Approach

Diagnosis is based on the history and clinical findings. Imaging is not often necessary for diagnosis, but is of value in assessment of disease extension and treatment planning.

History and examination

Patients typically present with hearing loss or tinnitus. A history of, or presentation with, recurrent or chronic purulent aural discharge, which may be unresponsive to antibiotic therapy, is common in acquired cholesteatoma. Discharge is malodorous and may be scant. Less commonly, patients present with symptoms of otalgia, vertigo, or facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) involvement (altered taste or facial weakness). These symptoms often signify more advanced disease.[1]

Patients should be questioned about any pre-existing ear disease or causes of eustachian tube dysfunction.[3][16] A co-existing diagnosis of a cleft palate, craniofacial abnormality, or a chromosomal disorder increases the risk of acquired cholesteatoma.[4][8] Less commonly, family members may also have had middle ear disease or cholesteatoma.[13][16][21]

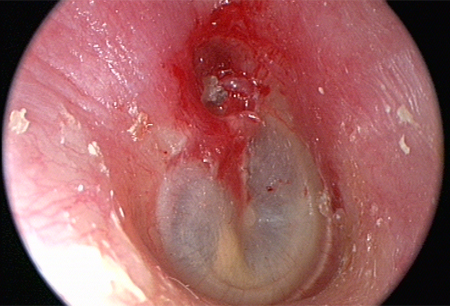

On examination there may be evidence of an ear discharge. Otoscopy typically shows crust or keratin in the attic (upper part of the middle ear), the pars flaccida, or the pars tensa (usually posterior superior aspect), with or without a perforation of the tympanic membrane.[22] A white mass behind an intact tympanic membrane may be observed in congenital cholesteatoma.

How to perform an examination of the ear.

If there is significant aural discharge, the patient may require examination with an otomicroscope and micro-suctioning of the ear. A zero- or thirty-degree endoscope may also be useful in examination of the ear. This can help to differentiate a retraction pocket from cholesteatoma.[23] In patients who are difficult to examine (e.g., small children, those with learning difficulties), it may be necessary to examine the ears under a general anaesthetic. This allows complete micro-suctioning of the ear, determination of the cause of the discharge (whether or not a perforation or retraction pocket is present), and confirmation of the presence of a cholesteatoma.

A fistula test is sometimes performed, using tympanometry to apply positive pressure and recording eye movements. A positive result is nystagmus following positive pressure, signifying the presence of a semicircular canal fistula. However, the test may give a false-negative result.[24][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Retraction pocket in attic (upper part of the middle ear)From Dr Susan Douglas' personal teaching collection [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cholesteatoma in attic (upper part of the middle ear)From Dr Susan Douglas' personal teaching collection [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cholesteatoma in attic (upper part of the middle ear)From Dr Susan Douglas' personal teaching collection [Citation ends].

Audiology

Audiometry should be performed in all patients to determine the patient's hearing status. A hearing test may be normal but more commonly demonstrates a conductive hearing loss.[1] There may be a mixed conductive and sensorineural hearing loss in patients with cochlear damage or in those with a pre-existing hearing loss (e.g., congenital or presbycusis).

Imaging

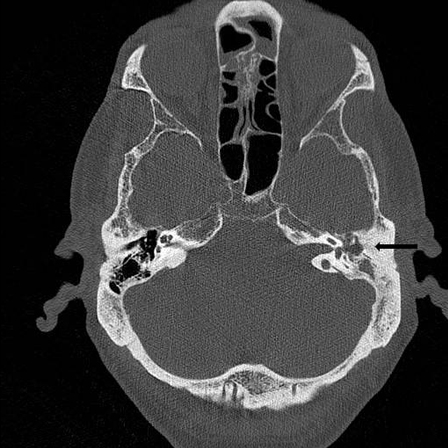

High-resolution CT scan of the petrous temporal bones is recommended as part of the initial work-up of patients with middle ear cholesteatoma.[25][26] It can provide confirmation of disease in patients with an atypical presentation, and can be used to assess the ear for mastoid pathology and complications such as cochlear, semicircular canal, or intracranial involvement.[27] In patients with cholesteatoma, CT shows opacification of the middle ear or mastoid; with or without erosion of the scutum, ossicular chain, labyrinth, facial canal, tegmen, or bony capsule of the sigmoid sinus. CT of the temporal bones without intravenous contrast medium is usually sufficient in the investigation of suspected cholesteatoma and in surgical planning. However, administration of intravenous contrast medium is helpful in demonstrating extra-osseous soft-tissue extension, if there is clinical concern.[26]

MRI is used to characterise soft-tissue pathology in cholesteatoma, complementing CT imaging, which better defines bony involvement. MRI of the head with thin sections across the petrous temporal bone (to image the internal auditory canal), with and without intravenous contrast, is useful in defining the extent of a middle ear cholesteatoma; and in assessing for intracranial extension, prior to surgical intervention.[26]

MRI is the preferred imaging modality for certain intracranial complications of cholesteatoma, including meningoencephalitis; temporal lobe abscess formation; and venous sinus thrombosis.[4]

A non-echo-planar based diffusion-weighted MRI is useful in patients who have already had surgery in order to rule out recurrence of disease.[28][29][30][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cholesteatoma, coronal CT scanFrom Dr Susan Douglas' personal teaching collection [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cholesteatoma, axial CT scanFrom Dr Susan Douglas' personal teaching collection [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cholesteatoma, axial CT scanFrom Dr Susan Douglas' personal teaching collection [Citation ends].

Microbiology

Ear cultures are obtained mainly in patients who present with an aural discharge unresponsive to antimicrobial therapies. Swabs from the ear demonstrate bacterial infection, commonly Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and may demonstrate other pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and anaerobic bacteria.[31]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer