Approach

Milder forms of GN result in an asymptomatic illness. History, clinical examination, and laboratory testing may arouse clinical suspicion of the disease, but a biopsy is sometimes required for definitive diagnosis.

Early diagnosis with specialist referral, kidney biopsy, and serological testing, and early initiation of appropriate therapy are essential to minimise the degree of irreversible kidney injury.

Clinical assessment

Clinical features vary depending on the aetiology, and may include 1 or a combination of haematuria (macroscopic or more commonly microscopic), proteinuria, and oedema (characteristic of nephrotic syndrome). Hypertension may or may not be present; it is uncommon in nephrotic syndrome.

For information on some of the most common causes of nephrotic syndrome (e.g., minimal change disease), see Assessment of nephrotic syndrome (Differentials).

Patients may have features of the underlying disorder, for example:

Joint pain, rash, and haemoptysis in vasculitis[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Palpable purpura on the lower extremities of a child with IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schonlein purpura)From the collection of Dr Paul F. Roberts [Citation ends].

Fever and sore throat in streptococcal infections

Jaundice in hepatitis B and C

Weight loss in malignancies

Stigmata of intravenous drug use.

Laboratory tests

A urinalysis and microscopy of urine sediment are generally the first tests. Further testing is prompted on the basis of the results, together with serum creatinine (measured as part of metabolic profile) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Other initial recommended tests include 24-hour urine collection, full blood count (FBC), and lipid profile.

Urinalysis and renal function tests show haematuria and proteinuria. eGFR and creatinine may be normal or abnormal, and a normal creatinine does not exclude significant renal pathology.

If proteinuria is detected on urinalysis, 24-hour urine collection should be performed as this is the preferred method for quantifying proteinuria in GN.[1] Alternatively, spot urine protein:creatinine ratio (PCR) can be used to estimate 24-hour urinary protein excretion.[1] Patients are classified as having nephrotic-range proteinuria when the 24-hour urine protein excretion is ≥3.5 g per 24 hours or urine PCR is ≥300 mg/mmol (≥3000 mg/g). The presence of hyperlipidaemia, hypoalbuminaemia, and oedema in addition to nephrotic-range proteinuria suggests full nephrotic syndrome.[1]

Haematuria is characterised by dysmorphic red blood cells (RBCs) and formation of RBC casts that are best seen in freshly prepared microscopy of urine sediments, although this is less frequently available as an investigation.

Anaemia, hyperglycaemia (if diabetic), hyperlipidaemia (nephrotic picture), and hypoalbuminaemia (nephrotic picture) may also be evident from the FBC, and from metabolic and lipid profiles.

If urinalysis indicates GN, subsequent tests are ordered to determine the aetiology and hence to guide the treatment. Specific serological testing for systemic causes includes:[1][40][41]

C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Complement

Antinuclear antibody

Rheumatoid factor

Anti-double-stranded DNA

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

Anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies

Antiphospholipase A2 receptor antibodies

Monoclonal protein on serum or urine electrophoresis

Serum free light chains

Antistreptococcal antibodies (antistreptolysin O antibody, anti-DNase B, and antihyaluronidase)

Circulating cryoglobulin

HIV serology, hepatitis B virus serology, hepatitis C virus serology, and drug toxicology screen may also be performed.

The clinical picture guides the need for the appropriate serological testing and a consultation with a kidney disease specialist is recommended.

Imaging

Ultrasound is useful to assess kidney size and eliminate other causes of decreased renal function, such as obstruction.

Chest x-ray is required in rapidly progressive GN to evaluate for pulmonary haemorrhage or granulomas and in nephrotic syndrome to assess for carcinoma or lymphoma.

In older patients computed tomographic scan of chest and abdomen may be important to exclude malignancy.

Kidney biopsy

Patients are referred to a specialist for the decision to biopsy or not, which should be urgently performed if glomerulonephritis is suspected.[17] In some circumstances, treatment may proceed without a kidney biopsy confirmation of diagnosis (e.g., biopsy is contraindicated; biopsy result is unlikely to affect treatment or estimate of prognosis; to avoid delaying treatment in patients with rapidly progressive disease).[1][40][42]

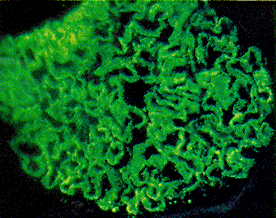

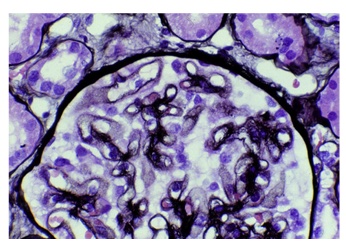

Kidney biopsy (with light, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy) remains the most sensitive and specific test for definitive diagnosis of GN for patients with nephrotic and nephritic syndromes and rapidly progressive GN.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Minimal change nephropathy: the glomerulus has a normal appearanceFrom: Mason PD, Musey CD. BMJ. 1994 Dec 10;309(6968):1557-63 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis showing (left) thickened capillary loops with diffuse cellular proliferation, giving characteristic 'lobular' appearance (light microscopy; stains: haematoxylin and eosin) and (right) coarse patchy granular immunofluorescent staining of IgM along capillary loopsFrom: Mason PD, Musey CD. BMJ. 1994 Dec 10;309(6968):1557-63 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis showing (left) thickened capillary loops with diffuse cellular proliferation, giving characteristic 'lobular' appearance (light microscopy; stains: haematoxylin and eosin) and (right) coarse patchy granular immunofluorescent staining of IgM along capillary loopsFrom: Mason PD, Musey CD. BMJ. 1994 Dec 10;309(6968):1557-63 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Membranous nephropathy showing fine granular immunofluorescent staining of IgG along basement membraneMason PD, Musey CD. BMJ. 1994 Dec 10;309(6968):1557-63 [Citation ends].

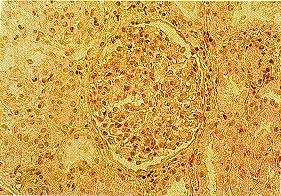

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Membranous nephropathy showing fine granular immunofluorescent staining of IgG along basement membraneMason PD, Musey CD. BMJ. 1994 Dec 10;309(6968):1557-63 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Membranous nephropathy shows slightly prominent capillary walls that appear more rigid than normal; however, deposits cannot be directly visualised (light microscopy; periodic acid Schiff stain)Fogo AB, Lusco MA, Najafian B, et al. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(3):e15-7 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Membranous nephropathy shows slightly prominent capillary walls that appear more rigid than normal; however, deposits cannot be directly visualised (light microscopy; periodic acid Schiff stain)Fogo AB, Lusco MA, Najafian B, et al. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(3):e15-7 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Membranous nephropathy with thickened capillary walls with the appearance of numerous pinpoint 'holes' in tangential sections, indicating deposits that did not stain (light microscopy; Jones silver stain)Fogo AB, Lusco MA, Najafian B, et al. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(3):e15-7 [Citation ends].

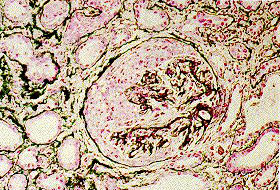

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Membranous nephropathy with thickened capillary walls with the appearance of numerous pinpoint 'holes' in tangential sections, indicating deposits that did not stain (light microscopy; Jones silver stain)Fogo AB, Lusco MA, Najafian B, et al. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(3):e15-7 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis as seen in poststreptococcal glomerulonephritisFrom: Mason PD, Musey CD. BMJ. 1994 Dec 10;309(6968):1557-63 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis as seen in poststreptococcal glomerulonephritisFrom: Mason PD, Musey CD. BMJ. 1994 Dec 10;309(6968):1557-63 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Crescentic glomerulonephritis with cellular crescent occupying large portion Bowman's capsule and compressing glomerular tuftFrom: Mason PD, Musey CD. BMJ. 1994 Dec 10;309(6968):1557-63 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Crescentic glomerulonephritis with cellular crescent occupying large portion Bowman's capsule and compressing glomerular tuftFrom: Mason PD, Musey CD. BMJ. 1994 Dec 10;309(6968):1557-63 [Citation ends].

However, a kidney biopsy is not always performed for syndromes of isolated haematuria, haematuria plus low-level proteinuria, and low-grade isolated proteinuria (less than 1 g per 24 hours).[42] Some systemic diseases may not require a kidney biopsy to establish the diagnosis: (e.g., post-infectious GN), although biopsy may give prognostic information. In some systemic diseases, biopsy of other sites (such as fat pad biopsy for amyloidosis, lung for granulomatosis with polyangiitis) can be performed.[43]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer