Approach

The main presenting symptoms include headache and incidental papilloedema.[34] There is no evidence of deformity or obstruction of the ventricular system, and neurodiagnostic studies are otherwise normal except for increased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure. No secondary cause of intracranial hypertension is apparent.

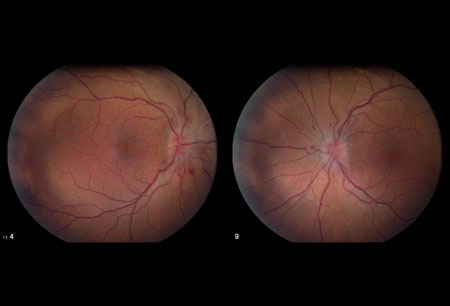

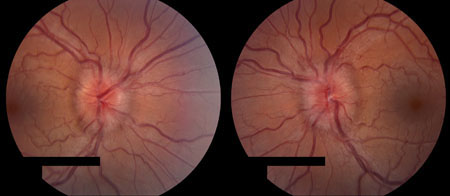

Signs that may be found on examination include optic disc swelling, sixth nerve paresis, and disturbances in sensory visual function. Visual field loss is ubiquitous, and the prototype pattern for early loss is enlargement of the blind spot and inferonasal loss.[35] The modified Dandy criteria can be used as diagnostic criteria.[36][37][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral disc oedemaFrom the personal collection of Dr M. Wall; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral disc swelling settledFrom the personal collection of Dr M. Wall; used with permission [Citation ends].

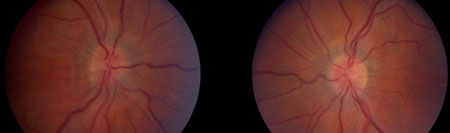

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral disc swelling settledFrom the personal collection of Dr M. Wall; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral optic atrophyFrom the personal collection of Dr M. Wall; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral optic atrophyFrom the personal collection of Dr M. Wall; used with permission [Citation ends].

History

History of the following conditions should be considered, as they are likely causes of intracranial hypertension that may otherwise meet the Dandy criteria for IIH:

Decreased flow through arachnoid granulations: scarring from previous inflammation (e.g., meningitis, sequel to subarachnoid haemorrhage)

Obstruction to venous drainage: venous sinus thromboses (hypercoagulable states, contiguous infection, e.g., middle ear or mastoid-otitic hydrocephalus), bilateral radical neck dissections, superior vena cava syndrome, increased right heart pressure

Endocrine disorders: Addison's disease, hypoparathyroidism, corticosteroid withdrawal

Nutritional disorders: hypervitaminosis A (vitamin, liver, or isotretinoin intake), hyperalimentation in psychosocial short stature

Arteriovenous malformations and dural shunts.

Further probable causes should also be enquired about if a history for the likely causes is negative:

Anabolic steroids (may cause venous sinus thrombosis)

Chlordecone (also known as kepone, an insecticide)

Ketoprofen or indometacin (indomethacin) (in Bartter's syndrome)

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Thyroid replacement therapy in hypothyroid children

Uraemia

Tetracycline use

Use of all-trans retinoic acid

Amiodarone use

Iron-deficiency anaemia

Lithium carbonate use

Nalidixic acid use.

Clinical features

Patients may present with headache, incidental papilloedema, diplopia, nausea or vomiting, neck or back pain, pulsatile tinnitus, retrobulbar pain, transient visual obscurations, and other visual symptoms.[34][38] Most of these symptoms alone are not diagnostic for IIH. Pulsatile tinnitus is a relatively specific symptom for elevated intracranial pressure, especially if associated with the onset of other symptoms of IIH.

Headache

Present in almost all patients and is the usual presenting symptom. In one study, the most common headache phenotypes were migraine (52%), tension-type headache (22%), probable migraine (16%), and probable tension-type headache (4%).[39] The pain may be pressure-like or throbbing, and is often reported as disabling.[39][40] Many patients have mixed headache syndromes that include migraine and medication-overuse headaches. Nausea is reported in almost half of patients but vomiting is less common.[39]

Transient visual obscurations

Episodes of visual loss that usually last for <30 seconds and are followed by full restoration of vision. Visual obscurations occur in 68% of patients.[31] The episodes may be monocular or binocular. The cause of these episodes is thought to be transient ischaemia of the optic nerve head, caused by increased tissue pressure.[41] One study found frequent transient visual obscurations (more than one per day) to be a risk factor for poor visual outcome.[42]

Pulse-synchronous tinnitus

Occurs in approximately 52% of patients.[31] The sound is bilateral in two-thirds of patients and unilateral in one third.[31] In patients with intracranial hypertension, jugular compression ipsilateral to the sound abolishes it.[43] The sound is thought to be due to transmission of intensified vascular pulsations, via transverse venous sinus stenoses (creating flow turbulence) that can be seen with venography. It is a relatively specific symptom of increased intracranial pressure.

Ocular motility disturbances

Horizontal diplopia occurs in about 33% of patients, and documented sixth cranial nerve palsy/palsies occur in 10% to 20%.[38] Ocular motility disturbances other than sixth cranial nerve palsies are very rare, and if present suggest either a vertical ocular motor imbalance associated with the sixth nerve palsy or a diagnosis other than IIH.[1]

Visual examination and investigations

Papilloedema is the cardinal sign of IIH, but must be differentiated from pseudopapilloedema. The following should be recorded once papilloedema is confirmed.

Eye examination: to assess for relative afferent pupillary defect or ocular motility disturbances, including sixth cranial nerve paresis.

Visual acuity: usually normal, or near normal, in patients with papilloedema, except when the condition is long-standing and severe, or if there is a neurosensory detachment.

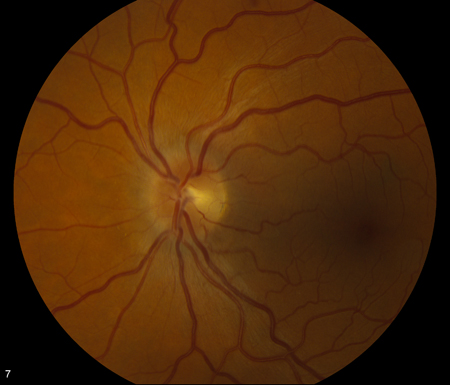

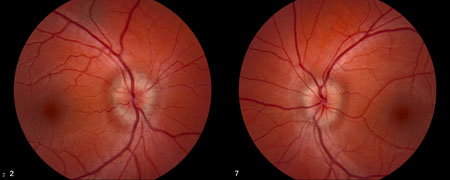

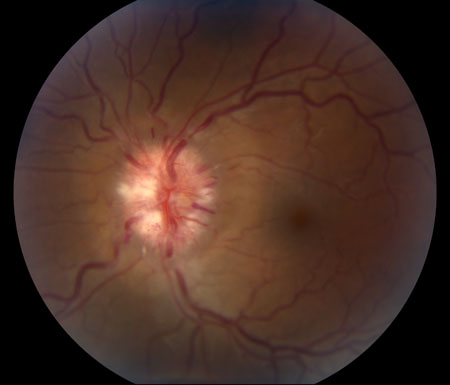

Dilated fundoscopy: to grade the papilloedema. In general, the higher the grade of papilloedema, the worse the visual outcome.[15] However, the severity of visual loss cannot easily be predicted from the severity of the papilloedema. Severity of disc swelling is graded according to the Modified Frisén Scale.[37][44][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Frisén stage 1From the personal collection of Dr M. Wall; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Frisén stage 2From the personal collection of Dr M. Wall; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Frisén stage 2From the personal collection of Dr M. Wall; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Frisén stage 3From the personal collection of Dr M. Wall; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Frisén stage 3From the personal collection of Dr M. Wall; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Frisén stage 4From the personal collection of Dr M. Wall; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Frisén stage 4From the personal collection of Dr M. Wall; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Frisén stage 5From the personal collection of Dr M. Wall; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Frisén stage 5From the personal collection of Dr M. Wall; used with permission [Citation ends]. Nerve fibre layer haemorrhages are associated with a higher grade of papilloedema and are present in about one third of patients at presentation.[45]

Nerve fibre layer haemorrhages are associated with a higher grade of papilloedema and are present in about one third of patients at presentation.[45] Visual field test: diagnosis must include serial perimetry.[1] The visual field defects are the same types that occur in papilloedema due to other causes and are similar to those found in glaucoma. The most common defects are enlargement of the physiological blind spot, loss of inferonasal portions of the visual field, and constriction of isopters.[35] Central defects are uncommon and warrant a search for another diagnosis unless there is a large serous retinal detachment from high-grade optic disc oedema (which can be seen with optical coherence tomography). The loss of visual field may be progressive and severe and lead to blindness. The temporal profile of visual loss is usually gradual. However, acute severe loss of vision of the type found in ischaemic optic neuropathy can occur. In some cases, the vision loss is mild and unlikely to be noticed by the patient.[38]

Intraocular pressure: to exclude hypotony.[46]

Optical coherence tomography: measures the thickness of the retinal nerve fibre layer and quantifies the progress of papilloedema.[44]

Other investigations

All patients should have the following investigations:

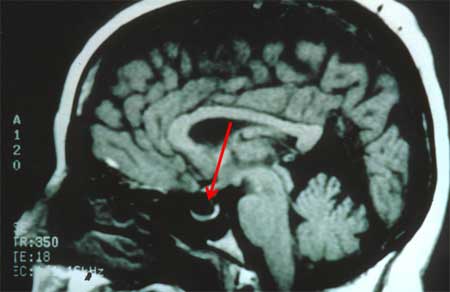

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain with and without contrast: looking for intraorbital and intracranial pathology. Axial and sagittal views are required to assess for empty sella and flattening of the globe.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MRI of empty sella on sagittal viewFrom the personal collection of Dr M. Wall; used with permission [Citation ends].

Lumbar puncture: can be done once intracranial mass lesions have been excluded. Aseptic technique under local anaesthesia is performed using L3/L4 interspace, with the patient in the left lateral decubitus position with legs extended before measuring opening pressure and with normal respiratory rate and depth (no obvious hyper- or hypoventilation). It is often easier to enter the subarachnoid space with the patient in the sitting position and then place the patient in the lateral decubitus position for pressure measurement and CSF collection. Fluoroscopic-guided lumber puncture may be preferred for patients who are very obese. Sedation causes hypoventilation and should not be used when recording intracranial pressure.

Magnetic resonance venogram: for bilateral venous stenosis of the transverse sinus; negative for venous sinus thrombosis.

Laboratory test results are normal except for increased intracranial pressure on CSF manometry. Abnormal neuroimaging results (except for empty sella, unfolded optic nerve sheaths, and partially collapsed lateral sinuses) should lead to a differential diagnosis.

Elevated CSF pressure

There are several issues concerning the measurement of the CSF opening pressure:

The reference level for measurement should be the level of the left atrium, whether the patient is supine, prone, or sitting.

Spuriously high values can occur with the Valsalva manoeuvre and the hypoventilation associated with sedation.[47]

Artifactually low values can occur with hyperventilation in an anxious patient, from reduction in carbon dioxide levels.[48]

Normal limits for CSF opening pressure in people who are obese vary between studies.[49][50][51] There is a slight increase in CSF pressure with an increase in body mass index.[52] Values between 200 mm H2O and 250 mm H2O may be considered borderline, with values >250 mm H2O definitely elevated. In children and adolescents, values >280 mm H2O should be used.[53]

Patients undergoing multiple needle punctures may have falsely low results.

A single normal CSF measurement does not exclude a diagnosis of IIH as CSF pressure fluctuates throughout the day.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer