History

A phaeochromocytoma should be suspected in any patient who presents with the classic triad of symptoms:[1]Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 8;381(6):552-65.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31390501?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Martucci VL, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: diagnosis, genetics, management, and treatment. Curr Probl Cancer. 2014 Jan-Feb;38(1):7-41.

https://www.cpcancer.com/article/S0147-0272(14)00002-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24636754?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Palpitations

Headaches

Diaphoresis.

Episodic spells of the symptoms are characteristic and they can vary in duration from seconds to hours and typically get worse with time as the tumour enlarges.

Other suggestive features:

Enquiring about the family history is vital. Up to 40% of phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PPGL) cases are a manifestation of a hereditary syndrome (e.g., multiple endocrine neoplasia [MEN] syndrome type 2A and B; Von Hippel-Lindau [VHL] disease; neurofibromatosis type 1 [NF1]).[1]Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 8;381(6):552-65.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31390501?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Martucci VL, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: diagnosis, genetics, management, and treatment. Curr Probl Cancer. 2014 Jan-Feb;38(1):7-41.

https://www.cpcancer.com/article/S0147-0272(14)00002-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24636754?tool=bestpractice.com

Germline mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase [SDH] subunit B, C, and D genes, or a personal history of a phaeochromocytoma, increase risk.[35]Amar L, Pacak K, Steichen O, et al. International consensus on initial screening and follow-up of asymptomatic SDHx mutation carriers. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021 Jul;17(7):435-44.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41574-021-00492-3

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34021277?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Andrews KA, Ascher DB, Pires DEV, et al. Tumour risks and genotype-phenotype correlations associated with germline variants in succinate dehydrogenase subunit genes SDHB, SDHC and SDHD. J Med Genet. 2018 Jun;55(6):384-94.

https://jmg.bmj.com/content/55/6/384

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29386252?tool=bestpractice.com

Clinical presentation of phaeochromocytoma can vary widely and 10% to 15% of cases can be completely asymptomatic with the tumour discovered incidentally during abdominal investigation for other reasons.[44]Rogowski-Lehmann N, Geroula A, Prejbisz A, et al. Missed clinical clues in patients with pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma discovered by imaging. Endocr Connect. 2018 Sep 1 [Epub ahead of print].

https://www.doi.org/10.1530/EC-18-0318

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30352425?tool=bestpractice.com

Approximately 3% to 7% of incidentally discovered adrenal masses are diagnosed as phaeochromocytoma.[44]Rogowski-Lehmann N, Geroula A, Prejbisz A, et al. Missed clinical clues in patients with pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma discovered by imaging. Endocr Connect. 2018 Sep 1 [Epub ahead of print].

https://www.doi.org/10.1530/EC-18-0318

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30352425?tool=bestpractice.com

It is recommended that all patients with such masses should undergo biochemical evaluation.[45]Fassnacht M, Arlt W, Bancos I, et al. Management of adrenal incidentalomas: European Society of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline in collaboration with the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016 Aug;175(2):G1-G34.

https://www.doi.org/10.1530/EJE-16-0467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27390021?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Zeiger MA, Thompson GB, Duh QY, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Association of Endocrine Surgeons medical guidelines for the management of adrenal incidentalomas: executive summary of recommendations. Endocr Pract. 2009 Jul-Aug;15(5):450-3.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19632968?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical examination findings

Hypertension is the principal sign on examination.[47]Zuber SM, Kantorovich V, Pacak K. Hypertension in pheochromocytoma: characteristics and treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011 Jun;40(2):295-311.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21565668?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients often present with accelerated hypertension or hypertension refractory to multiple drug regimens. In about 48% of cases the hypertension is paroxysmal or labile in nature.[47]Zuber SM, Kantorovich V, Pacak K. Hypertension in pheochromocytoma: characteristics and treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011 Jun;40(2):295-311.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21565668?tool=bestpractice.com

Phaeochromocytomas may present with life-threatening acute hypertensive emergencies (e.g., encephalopathy), as well as clinical consequences of long-lasting hypertension (e.g., hypertensive retinopathy, proteinuria, cardiomyopathies, or arrhythmias).[47]Zuber SM, Kantorovich V, Pacak K. Hypertension in pheochromocytoma: characteristics and treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011 Jun;40(2):295-311.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21565668?tool=bestpractice.com

A hypertensive crisis can be triggered by medicines, intravenous contrast, surgery, or even exercise. Postural hypotension may be a feature due to volume contraction. Other signs associated with phaeochromocytomas include abdominal masses, tachycardia, pallor, or tremors.[1]Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 8;381(6):552-65.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31390501?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Martucci VL, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: diagnosis, genetics, management, and treatment. Curr Probl Cancer. 2014 Jan-Feb;38(1):7-41.

https://www.cpcancer.com/article/S0147-0272(14)00002-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24636754?tool=bestpractice.com

Laboratory evaluation

All patients with palpitations, headaches, and diaphoresis should be investigated, whether they have hypertension or not.[27]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

Investigations should be carried out in any patient with hereditary risk that predisposes to phaeochromocytoma development, such as MEN2.[27]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

Biochemical tests

Measurement of plasma free metanephrines (also known as metadrenalines), or 24-hour urine fractionated metanephrines and normetanephrines (also known as normetadrenaline), is recommended in patients with suspected phaeochromocytoma.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

[27]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Elevations 3 times above the upper limit of normal are diagnostic.[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Blood sampling should be performed in the supine position.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

[26]Granberg D, Juhlin CC, Falhammar H. Metastatic pheochromocytomas and abdominal paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Apr 23;106(5):e1937-52.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8063253

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33462603?tool=bestpractice.com

Some drugs may interfere with testing results (e.g., buspirone, cocaine, labetalol, levodopa, methyldopa, monoamine oxidase inhibitors [MAOIs], paracetamol, phenoxybenzamine, sotalol, sulfasalazine, sympathomimetics, tricyclic antidepressants); review patient medications accordingly.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Note that urine or plasma catecholamines are no longer routinely recommended for the evaluation of phaeochromocytoma.[27]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

A clonidine suppression test can be used to discriminate patients with mildly elevated test results for plasma normetanephrine (attributable to increased sympathetic activity) from those with elevated test results due to a PPGL.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

Chromogranin A may be elevated in patients with a neuroendocrine tumour; chromogranin A plus urinary fractionated metanephrines have been suggested as follow-up tests for elevations of plasma metanephrines.[48]Algeciras-Schimnich A, Preissner CM, Young WF Jr, et al. Plasma chromogranin A or urine fractionated metanephrines follow-up testing improves the diagnostic accuracy of plasma fractionated metanephrines for pheochromocytoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Jan;93(1):91-5.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2729153

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17940110?tool=bestpractice.com

Imaging studies

Localisation studies should only be undertaken after a biochemical abnormality is demonstrated.

CT imaging is recommended given its excellent spatial resolution in the abdomen; MRI is an option for patients in whom CT imaging is contraindicated.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]Chen H, Sippel RS, O'Dorisio MS, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guideline for the diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors: pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma, and medullary thyroid cancer. Pancreas. 2010 Aug;39(6):775-83.

https://www.doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ebb4f0

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20664475?tool=bestpractice.com

Multiphasic abdomen/pelvis CT or MRI, 18F-fluoro-2 deoxy-D-glucose (18F-FDG) PET/CT, or I-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy are performed, as appropriate, in the presence of metastatic or multifocal disease.[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

18F-FDG PET/CT is preferred to MIBG scintigraphy in this scenario.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

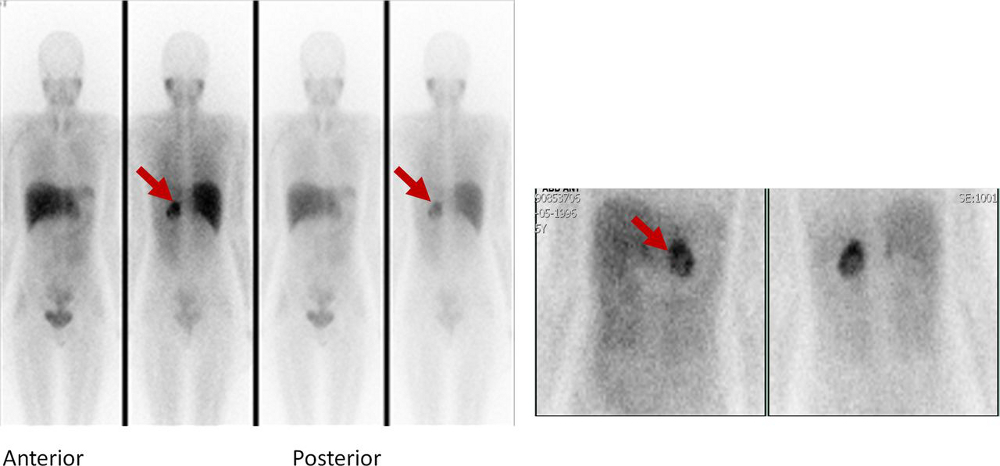

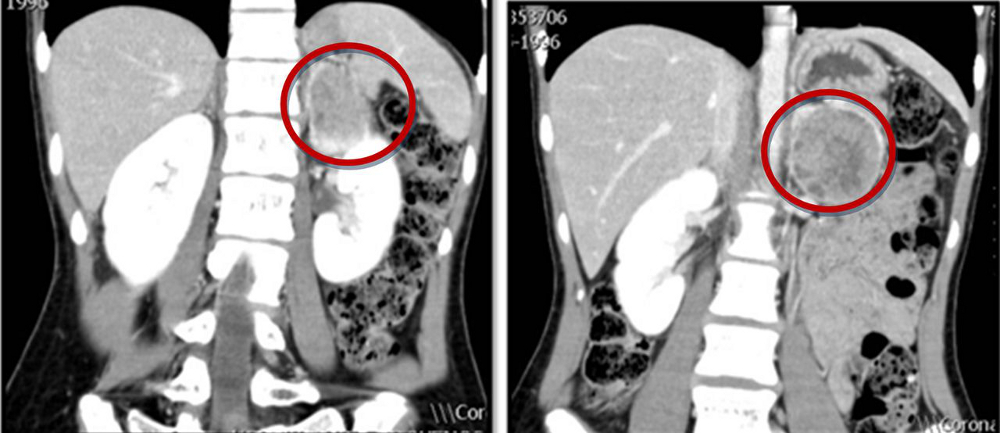

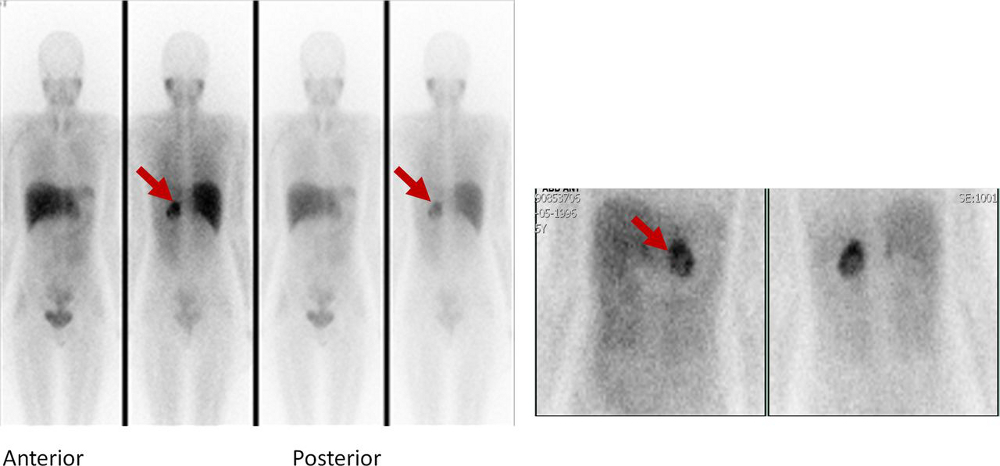

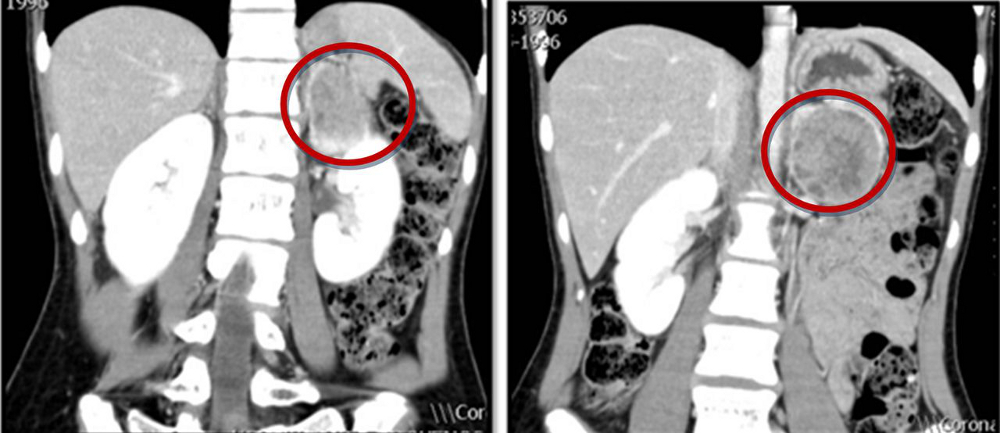

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal CT scan with mass in the left adrenal gland, compatible with a phaeochromocytomaAlface MM et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Aug 4;2015:bcr2015211184; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy identified hyperfixation in the left adrenal gland compatible with phaeochromocytomaAlface MM et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Aug 4;2015:bcr2015211184; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy identified hyperfixation in the left adrenal gland compatible with phaeochromocytomaAlface MM et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Aug 4;2015:bcr2015211184; used with permission [Citation ends].

Genetic testing

All patients with phaeochromocytomas should undergo genetic testing to identify potential hereditary tumour disorders that would necessitate more detailed evaluation and follow-up.[1]Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 8;381(6):552-65.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31390501?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Patient engagement in a shared decision-making process is essential.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Genetic testing may be considered in patients with phaeochromocytoma with:[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

Positive family history (premised upon pedigree or identification of a PPGL-susceptibility gene mutation)

Syndromic features

Multifocal, bilateral, or metastatic disease

Targeted germline mutation testing (e.g, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 [MEN2], Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome [VHL], and neurofibromatosis type 1 [NF1]) is recommended in patients with positive family history or syndromic presentation.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with metastatic disease should undergo testing for SDHB mutations.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy identified hyperfixation in the left adrenal gland compatible with phaeochromocytomaAlface MM et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Aug 4;2015:bcr2015211184; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy identified hyperfixation in the left adrenal gland compatible with phaeochromocytomaAlface MM et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Aug 4;2015:bcr2015211184; used with permission [Citation ends].