Small asymptomatic pterygia requires no treatment. Patients should be advised to protect their eyes from ultraviolet light with good-quality wraparound sunglasses and hats with peaked brims.

Symptomatic management

If the patient has symptoms of ocular irritation, burning, or itching, these may be alleviated with topical artificial tear preparations. If these symptoms are associated with inflammation of the pterygium, topical corticosteroids such as fluorometholone or loteprednol may be prescribed under ophthalmologic supervision with regular monitoring of intraocular pressure, initially at 2-3 weeks, because of the risk of topical corticosteroid-induced ocular hypertension/glaucoma.[15]The College of Optometrists. Pterygium. Jun 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/clinical-management-guidelines/pterygium

The indications for surgical intervention include:

Significant ocular irritation unresolved by medical therapy

Impaired ocular cosmesis

Reduced visual acuity from induced astigmatism or encroachment of the pterygium to or over the visual axis

Continued documented progression, so that it can be assumed that eventual visual impairment is likely

Double vision secondary to restriction or tethering of the medial rectus muscle.

Before surgery it must be ensured that the lesion is a true pterygium and not one of the mimicking conditions such as a pseudopterygium. The patient requires careful preoperative counseling that, while pterygium surgery is generally successful, symptoms of ocular irritation and burning may not be entirely relieved, and persistent redness and deep corneal scarring beneath the pterygium may mean that improvement in ocular cosmesis is only partial. Furthermore, the patient needs to be advised that recurrences after surgical removal are not infrequent and may be aggressive. For these reasons, surgery is not generally recommended for small pterygia or for cosmetic reasons alone.

There are a variety of surgical approaches, underscoring the point that no method is entirely successful.

Surgical techniques

Simple excision

Often this can be performed simply by mechanically shearing off the head and body of the pterygium from the underlying cornea using forceps and then excising it, leaving bare sclera underneath. If it is adherent, careful superficial dissection can be performed. While this is simple and quick to perform, high recurrence rates (>33%) have been reported after simple excision.[19]Youngson RM. Recurrence of pterygium after excision. Br J Ophthalmol. 1972 Feb;56(2):120-5.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1208696

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5010313?tool=bestpractice.com

Redirection of the head of the pterygium

These techniques, which entailed redirecting the pterygium head by burying it beneath the conjunctival edge following dissection of the pterygium from the cornea, have been abandoned due to high recurrence rates.

Conjunctival autografting and flaps

This is the most commonly used surgical technique and involves covering the bare scleral area created following pterygium removal and excision with either rotational conjunctival flaps above and/or below or with a free conjunctival graft taken from the superior bulbar conjunctiva. As well as covering the bare scleral area, it is thought that the graft acts as a barrier to recurrence. Published recurrence rates after conjunctival autografting techniques are encouraging (between 5% and 15%), with studies suggesting even lower rates with the inclusion of limbal tissue within the graft.[19]Youngson RM. Recurrence of pterygium after excision. Br J Ophthalmol. 1972 Feb;56(2):120-5.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1208696

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5010313?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Allan BD, Short P, Crawford GJ, et al. Pterygium excision with conjunctival autografting: an effective and safe technique. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:698-701.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC504627

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8280682?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]Al Fayez MF. Limbal versus conjunctival autograft transplantation for advanced and recurrent pterygium. Ophthalmology. 2002 Sep;109(9):1752-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12208727?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]Zheng K, Cai J, Jhanji V, et al. Comparison of pterygium recurrence rates after limbal conjunctival autograft transplantation and other techniques: meta-analysis. Cornea. 2012 Dec;31(12):1422-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22643650?tool=bestpractice.com

The use of fibrin sealant instead of sutures has been shown not only to reduce operative time but also to improve postoperative patient comfort.[23]Ozdamar Y, Mutevelli S, Han U, et al. A comparative study of tissue glue and vicryl suture for closing limbal-conjunctival autografts and histologic evaluation after pterygium excision. Cornea. 2008 Jun;27(5):552-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18520504?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Ratnalingam V, Eu AL, Ng GL, et al. Fibrin adhesive is better than sutures in pterygium surgery. Cornea. 2010 May;29(5):485-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20308876?tool=bestpractice.com

Results from meta-analyses suggest that it might reduce recurrence rates.[25]Shi YJ, Yan ZG, Yue HY, et al. Meta-analysis of fibrin glue for attaching conjunctival autografts in pterygium surgery. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2011 Jun;47(6):550-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21914272?tool=bestpractice.com

[26]Pan HW, Zhong JX, Jing CX. Comparison of fibrin glue versus suture for conjunctival autografting in pterygium surgery: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2011 Jun;118(6):1049-54.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21292327?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

What are the benefits and harms of conjunctival autograft in people with pterygium?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.1408/fullShow me the answer

[

]

What are the benefits and harms of conjunctival autograft in people with pterygium?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.1408/fullShow me the answer

[  ]

How does fibrin glue compare with sutures for conjunctival autografting in primary pterygium surgery?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.1564/fullShow me the answer

]

How does fibrin glue compare with sutures for conjunctival autografting in primary pterygium surgery?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.1564/fullShow me the answer

Amniotic membrane transplantation

Instead of conjunctiva, amniotic membrane may be used to cover the bare scleral area, with some studies demonstrating recurrence rates comparable with those of conjunctival autografting, and others increased.[19]Youngson RM. Recurrence of pterygium after excision. Br J Ophthalmol. 1972 Feb;56(2):120-5.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1208696

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5010313?tool=bestpractice.com

[27]Ma DH, See LC, Liau SB, et al. Amniotic membrane graft for primary pterygium: comparison with conjunctival autograft and topical mitomycin C treatment. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000 Sep;84(9):973-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10966947?tool=bestpractice.com

[28]Luanratanakorn P, Ratanapakorn T, Suwan-Apichon O, et al. Randomised controlled study of conjunctival autograft versus amniotic membrane graft in pterygium excision. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006 Dec;90(12):1476-80.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1857513

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16837545?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Li M, Zhu M, Yu Y, et al. Comparison of conjunctival autograft transplantation and amniotic membrane transplantation for pterygium: a meta-analysis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012 Mar;250(3):375-81.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21935607?tool=bestpractice.com

However, in cases where the pterygium is very extensive, necessitating a large area of coverage, and in glaucoma patients, where it is desirable to preserve the superior bulbar conjunctiva for future drainage surgery, amniotic membrane transplantation can be very useful.[27]Ma DH, See LC, Liau SB, et al. Amniotic membrane graft for primary pterygium: comparison with conjunctival autograft and topical mitomycin C treatment. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000 Sep;84(9):973-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10966947?tool=bestpractice.com

[30]Ozer A, Yildirim N, Erol N, et al. Long-term results of bare sclera, limbal-conjunctival autograft and amniotic membrane graft techniques in primary pterygium excisions. Ophthalmologica. 2009;223(4):269-73.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19339811?tool=bestpractice.com

Lamellar keratoplasty

Partial thickness corneal transplantation may be required if corneal thinning is significant. This is unusual and typically occurs in cases of recurrent pterygia following previous attempts at surgical removal. In very aggressive cases involving the visual axis, residual scarring and stromal irregularity may necessitate lamellar or even penetrating keratoplasty for visual rehabilitation.

Excimer laser phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK)

Typically such procedures are performed under local anesthesia. Subconjunctival injection of lidocaine is effective, as is topical application of ophthalmic lidocaine gel.[31]Page MA, Fraunfelder FW. Safety, efficacy, and patient acceptability of lidocaine hydrochloride ophthalmic gel as a topical ocular anesthetic for use in ophthalmic procedures. Clin Ophthalmol. 2009;3:601-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2773282

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19898665?tool=bestpractice.com

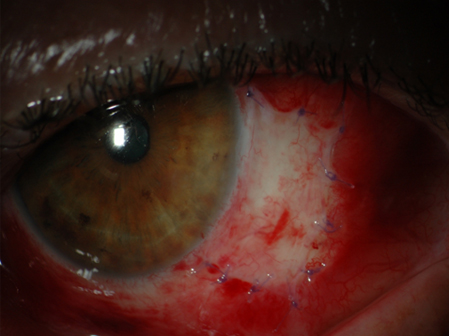

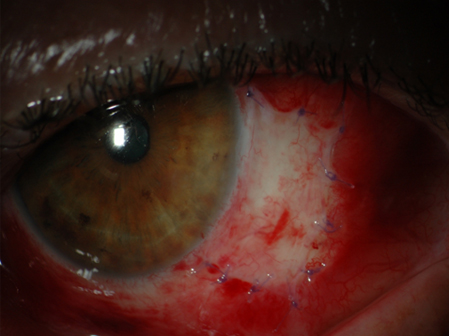

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Eye following pterygium excision and conjunctival autografting 1 day after surgeryFrom personal collection of David O'Brart; used with permission [Citation ends].

Adjunctive medications and therapy

Various agents have been used in an effort to reduce recurrence after primary surgery and especially to treat recurrent disease. Such agents include postoperative regimens of thiotepa and mitomycin eye drops, perioperative mitomycin and daunorubicin application, fluorouracil, and beta-radiation therapy using strontium-90 plaques.[32]Asregadoo ER. Surgery, thio-tepa, and corticosteroid in the treatment of pterygium. Am J Ophthalmol. 1972 Nov;74(5):960-3.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4630176?tool=bestpractice.com

[33]Singh G, Wilson MR, Foster CS. Long-term follow-up study of mitomycin eye drops as adjunctive treatment of pterygia and its comparison with conjunctival autograft transplantation. Cornea. 1990 Oct;9(4):331-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2078962?tool=bestpractice.com

[34]Frucht-Pery J, Siganos CS, Ilsar M. Intraoperative application of topical mitomycin C for pterygium surgery. Ophthalmology. 1996 Apr;103(4):674-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8618770?tool=bestpractice.com

[35]Dadeya S, Kamlesh. Intraoperative daunorubicin to prevent the recurrence of pterygium after excision. Cornea. 2001 Mar;20(2):172-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11248823?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Bahrassa F, Datta R. Postoperative beta radiation treatment of pterygium. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1983 May;9(5):679-84.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6853267?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Kal HB, Veen RE, Jürgenliemk-Schulz IM. Dose-effect relationships for recurrence of keloid and pterygium after surgery and radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009 May 1;74(1):245-51.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19362243?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Bekibele CO, Ashaye A, Olusanya B, et al. 5-Fluorouracil versus mitomycin C as adjuncts to conjunctival autograft in preventing pterygium recurrence. Int Ophthalmol. 2012;32:3-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2246200?tool=bestpractice.com

[39]Lee BWH, Sidhu AS, Francis IC, et al. 5-Fluorouracil in primary, impending recurrent and recurrent pterygium: systematic review of the efficacy and safety of a surgical adjuvant and intralesional antimetabolite. Ocul Surf. 2022 Oct;26:128-41.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35961535?tool=bestpractice.com

While such adjunctive agents may reduce rates of recurrence following simple excision, their use can be associated with significant sight-threatening complications such as corneal endothelial cell loss, scleral ulceration, melting, and even perforation.[39]Lee BWH, Sidhu AS, Francis IC, et al. 5-Fluorouracil in primary, impending recurrent and recurrent pterygium: systematic review of the efficacy and safety of a surgical adjuvant and intralesional antimetabolite. Ocul Surf. 2022 Oct;26:128-41.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35961535?tool=bestpractice.com

[40]Rubinfeld RS, Pfister RR, Stein RM, et al. Serious complications of topical mitomycin-C after pterygium surgery. Ophthalmology. 1992 Nov;99(11):1647-54.

https://www.aaojournal.org/article/S0161-6420(92)31749-X/pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1454338?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Moriarty AP, Crawford GJ, McAllister IL, et al. Severe corneoscleral infection. A complication of beta irradiation scleral necrosis following pterygium excision. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993 Jul;111(7):947-51.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8328937?tool=bestpractice.com

[42]Kheirkhah A, Izadi A, Kiarudi MY, et al. Effects of mitomycin C on corneal endothelial cell counts in pterygium surgery: role of application location. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011 Mar;151(3):488-93.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21236405?tool=bestpractice.com

In view of such potential complications and the limited follow-up studies available for cases where adjunctive medications have been used, conjunctival autografting is the most popular surgical technique.[30]Ozer A, Yildirim N, Erol N, et al. Long-term results of bare sclera, limbal-conjunctival autograft and amniotic membrane graft techniques in primary pterygium excisions. Ophthalmologica. 2009;223(4):269-73.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19339811?tool=bestpractice.com

In a 10-year follow-up study of a randomized controlled trial, limbal conjunctival autografting reduced pterygium recurrence compared with mitomycin, although no long-term complications or endothelial cell loss were seen in the mitomycin group.[43]Young AL, Ho M, Jhanji V, et al. Ten-year results of a randomized controlled trial comparing 0.02% mitomycin C and limbal conjunctival autograft in pterygium surgery. Ophthalmology. 2013 Dec;120(12):2390-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23870302?tool=bestpractice.com

More recently the use of topical monoclonal antibodies against vascular endothelial growth factors (anti-VEGF) has been advocated as an adjunctive therapy postoperatively, either in drop form or as subconjunctival injections.[44]Fallah MR, Khosravi K, Hashemian MN, et al. Efficacy of topical bevacizumab for inhibiting growth of impending recurrent pterygium. Curr Eye Res. 2010;35:17-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20021250?tool=bestpractice.com

In a meta-analysis, topical/subconjunctival bevacizumab was relatively safe, associated only with an increased risk of subconjunctival hemorrhage, but it had no significant effect on preventing pterygium recurrence.[45]Hu Q, Qiao Y, Nie X, et al. Bevacizumab in the treatment of pterygium: a meta-analysis. Cornea. 2014 Feb;33(2):154-60.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24326333?tool=bestpractice.com

In another meta-analysis, conjunctival autograft combined with cyclosporine eye drops was the best adjunctive treatment to prevent recurrence following primary pterygium surgery.[46]Fonseca EC, Rocha EM, Arruda GV. Comparison among adjuvant treatments for primary pterygium: a network meta-analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018 Jun;102(6):748-56.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29146761?tool=bestpractice.com

The role of such agents as a primary therapy without adjunctive surgery is equivocal.[45]Hu Q, Qiao Y, Nie X, et al. Bevacizumab in the treatment of pterygium: a meta-analysis. Cornea. 2014 Feb;33(2):154-60.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24326333?tool=bestpractice.com

[47]Mandalos A, Tsakpinis D, Karayannopoulou G, et al. The effect of subconjunctival ranibizumab on primary pterygium: a pilot study. Cornea. 2010 Dec;29(12):1373-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20856107?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]Fallah Tafti MR, Khosravifard K, Mohammadpour M, et al. Efficacy of intralesional bevacizumab injection in decreasing pterygium size. Cornea. 2011 Feb;30(2):127-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20885313?tool=bestpractice.com

Recurrent pterygia

Treatment of recurrent pterygia can be problematic. Dissection of recurrent lesions from the cornea can be difficult. Such lesions do not usually shear off the surface mechanically but adhere firmly to the underlying corneal stroma and require sharp dissection. Underlying thinning of the cornea may be present and, occasionally, lamellar corneal transplantation may be required to restore the normal surface contour.

Recurrent pterygia have a higher rate of recurrence after excision than primary lesions. Many surgeons advocate using adjunctive therapies such as topical mitomycin when treating such lesions, although their use can be associated with significant sight-threatening complications such as scleral melting.[40]Rubinfeld RS, Pfister RR, Stein RM, et al. Serious complications of topical mitomycin-C after pterygium surgery. Ophthalmology. 1992 Nov;99(11):1647-54.

https://www.aaojournal.org/article/S0161-6420(92)31749-X/pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1454338?tool=bestpractice.com

It is the author's preference not to use such agents, but to perform a repeat conjunctival autografting technique with the inclusion of limbal tissue within the graft.[21]Al Fayez MF. Limbal versus conjunctival autograft transplantation for advanced and recurrent pterygium. Ophthalmology. 2002 Sep;109(9):1752-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12208727?tool=bestpractice.com

Histology

It is highly recommended that all excised pterygia undergo formal histologic examination. Typical histologic features of pterygia include limbal epithelial cell proliferation, goblet cell hyperplasia, angiogenesis, inflammation, Bowman layer disruption, elastosis and stromal plaques. Pre-neoplastic lesions have been identified in pterygia, as well as reports of unsuspected and potentially malignant ocular surface disorders.[49]Oellers P, Karp CL, Sheth A, et al. Prevalence, treatment, and outcomes of coexistent ocular surface squamous neoplasia and pterygium. Ophthalmology. 2013 Mar;120(3):445-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3562397

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23107578?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]Chui J, Coroneo MT, Tat LT, et al. Ophthalmic pterygium: a stem cell disorder with premalignant features. Am J Pathol. 2011 Feb;178(2):817-27.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3069871

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21281814?tool=bestpractice.com

]

[

]

[  ]

]