Urgent considerations

See Differentials for more details

All patients who are critically ill or deteriorating should be assessed using the Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure (ABCDE) approach.[12][13] The clinician should make a rapid assessment of the airway in any patient with dyspnea and take any necessary measures to ensure the airway is secure. These measures may include repositioning the patient and/or making use of nasal or oral airways as appropriate.

How to select the correct size naspharyngeal airway and insert the airway device safely.

How to size and insert an oropharygeal airway.

Consultation with an anesthetist may be advisable for patients with extreme dyspnea.

Pulse oximetry or arterial blood gases should be used to assess oxygenation, and supplemental oxygen should be administered if required. If the patient is critically unwell, high-flow oxygen should be administered initially, pending further investigations. Once reliable pulse oximetry is available, the UK guidelines recommend that oxygen should be prescribed to achieve a target saturation of 94% to 98% for most acutely ill patients or 88% to 92% (or patient-specific target range) for those at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure.[14] Guidelines on specific disorders from different organizations may vary in their recommendations concerning supplemental oxygen and target ranges. One systematic review and meta-analysis found that liberal use of oxygen was associated with increased mortality in acutely ill patients compared with a conservative oxygen strategy.[15][16]

Sudden onset of severe dyspnea or dyspnea at rest should prompt an inquiry regarding chest pain and whether the patient has a medical history of coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or asthma.

Initial responses to questions, findings from the ABCDE examination, and clinical observations may help to confirm the most likely diagnosis, and urgent further investigations and treatments may then be tailored to the most likely diagnoses.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

COVID-19 is a potentially severe acute respiratory infection caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The clinical presentation is typically with fever, cough, dyspnea, and/or fatigue. Patients may develop a severe viral pneumonia leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome that is potentially fatal. Severe illness is associated with older age and the presence of underlying health conditions.

Patients with suspected COVID-19 infection should be isolated from other patients. Contact and droplet precautions should be implemented until the patient is asymptomatic.

See our Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) topic for current management advice.

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS)

Typically presents with central chest pain radiating to the shoulders and neck and is frequently accompanied by dyspnea. However, atypical presentations such as dyspnea without pain, or with atypical pain, may occur, especially in women, people with diabetes, and people ages over 75 years.[17][18][19] Dyspnea accompanying acute coronary disease has a negative prognostic significance.[20]

The patient may be clammy, pale and hypotensive. Clinical examination is often normal, however an S3 or S4 gallop rhythm may be present on cardiac auscultation, and pulmonary exam may reveal pulmonary rales. Presence of characteristic ECG changes, along with biochemical evidence of myocardial injury (elevated cardiac enzymes), helps establish the diagnosis.[21][22] ACS has been divided into three clinical categories as follows:

ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI): ECG shows persistent ST-segment elevation in two or more anatomically contiguous leads, or new left bundle-branch block.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: 12-Lead ECG showing inferior and anterior ST-elevation with reciprocal changes in the lateral leadsFrom the personal collection of Dr Mahi Ashwath; used with permission [Citation ends].

Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI): ECG does not show ST-segment elevation, but cardiac biomarkers are elevated. The ECG may show nonspecific ischemic changes such as ST-segment depression or T-wave inversion.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG showing ST depressionFrom the personal collection of Dr Syed W. Yusuf and Dr Iyad N. Daher, Department of Cardiology, University of Texas, Houston; used with permission [Citation ends].

Unstable angina pectoris: nonspecific ischemic ECG changes, but cardiac biomarkers are normal.

Timely clinical and electrocardiographic assessment is critical in making a diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome.

In cases of STEMI, prompt revascularization (via percutaneous coronary intervention or, if this is not available, fibrinolysis) improves survival. Aspirin and other antiplatelet agents, beta-blockers, nitrates, and anticoagulants are used as initial treatment in different forms of ACS.

Acute asthma

Acute-onset dyspnea, especially in a person with a history of asthma, may indicate the presence of an acute asthma attack. This typically presents with progressively worsening wheeze and cough, although in severe cases wheeze may be absent. The British Thoracic Society guidelines define acute severe asthma according to the presence of any of the following features: peak expiratory flow 33% to 50% best or predicted, respiratory rate ≥25/min, heart rate ≥110/min or, inability to complete sentences in one breath.[23] Severe asthma is considered life-threatening if any of the following are present:

Altered conscious level

Exhaustion

Arrhythmia

Hypotension

Cyanosis

Silent chest

Poor respiratory effort

Peak expiratory flow <33% best or predicted

Oxygen saturations <92%

PaO2 <8kPa

PaCO2 in normal range (4.6 - 6.0 kPa)

If the patient has signs of a severe exacerbation, arrange emergent transfer to the emergency department, or to intensive care if the patient is drowsy, confused, or has a silent chest.[24] Careful monitoring is essential.[24]

Initial treatment is with titrated supplementary oxygen, high-dose inhaled short-acting beta 2 agonist bronchodilators, corticosteroids (in adequate doses), and sometimes, intubation with mechanical ventilation.[23][24] Ipratropium should only be used for severe exacerbations; intravenous magnesium sulfate may be considered if patients are unresponsive to initial therapy.[23][24]

Severe acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Acute exacerbations of COPD typically present with an increased level of dyspnea, worsening chronic cough, and/or an increase in the volume and/or purulence of sputum produced. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defines a COPD exacerbation as an "event characterized by dyspnea and/or cough and sputum that worsens over <14 days".[25] Use of accessory respiratory muscles, paradoxical respirations, cyanosis, new peripheral edema, hemodynamic instability, and/or worsened mental status (e.g., confusion, lethargy, coma) are important indicators of severity of an exacerbation. Patients with life-threatening exacerbations require management in an intensive care setting.

Initial treatment of severe, but not life-threatening, exacerbations includes short-acting beta-2 agonists with short-acting anticholinergic medicines, supplemental oxygen if the patient is hypoxic (although oxygen should be applied with caution to prevent further hypercapnia), systemic corticosteroids, and antibiotics if bacterial infection is a suspected trigger.

Patients with severe exacerbations who do not appear to respond sufficiently to initial interventions should be considered for noninvasive ventilation (NIV). NIV is recommended as the first type of ventilation to consider in people with acute respiratory failure and COPD, providing there are no contraindications.[25] The GOLD 2025 report includes indications for NIV and for invasive ventilation in people presenting with acute exacerbation of COPD.[25]

Anaphylaxis

Systemic anaphylactic reactions may result when a predisposed host is exposed to a medication, food, or insect sting or bite. Sudden-onset dyspnea is accompanied by cutaneous manifestations (rash, itching, urticaria, angioedema), voice changes, a choking sensation, tongue and facial edema, wheezing, tachycardia, and hypotension. Occasionally, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea may be present.

Diagnosis is made on clinical grounds. Prompt treatment by removal of the inciting antigen, immediate administration of intramuscular epinephrine to the anterolateral thigh, airway management, and volume resuscitation can be lifesaving.[26][27][28]

Foreign body aspiration

History of epilepsy, syncope, altered mental status (e.g., intoxication, hypoglycemia), or choking and coughing after ingesting food (particularly nuts) may suggest foreign body aspiration. If the airway has a small size as in children and adolescents, and the foreign body lodges in the hypopharynx or glottis, it may cause a life-threatening obstruction that may lead to asphyxiation.

Cyanosis and stridor followed by hypotension and circulatory collapse may ensue. Initial management of the conscious adult or child includes back blows, followed by abdominal thrust if back blows are unsuccessful. Back blows, followed by chest thrusts are recommended for conscious infants; do not use abdominal thrusts in infants.[29] In the medical setting, removing the foreign body may be attempted, while orotracheal intubation or cricothyroidotomy provides acute airway management.

Lung cancer

Cough and dyspnea are the most common symptom of lung cancer and may be accompanied by weight loss, hemoptysis, chest pain, or hoarseness.[30] Current or prior smoking is the most significant risk factor for lung cancer. Diagnosis is confirmed by radiography and pathology, and treatment may involve surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. Acute presentations requiring urgent management include massive hemoptysis, post-obstructive pneumonia/hypoxia, and superior vena cava syndrome. A patient with massive hemoptysis should be immediately placed with the presumed bleeding lung (if known) in the dependent position. Selective intubation of the nonbleeding main stem bronchus, or a double lumen intubation, may be required to secure the airway. Flexible bronchoscopy or arteriographic techniques are used to definitively control the bleeding.[31]

Post-obstructive pneumonia due to a proximal lung tumor can be initially treated by securing the airway, followed by a range of local (interventional or rigid bronchoscopy) or external (external beam radiation) treatment modalities.[32]

Superior vena cava syndrome due to malignant obstruction may present with neck and facial swelling, chest pain, cough, dilated collateral chest veins, and facial plethora in addition to dyspnea.[33] Superior vena cava syndrome initially managed by placement of the venous stent or radiation therapy.[32][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Prominent collateral vein on the anterior chest and abdominal wall in a patient with superior vena cava syndrome.From the collection of E Kempny. Reproduced under the Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/) [Citation ends].

Upper airway obstruction

This may be caused by a foreign body; an airway tumor on the base of the tongue, larynx, esophagus, or trachea; edema; dysfunction of upper airway structures (e.g., vocal cord dysfunction, angioedema); and extrinsic compression (e.g., subglottic stenosis, retrosternal goiter, lymphoma).

These conditions are typically accompanied by significant dyspnea, inspiratory stridor, and occasionally expiratory wheezing, all of which are exacerbated by exercise-induced increases in flow through the airway.

Immediate management involves establishing a secure airway, as well as investigating and treating the underlying cause with radiographic and bronchoscopic techniques.

Epiglottitis

Epiglottitis is a cellulitis of the supraglottis that may cause airway compromise. It is an airway emergency and precautionary measures must be taken.

Epiglottitis is classically described in children aged 2 to 6 years of age; however, it may manifest at any age, including in newborns.

It is characterized by a rapidly progressive sore throat, fever, odynophagia, dysphonia, drooling, hoarseness and stridor. Tripod positioning, where the child sits upright, extends the head and neck and places the hands on the knees is classic.

No action should be taken that could stimulate a child with suspected epiglottitis, including examination of the oral cavity, starting intravenous lines, blood draws, or even separation from a parent, because crying may exacerbate the airway obstruction.

Diagnosis is made on clinical grounds and laboratory or other interventions should not preclude or delay timely control of the airway in a suspected case of epiglottitis.

Once the airway has been secured and antibiotics have been initiated, the condition usually resolves rapidly.

Severe pneumonia

Clinical diagnosis of pneumonia is based on a group of signs and symptoms related to lower respiratory tract infection. Symptoms may include dyspnea, fever >100ºF (>38ºC), cough, expectoration, and chest pain, while the signs of crepitations, reduced chest expansion, asymmetric breath sounds and increased vocal fremitus indicate consolidation of the alveolar space. Older patients, in particular, are often afebrile and may present with confusion and worsening of underlying diseases. The presence of afebrile bacteremia in a patient with pneumonia is associated with an increased mortality.[34] Various scoring systems for assessing severity are available, including the pneumonia severity index (PSI) and the CURB-65 for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), with increasing scores associated with increasing mortality.[35][36] [ Community-acquired pneumonia severity index (PSI) for adults Opens in new window ] [ CURB-65 pneumonia severity score Opens in new window ]

Hospital treatment is recommended for people with suspected CAP with:[35][37][38][39]

PSI Score of 71 to 90 (class III; who may benefit from a brief period of hospitalization)

PSI Score of 91 to 130 (class IV) or >130 (class V; with a 9% and a 27% risk of death, respectively)

CURB-65 Score of ≥3 (mortality risk exceeds 15% and patients may require ICU admission). Patients with a score of 2 or more may need hospital treatment

Hypoxemia (all patients presenting with SaO₂ <90% or PaO₂ <60 mmHg) or serious hemodynamic instability (who should be hospitalized regardless of their severity score)

Suppurative or metastatic disease

Medical or psychosocial contraindications to outpatient therapy, e.g., inability to maintain oral intake, history of substance misuse, cognitive impairment, severe comorbid illnesses, impaired functional status.

Hospitalized patients should receive appropriate oxygen therapy, with monitoring of oxygen saturation and inspired oxygen concentration, with the aim of maintaining SaO₂ above 94%. Oxygen therapy in patients with COPD that is complicated by ventilatory failure should be guided by repeated arterial blood gas measurements.[40] Patients with respiratory failure, despite appropriate oxygen therapy, require urgent airway management and possible intubation. Patients should be assessed for volume depletion, and intravenous fluids should be administered if needed. Nutritional support should be given in prolonged illness.[40] Empiric antibiotics for CAP should follow international guidelines and local epidemiology.

Sepsis

Sepsis is a spectrum of disease, where there is a systemic and dysregulated host response to an infection.[41] Presentation ranges from subtle, nonspecific symptoms (e.g., feeling unwell with a normal temperature) to severe symptoms with evidence of multiorgan dysfunction and septic shock. Patients may have signs of tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, fever or hypothermia, poor capillary refill, mottled or ashen skin, cyanosis, newly altered mental state, or reduced urine output.[42] Sepsis and septic shock are medical emergencies.

Risk factors for sepsis include: age under 1 year, age over 75 years, frailty, impaired immunity (due to illness or drugs), recent surgery or other invasive procedures, any breach of skin integrity (e.g., cuts, burns), intravenous drug misuse, indwelling lines or catheters, and pregnancy or recent pregnancy.[42]

Early recognition of sepsis is essential because early treatment improves outcomes.[42][43][Evidence C][Evidence C] However, detection can be challenging because the clinical presentation of sepsis can be subtle and non-specific. A low threshold for suspecting sepsis is therefore important. The key to early recognition is the systematic identification of any patient who has signs or symptoms suggestive of infection and is at risk of deterioration due to organ dysfunction. Several risk stratification approaches have been proposed. All rely on a structured clinical assessment and recording of the patient’s vital signs.[42][44][45][46][47] It is important to check local guidance for information on which approach your institution recommends. The timeline of ensuing investigations and treatment should be guided by this early assessment.[46]

Treatment guidelines have been produced by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign and remain the most widely accepted standards.[43][48] Recommended treatment of patients with suspected sepsis is:

Measure lactate level and remeasure lactate if initial lactate is elevated (>18 mg/dL [>2 mmol/L])

Obtain blood cultures before administering antibiotics

Administer broad-spectrum antibiotics (with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA] coverage if there is high risk of MRSA) for adults with possible septic shock or a high likelihood for sepsis

For adults with sepsis or septic shock at high risk of fungal infection, empiric antifungal therapy should be administered

Begin rapid administration of crystalloid fluids for hypotension or lactate level ≥36 mg/dL (≥4 mmol/L). Consult local protocols.

Administer vasopressors peripherally if hypotensive during or after fluid resuscitation to maintain MAP ≥65 mm Hg, rather than delaying initiation until central venous access is secured. Norepinephrine (noradrenaline) is the vasopressor of choice.

For adults with sepsis-induced hypoxemic respiratory failure, high flow nasal oxygen should be given.

Ideally, these interventions should all begin in the first hour after sepsis recognition.[48]

For adults with possible sepsis without shock, if concern for infection persists, antibiotics should be given within three hours from the time when sepsis was first recognized.[43] For adults with a low likelihood of infection and without shock, antibiotics can be deferred while continuing to closely monitor the patient.[43]

For more information on the diagnosis and management of sepsis see Sepsis in adults and Sepsis in children.

Acute pulmonary embolism

Severe pulmonary embolism (PE) may present with sudden dyspnea and chest pain, associated with tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, hypoxemia, and neck vein engorgement. Chest pain may be pleuritic if a distal area of the lung is infarcted, which causes pleural irritation. Central emboli may cause central chest pain similar to ACS, possibly due to right ventricle ischemia.[49]

Thrombi originating from the deep venous system of the lower extremities and pelvic veins are the most common etiologies. Other endogenous or exogenous material that gains access to the venous bed such as fat, air, amniotic fluid, tumor material, vertebroplasty cement, silicone, inferior vena cava filters, or intracardiac devices may less commonly cause PE.[50][51][52][53]

Previous venothromboembolic disease, inadequate anticoagulation, immobilization, admission to the hospital, travel, vascular access, or leg injury may predispose the patient to develop a PE.

Computed tomographic (CT) pulmonary angiography of the chest is the best investigation for diagnosing and excluding PE. In patients undergoing diagnostic evaluation awaiting confirmation of PE, supportive therapies and empiric anticoagulation (unless contraindicated) should be instituted without delay.[54][55]

Pneumothorax

Sudden-onset dyspnea associated with unilateral chest pain may indicate acute pneumothorax. Spontaneous pneumothorax can occur in tall asthenic people secondary to pleural blebs, or in those who smoke crack cocaine.[56][57] It may also be seen in HIV infection. Secondary pneumothorax may complicate pre-existing lung disease such as COPD and lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

If a ball-valve mechanism develops (i.e., tension pneumothorax), air fills the pleural space, compresses the lung, and shifts the mediastinum. This may result in cardiorespiratory collapse, a medical emergency requiring prompt recognition and treatment. On examination, breath sounds are unilaterally absent, and percussion of the ipsilateral chest may reveal tympany. The trachea may also be deviated away from the lesion.

A tension pneumothorax is a medical emergency. Treatment consists of immediate decompression of the pneumothorax by placing a large-bore needle into the second intercostal space at the midclavicular line, the fourth intercostal space between the midaxillary and anterior axillary line, or the fifth intercostal space between the midaxillary and anterior axillary line. This decompression acts as a bridge to tube thoracostomy, the definitive treatment. The dynamic development of tension pneumothorax does not allow time for any additional testing, but in nontension pneumothorax a chest x-ray shows partial or total collapse and unilateral lucidity.[58]

How to decompress a tension pneumothorax. Demonstrates insertion of a large-bore intravenous catheter into the fourth intercostal space in an adult.

Acute valvular insufficiency

If due to rupture of the papillary muscle or chordae tendinae, acute valvular insufficiency typically occurs a few days after an acute myocardial infarction as a result of ischemic changes to the mitral valve apparatus. It may less commonly result from endocarditis-related leaflet rupture.[62]

It presents with acute dyspnea, accompanied by a systolic murmur and signs of acute cardiovascular collapse with hypotension, tachycardia, and pulmonary rales. Although acute valvular insufficiency can be frequently suspected on clinical grounds, an echocardiogram is typically required to establish the diagnosis.[63]

Urgent cardiovascular surgery consultation is required while the patient is stabilized with the use of vasodilators, occasionally used in combination with pressors, inotropes, and fluids. Temporary mechanical circulatory assist device or intraaortic balloon counterpulsation can be used as the patient awaits surgical therapy.[64] Even with these measures, the expected mortality in a patient with acute valvular insufficiency is high.

Acute exacerbation of congestive heart failure

Acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema results from increased end-diastolic left ventricular pressure and presents with dyspnea worsened by exertion, orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, elevated neck veins, peripheral fluid retention, an S3 gallop rhythm on cardiac auscultation, and pulmonary congestion (fine bibasal rales) on chest auscultation. The patient may have a history of heart failure.

Typical chest x-ray features include characteristic signs of pulmonary venous congestion, and there may be cardiomegaly.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray of acute pulmonary edema showing increased alveolar markings, fluid in the horizontal fissure, and blunting of the costophrenic anglesFrom the private collections of Syed W. Yusuf, MBBS, MRCPI, and Daniel Lenihan, MD [Citation ends].

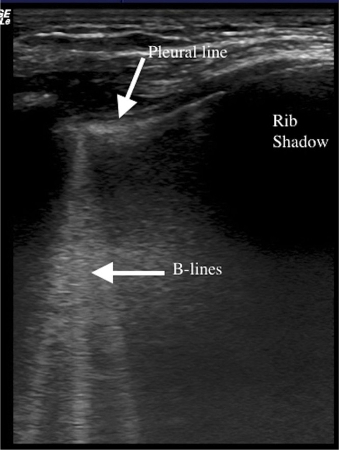

Echocardiography may show atrial fibrillation and enables differentiation between systolic and diastolic heart failure, and estimation of left ventricular ejection fraction. Bedside ultrasound study showing B-lines strongly suggests acute pulmonary edema in an appropriate clinical setting.[65][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lung ultrasonography scan of a single intercostal space showing B-lines (white vertical lines) - curved arrayWimalasena Y, Kocierz L, Strong D, et al. Lung ultrasound: a useful tool in the assessment of the dyspnoeic patient in the emergency department. Fact or fiction? Emerg Med J. 2017 Mar 3. pii. [Citation ends].

A low B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level (<100 picograms/mL) or a low N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP) level (<300 nanograms/L [<300 picograms/mL]) is helpful in excluding congestive heart failure.[66]

Depending on the specific etiology of congestive heart failure, a combination of diuretic, preload and afterload reduction with nitrates, ACE inhibitors, and noninvasive mechanical ventilation can be used.

Aortic dissection

Aortic dissection more commonly affects middle-aged and older men, those with preexisting valvular heart disease (such as bileaflet aortic valve or coarctation of the aorta), and patients with collagen disorders (such as Marfan syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome). It typically presents with dyspnea and severe chest pain that may radiate to the back. It may be accompanied by hypotension. Examination of the peripheral vascular system may demonstrate absent peripheral pulses, or differences in blood pressure measurements between upper and lower extremities.

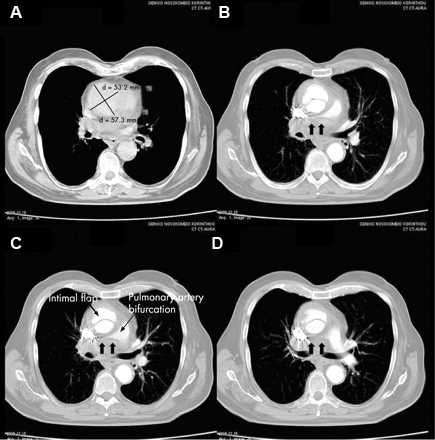

Ascending aortic dissection should be suspected with widening of the mediastinum on chest x-ray, although this sign is only present in about 50% of patients.[67] Emergency echocardiogram or CT chest angiography is used to confirm diagnosis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT of a 71-year-old man showing type II dissecting aneurysm of the ascending aorta. Haematoma around the proximal segment of the ascending aorta (panels A-D) compressed the right pulmonary artery, almost occluding its patency and limiting the perfusion of the reciprocal lungStougiannos PN, Mytas DZ, Pyrgakis VN. The changing faces of aortic dissection: an unusual presentation mimicking pulmonary embolism. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2006.104414 [Citation ends].

Management of aortic dissection depends on the site of dissection. While type A (ascending aortic) dissections constitute a surgical emergency, type B (descending aortic) dissections are initially treated medically. Surgical intervention in type B dissection is reserved for those who do not respond to medical management. Endovascular treatment options are gaining popularity in the initial management of type B dissections.[68][69]

Pericardial tamponade

Acute pericardial tamponade may complicate an acute myocardial infarction, with left ventricular wall rupture, or result from coronary artery rupture, aortic dissection, or injury from a pacemaker wire. Dyspnea may be accompanied by neck vein and facial engorgement, shock, peripheral cyanosis, and tachycardia.

Diagnosis is suggested by an enlarged cardiac silhouette on chest x-ray and the ECG findings of low-voltage and depression of the PR segment, and is established by echocardiography.[9][70] Treatment is with urgent pericardiocentesis and/or surgical intervention.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pericardial tamponade: admission chest x-rayUsalan C, Atalar E, Vural FK. Pericardial tamponade in a 65-year-old woman. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:183-184; used with permission. [Citation ends].

Pulmonary contusion

Both pulmonary contusion and hemothorax may result from blunt (e.g., motor vehicle accident, fall) or penetrating (e.g., stab and gunshot wounds) trauma. In pulmonary contusion, implosion or inertia forces tear the alveolar tissue, resulting in pulmonary hemorrhage, pulmonary edema, and the appearance of patchy or more confluent infiltrates on chest x-ray or CT of the chest. Treatment is supportive, with adequate monitoring, oxygen supplementation, and pulmonary toilet.[71]

Owing to the large potential volume of blood that may collect in the pleural space, hemothorax may present with dyspnea, circulatory collapse, and shock. Diagnosis is established by chest x-ray and confirmed by sampling the pleural fluid. Treatment consists of volume repletion and drainage of the pleural space using a large-bore thoracostomy tube. Thoracic surgery evaluation may be required for persistent drainage.

Bradyarrhythmia

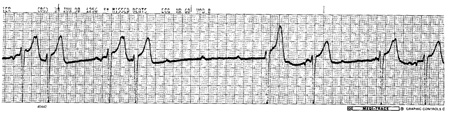

Severe bradyarrhythmias, including complete heart block, with the development of a slow escape rhythm may present as dyspnea with weakness, lightheadedness, or syncope. ECG diagnosis is followed by ruling out reversible causes (e.g., acute anterior or inferior myocardial infarction, medications, electrolyte disturbances, hypothyroidism, or adrenal insufficiency) and implanting a pacemaker.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG showing complete atrioventricular (AV) blockFrom the collection of Brian Olshansky, MD, FAHA, FACC, FHRS; used with permission [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer