Recommendations

Key Recommendations

Discuss the patient immediately with a regional vascular service to consider transfer for urgent surgical repair if they have suspected ruptured or symptomatic AAA and bedside aortic ultrasound has confirmed the presence of an AAA or is non-diagnostic or not available.[42] Do not delay diagnosis and management of a ruptured AAA while waiting for the results of imaging.[69]

If the patient has a ruptured AAA, initiate hypotensive resuscitation (permissive hypotension) if they are conscious.[3][69]

The European Society for Vascular Surgery recommends aiming for a target systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 70-90 mmHg.[3] In practice, this target SBP is a good approach if definitive surgical repair is imminent.

However, the Royal College of Emergency Medicine recommends a higher target SBP of 90-120 mmHg, which may be used by the emergency department team to ensure adequate perfusion while waiting for input from a regional vascular service.[69]

Use blood and blood products, if available, with a suggested ratio of fresh frozen plasma/red blood cells close to 1:1.[3][76]

If the patient has a symptomatic, unruptured AAA, urgent surgical repair should be considered regardless of AAA diameter because development of new or worsening pain may herald AAA expansion and impending rupture.[9][42]

If a patient has been accepted by a regional vascular service, ensure they leave the referring unit within 30 minutes of the decision to transfer.[42][69]

Once the patient is stable and urgent surgical repair, if indicated, has been prioritised, infectious or inflammatory aetiology should be addressed.

If the patient has a suspected infectious aneurysm, early diagnosis, prompt treatment with antibiotics, and urgent surgical repair is essential to improve outcomes.[3]

Inflammatory aortitis (caused by, for example, Takayasu's arteritis or giant cell arteritis) is treated with high-dose corticosteroids and surgery.[9][100]

If the patient has an incidental finding of an asymptomatic AAA (outside of a screening programme) refer them to a regional vascular service for consideration of elective surgical repair or conservative management.[42]

In the UK, ensure they are seen:[42]

Within 2 weeks of diagnosis if their AAA measures ≥5.5 cm

Within 12 weeks of diagnosis if their AAA measures 3.0 to 5.4 cm.

The decision to proceed with surgical repair is based on the size of the AAA, as well as the patient’s overall health and preference.[3][42] Patients with an AAA that measures ≥5.5 cm or is >4.0 cm and growing rapidly (>1 cm in 1 year) should generally undergo surgical repair.[3][42]

Bear in mind that the threshold for referral and surgical repair based on size of AAA may vary in different countries.[3][42]

If the patient does not meet the threshold for surgical repair, they should have conservative management, which involves risk factor modification and surveillance with aortic ultrasound.[3][42]

Smoking cessation is key to management; smoking is the most important risk factor for development, expansion, and rupture of AAA.[3][42]

Initial supportive care

If the patient has a suspected ruptured AAA, get immediate help from a senior colleague and discuss the patient with a regional vascular service for consideration of transfer for urgent surgical repair if:[42]

AAA is confirmed on bedside aortic ultrasound

OR

Bedside aortic ultrasound is not immediately available or is non-diagnostic but AAA is still suspected.

Do not delay diagnosis and management of a ruptured AAA while waiting for the results of imaging.[69]

If the patient has been accepted by a regional vascular service, ensure they leave the referring unit within 30 minutes of the decision to transfer.[42][69]

Initiate immediate resuscitation measures while waiting for transfer. These include:

Supplemental oxygen

Large bore peripheral venous access

Arterial catheter; urinary catheter

Hypotensive resuscitation (permissive hypotension) if the patient is conscious.[3]

The European Society for Vascular Surgery recommends aiming for a target systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 70-90 mmHg preoperatively by restricting fluid resuscitation.[3] In practice, this target SBP is a good approach if definitive surgical repair is imminent.

However, the Royal College of Emergency Medicine recommends a higher target SBP of 90-120 mmHg, which may be used by the emergency department team to ensure adequate perfusion while waiting for input from a regional vascular service.[69]

If available, use blood and blood products with a suggested ratio of fresh frozen plasma/red blood cells close to 1:1.[3][76]

How to insert a tracheal tube in an adult using a laryngoscope.

How to use bag-valve-mask apparatus to deliver ventilatory support to adults. Video demonstrates the two-person technique.

More info: Permissive hypotension

Permissive hypotension is recommended for conscious patients with suspected ruptured AAA. However, there is no direct randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence for this approach. Therefore, recommendations are based on expert opinion and made by consensus, and the thresholds for systolic blood pressure (SBP) remain unclear.

There is no standard definition of permissive hypotension. Therefore, there is also a lack of agreement on how to achieve it and the target parameters used to monitor it.[42]

The European Society for Vascular Surgery recommends aiming for a target SBP of 70-90 mmHg.[3]

In practice, this target SBP is a good approach if definitive surgical repair is imminent.

However, the Royal College of Emergency Medicine recommends a higher target SBP of 90-120 mmHg, which may be used by the emergency department team to ensure adequate perfusion while waiting for input from a regional vascular service.[69]

A Cochrane review of controlled (permissive) hypotension versus a normotensive resuscitation strategy for people with ruptured AAA (search date August 2017) found no RCTs that met the inclusion criteria.[105]

The Cochrane review noted that one RCT in an indirect population of adult trauma patients with haemorrhagic shock found reduced mortality and lower blood and fluid requirements with permissive hypotension compared with a conventional resuscitation strategy.[106]

However, the review authors noted that this may not be generalisable as people with ruptured AAA were usually older and more likely to have coronary and renal atherosclerotic disease, and therefore at greater risk of myocardial infarction and renal insufficiency if submitted to low SBP levels compared with younger people with trauma.

Indirect evidence supporting the need for caution in patients with ruptured AAA was reported in the Cochrane review from the IMPROVE trial, a multicentre RCT (N=613) comparing endovascular versus open aneurysm repair. It found that in people with ruptured AAA and a recorded preoperative SBP less than 70 mmHg, mortality at 30 days was higher (51.0%) compared with people with SBP above 70 mmHg (34.1%).[107]

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) based its 2020 guideline evidence review for permissive hypotension during transfer of people with ruptured AAA to regional vascular services on the Cochrane review.[42] As there was no direct RCT evidence, the guideline committee make a consensus recommendation to: “consider a restrictive approach to volume resuscitation (permissive hypotension) for people with a suspected ruptured or symptomatic AAA during emergency transfer to a regional vascular service”. No SBP targets were given.

Although noting the demographic difference in populations, the committee decided that due to profuse bleeding in both populations the rationale for using restrictive fluid resuscitation in trauma patients was applicable to people with ruptured AAA.

The committee considered potential harms associated with overuse of resuscitative fluids (e.g., dilution of clotting factors, hypocalcaemia, and reduced body temperature) along with potential benefits of a permissive hypotensive resuscitation strategy (e.g., better clotting and reduction in size of haematomas).

Individual patient factors and circumstances such as distance to regional vascular services need to be considered. The committee therefore agreed that vascular specialists should be involved in the decision to commence permissive hypotensive resuscitation strategies, but that otherwise it was likely to have little impact on costs and resources.

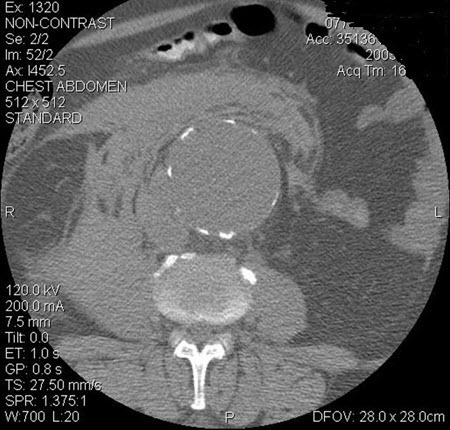

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal aortic aneurysm: CT scan of a ruptured AAAUniversity of Michigan, specifically the cases of Dr Upchurch reflecting the Departments of Vascular Surgery and Radiology [Citation ends].

Urgent surgical repair

Specialist input from a regional vascular service should inform the decision to transfer a patient and their suitability for urgent surgical repair.[3][69]

No single symptom, sign, or patient-related risk factor, or patient risk assessment tool (scoring system), should be used to determine whether surgical repair is suitable for a patient.[42]

However, certain patients (such as those who are in cardiac arrest and/or have a persistent loss of consciousness) are unlikely to survive surgical repair.[3][42]

If surgery is deemed appropriate, either endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) or open surgical repair may be performed.[3][42] Ensure the patient has appropriate perioperative care - see Surgical repair below for more information.

More info: Mortality of ruptured AAA

In patients with confirmed ruptured AAA, 3-year mortality was lower among those randomised to EVAR than to an open repair strategy (48% vs. 56%; hazard ratio [HR] 0.57, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.90).[108] The difference between treatment groups was no longer evident after 7 years of follow-up (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.13). Re-intervention rates were not significantly different between the randomised groups at 3 years (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.32).[108] There is some evidence to suggest that an endovascular strategy for repair of ruptured AAA may reduce mortality more effectively in women than in men.[108][109]

A systematic review and meta-analysis found that 30-day and 1-year mortality rates following repair of ruptured AAA in patients aged ≥80 years were similar to patients of other ages, with a significant survival benefit of EVAR over open repair.[110]

There is some evidence to suggest that mode of anaesthesia for operative repair of AAA affects outcomes.[111] The IMPROVE multicentre randomised controlled trial detected a significantly reduced 30-day mortality in patients who had EVAR under local anaesthesia alone compared with general anaesthesia (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 0.27, 95% CI 0.1 to 0.7).[107] These findings were replicated in a separate meta-analysis comparing mode of anaesthesia for endovascular repair of ruptured AAA.[112] Data from the UK’s National Vascular Registry (9783 patients who received an elective, standard infrarenal EVAR; general anaesthetic, n=7069; regional anaesthetic, n=2347; local anaesthetic, n=367) showed a lower 30-day mortality rate after regional versus general anaesthesia.[113]

However, a subsequent systematic review did not show any mortality benefit with local anaesthesia, but did demonstrate shorter hospital stays.[114] The international multicentre Endurant Stent Graft Natural Selection Global Post-Market Registry (ENGAGE) study examined the outcomes of 1231 patients undergoing EVAR under general (62% of patients), regional (27%), and local (11%) anaesthesia.[115] The type of anaesthesia had no influence on perioperative mortality or morbidity but the use of local or regional anaesthesia during EVAR appeared to be beneficial in decreasing procedure time, need for ICU admission, and duration of postoperative hospital stay.[115] In 2024, the European Society for Vascular Surgery issued a weak recommendation favouring local anaesthesia over general anaesthesia in elective settings, based on potential reduction in procedure time, ICU admissions, and postoperative hospital stay.[3][116][117][118]

If surgical repair is deemed inappropriate, make treatment and monitoring decisions with the multidisciplinary team as part of an individualised end of life care plan.[119] Involve the patient and/or their carers where possible.[119]

Urgently discuss any patient with a symptomatic, unruptured AAA with a regional vascular service.[42][69]

The development of new or worsening pain may herald aneurysm expansion and impending rupture.

Urgent surgical repair is indicated regardless of AAA diameter.[9][42][76]

Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is widely used in the management of patients with symptomatic AAA.[120][121]

Under some circumstances, intervention may be delayed for several hours to optimise conditions to ensure successful repair; these patients should be closely monitored in the ICU.[76]

Ensure the patient has appropriate perioperative care - see Surgical repair below for more information.

More info: EVAR versus open repair of symptomatic AAA

The management of symptomatic but not ruptured AAA is an area of debate, and guideline organisations make different recommendations. Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) may be preferable to open repair if the patient has suitable anatomy.[3]However, open repair may be better for patients with a life expectancy of more than 10 years.[3][42]

In 2024 the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) published updated clinical practice guidelines on the management of AAA.[3] On the issue of EVAR versus open repair, the ESVS recommends an EVAR-first strategy in most scenarios.

However, the ESVS states it is reasonable to consider open repair as a first strategy in younger, fit patients with a long life expectancy >10-15 years because there are indications that an increased rate of complications may occur after 8-10 years with earlier-generation EVAR devices, and durability of current devices is uncertain.[3]

The guideline notes that EVAR cannot entirely replace open surgical repair as it will remain the preferred treatment option for some patients.

UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance published in 2020, however, recommends open repair for the majority of patients with unruptured AAA, including those who are symptomatic, unless contraindicated due to abdominal co-pathology, anaesthetic risk, and/or medical comorbidities. The reasons for this were:[42]

A preference for data collected from randomised controlled trials (RCTs): in particular, the EVAR-1 trial (N=1252) comparing EVAR versus open surgery patients with unruptured AAA[122]

Early (0-6 months) mortality (total and aneurysm-related) was lower in the EVAR group (total mortality adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 0.61, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.02; aneurysm-related mortality adjusted HR 0.47, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.93); however, at >8 years open repair had a significantly lower mortality (total mortality adjusted HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.56; aneurysm-related mortality adjusted HR 5.82, 95% CI 1.64 to 20.65). This difference was mostly due to secondary aneurysm sac rupture in the EVAR group.

Cost-effectiveness modelling

Outcomes (such as shorter hospital stays and perioperative mortality rates) having improved over time for open repair as well as EVAR

Potential of lost experience with open repair if EVAR became the main repair strategy.

Concerns have been raised about the NICE recommendations, including the age of the EVAR-1 trial (enrolment was from 1999-2004) meaning the results may not be applicable to current techniques and that UK-specific data was used for cost-effectiveness in the NICE guideline.[123]

In general, there is little evidence specifically for the subgroup of patients with symptomatic unruptured AAA. It is also worth noting that the EVAR-1 trial did not mention how many of the included patients were symptomatic or do any subgroup analysis for this population.[122]

Other large RCTs in patients with unruptured AAA (OVER, DREAM) also found initial survival benefits with EVAR that reduced over time, but both of these specifically excluded symptomatic patients.[124][125]

In three observational studies, short-term all-cause mortality rates did not differ between EVAR and open repair of symptomatic AAA.[120][121][126]

Data from the 2011-2013 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program suggest that 30-day mortality risk after repair of symptomatic AAA was approximately double that following asymptomatic AAA repair, regardless of surgical approach (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.3 to 3.5).[122]

Symptomatic patients having EVAR were less likely than asymptomatic patients to have a percutaneous attempt for access. They also had longer operating times, with an increased requirement for complex EVAR and a higher risk of major adverse events after EVAR.

For patients with ruptured AAA there is general agreement that EVAR is the preferred approach in the majority of patients (although NICE makes a weaker recommendation for this than ESVS).[3][42]

Bear in mind that the threshold for referral and consideration of surgical repair for an asymptomatic AAA may vary in different countries. Check your local protocol.

Referral

Organise referral to a regional vascular service for any patient with an asymptomatic AAA (that is detected outside of a screening programme). Following diagnosis, ensure they are seen:[42]

Within 2 weeks if the AAA measures ≥5.5 cm

Within 12 weeks if the AAA measures 3.0 to 5.4 cm.

Elective surgical repair versus conservative management

Discuss the risks and benefits of elective surgical repair versus conservative management (with ultrasound surveillance) with the patient based on their current and expected future health.[42] For AAA detected as an incidental finding, conservative management is preferred to repair until the theoretical risk of rupture exceeds the estimated risk of operative mortality.[3][4][42][101]

Treatment decisions should be made jointly with the patient and should take into account factors such as:[3][42]

Aneurysm size and morphology. Surgical repair should generally be considered for asymptomatic AAA if it measures:[42]

The patient’s age, life expectancy, fitness for surgery, and any comorbidities[42]

Assessment should include a medical history and clinical examination, functional assessment, full blood count and electrolytes (including assessment of renal function), and ECG. Additional testing, including static echocardiogram, pulmonary function tests, and cardiopulmonary exercise testing, may be considered based on the individual circumstances of the patient.[3][42]

The risk of AAA rupture if it is not repaired[42]

The short- and long-term benefits and risks, including disadvantages of repair such as stay in hospital, operation risks, recovery period, potential need for other procedures, and the need for surveillance imaging appointments[42]

The uncertainties around estimates of risk for AAAs ≥5.5 cm[42]

In patients with an underlying genetic cause or connective tissue disorder, the threshold diameter for considering repair should be individualised, depending on:[3]

Anatomical features

Underlying genetics: rupture risk is higher at smaller aortic diameters in some conditions, and surgical repair is more challenging in certain disorders owing to the increased arterial wall fragility and anatomy.[3]

Refer any patient who meets the threshold for surgical repair but is not initially fit for surgery to the appropriate specialist for optimisation of their fitness status and comorbidities, before reconsideration of surgical repair.[3] This may include a patient with:[3]

Active cardiovascular disease (e.g., unstable angina, decompensated heart failure, severe valvular disease, significant arrhythmia)

Poor functional capacity (e.g., unable to climb two flights of stairs, walk up a hill, perform heavy housework [scrubbing floor or moving furniture], or mow a lawn)

Significant clinical risk factors (e.g., pre-existing COPD, recent decline in respiratory function, history of symptomatic cerebrovascular disease, severe renal impairment [eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2]).

If a patient is a candidate for surgical repair, ensure they have appropriate perioperative management. See Surgical repair below for more information.

More info: Elective surgical repair mortality

Data suggest that in patients with larger AAAs (ranging from 5.0 to 5.5 cm) undergoing elective repair, endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is equivalent to open repair in terms of long-term overall survival, although the rate of secondary interventions is higher for EVAR.[124][127] EVAR reduces AAA-related mortality (but not longer-term overall survival) in patients with a large AAA (≥5.5 cm) who are unsuitable for open repair.[128] Post-repair, larger AAAs appear to be associated with worse late survival than smaller aneurysms (pooled HR 1.14 per 1-cm increase in AAA diameter, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.18; 12.0- to 91.2-month follow-up).[129] The association is more pronounced with EVAR than with open repair.

Surveillance

If a patient has not reached the threshold to consider surgical repair:[3][42]

Offer surveillance with aortic ultrasound.

Check your local protocol for guidance on frequency of surveillance because this may vary in different countries.[3][9][42]

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends the following intervals for surveillance:[42]

Annually if the AAA measures 3.0 to 4.4 cm

Every 3 months if the AAA measures 4.5 to 5.4 cm.

Offer information, support, and interventions for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.[3][42]

Refer all patients to a stop smoking service. This is key because smoking is the most important risk factor for development, expansion, and rupture of AAA.[3] See Smoking cessation.

All patients with AAA should receive antiplatelet therapy unless contraindicated. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) states that treatment with a single antiplatelet agent (aspirin or clopidogrel) may be reasonable.[130] Anticoagulation can be considered in cases of intraluminal thrombus or occlusive aneurysm, in light of the role of the mural thrombus in aneurysmal progression.[130]

The European Society of Cardiology recommends that all patients with symptomatic peripheral vascular disease should also be started on lipid lowering agents if low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol >2.5 mmol/L (>97 mg/dL), and antihypertensives if systolic blood pressure >140 mmHg, unless contraindicated.[131][132]

Other considerations include:

Strategies targeted at a healthy lifestyle including weight management, diet, nutrition, and exercise. See Obesity in adults.

Management of other comorbidities such as diabetes. See Type 2 diabetes in adults.

More info: Use of antihypertensives to reduce rate of AAA expansion

Short-term treatment with antihypertensives (such as beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors) does not appear to reduce the rate of AAA expansion.[4][133][134][135] Trials in which patients with small AAAs were randomised to propranolol and other beta-blockers with the intention of reducing the rate of aneurysm expansion failed to demonstrate significant protective effects.[135][136] Propranolol was poorly tolerated in these studies.[136] Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies of antihypertensive medications in AAA have not demonstrated any significant difference in rate of AAA growth or incidence of clinical events.[63][133]

More info: Surveillance

For a small asymptomatic AAA, surveillance is preferred to repair until the theoretical risk of rupture exceeds the estimated risk of operative mortality.[4][42][101]

Early surgery for the treatment of smaller AAAs does not reduce all-cause or AAA-specific mortality.[4][137] One systematic review (4 trials, 3314 participants) found high-quality evidence to demonstrate that immediate repair of small AAA (4.0 cm to 5.5 cm) did not improve long-term survival compared with surveillance (adjusted HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.02, mean follow-up 10 years).[137] The lack of benefit attributable to immediate surgery was consistent regardless of patient age, diameter of small aneurysm, and whether repair was endovascular or open.[137]

Surgical referral of smaller AAAs is usually reserved for rapid growth, or once the threshold diameter for aneurysm repair is reached on ultrasonography.[3][4]

Recommendations for surveillance intervals vary.[3][9][42]

One systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data concluded that surveillance intervals of 2 years for 3.0 to 4.4 cm AAA, and 6 months for 4.5 to 5.4 cm AAA, are safe and cost-effective.[95]

Analysis of AAA growth and rupture rates indicated that in order to maintain a AAA rupture risk <1%, an 8.5-year surveillance interval is required for men with baseline AAA diameter of 3.0 cm.[95] The corresponding estimated surveillance interval for men with an initial aneurysm diameter of 5.0 cm was 17 months.

Despite having similar small aneurysm growth rates, rupture rates were four times higher in women than in men.[95] Surveillance programmes and criteria for considering surgery may be tailored for women with opportunistically detected AAA.

Indications

Urgent surgical repair is indicated for any patient with AAA that is ruptured or symptomatic.[3][42]

Elective surgical repair should be considered for an asymptomatic AAA that measures:[3][42]

≥5.5 cm

OR

>4.0 cm and growing rapidly (>1 cm in 1 year).

Perioperative management

Ensure the patient is optimised for surgery, and given antibiotic and venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, and adequate analgesia. Blood transfusion should be considered, and the patient should have appropriate monitoring depending on the type of surgery.

Optimisation for surgery

If the patient has a symptomatic unruptured AAA, ensure they are monitored carefully on ICU with strict management of their blood pressure.[3][76] They should be considered for deferred urgent surgical repair, ideally under elective repair conditions.[3]

If a patient has an asymptomatic AAA:

Offer the patient information, support, and interventions for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.[42] Elective repair in asymptomatic patients allows for preoperative assessment, cardiac risk stratification, and medical optimisation of other comorbidities. Addressing modifiable cardiovascular risk factors preoperatively improves long-term survival after AAA repair.[138] Consider the following:

Referral to a stop smoking service.[42] See Smoking cessation.

Strategies targeted at a healthy lifestyle including weight management, diet, nutrition, and exercise.[42] See Obesity in adults.

All patients with AAA should receive antiplatelet therapy unless contraindicated. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) states that treatment with single antiplatelet agent (aspirin or clopidogrel) may be reasonable.[130] Anticoagulation can be considered in cases of intraluminal thrombus or occlusive aneurysm, in light of the role of the mural thrombus in aneurysmal progression.[130]

Optimisation of their medication.[42]

If a patient is already taking antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy, discuss this with a vascular surgeon. In general:

Continue antiplatelet monotherapy with aspirin or a P2Y 12 inhibitor (e.g., clopidogrel) during the perioperative period after open and endovascular AAA repair.[3]

Avoid continuing dual antiplatelet therapy in most patients due to the risk of serious bleeding.[3] However, continuation may be considered in certain high-risk patients, including those undergoing interventional coronary revascularisation before AAA repair because they are at risk of in-stent thrombosis.[3]

Discontinue anticoagulation prior to surgery for at least:[3]

5 days for warfarin

2 days for direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).

Do not start a beta-blocker prior to AAA repair.[3][42] However, continue a beta-blocker if a patient is already taking this at an appropriate dose.[3]

Lipid modification.[42]

Start a statin at least 4 weeks before elective AAA surgery, if possible, to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality; continue indefinitely.[3][139][140][141] See Hypercholesterolaemia and Hypertriglyceridaemia.

Perioperative statin use reduces cardiovascular events during non-cardiac surgery.[142]

Management of diabetes.[42] See Type 2 diabetes in adults.

Management of hypertension.[42] See Essential hypertension.

More info: Preoperative exercise training

Preoperative exercise training reduced post-surgical cardiac complications in a small randomised controlled trial of patients undergoing open or endovascular AAA repair.[143] A further meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) showed that preoperative exercise training was generally safe for patients with AAA, but concluded that further research is needed to clarify the safety among patients with a large AAA.[144] A Cochrane review and a separate systematic review of prehabilitation (exercise training) prior to AAA surgery did not show any outcome benefit.[145][146] While preoperative exercise training can be beneficial for patients undergoing AAA repair, further investigation with RCTs is needed before it can be recommended more widely.[147]

Antibiotic prophylaxis

Give the patient prophylactic antibiotics if they are undergoing EVAR or open surgical repair to cover gram-positive and gram-negative organisms (i.e., Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and enteric gram-negative bacilli) and prevent graft infection.[3]

Check your local protocol for antibiotic regimens; broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage should be tailored to the patient’s clinical presentation and cultures.

Analgesia

Ensure the patient has adequate pain relief; options include epidural analgesia, patient-controlled analgesia, and placement of catheters for continuous infusion of local anaesthetic agents into the wound.[3]

VTE prophylaxis

Give VTE prophylaxis to all patients undergoing surgical repair of AAA.[76][148]

Consider pharmacological VTE prophylaxis with a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) for a minimum of 7 days for a patient undergoing EVAR or open surgical repair if their risk of VTE outweighs their risk of bleeding.[148]

If pharmacological VTE prophylaxis is contraindicated, consider mechanical VTE prophylaxis with either anti-embolism stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression. Continue use until the patient no longer has significantly reduced mobility relative to their normal or anticipated mobility.[148]

If a patient has a ruptured AAA they are at increased risk of major bleeding but are also at high risk for VTE. Therefore:[3]

Consider using mechanical prophylaxis with intermittent pneumatic compression until the risk of major bleeding has subsided.[3]

Once the risk of major bleeding has subsided (usually within 24-48 hours of surgery unless there are signs of ongoing bleeding or a clinically significant coagulopathy) start pharmacological prophylaxis with either an LMWH or unfractionated heparin.[3]

Continue pharmacological prophylaxis throughout the hospital stay, and also after discharge in certain patients based on individual risk factors and level of mobility.[3]

The European Society for Vascular Surgery also recommends to consider intraoperative administration of heparin once the rupture bleeding has been controlled.[3]

Blood transfusion

Cell salvage or an ultrafiltration device is recommended if large blood loss is anticipated or the risk of disease transmission from banked blood is considered high.[76] Intraoperative cell salvage and re-transfusion should be considered during open AAA repair.[3]

Blood transfusion is recommended if the intraoperative haemoglobin level is <100 g/L in the presence of ongoing blood loss.[76] Consider use of fresh frozen plasma and platelets in a ratio with packed blood cells of 1:1:1.[76][149]

Monitoring

All patients with an AAA undergoing open surgical repair and high-risk patients undergoing endovascular repair should have early postoperative monitoring in an intensive care or high-dependency unit.[3]

Pulmonary artery catheters should not be used routinely in aortic surgery, unless there is a high risk for a major haemodynamic disturbance.[76] Central venous access is recommended for all patients undergoing open aneurysm repair.[76]

Avoiding hypothermia during open repair and EVAR can reduce hospital length of stay, length of stay in the ICU, and rates of organ dysfunction.[150]

Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR)

EVAR provides greater benefit than open surgical repair for a ruptured infrarenal AAA in most patients, particularly for men over 70 years and women of any age.[3][42] Benefits of endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) include lower perioperative mortality, and less time in hospital in general (and critical care in particular).[42][101] However, open surgical repair may provide a better risk/benefit balance for men under 70 years.[42] In young patients with suspected connective tissue disorders and an AAA, open surgical repair is recommended as first option.[3] Local anaesthesia should be considered, if tolerated, for a patient undergoing EVAR.[3][42]

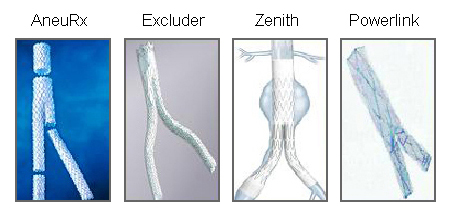

EVAR involves the transfemoral endoluminal delivery of a covered stent graft into the aorta, thus sealing off the aneurysm wall from systemic pressures, preventing rupture, and allowing for sac shrinkage. The endograft can be deployed percutaneously through low-profile devices, or after exposing the femoral arteries surgically. A Cochrane review found no difference between the techniques after short follow-up (6 months), except that the percutaneous approach may be faster.[151]

[  ]

Complex EVAR procedures are evolving techniques and include fenestrated/branched EVAR (see below), and management with chimney grafts.[3] Long-term data for the durability of low-profile devices are lacking.

]

Complex EVAR procedures are evolving techniques and include fenestrated/branched EVAR (see below), and management with chimney grafts.[3] Long-term data for the durability of low-profile devices are lacking.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Various endovascular stent grafts used for endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR)University of Michigan, specifically the cases of Dr Upchurch reflecting the Departments of Vascular Surgery and Radiology [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR)University of Michigan, specifically the cases of Dr Upchurch reflecting the Departments of Vascular Surgery and Radiology [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR)University of Michigan, specifically the cases of Dr Upchurch reflecting the Departments of Vascular Surgery and Radiology [Citation ends].

Assessment of suitability for EVAR should be through the use of 0.5 mm-slice CT angiography. It is essential that the operator is familiar with the specific instructions for use of the endograft to be used.

Complications of EVAR may include endoleak, graft occlusion, and graft migration with aortic neck expansion.[3] Such complications are usually detected on completion angiography or postoperative imaging, though studies suggest that intraoperative CT angiography may be a more sensitive method of detecting complications of EVAR.[152] A systematic review reported aortic neck dilation in 24.6% of EVARs (9439 men included), which led to higher rates of type I endoleak, graft migration, and re-intervention.[153]

As an adjunct to EVAR, either unilateral or bilateral internal iliac artery (IIA) occlusion may be acceptable in certain anatomical situations for patients at high risk for open surgical repair. Buttock claudication will occur in 27.9% of patients following IIA occlusion, although this resolves in 48% of cases after an average of 21.8 months. It is less likely to occur following unilateral occlusion (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.91). Erectile dysfunction occurred in 10% to 14% of men following IIA occlusion.[76][154]

Internal iliac artery revascularisation techniques, involving specialised iliac branch devices, have high technical success rates (up to 97.5%) and are associated with low morbidity (e.g., buttock claudication rate of 2.15% to 4.1%).[155][156] There are a lack of randomised controlled trial data comparing internal iliac artery occlusion with internal artery revascularisation.[157] In patients with synchronous intra-abdominal malignancy, EVAR reduces mortality and delay between the treatment of the two pathologies despite a significant risk for thrombotic events.[158][159]

Lifelong, annual surveillance with ultrasonography or CT is recommended following endovascular repair of AAAs to detect late complications and identify late device failure and disease progression.[3][76]

Open repair

Open repair should be considered for a patient with a ruptured AAA if EVAR is unsuitable.[42] It is likely to provide a better risk/benefit balance in men under 70 years.[42]

Open repair is usually transperitoneal but may be retroperitoneal.[3] With proximal and distal aortic control obtained, the aneurysm is opened, back-bleeding branch arteries are ligated, and a prosthetic graft is sutured from normal proximal aorta to normal distal aorta (or iliac segments). Once flow is restored to the iliac arteries, the aneurysm sac is closed over the graft.[160] A retroperitoneal approach should be considered for patients with aneurysmal disease that extends to the juxtarenal and/or visceral aortic segment, or in the presence of an inflammatory aneurysm, horseshoe kidney, or hostile abdomen.[76][161][162]

Straight tube grafts are recommended for repair in the absence of significant disease of the iliac arteries.[76] The proximal aortic anastomosis should be performed as close to the renal arteries as possible.[76] It is recommended that all portions of an aortic graft should be excluded from direct contact with the intestinal contents of the peritoneal cavity.[76] Re-implantation of a patent inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) should be considered under circumstances that suggest an increased risk of colonic ischaemia (i.e., associated coeliac or superior mesenteric artery occlusive disease, an enlarged meandering mesenteric artery, a history of prior colon resection, inability to preserve hypogastric perfusion, substantial blood loss or intraoperative hypotension, poor IMA back-bleeding when graft open, poor Doppler flow in colonic vessels, or should the colon appear ischaemic).[3][76][163]

Complications of open repair include cardiac and pulmonary events, mesenteric ischaemia, renal failure, bleeding, wound and graft infection, spinal cord ischaemia/paraplegia, embolisation/limb ischaemia, and late graft complications (i.e., aorto-enteric fistula and aortic pseudoaneurysm).[1][164]

Fenestrated EVAR (FEVAR) and branched endografts (bEVAR)

For patients with a complex AAA and standard surgical risk, open repair or EVAR should be considered based on fitness, anatomy, and patient preference. For patients with a complex AAA and high surgical risk, EVAR with fenestrated and branched technologies should be considered as first-line therapy. FEVAR and branched endografts have become the treatment of choice of complex AAAs in most high-volume centres.[3] These procedures are viable alternatives to open repair for juxtarenal and suprarenal AAA, or for those with AAA where a short or diseased neck precludes conventional repair.[3] FEVAR endografts have holes that correspond to the position of branching arteries within the aorta, and permit endovascular repair of complex aneurysms. One pooled analysis of 7 retrospective studies (including 772 patients) suggested favourable mortality and target visceral vessel patency rates (8.0% and 95.4% at 1 year, respectively), though another meta-analysis (7061 patients) suggests no mortality difference with FEVAR, but a potential increased re-intervention hazard; the procedure is performed routinely in some centres.[165][166][167] Branched devices either with inner or outer branches involve more extended aortic coverage compared with fenestrated devices.[3] The European Society for Vascular Surgery states these should be reserved for type 4 thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms (these involve the entire abdominal aorta from the level of the diaphragm to the aortic bifurcation).[3]

Choice of elective repair

Guidelines recommend an individualised approach to surgical choice.[3][9][42][76][168] Factors that will influence the decision include: anatomical determinants (e.g., aneurysm diameter, neck length, neck diameter); life expectancy, sex, and comorbidities; and perioperative risk.[3][42][76][169] EVAR should be considered in patients who are unfit for open surgery who:[42][76][137]

Have high perioperative risk (such as abdominal co-pathology, or anaesthetic risks and/or comorbidities that would be a contraindication to open surgical repair), and

Have anatomy that is congruent with the relevant stent-graft manufacturer's eligibility criteria as determined in the instructions for use, and

Are able to satisfy the mandatory surveillance regimen following surgery.

Patients with lower perioperative risk and favourable anatomy may also be candidates for EVAR.[170][171] Consideration should be given to safety and durability of repair (need for re-intervention).

Open repair may be preferred in patients who:

Have lower perioperative risk, and

Are relatively younger.

In the UK, 61% of elective infrarenal AAAs and 89% of complex AAAs were treated with EVAR during 2018-2020.[172]

Once the patient is stable and urgent surgical repair, if indicated, has been prioritised, infectious or inflammatory aetiology should be addressed.

Infectious AAA

If the patient has a suspected infectious aneurysm, early diagnosis, prompt treatment with antibiotics, and urgent surgical repair is essential to improve outcomes.[3] Open surgical repair has traditionally been considered gold standard for infectious aneurysms, though more recent data suggest that EVAR may be associated with equal or superior outcomes.[3][9][173] Extensive debridement is often needed. There is a high risk of secondary infective complications and further surgery may be needed for new infectious lesions.

Intraoperative cultures should be taken to accurately guide subsequent antibiotic therapy; however, empirical antibiotics are often administered, as peripheral blood cultures and surgical specimen cultures are negative in a large proportion of patients.[9] Prolonged antibiotic therapy (from 4-6 weeks duration to lifelong) may be indicated depending on the specific pathogen, the type of operative repair, and the patient’s immunological state.[3][9]

Inflammatory AAA

Inflammatory aortitis (caused by, for example, Takayasu's arteritis or giant cell arteritis) is treated with high-dose corticosteroids and surgery.[9][100]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer