Approach

Clinical suspicion and diagnosis of Vibrio syndromes depend on a history of handling or cleaning shellfish, ingestion of shellfish, or exposure to brackish/ocean waters, particularly when coupled with a host with underlying comorbidity (e.g., immunocompromised, with underlying liver disease).

Vibrio infections can present as:

Sepsis or severe systemic infection associated with ingestion of shellfish with or without metastatic necrotizing cellulitis or peripheral symmetrical gangrene

Local inoculation wound with localized skin/soft-tissue infection with or without sepsis or severe systemic infection

Gastroenteritis syndromes

Superficial inoculation infections (i.e., conjunctivitis, external otitis).

Sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. Septic shock is defined as a subset of sepsis with circulatory and cellular or metabolic dysfunction associated with a higher risk of mortality.[35]

Sepsis or severe systemic infection associated with ingestion of shellfish

Vibrio vulnificus or Vibrio parahaemolyticus acquired through ingestion of raw or undercooked shellfish can rapidly produce fatal septic shock in immunocompromised patients or those with underlying liver disease. Within hours to days of ingesting the shellfish, the patient can develop sepsis with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and metastatic necrotizing soft-tissue infection of the lower extremities.

If no skin lesions are present, other causes of sepsis (of which there are many) must be considered. A high level of suspicion should arise if there is a medical history of hepatic disorder or immunodeficiency, and recent shellfish consumption or marine contact.

Clinical findings of sepsis (e.g., fever, tachycardia, tachypnea) may be present, and the patient may appear apprehensive. Severe illness manifests by the presence of laboratory evidence of organ dysfunction, and patient confusion and obtundation may be present. In septic shock, the patient is hypotensive and poorly responsive to fluid challenge.

Tests that should be performed include:

Complete blood count with differential and platelet count: a white blood cell count may show neutropenia, and platelet count may be decreased

Basic metabolic panel: bicarbonate levels may be decreased indicating metabolic acidosis; creatinine may be elevated suggesting renal dysfunction

Diagnosis is confirmed by blood culture: blood cultures should be obtained before starting treatment with antibiotics if doing so results in no substantial delay to treatment (i.e., <45 minutes).[35]

In patients with clinically suspected but unconfirmed sepsis, blood lactate may be used as an adjunctive diagnostic test.[35] Culture independent pathogen diagnosis has been reported using metagenomic next generation gene sequencing.[36]

For further information on the diagnosis of sepsis, please see Sepsis in adults.

Localized skin/soft-tissue infection associated with local inoculation wound

Infection associated with skin inoculation results from brackish or ocean water contaminating an open lesion or as a result of sustaining a penetrating injury. The injury can evolve over hours to days from a local cellulitis into a necrotizing skin and soft-tissue infection, and can be accompanied by bacteremia and sepsis in a susceptible host (e.g., immunocompromised, with underlying liver disease).[21][37]

Diagnosis should be suspected based on the epidemiologic history of shellfish exposure and/or brackish/ocean water exposure of an existing open wound or receipt of a marine-related puncture wound.

Clinical findings vary depending on the level of soft-tissue involvement, the occurrence of bacteremia, and the host's systemic response to infection.

Tests that should be performed include:

Complete blood count with differential and platelet count: white blood cell count may be elevated, normal, or decreased. Platelets may be normal or decreased

Basic metabolic panel: bicarbonate levels may be decreased indicating metabolic acidosis; creatinine may be elevated suggesting renal dysfunction

A blood culture may identify the causative agent: blood cultures should be obtained before starting treatment with antibiotics if doing so results in no substantial delay to treatment (i.e., <45 minutes)[35]

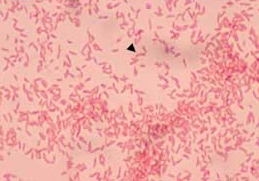

Wound Gram stain and culture: the cutaneous bullae fluid and the ulcer base should be swabbed for Gram stain. A stain demonstrating gram-negative rods in the setting of a patient with underlying comorbidities and shellfish or marine water exposure suggests Vibrio infection.

Culture-independent diagnostic testing: can be used to identify Vibrio, but positive specimen should be confirmed by culture where possible.[38] MALDI-TOF (matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectroscopy) can be used to rapidly identify cultured organisms.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gangrenous change with hemorrhagic bullae in a patient with cirrhosis who developed septic shock and Vibrio vulnificus bacteremiaFrom the image collection of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vibrio vulnificus inoculation injury with early cellulitisFrom the image collection of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vibrio vulnificus inoculation injury with early cellulitisFrom the image collection of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gram-negative curved bacilli (arrowhead) isolated from a blood sampleFrom the image collection of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gram-negative curved bacilli (arrowhead) isolated from a blood sampleFrom the image collection of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Citation ends].

Gastroenteritis syndromes

Ingesting raw or undercooked seafood may result within 24 to 72 hours in a gastroenteritis marked by abdominal cramping and watery diarrhea. There may be accompanying fever and the diarrheal fluid may contain mucus and/or blood. In an otherwise-healthy host, this is usually a self-limiting illness.[39] It may occur as concomitant symptoms with sepsis in a compromised host.[4][21][28]

Diagnostic suspicion should be prompted by the history of recent shellfish consumption. The vibrios grow well but may not be readily identified from the routine culture media used by the clinical laboratory for stool pathogen isolation.

Tests include:

Stool culture: with the suspicion of a Vibrio infection and particularly Vibrio parahaemolyticus, culture of stool on a Vibrio-selective media (i.e., thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose [TCBS] culture medium) should be ordered in the diarrhea workup.[40] The differential diagnosis of food-associated diarrhea includes Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, and norovirus, among other pathogens[41]

Routine blood chemistries: indicated to assess the patient's degree of dehydration and metabolic acidosis from stool electrolyte loss

Blood culture: indicated if the patient is febrile or has other signs of possible sepsis.

Culture-independent diagnostic testing: can be used to identify Vibrio, for example, stool specimen tested with diagnostic polymerase chain reaction array. Positive specimens should be confirmed by culture where possible.[38] MALDI-TOF (matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectroscopy) can be used to rapidly identify cultured organisms.

Superficial inoculation infections

Non-cholera vibrios have been reported to cause ear and eye infections, such as otitis externa, conjunctivitis, keratitis, or endophthalmitis, after injuries with shell fragments, seawater contamination, or penetrating wounds.[42][4]

Signs and symptoms of non-cholera Vibrio ear infection mimic other causes of otitis externa. The diagnosis is suggested by isolation of a Vibrio from external ear canal cultures, and poor or slow clinical improvement with topical antibiotics containing polymyxin, bacitracin, and neomycin. In case of eye infection, the diagnosis is made by Gram-stained smear, culture, and in vitro susceptibility testing of isolates from appropriate ocular specimens (i.e., conjunctival swab, corneal scraping, and anterior or posterior chamber aspirates for conjunctivitis, keratitis, hypopyon, or endophthalmitis, respectively).

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer