Signs and symptoms

Patients with early disease are typically asymptomatic; thus, a majority of patients present in advanced stages of the disease when signs and symptoms appear.[2]Fleming GF, Ronette BM, Seidman J, et al. Epithelial ovarian cancer. In: Barakat RR, Markman M, Randall ME, eds. Principles and practice of gynecologic oncology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

Signs and symptoms are typically vague/non-specific and gastrointestinal-related (e.g., abdominal bloating, nausea and emesis, early satiety, dyspepsia, increased abdominal girth, abdominal cramping, and change in bowel habit).[6]Goff BA, Mandel LS, Melancon CH, et al. Frequency of symptoms of ovarian cancer in women presenting to primary care clinics. JAMA. 2004 Jun 9;291(22):2705-12.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/198893

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15187051?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]Goff BA, Mandel L, Muntz HG, et al. Ovarian cancer diagnosis: results of a national ovarian cancer survey. Cancer. 2000 Nov 15;89(10):2068-75.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11066047?tool=bestpractice.com

In one study, approximately 95% of patients reported vague gastrointestinal symptoms before their diagnosis of ovarian cancer, and approximately 75% of patients had these symptoms for at least 3 months.[74]Goff BA, Mandel L, Muntz HG, et al. Ovarian cancer diagnosis: results of a national ovarian cancer survey. Cancer. 2000 Nov 15;89(10):2068-75.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11066047?tool=bestpractice.com

In another study, the combination of bloating, increased abdominal girth, and urinary urgency or frequency was commonly reported in patients with ovarian cancer.[6]Goff BA, Mandel LS, Melancon CH, et al. Frequency of symptoms of ovarian cancer in women presenting to primary care clinics. JAMA. 2004 Jun 9;291(22):2705-12.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/198893

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15187051?tool=bestpractice.com

Some patients with early-stage disease present with pelvic/abdominal pain or pressure due to ovarian torsion.[2]Fleming GF, Ronette BM, Seidman J, et al. Epithelial ovarian cancer. In: Barakat RR, Markman M, Randall ME, eds. Principles and practice of gynecologic oncology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2009. Patients may also have acute onset of lower abdominal pain with associated nausea and emesis. Ovarian cancer must be suspected with any of these signs or symptoms because there are no pathognomonic features associated with this cancer.[6]Goff BA, Mandel LS, Melancon CH, et al. Frequency of symptoms of ovarian cancer in women presenting to primary care clinics. JAMA. 2004 Jun 9;291(22):2705-12.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/198893

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15187051?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]Goff BA, Mandel L, Muntz HG, et al. Ovarian cancer diagnosis: results of a national ovarian cancer survey. Cancer. 2000 Nov 15;89(10):2068-75.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11066047?tool=bestpractice.com

History

Women with a personal and/or family history of certain cancers (e.g., breast cancer, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer) are at increased risk of ovarian cancer; therefore, obtaining a detailed history is important.[15]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no 182: hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Sep;130(3):e110-26.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28832484?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal, endometrial, and gastric [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_2

[35]Kerlikowske K, Brown JS, Grady DG. Should women with familial ovarian cancer undergo prophylactic oophorectomy? Obstet Gynecol. 1992 Oct;80(4):700-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1407898?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Kazerouni N, Greene MH, Lacey JV Jr, et al. Family history of breast cancer as a risk factor for ovarian cancer in a prospective study. Cancer. 2006 Sep 1;107(5):1075-83.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.22082

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16881078?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Ingham SL, Warwick J, Buchan I, et al. Ovarian cancer among 8,005 women from a breast cancer family history clinic: no increased risk of invasive ovarian cancer in families testing negative for BRCA1 and BRCA2. J Med Genet. 2013 Jun;50(6):368-72.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23539753?tool=bestpractice.com

[75]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 716: the role of the obstetrician-gynecologist in the early detection of epithelial ovarian cancer in women at average risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Sep;130(3):e146-9.

https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2017/09000/Committee_Opinion_No__716__The_Role_of_the.47.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28832487?tool=bestpractice.com

[76]Tung N, Ricker C, Messersmith H, et al. Selection of germline genetic testing panels in patients with cancer: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2024 Jul 20;42(21):2599-615.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.24.00662

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38759122?tool=bestpractice.com

Genetic risk evaluation, including counselling and genetic testing, is recommended for women with a blood relative with a known pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in a cancer susceptibility gene or a strong family history of:[16]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal, endometrial, and gastric [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_2

[17]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast, ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_2

[64]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Ovarian cancer: identifying and managing familial and genetic risk. Mar 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng241

[77]Arts-de Jong M, de Bock GH, van Asperen CJ, et al. Germline BRCA1/2 mutation testing is indicated in every patient with epithelial ovarian cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2016 Jul;61:137-45.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27209246?tool=bestpractice.com

[78]Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019 Aug 20;322(7):652-65.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2748515

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31429903?tool=bestpractice.com

[79]Konstantinopoulos PA, Norquist B, Lacchetti C, et al. Germline and somatic tumor testing in epithelial ovarian cancer: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Apr 10;38(11):1222-45.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.19.02960

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31986064?tool=bestpractice.com

[80]Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 727: cascade testing: testing women for known hereditary genetic mutations associated with cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;131(1):e31-4.

https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2018/01000/ACOG_Committee_Opinion_No__727__Cascade_Testing_.40.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29266077?tool=bestpractice.com

Breast and/or ovarian cancer (BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, BRIP1, PALB2, RAD51C, RAD51D)

Colorectal, endometrial, and/or ovarian cancer (Lynch syndrome variants: MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM).

Physical examination

Patients with signs and symptoms suggestive of ovarian cancer should undergo a physical examination of the abdomen and pelvis.

Physical findings are varied and may include ascites, pleural effusion, palpable mass on pelvic examination, and abdominal distension that is dull to percussion. Patients may appear malnourished if they have significant gastrointestinal symptoms. Findings consistent with ascites (e.g., fluid wave, shifting dullness) or with a right-sided pleural effusion (e.g., diminished breath sounds or rales) can often be detected in patients with advanced-stage disease.

On pelvic examination, a mass might be detected in the adnexa (i.e., in the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or surrounding connective tissue) or recto-vaginal space. Referral to a gynaecological oncologist is recommended if a nodular or fixed pelvic mass is detected, or if a patient with an adnexal mass has additional physical examination findings that suggest metastatic disease (e.g., ascites and pleural effusion).[81]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 174 summary: evaluation and management of adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128(5):1193-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27776067?tool=bestpractice.com

Imaging

Transvaginal pelvic ultrasound is the preferred method to evaluate a clinically suspected ovarian mass, providing both qualitative and quantitative information valuable in management.[82]Dodge JE, Covens AL, Lacchetti C, et al. Management of a suspicious adnexal mass: a clinical practice guideline. Curr Oncol. 2012 Aug;19(4):e244-57.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3410836

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22876153?tool=bestpractice.com

[83]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: clinically suspected adnexal mass, no acute symptoms. 2023 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69466/Narrative

Combined transvaginal and transabdominal ultrasound may be useful for assessing larger masses.[83]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: clinically suspected adnexal mass, no acute symptoms. 2023 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69466/Narrative

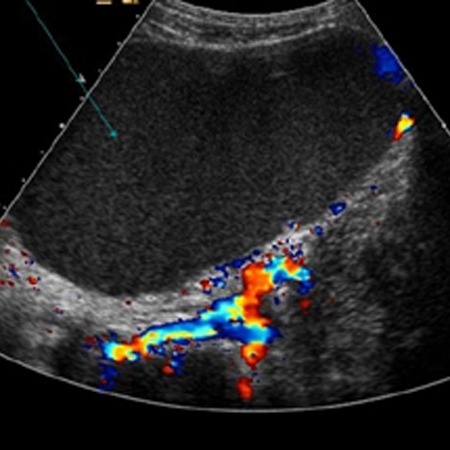

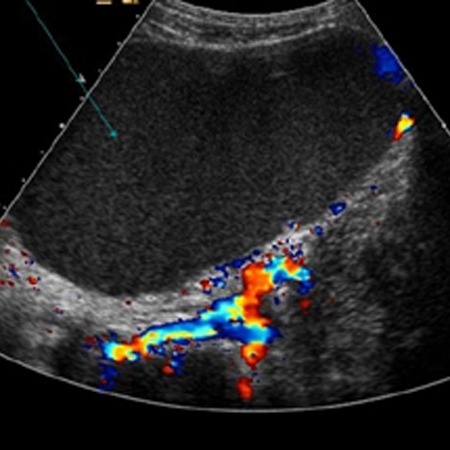

Ultrasound with Doppler imaging can characterise the mass (e.g., cystic, solid, complex), and in most cases can triage the mass into benign or malignant categories.[83]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: clinically suspected adnexal mass, no acute symptoms. 2023 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69466/Narrative

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ovarian cyst with nodules on ultrasoundFrom the collection of Justin C. Chura, MD, Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Philadelphia, PA [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ovarian cyst with normal Doppler flowFrom the collection of Justin C. Chura, MD, Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Philadelphia, PA [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ovarian cyst with normal Doppler flowFrom the collection of Justin C. Chura, MD, Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Philadelphia, PA [Citation ends]. Suspicious masses on ultrasound are typically solid or complex (cystic and solid), septated, and multiloculated, and demonstrate a high blood flow (increased Doppler flow).[84]Karlan BY, Platt LD. The current status of ultrasound and color Doppler imaging in screening for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1994 Dec;55(3 Pt 2):S28-33.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7835806?tool=bestpractice.com

If suspicious findings are discovered on ultrasound, referral to a gynaecological oncologist is recommended.[81]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 174 summary: evaluation and management of adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128(5):1193-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27776067?tool=bestpractice.com

Suspicious masses on ultrasound are typically solid or complex (cystic and solid), septated, and multiloculated, and demonstrate a high blood flow (increased Doppler flow).[84]Karlan BY, Platt LD. The current status of ultrasound and color Doppler imaging in screening for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1994 Dec;55(3 Pt 2):S28-33.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7835806?tool=bestpractice.com

If suspicious findings are discovered on ultrasound, referral to a gynaecological oncologist is recommended.[81]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 174 summary: evaluation and management of adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128(5):1193-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27776067?tool=bestpractice.com

In circumstances where ultrasound cannot adequately characterise an ovarian mass, abdominal/pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without and with gadolinium contrast may provide additional information (e.g., origin of a mass [uterine, ovarian, tubal]) and help determine if the mass is benign or malignant.[83]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: clinically suspected adnexal mass, no acute symptoms. 2023 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69466/Narrative

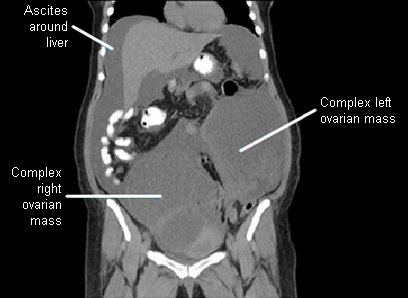

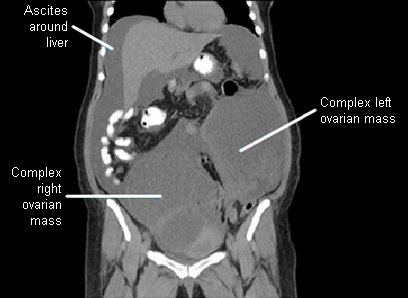

Computed tomography (CT) is less sensitive than ultrasound and MRI in evaluating pelvic organs; therefore, it is not considered part of the standard diagnostic work-up for a pelvic or adnexal mass.[83]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: clinically suspected adnexal mass, no acute symptoms. 2023 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69466/Narrative

CT imaging is mainly used for initial staging of ovarian cancer before initiation of treatment.[85]Kang SK, Reinhold C, Atri M, et al; Expert Panel on Women’s Imaging. ACR appropriateness criteria: staging and follow-up of ovarian cancer. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018 May;15(5s):S198-207.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(18)30343-0/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29724422?tool=bestpractice.com

If suspected on examination, CT imaging of the abdomen, pelvis, or chest can be used to detect the presence of metastatic disease and may guide treatment.[85]Kang SK, Reinhold C, Atri M, et al; Expert Panel on Women’s Imaging. ACR appropriateness criteria: staging and follow-up of ovarian cancer. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018 May;15(5s):S198-207.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(18)30343-0/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29724422?tool=bestpractice.com

[86]Spencer JA. A multidisciplinary approach to ovarian cancer at diagnosis. Br J Radiol. 2005;78 Spec No 2:S94-102.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16306641?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ovarian masses and ascites on coronal CTFrom the collection of Justin C. Chura, MD, Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Philadelphia, PA [Citation ends].

Positron emission tomography (PET), PET-CT, or PET/MRI can be useful for distinguishing between benign and malignant ovarian tumours, but they are not considered part of the standard diagnostic work-up for a pelvic or adnexal mass.[87]Kitajima K, Suzuki K, Senda M, et al. FDG-PET/CT for diagnosis of primary ovarian cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 2011 Jul;32(7):549-53.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21407140?tool=bestpractice.com

[88]Nie J, Zhang J, Gao J, et al. Diagnostic role of 18F-FDG PET/MRI in patients with gynecological malignancies of the pelvis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017 May 8;12(5):e0175401.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0175401

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28481958?tool=bestpractice.com

[89]Tsuyoshi H, Tsujikawa T, Yamada S, et al. Diagnostic value of [18F]FDG PET/MRI for staging in patients with ovarian cancer. EJNMMI Res. 2020 Oct 2;10(1):117.

https://ejnmmires.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s13550-020-00712-3

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33006685?tool=bestpractice.com

Histopathology

If transvaginal ultrasound demonstrates suspicious findings, surgery (laparotomy or laparoscopy) is usually required for definitive histological diagnosis, staging, and tumour debulking (cytoreduction).[90]González-Martín A, Harter P, Leary A, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023 Oct;34(10):833-48.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(23)00797-4/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37597580?tool=bestpractice.com

Surgical staging guides further postoperative treatment, especially for early-stage disease.[19]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: ovarian cancer including fallopian tube cancer and primary peritoneal cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[91]Garcia-Soto AE, Boren T, Wingo SN, et al. Is comprehensive surgical staging needed for thorough evaluation of early-stage ovarian carcinoma? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Mar;206(3):242.e1-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22055337?tool=bestpractice.com

For pre-menopausal patients with a suspicious ovarian mass detected on transvaginal ultrasound, surgery is frequently deferred for 2 to 3 menstrual cycles to establish if the mass is functional or physiological (i.e., not malignant).

Biopsy and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) are not routinely recommended for definitive diagnosis as these procedures can disseminate tumour cells into the peritoneal cavity.[19]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: ovarian cancer including fallopian tube cancer and primary peritoneal cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

They are also prone to sampling error, and may be non-diagnostic. However, for patients unsuitable for surgery, or those with bulky (advanced) disease who are unlikely to achieve complete cytoreduction or optimal (residual disease <1 cm) cytoreduction with surgery, a definitive histological diagnosis should be obtained by core biopsy (or FNA if biopsy is not possible) prior to initiating neoadjuvant chemotherapy.[19]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: ovarian cancer including fallopian tube cancer and primary peritoneal cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[92]Gaillard S, Lacchetti C, Armstrong DK, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed, advanced ovarian cancer: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2025 Mar;43(7):868-91.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO-24-02589

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39841949?tool=bestpractice.com

Laboratory evaluation

Serum CA-125 levels are elevated in >80% of women with advanced-stage disease.[93]Tuxen MK, Sölétormos G, Dombernowsky P. Tumor markers in the management of patients with ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 1995 May;21(3):215-45.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7656266?tool=bestpractice.com

However, this biomarker is not diagnostic because CA-125 levels can be elevated as a result of non-malignant conditions (e.g., endometriosis, uterine fibroids, pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, appendicitis, and ovarian cysts) and other malignant conditions (e.g., pancreatic, breast, lung, gastric, and colon cancers).[66]Cannistra S. Medical progress: cancer of the ovary. N Engl J Med. 2004 Dec 9;351(24):2519-29.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15590954?tool=bestpractice.com

Furthermore, normal CA-125 levels are observed in approximately 50% of patients with early-stage ovarian cancer.[93]Tuxen MK, Sölétormos G, Dombernowsky P. Tumor markers in the management of patients with ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 1995 May;21(3):215-45.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7656266?tool=bestpractice.com

Despite its limitations, it is common practice for clinicians to routinely check CA-125 levels as part of the preoperative evaluation of an adnexal mass. An elevated CA-125 level is more predictive of malignancy in post-menopausal women than in pre-menopausal women.[94]Einhorn N, Sjövall K, Knapp RC, et al. Prospective evaluation of serum CA 125 levels for early detection of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1992 Jul;80(1):14-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1603484?tool=bestpractice.com

In post-menopausal women, a CA-125 level greater than 65 units/mL is reported to have 98% specificity for diagnosing ovarian cancer. In pre-menopausal women CA-125 levels between 35 and 65 units/mL are associated with a 50% to 60% risk of cancer.[94]Einhorn N, Sjövall K, Knapp RC, et al. Prospective evaluation of serum CA 125 levels for early detection of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1992 Jul;80(1):14-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1603484?tool=bestpractice.com

Consultation with a gynaecological oncologist is recommended for post-menopausal women with an elevated CA-125, and for pre-menopausal women with a very elevated CA-125.[81]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 174 summary: evaluation and management of adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128(5):1193-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27776067?tool=bestpractice.com

CA-125 levels are most useful postoperatively once a histological diagnosis of ovarian cancer has been confirmed, where it can be used to monitor treatment response and disease recurrence.[95]Vergote IB, Bormer OP, Abeler VM. Evaluation of serum CA 125 levels in the monitoring of ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987 Jul;157(1):88-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2440307?tool=bestpractice.com

[96]Sölétormos G, Duffy MJ, Othman Abu Hassan S, et al. Clinical use of cancer biomarkers in epithelial ovarian cancer: updated guidelines from the European Group on Tumor Markers. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016 Jan;26(1):43-51.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26588231?tool=bestpractice.com

However, use of CA-125 alone for monitoring and detecting disease recurrence has not been found to improve survival.[97]Rustin GJ, van der Burg ME, Griffin CL, et al; MRC OV05; EORTC 55955 investigators. Early versus delayed treatment of relapsed ovarian cancer (MRC OV05/EORTC 55955): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010 Oct 2;376(9747):1155-63.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(10)61268-8/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20888993?tool=bestpractice.com

In the US, several biomarker tests (OVA1, OVERA, and the risk of ovarian malignancy algorithm [ROMA]) have been approved for determining risk of ovarian cancer in women with an ovarian adnexal mass for which surgery is planned. These tests are not to be used as ovarian cancer screening tools (i.e., prior to detection of an adnexal mass) or as stand-alone diagnostic tests.[19]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: ovarian cancer including fallopian tube cancer and primary peritoneal cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Testing for other tumour biomarkers (e.g. inhibin, alpha-fetoprotein, beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin, lactate dehydrogenase, carcinoembryonic antigen, CA 19-9, and HE4) may be useful in certain circumstances, including the preoperative work-up and monitoring of some less common ovarian cancers.[19]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: ovarian cancer including fallopian tube cancer and primary peritoneal cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Genetic risk evaluation and testing

Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of ovarian cancer should undergo genetic risk evaluation, and germline and somatic genetic testing (e.g., for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, and other ovarian cancer susceptibility genes) if not previously done.[76]Tung N, Ricker C, Messersmith H, et al. Selection of germline genetic testing panels in patients with cancer: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2024 Jul 20;42(21):2599-615.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.24.00662

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38759122?tool=bestpractice.com

[79]Konstantinopoulos PA, Norquist B, Lacchetti C, et al. Germline and somatic tumor testing in epithelial ovarian cancer: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Apr 10;38(11):1222-45.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.19.02960

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31986064?tool=bestpractice.com

[90]González-Martín A, Harter P, Leary A, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023 Oct;34(10):833-48.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(23)00797-4/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37597580?tool=bestpractice.com

Germline testing for a specific pathogenic variant can be carried out, if known; tailored multi-gene panel testing is recommended if the variant is unknown, based on personal and family history.[16]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal, endometrial, and gastric [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_2

[64]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Ovarian cancer: identifying and managing familial and genetic risk. Mar 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng241

[76]Tung N, Ricker C, Messersmith H, et al. Selection of germline genetic testing panels in patients with cancer: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2024 Jul 20;42(21):2599-615.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.24.00662

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38759122?tool=bestpractice.com

BRCA1, BRCA2, and Lynch syndrome genes (MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM) are generally recommended in multi-gene panels for patients with ovarian cancer, with further genes added based on personal and family history.[76]Tung N, Ricker C, Messersmith H, et al. Selection of germline genetic testing panels in patients with cancer: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2024 Jul 20;42(21):2599-615.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.24.00662

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38759122?tool=bestpractice.com

Germline testing should be offered regardless of results from tumour testing.[76]Tung N, Ricker C, Messersmith H, et al. Selection of germline genetic testing panels in patients with cancer: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2024 Jul 20;42(21):2599-615.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.24.00662

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38759122?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ovarian cyst with normal Doppler flowFrom the collection of Justin C. Chura, MD, Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Philadelphia, PA [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ovarian cyst with normal Doppler flowFrom the collection of Justin C. Chura, MD, Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Philadelphia, PA [Citation ends]. Suspicious masses on ultrasound are typically solid or complex (cystic and solid), septated, and multiloculated, and demonstrate a high blood flow (increased Doppler flow).[84] If suspicious findings are discovered on ultrasound, referral to a gynaecological oncologist is recommended.[81]

Suspicious masses on ultrasound are typically solid or complex (cystic and solid), septated, and multiloculated, and demonstrate a high blood flow (increased Doppler flow).[84] If suspicious findings are discovered on ultrasound, referral to a gynaecological oncologist is recommended.[81]