As neuroblastoma can occur anywhere along the sympathetic nervous system, signs and symptoms depend on the location of the original tumour and any sites of metastases.

The tumour's ability to metabolise catecholamines may also contribute to symptomatology.

Diagnosis is confirmed by unequivocal histology from tumour tissue by light microscopy, or by unequivocal evidence of neuroblastoma cells on bone marrow aspiration and biopsy in the setting of increased urine catecholamines.[27]Brodeur GM, Pritchard J, Berthold F, et al. Revisions of the international criteria for neuroblastoma diagnosis, staging, and response to treatment. J Clin Oncol. 1993 Aug;11(8):1466-77.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8336186?tool=bestpractice.com

History

The vast majority of neuroblastomas are diagnosed in children younger than 5 years of age, and nearly all patients are diagnosed by the time they are 10 years of age.

ACS: key statistics about neuroblastoma

Opens in new window The median age at diagnosis is 17 months.[12]Campbell K, Siegel DA, Umaretiya PJ, et al. A comprehensive analysis of neuroblastoma incidence, survival, and racial and ethnic disparities from 2001 to 2019. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2024 Jan;71(1):e30732.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11018254

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37867409?tool=bestpractice.com

A family history of neuroblastic tumours may be present 1% to 2% of patients.[13]Kamihara J, Diller LR, Foulkes WD, et al. Neuroblastoma predisposition and surveillance - an update from the 2023 AACR Childhood Cancer Predisposition Workshop. Clin Cancer Res. 2024 Aug 1;30(15):3137-43.

https://aacrjournals.org/clincancerres/article/30/15/3137/746580/Neuroblastoma-Predisposition-and-Surveillance-An

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38860978?tool=bestpractice.com

A few medical conditions, some of which are related to aberrant neural crest development, predispose a patient to developing neuroblastoma, including Turner syndrome, Hirschsprung's disease, congenital central hypoventilation syndrome, and neurofibromatosis type 1.[17]Barr EK, Applebaum MA. Genetic predisposition to neuroblastoma. Children (Basel). 2018 Aug 31;5(9):119.

https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9067/5/9/119

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30200332?tool=bestpractice.com

[28]Kamihara J, Bourdeaut F, Foulkes WD, et al. Retinoblastoma and Neuroblastoma Predisposition and Surveillance. Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Jul 1;23(13):e98-e106.

https://www.doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0652

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28674118?tool=bestpractice.com

Presenting symptoms can be a direct result of mass effect of the primary lesion (e.g., constipation, abdominal distention) or the result of metastases (e.g., bone pain); however, patients with localised disease may be asymptomatic.

Abdominal distention (caused by the presence of a large abdominal mass) is the most common symptom.[29]Granja C, Mota L. Paediatric neuroblastoma presenting as an asymptomatic abdominal mass: a report on the importance of a complete clinical examination with a view to a timely diagnosis and therapeutic guidance in paediatric oncology. BMJ Case Rep. 2022 May 19;15(5):e247907.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9121434

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35589269?tool=bestpractice.com

[30]Chu CM, Rasalkar DD, Hu YJ, et al. Clinical presentations and imaging findings of neuroblastoma beyond abdominal mass and a review of imaging algorithm. Br J Radiol. 2011 Jan;84(997):81-91.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3473807

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21172969?tool=bestpractice.com

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend very urgent referral (an appointment within 48 hours) for specialist assessment for neuroblastoma in children with a palpable abdominal mass or an unexplained enlarged abdominal organ.[31]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. NICE guideline NG12. Oct 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12

Constipation, usually secondary to the mass effect of an abdominal tumour, is also a common presenting symptom. Patients with tumour secretion of vasoactive intestinal protein (VIP), a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with neuroblastoma, may present with intractable secretory diarrhoea, although this is uncommon.[9]Kaplan SJ, Holbrook CT, McDaniel HG, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide secreting tumors of childhood. Am J Dis Child. 1980 Jan;134(1):21-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6101297?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients (or carer) commonly report general systemic symptoms such as decreased appetite, weight loss, fussiness (in infants), fatigue, or abdominal, bone, or back pain. These symptoms may indicate metastatic spread.

Clinical presentation may differ between infants and older children. Infants may sometimes present with either an asymptomatic adrenal mass detected on routine prenatal ultrasound, or in the case of patients <18 months with stage MS disease (International Neuroblastoma Risk Group Staging System), severe hepatomegaly secondary to liver metastases.[2]Brisse HJ, McCarville MB, Granata C, et al. Guidelines for imaging and staging of neuroblastic tumors: consensus report from the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group Project. Radiology. 2011 Oct;261(1):243-57.

http://pubs.rsna.org/doi/full/10.1148/radiol.11101352

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21586679?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Raitio A, Rice MJ, Mullassery D, et al. Stage 4S Neuroblastoma: what are the outcomes? A systematic review of published studies. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2021 Oct;31(5):385-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32932540?tool=bestpractice.com

Skin nodules are also more common in infants compared with older children.

Physical examination

Presenting signs will depend on the location of the primary lesion and the presence of any metastases. A large abdominal mass is commonly felt on palpation of the abdomen.[29]Granja C, Mota L. Paediatric neuroblastoma presenting as an asymptomatic abdominal mass: a report on the importance of a complete clinical examination with a view to a timely diagnosis and therapeutic guidance in paediatric oncology. BMJ Case Rep. 2022 May 19;15(5):e247907.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9121434

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35589269?tool=bestpractice.com

[30]Chu CM, Rasalkar DD, Hu YJ, et al. Clinical presentations and imaging findings of neuroblastoma beyond abdominal mass and a review of imaging algorithm. Br J Radiol. 2011 Jan;84(997):81-91.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3473807

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21172969?tool=bestpractice.com

If the primary lesion is in the upper portion of the thoracic outlet or cervical sympathetic chain, patients will often present with:[1]Brodeur G, Hogarty M, Bagatell R, et al. Neuroblastoma. In: Pizzo P, Poplack D, eds. Principles and practice of pediatric oncology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2016:772.[5]Pollard ZF, Greenberg MF, Bordenca M, et al. Atypical acquired pediatric Horner syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010 Jul;128(7):937-40.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaophthalmology/fullarticle/426070

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20625060?tool=bestpractice.com

[6]Ogita S, Tokiwa K, Takahashi T, et al. Congenital cervical neuroblastoma associated with Horner syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 1988 Nov;23(11):991-2.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3244095?tool=bestpractice.com

or

Superior vena cava syndrome (characterised by dyspnoea, facial swelling, cough, distended neck/chest veins, oedema of the upper extremities) due to mass effect on the vascular system

If the tumour extends into the spinal canal, patients may initially present with signs of spinal cord compression including loss of bowel and bladder function, lower-extremity weakness, and back pain.

Hypertension may be present, but is uncommon. It occurs due to mass effect of an abdominal tumour, which may compromise renal vasculature resulting in alterations of the renin-activating system pathway, or may be a result of tumour-associated catecholamine secretion.[1]Brodeur G, Hogarty M, Bagatell R, et al. Neuroblastoma. In: Pizzo P, Poplack D, eds. Principles and practice of pediatric oncology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2016:772.[25]Harding M, Deyell RJ, Blydt-Hansen T. Catecholamines in neuroblastoma: driver of hypertension, or solely a marker of disease? Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2022 Aug;5(8):e1569.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9351666

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34612613?tool=bestpractice.com

Opsoclonus-myoclonus ataxia (OMA; also known as opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome), a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with neuroblastoma, occurs in <3% of patients with neuroblastoma.[33]Rudnick E, Khakoo Y, Antunes NL, et al. Opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome in neuroblastoma: clinical outcome and antineuronal antibodies-a report from the Children's Cancer Group Study. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001 Jun;36(6):612-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11344492?tool=bestpractice.com

In patients with OMA, nearly one half will be diagnosed with neuroblastoma; therefore, all children with OMA should be evaluated for neuroblastoma.[34]Rossor T, Yeh EA, Khakoo Y, et al. Diagnosis and management of opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome in children: an international perspective. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022 May;9(3):e1153.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8906188

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35260471?tool=bestpractice.com

Rapid, dancing eye movements, rhythmic jerking of limbs/trunk, and ataxia are pathognomonic for OMA.[8]Brunklaus A, Pohl K, Zuberi SM, et al. Investigating neuroblastoma in childhood opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 2012 May;97(5):461-3.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21460401?tool=bestpractice.com

Signs of metastatic spread may be evident on examination

Specific signs will depend on the location of the metastases, the most common sites being lymph nodes, bone marrow, bone, liver, skin, orbits, and dura. Patients with orbital metastases may present with periorbital ecchymosis (commonly referred to as panda eyes). Palpable subcutaneous skin nodules are another common sign associated with metastatic spread, but occur mainly in infants.[35]El-Enany G, Nagui NA, Hilal RF. Stage IV adrenal neuroblastoma with subcutaneous nodules in an infant: a case report. Int J Dermatol. 2020 Aug;59(8):e274-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32368803?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Kazanowska B, Reich A, Jelen M, et al. Chronic metastatic neuroblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008 Apr;50(4):898-900.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17914736?tool=bestpractice.com

If the disease has spread to the bone marrow, pallor, infections, and bleeding may be present as a result of pancytopenia. Hepatomegaly may be noted with metastatic spread to the liver.

Initial investigations

Initial investigations for all patients with suspected neuroblastoma include a full blood count, serum electrolytes, renal function, and liver function tests. Lactate dehydrogenase may be considered.[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Neuroblastoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Because neuroblastoma arises from the sympathetic nervous system, specific tests to look for the presence of catecholamine metabolism may form part of the initial work-up.[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Neuroblastoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Testing for the catecholamine degradation products, homovanillic acid (HVA) and vanillylmandelic acid (VMA), is required for diagnosis if bone marrow is the only diagnostic tissue obtained. HVA and VMA are secreted by the majority of tumours and can be detected in the patient's urine.[26]Barco S, Gennai I, Reggiardo G, et al. Urinary homovanillic and vanillylmandelic acid in the diagnosis of neuroblastoma: report from the Italian Cooperative Group for Neuroblastoma. Clin Biochem. 2014 Jun;47(9):848-52.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24769278?tool=bestpractice.com

This test is highly sensitive and specific for neuroblastoma.

Urinary catecholamine levels are no longer recommended for the assessment of treatment response (due to influence of diet and lack of standardisation).[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Neuroblastoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[38]Park JR, Bagatell R, Cohn SL, et al. Revisions to the International Neuroblastoma Response Criteria: a consensus statement from the National Cancer Institute Clinical Trials Planning Meeting. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Aug 1;35(22):2580-7.

http://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2016.72.0177?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28471719?tool=bestpractice.com

Initial imaging studies

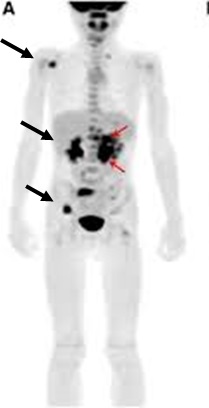

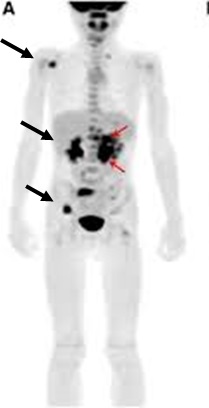

Ultrasound of the abdomen should form part of the work-up in all patients with suspected neuroblastoma. If a mass is detected on ultrasound, further imaging should include a computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the abdomen, and may reveal a heterogeneous mass (possibly with calcifications). If there is intraspinal extension of the tumour, MRI is preferred over CT.[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Neuroblastoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the abdomen showing paraspinal neuroblastomaFrom the personal collection of Dr Jason Shohet [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing a thoracic paraspinal neuroblastoma wrapping around the spineFrom the personal collection of Dr Jason Shohet [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing a thoracic paraspinal neuroblastoma wrapping around the spineFrom the personal collection of Dr Jason Shohet [Citation ends].

Guidelines recommend biopsy for most patients if upfront resection is not indicated.[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Neuroblastoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

The tissue sample may be obtained by percutaneous needle or incisional biopsy of the primary tumour, or bone marrow aspiration and biopsy if bone marrow metastasis is suspected.[39]Campagna G, Rosenfeld E, Foster J, et al. Evolving biopsy techniques for the diagnosis of neuroblastoma in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2018 Nov;53(11):2235-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29753525?tool=bestpractice.com

Definitive diagnosis requires one of the following:[27]Brodeur GM, Pritchard J, Berthold F, et al. Revisions of the international criteria for neuroblastoma diagnosis, staging, and response to treatment. J Clin Oncol. 1993 Aug;11(8):1466-77.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8336186?tool=bestpractice.com

Unequivocal histological diagnosis from tumour tissue by light microscopy.

Unequivocal evidence of neuroblastoma cells on bone marrow aspiration and biopsy in the setting of increased urine catecholamines.

Evaluation of tumour tissue

Key for risk stratification. Amplification of v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene neuroblastoma-derived homolog (MYCN) is associated with aggressive (high-risk) disease. Therefore, tumour tissue must be evaluated for MYCN.[40]Bartolucci D, Montemurro L, Raieli S, et al. MYCN impact on high-risk neuroblastoma: from diagnosis and prognosis to targeted treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Sep 12;14(18):4421.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9496712

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36139583?tool=bestpractice.com

Segmental chromosomal aberrations may be associated with aggressive disease (depending upon other factors).[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Neuroblastoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Evaluation of DNA ploidy may be required to guide treatment duration. Bilateral bone marrow aspirates and trephine biopsies may be of diagnostic value when, in rare cases, marrow is the only source of tumour material.[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Neuroblastoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Investigations for metastatic disease

Neuroblastoma commonly presents with metastases. As such, a comprehensive evaluation for metastases is recommended in all patients for whom there is a high suspicion for neuroblastoma, or in patients who have been diagnosed with neuroblastoma.

123-Iodine-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy is recommended for the assessment of metastatic disease.[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Neuroblastoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Thyroid protection with potassium iodide should be given prior to all MIBG infusions, whether therapeutic or diagnostic.[41]Agrawal A, Rangarajan V, Shah S, et al. MIBG (metaiodobenzylguanidine) theranostics in pediatric and adult malignancies. Br J Radiol. 2018 Nov;91(1091):20180103.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6475939

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30048149?tool=bestpractice.com

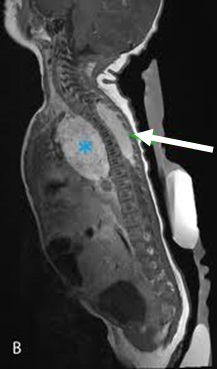

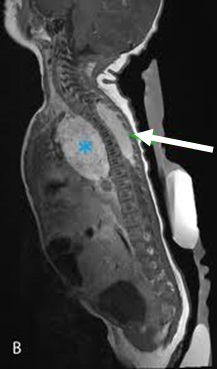

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: 123-iodine-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy showing multifocal bony metastasesFrom the personal collection of Dr Jason Shohet [Citation ends].

18-Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET should be obtained in the absence of 123-I-MIBG uptake or in patients with suspected mixed-avidity disease.[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Neuroblastoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Staging

In order to standardise staging internationally, irrespective of surgery, the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) developed a staging system based on image-defined risk factors (IDRFs).[2]Brisse HJ, McCarville MB, Granata C, et al. Guidelines for imaging and staging of neuroblastic tumors: consensus report from the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group Project. Radiology. 2011 Oct;261(1):243-57.

http://pubs.rsna.org/doi/full/10.1148/radiol.11101352

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21586679?tool=bestpractice.com

IDRFs are determined at the time of diagnosis, prior to surgery.

See the Diagnostic criteria section for further detail on the various staging systems.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing a thoracic paraspinal neuroblastoma wrapping around the spineFrom the personal collection of Dr Jason Shohet [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing a thoracic paraspinal neuroblastoma wrapping around the spineFrom the personal collection of Dr Jason Shohet [Citation ends].