Approach

Lung abscess most commonly runs a subacute or chronic course with an insidious onset of nonspecific symptoms and general malaise, but it may present acutely with aggressive infection. The duration of symptoms before diagnosis is extremely variable, ranging from several days to 6 weeks.[14][15][22]

Patients with a suspected lung abscess should be referred to a pulmonologist for further investigation and management.

Clinical history

Presenting symptoms

Lung abscess may present with acute (a few days to <2 weeks), subacute (≥2 weeks), or chronic (>1 month) symptoms.

Acute symptoms include high fever (>101°F [>38.5°C]), a productive cough with purulent sputum, and pleuritic chest pain. Rigors are rare.[2]

Subacute symptoms that last several weeks include profound weight loss, malaise, low-grade fever, night sweats, and a productive cough, mimicking hematological and other malignancy.

Chronic lung abscess may present with hemoptysis. Although usually minor, hemoptysis can be massive.[25]

Large amounts of purulent secretions are usually expectorated in weeks 2-3. Putrid, foul-smelling, sputum is present in about 50% of patients and is highly suggestive of an anaerobic infection.[2]

Lung abscesses secondary to septic embolism from right-sided (e.g., tricuspid valve) bacterial endocarditis or septic thrombophlebitis is associated with bacteremia leading to (high fever, chills, and rigors). Other clinical features of bacterial endocarditis include weakness, arthralgias, and hemorrhagic lesions of the skin and retina. Lung abscesses due to infection after pulmonary infarcts have a preceding history of chest pain, dyspnea, and hemoptysis, followed by a persistent fever.

Historic features that should raise the suspicion of a malignancy causing bronchial obstruction and abscess formation include a low-grade fever, minimal systemic complaints, absence factors predisposing to aspiration, and a deteriorating course.[26]

There may be a preceding episode of lost consciousness due to alcohol abuse, drug overdose, or seizure in aspiration-related lung abscess.

Past medical history and risk factors

Patients should be questioned about the presence of risk factors known to be associated with developing lung abscess.

There may be a history of neurologic disease (e.g., stroke, bulbar dysfunction) or esophageal disease (stricture, malignancy, and reflux) associated with aspiration, or poor dental hygiene, or gingivitis. There may also be a recent history of pneumonia, general anesthesia, nasogastric or endotracheal tube insertion, or oropharyngeal surgery (including tooth extraction or other dental surgery).

Risk factors for pulmonary embolism should be investigated when suspected.

Underlying chronic illnesses predisposing to lung abscess (e.g., COPD, bronchiectasis, diabetes mellitus, scleroderma, esophageal diverticulum, liver and kidney disease) or immunosuppression (e.g., chemotherapy, organ transplantation, corticosteroid therapy, HIV infection) should also be noted.

Physical exam

General exam

Fever may be present (>101°F [>38.5°C]).

Cachexia due to a poor nutritional status and pallor (skin and subconjunctival) due to anemia of chronic disease. Finger clubbing is rarely seen.

Gingival disease with associated halitosis.

An absent gag reflex in patients with an underlying neurologic disorder.

Features of right-sided bacterial endocarditis, such as a new or worsening cardiac murmur and hemorrhagic lesions of the skin and retina.

Respiratory exam

Auscultation over the lung abscess often reveals amphoric or cavernous breath sounds (i.e., like blowing over the mouth of a bottle).

Lung findings consistent with parenchymal consolidation (e.g., inspiratory crackles, bronchial breathing) or empyema (e.g., decreased breath sounds) may be present.

A fixed rhonchus limited to 1 hemithorax indicates a possible airway obstruction due to a tumor or foreign body.

Initial investigations

The initial evaluation of patients with suspected lung abscess should include a complete blood count (CBC) and chest x-ray.

CBC: often reveals pronounced leukocytosis (usually >15,000 WBC/microliter), but it may show anemia of chronic disease.

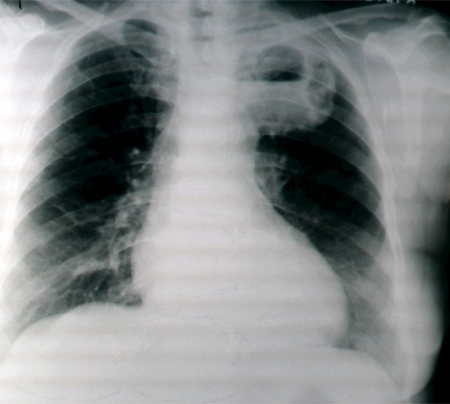

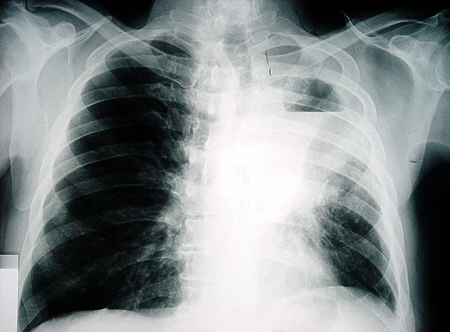

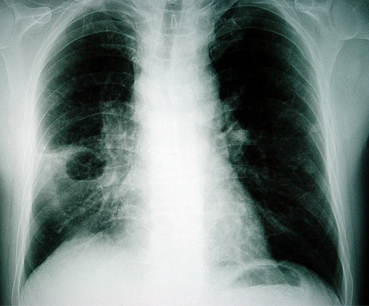

Chest x-ray: may reveal classical segmental or lobar consolidation with central cavitation, an air-fluid level, and thick and irregular cavity walls.

Aspiration-related lung abscesses are usually found in the right lung and dependent lung areas (i.e., posterior segment of the right upper lobe and superior segments of both lower lobes).

Multilobar involvement with multiple peripheral abscesses suggests hematogenous dissemination from extrapulmonary sepsis (e.g., septic embolism).

Chest x-ray in the supine or semi-recumbent position (e.g., in ICU or emergency departments) is often insensitive for diagnosing lung abscess.[9][27]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing a left upper lobe lung abscessFrom the collection of Dr Ioannis P. Kioumis [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing a left-sided lung abscess with surrounding infiltrationFrom the collection of Dr Ioannis P. Kioumis [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing a left-sided lung abscess with surrounding infiltrationFrom the collection of Dr Ioannis P. Kioumis [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing a left-sided cavitating lesion with an air-fluid levelFrom the collection of Dr Ioannis P. Kioumis [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing a left-sided cavitating lesion with an air-fluid levelFrom the collection of Dr Ioannis P. Kioumis [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing a right-sided lung abscess with surrounding infiltrationFrom the collection of Dr Ioannis P. Kioumis [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing a right-sided lung abscess with surrounding infiltrationFrom the collection of Dr Ioannis P. Kioumis [Citation ends].

Bacteriologic exam

Sputum

Expectorated sputum cultures are of limited value because they are usually contaminated by the normal flora of the mouth and respiratory tract. However, despite their low diagnostic yield in lung abscess, expectorated sputum should be stained and cultured in all patients.

Sputum from immunocompromised patients should be specifically stained and cultured for aerobic bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, and parasites.

Gram staining is a simple and useful tool for establishing a quick diagnosis. It typically shows mixed flora (with many neutrophils) in anaerobic infection or one predominant gram-positive or -negative organism (with neutrophils present) in aerobic infection. Cultures usually grow normal respiratory flora in polymicrobial anaerobic infection or grow the infecting organism in aerobic infection.

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated while cultures are pending in cases with typical clinical presentations and radiologic findings.

Blood

All patients should undergo routine blood cultures. These are positive for the infecting organism in aerobic infections, bacteremia, and septic embolism, but they are seldom positive in anaerobic infections.

Lower airway secretions

Uncontaminated lower airway specimens should be obtained for anaerobic culture when the early response to treatment is poor.[11][14] Techniques include transtracheal needle aspiration, transthoracic aspiration, and bronchoscopic protected specimen brushings or protected bronchoalveolar lavage. Quantitative cultures are usually considered diagnostic of infection if protected specimen brushings grow >1000 colony-forming units/mL or if protected bronchoalveolar lavage samples growth >10,000 colony-forming units/mL.[28] However, these techniques are seldom required in routine clinical practice.

Ultrasound- or CT-guided percutaneous needle aspiration has a significantly higher yield than samples obtained from sputum, blood, or bronchoalveolar lavage and can establish a bacteriologic diagnosis when cultures are inconclusive from other samples.[29][30] Serious complications include pneumothorax and bacterial contamination, which may cause empyema. Furthermore, ultrasound-guided needle biopsy is only possible when the abscess is subpleural with no normal lung between the abscess and chest wall. Given the complications and limitations of the method, a careful risk-benefit analysis is always required.

Empyema fluid

Thoracocentesis with culture of the empyema fluid should be performed in patients with an empyema. Cultures may be negative in polymicrobial anaerobic infection, but they may grow the infecting organism in aerobic infection.

Other investigations

Chest CT scan

Contrast-enhanced CT scan (venous “pleural” phase) is a more sensitive imaging modality than chest x-ray. It can identify proximal endobronchial obstruction (e.g., an inhaled foreign body) and distinguish between lung abscess and empyema.[9][31][32] A lung abscess appears as a thick-walled, usually round, cavity with irregular margins that forms an acute angle where contact is made with the chest wall, but it does not compress the surrounding lung.[9] By contrast, empyema appears lenticular in shape, has a thin wall with smooth luminal margins and a smooth exterior wall, forms obtuse angles with the chest wall, and may compress the uninvolved lung. Separate pleural layers (the split pleura’ sign) may also seen in empyema.[9][31][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT of thorax showing a lung abscessFrom the collection of Dr Ioannis P. Kioumis [Citation ends].

Bronchoscopy

Indicated when an underlying carcinoma or foreign body obstruction is clinically suspected, treatment response is poor, or sputum analysis is inconclusive. It can be used for specimen collection (protected specimen brushings or protected bronchoalveolar lavage).[33][34]

Underlying malignancy is clinically suspected in cases with a low-grade fever, leukocyte count <11,000/microliter, minimal systemic complaints, no factors predisposing to aspiration, nonresponse to antibiotics by day 10, and a deteriorating course.[26]

Sputum cytology

This may show malignant cells. Indicated to exclude malignancy in patients who do not respond to antibiotics or present with hemoptysis.

Lung ultrasound

In addition to being used to guide percutaneous needle aspiration, lung ultrasound is a useful tool for bedside diagnosis in critically ill patients.[29] It can reveal a hypoechoic lesion with an irregular outer wall and a cavity, which appears as a hyperechoic ring.[29]

Echocardiogram

Performed for patients with a lung abscess suspected to be secondary to septic embolism from right-sided (e.g., tricuspid valve) bacterial endocarditis. It reveals vegetations on the affected valve.

Rapid enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for D-dimer

Performed for patients with a lung abscess suspected to be secondary to infection from an infarct related to a pulmonary embolism. It is elevated in pulmonary embolism. Care should be taken when interpreting the result, as several conditions (including infection) may raise the D-dimer.

Multidetector CT (MDCT)

Performed for patients with a lung abscess suspected to be secondary to infection from an infarct related to a pulmonary embolism. Thoracic MDCT shows intraluminal filling defects in pulmonary embolism.

Ventilation-perfusion (VQ) scan

Performed for patients with a lung abscess suspected to be secondary to infection from an infarct related to a pulmonary embolism. It reveals perfusion defects in areas with normal ventilation.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer