechanisms of injury (e.g., falling from standing).

Dangerous mechanism of injury:

A fall from a height >1 metre or 5 steps

An axial load to the head (e.g., diving, high-speed motor vehicle collision, rollover motor accident, ejection from a motor vehicle, accident involving motorised recreational vehicles, bicycle collision, horse riding accident).

Distracting traumatic injuries:

Injuries such as limb fractures or chest and abdominal injuries can make the assessment of cervical spine difficult.

Approximately one third of patients with cervical spine and/or spinal cord injuries have an associated head injury.[17] See our topic Assessment of traumatic brain injury, acute.

Practical tip

Cervical spine fractures can be missed in patients with distracting injuries or reduced consciousness, or in those under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

Assess the patient’s level of consciousness using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ]

Consider any patient with a reduced level of consciousness to be at risk for acute cervical spine injury until you have performed a complete assessment.

Perform a cervical spine examination:

Look for any bruising, obvious deformity, and any penetrating injuries around the face, neck, and forehead

Examine the neck and gently palpate for midline cervical tenderness, step deformity, or crepitus.

Perform a full neurological examination:

Assess tone, sensation, power, and reflexes in all four limbs

Evaluate the strength and sensation (light touch and pinprick) for all myotomes and dermatomes, respectively.

Check deep tendon reflexes. These should be elicited in the upper and lower limbs.

Check Hoffman's sign (i.e., adduction of the thumb when flicking the nail of an extended finger on the same hand) and Babinski's sign (i.e., an upgoing plantar response)

Perform a cranial nerve examination.

If you suspect a spinal cord injury, complete an ASIA (American Spinal Injury Association) chart as soon as possible and refer urgently to a neurosurgeon or spinal surgeon.[13] ASIA: International Standards for Neurological Classification of SCI (ISNCSCI) worksheet Opens in new window

A spinal cord injury may produce a classic pyramidal distribution of weakness, with flexors stronger than extensors in the upper extremities and extensors stronger than flexors in the lower extremities.

Suspect a spinal cord injury in any patient with urinary retention or urinary/faecal incontinence and in any male with priapism. Perform a rectal examination to assess for bulbocavernosus reflex (spinal shock) in catheterised patients.

Practical tip

Remove the spine immobilisation in conscious and cooperative patients in a controlled fashion to perform the examination. Ask other members of staff for help to keep the spine immobilised by supporting the patient's head and neck manually in a fixed position while the head blocks are removed and, if appropriate, the collar is opened and gently slid out. Perform a spinal log roll if necessary during examination. Remember that a clinical examination of the whole spine is mandatory as part of the assessment of any patient with a significant history of trauma, with an in-line log role as per Advanced Trauma Life Support protocols.

In practice, the cervical spine is kept immobilised with a collar if the patient has midline cervical tenderness at any time during the physical examination.

If the patient has no midline tenderness during the physical examination and has no neurological deficit, ask them to rotate their head 45 degrees right and left:

If the patient reports pain while moving the neck to the right and left, keep the collar on and request a high-resolution CT scan of the cervical spine to clear the spine radiologically

If the patient does not report pain during cervical spine movements and there are no distracting injuries, you can clear the cervical spine clinically and remove the collar (as per the Canadian C-spine rule). However, request a CT of the cervical spine in patients with:

A dangerous mechanism of injury

Age ≥65 years

Associated head injuries.

Practical tip

Do not attempt to put a collar on a patient who is holding their neck in a fixed position (e.g., a person with ankylosing spondylitis). You may need to allow patients who are uncooperative, agitated, or distressed to assume a position they find comfortable for manual in-line mobilisation.

In ankylosing spondylitis, maintain the neck in the original flexed position that the patient is used to, guided by the extent of the ceiling they are able to see when laid supine.

CT cervical spine

Request an urgent high-resolution CT scan of the cervical spine in any trauma patient with head injury if:[14][27]

The patient has an altered level of consciousness (GCS <12 on initial assessment)

The patient has been intubated

A definitive diagnosis of C-spine injury is needed urgently (e.g., C-spine manipulation needed for surgery/anaesthesia)

There has been blunt polytrauma involving the head and chest, abdomen or pelvis in someone who is alert and stable

There is clinical suspicion of C-spine injury and any of:

Age 65 or over

Dangerous mechanism of injury

Focal peripheral neurological deficit

Paraesthesia in upper or lower limbs

Is identified by the Canadian C-spine rule as having:[13]

A high-risk factor for cervical spine injury

A low-risk factor for cervical spine injury AND they are unable to actively rotate their neck 45 degrees to both left and right.

Request a thin slice (2-3 mm) helical CT scan from the base of the skull to T4 with both sagittal and coronal reconstructions.[27]

The CT scan should be performed within 1 hour of being requested to the radiology team or when the patient is sufficiently stable.[14] CT images should be interpreted immediately by a healthcare professional trained in this area (e.g., senior musculoskeletal radiologist).[13]

Consult with a neurosurgeon or spinal surgeon over any abnormalities on the CT cervical spine scan.[14] Findings may include cervical spine vertebral misalignment, fracture, and pre-vertebral soft-tissue swelling.

If a cervical spine injury or a fracture is identified, a CT scan of the whole spine is indicated to identify a concomitant thoracolumbosacral fracture.[13] See our topic Thoracolumbar spine trauma.

Practical tip

Common cervical spine injuries include:

Odontoid fractures (common in older people)

Hangman fractures (common in extension type injuries)

Vertebral body compression/burst fractures

Bilateral facet dislocation (can occur in flexion type injuries)

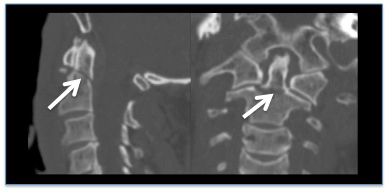

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Common fracture patterns with severe cervical spine trauma. Top: axial CT image showing a cervical burst fracture at C5 level. Bottom: axial CT showing fracture dislocation at C6-C7 level.From the personal collection of Michael G. Fehlings [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT reconstruction demonstrating undisplaced odontoid fractureFrom the personal collection of Michael G. Fehlings [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT reconstruction demonstrating undisplaced odontoid fractureFrom the personal collection of Michael G. Fehlings [Citation ends].

Be aware that there is no role for plain cervical spine x-rays in the investigation of patients with suspected cervical spine injury in the acute phase in the accident and emergency department or trauma department.

Normal CT scan

If the CT cervical spine scan is reported as ‘normal’ and the neurological examination was normal, remove the spinal precautions.[27] This is especially important for intubated patients in the intensive care unit.

The British Orthopaedic Association (BOA) recommends that a senior radiologist reports spinal clearance images before removing the spinal precautions.[27] Optimally this is done by a musculoskeletal radiologist in conjunction with a neurosurgeon or spinal surgeon.

Seek specialist advice if you are unsure as to whether you can remove the spinal precautions, particularly in patients with a normal CT scan and no neurological deficits but with persistent neck pain/midline tenderness. Further imaging, such as an MRI, may be indicated.

Practical tip

Cervical spine immobilisation is associated with adverse effects (e.g., raised intracranial pressure, pain, pressure sores). You should remove the spinal precautions as soon as it is safe and feasible (i.e., as soon as the cervical spine has been cleared by the CT scan, if no abnormalities have been identified).

MRI cervical spine

Refer urgently to a neurosurgeon or spinal surgeon any patient with clinical signs of a spinal cord injury (i.e., an abnormal neurological exam).

An MRI of the spine is indicated (in addition to the CT) in these patients.[13]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer