Approach

Oesophageal cancer typically presents late, which in part contributes to the generally poor prognosis. Clinicians need to remain vigilant and investigate patients thoroughly in order to make the diagnosis at the earliest possible opportunity.

Clinical features

The most common presenting signs of oesophageal cancer are dysphagia and odynophagia. For patients with Barrett's oesophagus and early-stage adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and oesophago-gastric junction, reflux is the most common presenting sign. Severe weight loss usually occurs after swallowing difficulties begin.[87]

Phrenic nerve involvement can trigger hiccups. A postprandial or paroxysmal cough may indicate the presence of an oesophago-tracheal or oesophago-bronchial fistula resulting from local invasion by a tumour.

Initial investigations

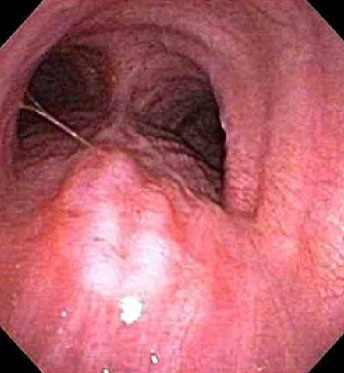

While a patient noting dysphagia is often evaluated first by videoesophagram, if oesophageal cancer is suspected an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is warranted.[88][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic view of oesophageal cancerPersonal collection of Mark J. Krasna [Citation ends]. This allows assessment of any obstruction, and biopsy to confirm the histology of mucosal lesions. The minimal recommended number of biopsies is not defined, but accepted convention is to obtain ≥6 representative biopsies of the lesion.[88] The histological tumour type should be reported according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria.[1] The differentiation between oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OAC) is of clinical and prognostic relevance. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining is recommended in poorly differentiated and undifferentiated cancers when differentiation between OSCC and OAC using morphological features is not possible.[88] Less common tumour types, such as neuroendocrine tumours, lymphomas, mesenchymal tumours, melanomas, and secondary tumours must be identified separately from OSCC and OAC.[88]

This allows assessment of any obstruction, and biopsy to confirm the histology of mucosal lesions. The minimal recommended number of biopsies is not defined, but accepted convention is to obtain ≥6 representative biopsies of the lesion.[88] The histological tumour type should be reported according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria.[1] The differentiation between oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OAC) is of clinical and prognostic relevance. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining is recommended in poorly differentiated and undifferentiated cancers when differentiation between OSCC and OAC using morphological features is not possible.[88] Less common tumour types, such as neuroendocrine tumours, lymphomas, mesenchymal tumours, melanomas, and secondary tumours must be identified separately from OSCC and OAC.[88]

Endoscopy can identify benign causes of obstructive symptoms as well as allow an opportunity for dilation and immediate relief of symptoms.

Laboratory investigations

Serum electrolytes and renal function testing should be performed in advanced cases with near or complete oesophageal obstruction. These patients may become severely volume-depleted and hypokalaemic because of their inability to swallow fluids and their own potassium-rich saliva.

Staging and prognostication

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen is often performed if the suspicion of oesophageal cancer is high or biopsy confirms the diagnosis.[89] Obtaining a (18F)-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan, and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) forms the basis of accurate clinical staging.

EUS allows assessment of the depth of tumour infiltration into or through the oesophageal wall (T stage) and evaluates any concerning locoregional nodal disease. Metastastic disease, when present, is often in the lungs, liver, peritoneum, and/or bones and is best visualised on PET/CT. Lymph node spread is typically to the regional mediastinal lymph nodes, coeliac lymph nodes, para-aortic nodes, and cervical chain. In some countries, abdominal ultrasound is used instead of CT to diagnose metastasis to the liver or coeliac lymph glands.

T1 and T2 lesions generally show an oesophageal mass thickness between 5 mm and 15 mm, and T3 lesions show a thickness >15 mm. T4 lesions show invasion of contiguous structures on CT or EUS. This is occasionally suspected by the presence of 'contact' between the oesophagus and surrounding structures, such as the airway or the great vessels. In general, contact with the aorta of more than 90 degrees circumference is considered suspicious for T4 disease and invasion.[90]

Computed tomography (CT)

The CT scan plays a key role in assessing tumour bulk and in monitoring tumour response to therapy. CT can define whether the tumour has spread from the oesophagus to regional lymph nodes and/or contiguous structures, and indicate the presence of distant metastases.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing T3 tumour at level of inferior pulmonary veinPersonal collection of Mark J. Krasna [Citation ends].

Oral and intravenous contrast should be used to ensure optimal opacification of the lumen and visualisation of the heart, mediastinal vessels, and liver.[89] An oesophageal wall thickness >5 mm is abnormal, regardless of the degree of distension.

CT scans cannot accurately differentiate T1a (no submucosa involvement) disease and T1b (submucosa involvement) disease.[91]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI is an alternative to CT for the staging of oesophageal cancer, particularly in detecting metastatic disease to visceral organs. It is highly accurate when assessing the liver or adrenals and for determining advanced local spread (T4). However, it is less reliable in defining early infiltration (T1 to T3).

MRI appears to be sensitive in predicting mediastinal invasion; the loss of signal in the vessels and the air-filled trachea and bronchi may provide a clear delineation between the tumour and the aorta and the tracheobronchial tree. Like CT scans, MRI scans are poor at detecting tumours restricted to mucosa or submucosa, and also tend to under-stage the regional lymph nodes.[92]

(18F)-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET)

Use of FDG-PET improves the accuracy of staging and facilitates selection of patients for surgery, by detecting distant metastatic disease not identified by CT alone.[89] Positron emission tomography (PET) has a higher sensitivity than CT for detecting nodal and distant metastases, and a higher accuracy for determining resectability than CT. However, there is a high rate of false-positive FDG-PET findings, and small locoregional nodal metastases (<8 mm) cannot be identified reliably by current PET technology.[15][93]

PET can be used to detect responses to chemotherapy and radiotherapy.[94][95][96] In patients with oesophageal cancer, relative changes in FDG uptake can predict response to neoadjuvant therapy.[97][98][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: PET scan showing oesophageal cancer at the gastro-oesophageal junction. Note metastatic deposit in left femurPersonal collection of Mark J. Krasna [Citation ends].

An FDG-PET scan is generally done before EUS to avoid unnecessary testing in patients with metastatic disease.[99]

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) ± fine needle aspiration (FNA)

EUS combined with FNA (EUS/FNA) is the most accurate imaging modality for locoregional staging of oesophageal cancer prior to therapy. The overall accuracy of EUS/FNA in this setting is 87%; the comparable figure for EUS alone is 74%.[100][101]

The accuracy of EUS in staging advanced oesophageal cancer appears to be greater compared with early cancer (sensitivity and specificity of EUS for staging oesophageal cancer: 81.6% and 99.4% in T1 tumours; 81.4% and 96.3% in T2 tumours; 91.4% and 94.4% in T3 tumours; and 92.4% and 97.4% in T4 tumours, respectively).[102] Evidence of lymph node involvement that is proven pathologically by EUS/FNA is considered definitive, and the patient can be referred for the appropriate stage-specific therapy.

EUS re-staging subsequent to neoadjuvant therapy lacks accuracy.[103][104] This is believed to be a function of distortion of the architecture of the oesophageal wall arising from treatment-induced fibrosis and ulceration.

Residual nodal disease following neoadjuvant therapy is an ominous finding. EUS/FNA may have a role, but this may necessitate sampling all visible nodes regardless of criteria for suspiciousness.[105][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of lymph nodePersonal collection of Mark J. Krasna [Citation ends].

EUS findings that indicate a tumour that cannot be resected include invasion into the left atrium, wall of the descending aorta, spinal body, pulmonary vein or artery, or tracheobronchial system. The latter should be confirmed by bronchoscopy with transbronchial FNA. Stenosis can limit the clinical utility of EUS.[106]

Complications of EUS (with or without FNA) include perforation (0.02% to 0.08%), haemorrhage (0.13% to 0.69%), and infection (0.4% to 1.7%).[107]

Bronchoscopy

In patients with disease of the middle and upper thirds of the oesophagus, bronchoscopy with biopsy, FNA, or brushings can be helpful in determining involvement of the tracheobronchial tree. Bronchoscopy should be performed prior to considering surgery on tumours at these locations.

FNA can be performed into mucosal lesions within the lumen, or transbronchially into lesions adjacent to the airway.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Tracheal invasion (T4) confirmed by bronchoscopyPersonal collection of Mark J. Krasna [Citation ends].

Thoracoscopy/laparoscopy

Thoracoscopic or laparoscopic staging is rarely needed but may be appropriate in selected patients; for example, those with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus or oesophagogastric junction with significant extension into the cardia.[108] European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines recommend laparoscopy in patients with locally advanced (T3/4) adenocarcinomas of the oesophago-gastric junction to rule out peritoneal metastases (which are found in approximately 15% of patients). Tumours extending more than 4 cm beyond the gastro-oesophageal junction are at particular risk for peritoneal disease. The finding of otherwise unknown metastases may spare patients from undergoing futile surgery.[88] Studies indicate that thoracoscopy and laparoscopy may improve accuracy compared with non-invasive testing in these situations.[109][110]

Clinical examination of the head and neck region

A qualified clinical examination of the head and neck region is recommended in patients with OSCC to exclude concurrent head and neck second primary tumours (HNSPTs). The pooled prevalence of HNSPTs in patients with OSCC is 6.7%, and prognosis of patients with an additional HNSPT is worse than for patients with only OSCC. Early detection of HNSPTs may improve the outcome for patients with OSCC.[88]

Molecular and pathological tests

Should be carried out at diagnosis to determine suitability for targeted therapies or immunotherapy.

All newly diagnosed patients should be tested for microsatellite instability (MSI) or mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR). Programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) testing is recommended in those with advanced or metastatic oesophageal cancers.

Testing for MSI and dMMR is performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue. MSI status is assessed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or next-generation sequencing (NGS) to measure gene expression levels of microsatellite markers (BAT25, BAT26, MONO27, NR21, NR24). MMR deficiency is evaluated by immunohistochemistry (IHC) to assess nuclear expression of proteins involved in DNA mismatch repair (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2).[15] Results are interpreted as MSI-high (MSI-H) or MMR-deficient (dMMR) as per the College of American Pathologists (CAP) DNA mismatch repair biomarker reporting guidelines.[111]

A qualitative IHC assay is used to detect PD-L1 protein levels in FFPE tumour tissue. The combined positive score (CPS) is used to evaluate if a specimen is considered to have PD-L1 expression. The CPS is determined by the number of PD-L1 stained cells (i.e., tumour cells, lymphocytes, macrophages) divided by the total number of viable tumour cells evaluated, multiplied by 100. A CPS ≥1 indicates that a specimen has PD-L1 expression.[15][112] An alternative is the tumour proportion score (TPS): this evaluates the percentage of viable tumour cells showing partial or complete membrane staining at any intensity (PD-L1 positivity is defined as TPS ≥1%).[88] TPS is only used in clinical-decision making for metastatic squamous cell carcinoma (based on CheckMate 648), whereas CPS is used in oesophageal and junctional adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.[113]

All patients with inoperable locally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic EAC should should have human epidermal receptor 2 (HER2) status determined on diagnosis, as HER2-positive patients benefit from the addition of trastuzumab to first-line palliative chemotherapy.[15][114] HER2-targeting is not routine practice in earlier disease settings, and consequently, establishing HER2 status would not impact clinical management outside the context of clinical trials. The reported rates of HER2 positivity in oesophageal cancers vary widely (2% to 45%) and are more frequently seen in adenocarcinoma (15% to 30%) than in squamous cell carcinoma (5% to 13%).[15]

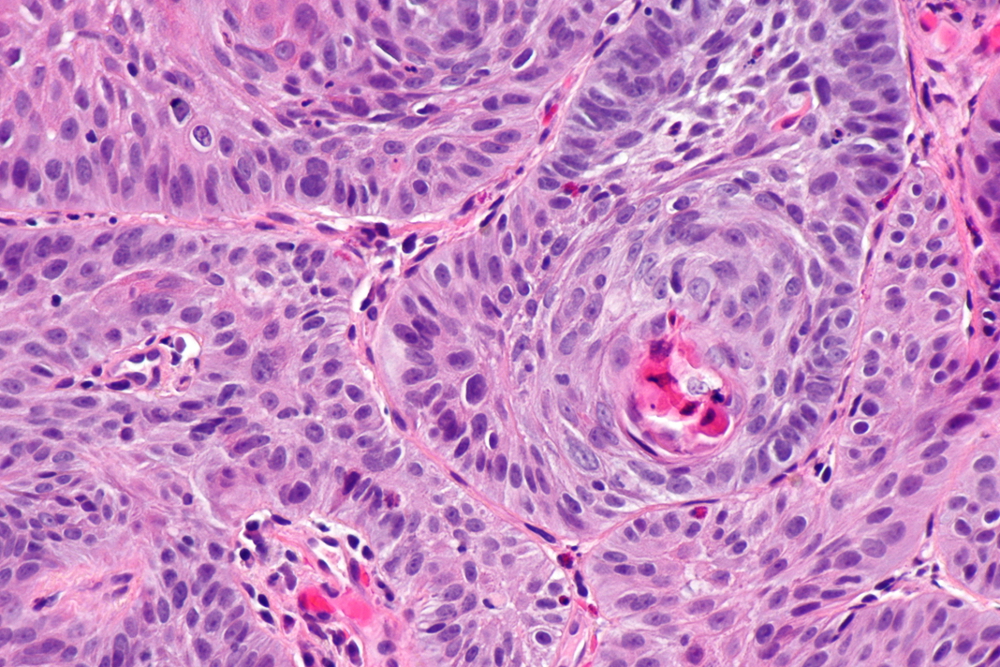

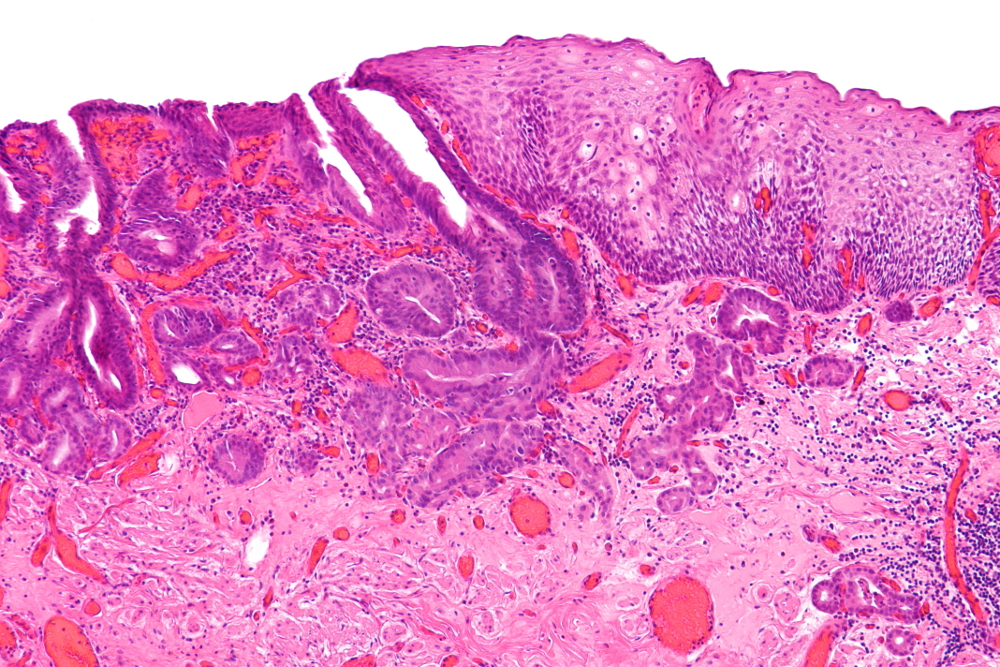

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Moderated differentiated, keratinising oesophageal carcinomaWikimedia: Nephron https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Adenocarcinoma (left of image) demonstrating glandular appearance with numerous mitotic cells and variable nuclear size and shape. Normal squamous epithelium is visible on the right of the imageWikimedia: Nephron https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Adenocarcinoma (left of image) demonstrating glandular appearance with numerous mitotic cells and variable nuclear size and shape. Normal squamous epithelium is visible on the right of the imageWikimedia: Nephron https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en [Citation ends].

Liquid biopsy

Liquid biopsy involves evaluating circulating tumour DNA by means of a blood test. It is used to detect mutations in DNA shed from oesophageal cancer, which can help to identify alterations that are targetable by available treatments. It is being used more frequently in patients with advanced or metastatic disease, especially those who are unable to undergo clinical biopsy for disease surveillance and management. A negative result does not exclude the presence of tumour mutations or amplifications and should therefore be interpreted with caution.[15]

Preoperative assessment

Management of locoregional oesophageal carcinoma often requires intensive therapy with a combination typically of induction chemoradiation (or chemotherapy alone) followed by surgery. However, many patients present with advanced disease and comorbidities that may affect the suitability of this treatment pathway.

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) are crucial to determine the ability of the patient to withstand combined modality therapy. In patients with poor PFT results, a less invasive surgical approach, such as abdominocervical (transhiatal) oesophagectomy without thoracotomy, may be associated with lower morbidity and mortality.

Cardiac risk is assessed with cardiac stress testing and echocardiogram.

Nutritional status and history of weight loss should be assessed and nutritional support offered to all patients, in both curative and palliative settings. More than 50% of patients lose >5% of their body weight before admission for oesophagectomy, and 40% of patients lose >10%. Weight loss (independent of body mass index) is associated with increased operative risk, reduced quality of life, and poor survival in advanced disease.[88] The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommends using European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) guidelines to aid assessment and management.[88][115] Correction of malnutrition may be needed before curative-intent therapy can be started. While swallowing function generally improves after induction therapy, concerning levels of weight loss and malnutrition on presentation should be addressed early with enteral feeding, typically with placement of a gastrostomy or feeding jejunostomy tube.[88]

Exercise status should be asked about; reduced physical activity is associated with worse outcomes following perioperative treatment, and lower physical fitness is a negative predictor of long-term survival in oesophageal cancer. A supervised exercise programme has been shown to improve cardiorespiratory fitness and some aspects of quality of life in patients who have undergone oesophagectomy and is recommended in European guidelines.[88]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer