Children presenting with fever of unknown origin or urinary symptoms should be promptly evaluated for a diagnosis of UTI.[39]Shaikh N, Morone NE, Lopez J, et al. Does this child have a urinary tract infection? JAMA. 2007 Dec 26;298(24):2895-904.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18159059?tool=bestpractice.com

The general diagnostic approach to pediatric UTIs is differentiated by:

Infection may involve the upper or lower urinary tract; be complicated or uncomplicated; severe or nonsevere; recurrent, breakthrough, or a reinfection; atypical, asymptomatic, or symptomatic. See Classification for more information.

Neonates and infants ages ≤2 months are at high risk for serious bacterial infection and sepsis.[1]European Association of Urology. Guidelines on paediatric urology. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/paediatric-urology/chapter/introduction

[40]Robinson JL, Finlay JC, Lang ME, et al. Urinary tract infections in infants and children: diagnosis and management. Paediatr Child Health. 2014 Jun;19(6):315-25.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4173959

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25332662?tool=bestpractice.com

Symptoms are nonspecific in this age group, making it difficult to distinguish UTI from other causes of serious bacterial infection at initial evaluation.[41]Kaufman J, Temple-Smith M, Sanci L. Urinary tract infections in children: an overview of diagnosis and management. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2019 Sep 24;3(1):e000487.

https://bmjpaedsopen.bmj.com/content/3/1/e000487

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31646191?tool=bestpractice.com

These children should be admitted to hospital for evaluation and most should receive empiric parenteral antibiotic therapy. See Sepsis in children for more information.

Children ages >2 months may first have urinalysis via dipstick testing, microscopy, or, if available, flow cytometry.[1]European Association of Urology. Guidelines on paediatric urology. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/paediatric-urology/chapter/introduction

Diagnosis and treatment are often concurrent processes. Empiric therapy may be commenced before diagnostic assessment is completed if there is a high risk of serious illness. Further investigation may depend on response to initial therapy.

History

The history may reveal risk factors that are strongly associated with UTI, such as age <1 year, female sex or uncircumcised infant boy, previous history of UTI, bladder bowel dysfunction, vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), and instrumentation of the urinary tract.[5]Mattoo TK, Shaikh N, Nelson CP. Contemporary management of urinary tract infection in children. Pediatrics. 2021 Feb;147(2):e2020012138.

https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/147/2/e2020012138/36243/Contemporary-Management-of-Urinary-Tract-Infection

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33479164?tool=bestpractice.com

Neonates often present with very nonspecific symptoms such as an undifferentiated febrile illness, irritability, vomiting, or poor feeding.[7]Becknell B, Schober M, Korbel L, et al. The diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of acute and recurrent pediatric urinary tract infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015 Jan;13(1):81-90.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4652790

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25421102?tool=bestpractice.com

A generally ill appearance, mottling, unstable vital signs, decreased activity, and poor oral intake indicate that they may have sepsis. Less commonly, neonates with a urinary tract infection can present with late-onset jaundice or faltering growth.

In infants and toddlers the presentation is also likely to be nonspecific, including fever, diarrhea, or vomiting with dehydration, or faltering growth. Urinary symptoms in this age group include abdominal/flank pain, foul-smelling urine, and new-onset urinary incontinence.[7]Becknell B, Schober M, Korbel L, et al. The diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of acute and recurrent pediatric urinary tract infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015 Jan;13(1):81-90.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4652790

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25421102?tool=bestpractice.com

Even with serious bacterial infection, signs and symptoms may be subtle.

In older (verbal) children and adolescents, symptoms and signs may be more specific to the urinary system, and include dysuria, foul-smelling urine, urgency, frequency, new-onset urinary incontinence, or gross hematuria.[7]Becknell B, Schober M, Korbel L, et al. The diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of acute and recurrent pediatric urinary tract infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015 Jan;13(1):81-90.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4652790

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25421102?tool=bestpractice.com

Systemic symptoms such as fever, abdominal or flank pain, and vomiting are highly suggestive of pyelonephritis.

Enquire about sexual activity in adolescents. Sexual intercourse increases the risk of UTI in females. Symptoms of urethritis caused by sexually transmitted infections may mimic UTI in both sexes.

Physical exam

The physical exam is useful to detect signs of urinary tract infection and exclude other possible causes for the patient's symptoms.

A full physical exam is indicated in infants and febrile patients.

In older patients, the abdomen and genitalia should be examined, and the costovertebral angles should be palpated. Palpable bladder or abdominal mass, poor urinary flow, poor growth, and elevated blood pressure may be seen with obstructive uropathy or chronic kidney disease and should prompt the clinician to consider abnormalities of the urinary tract.

Vaginal irritation or discharge may be seen with vaginitis (including irritant vaginitis) and may identify the reproductive tract, rather than the urinary tract, as the source of symptoms, particularly in infants and toddlers. Labial adhesions in girls and severe phimosis in boys can predispose recurrent UTIs.

Initial investigations

Urinalysis

Initial test in symptomatic children ≥2 months.

The urine sample should be collected as soon as possible, ideally at the consultation. If this is not possible, a sample should be collected and returned within 24 hours.[4]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary tract infection in under 16s: diagnosis and management. Jul 2022 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng224

Urine samples should be taken before any antibiotic treatment is initiated, unless there is high risk of serious illness.[4]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary tract infection in under 16s: diagnosis and management. Jul 2022 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng224

The urine sample is analyzed either by urine dipstick, microscopy, or, if available, flow cytometry.[1]European Association of Urology. Guidelines on paediatric urology. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/paediatric-urology/chapter/introduction

Urine is examined for evidence of pyuria (positive leukocyte esterase/presence of white blood cells on microscopy) and/or bacteriuria (positive nitrites/bacteria visible after Gram stain).

Possible dipstick results are as follows.

Positive for leukocyte esterase and nitrite: positive likelihood ratio (LR+) 28.2.[42]Whiting P, Westwood M, Watt I, et al. Rapid tests and urine sampling techniques for the diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) in children under five years: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2005 Apr 5;5(1):4.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1084351

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15811182?tool=bestpractice.com

This test is best at ruling in disease, with the best yield in children >2 years of age.[43]Mori R, Yonemoto N, Fitzgerald A, et al. Diagnostic performance of urine dipstick testing in children with suspected UTI: a systematic review of relationship with age and comparison with microscopy. Acta Paediatr. 2010 Apr;99(4):581-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20055779?tool=bestpractice.com

Positive for either leukocyte esterase or nitrite: sensitivity 92%, negative likelihood ratio (LR-) 0.2.[42]Whiting P, Westwood M, Watt I, et al. Rapid tests and urine sampling techniques for the diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) in children under five years: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2005 Apr 5;5(1):4.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1084351

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15811182?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Downs SM. Technical report: urinary tract infections in febrile infants and young children. Pediatrics. 1999 Apr;103(4):e54.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10103346?tool=bestpractice.com

This test is best at ruling out disease.

Positive nitrite alone: sensitivity 58%, specificity 99%, LR+ 15.9, LR- 0.51.[42]Whiting P, Westwood M, Watt I, et al. Rapid tests and urine sampling techniques for the diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) in children under five years: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2005 Apr 5;5(1):4.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1084351

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15811182?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Downs SM. Technical report: urinary tract infections in febrile infants and young children. Pediatrics. 1999 Apr;103(4):e54.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10103346?tool=bestpractice.com

This test has a high positive predictive value. In children of all ages, nitrites are highly specific for UTI.[45]Coulthard MG. Using urine nitrite sticks to test for urinary tract infection in children aged <2 years: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019 Jul;34(7):1283-8.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6531406

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30895368?tool=bestpractice.com

Nitrites are formed by conversion of urinary nitrates to nitrites by gram-negative bacteria. In children ages <2 years, the sensitivity of nitrites is particularly low (23%).[45]Coulthard MG. Using urine nitrite sticks to test for urinary tract infection in children aged <2 years: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019 Jul;34(7):1283-8.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6531406

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30895368?tool=bestpractice.com

Formation of nitrites by bacteria requires urine to be held in the bladder for 4 to 6 hours, and young children usually void more frequently than this.[46]Powell HR, McCredie DA, Ritchie MA. Urinary nitrite in symptomatic and asymptomatic urinary infection. Arch Dis Child. 1987 Feb;62(2):138-40.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1778270

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3548604?tool=bestpractice.com

Nitrites will not be present in infections with enterococcal or staphylococcal species. Therefore, the absence of nitrites does not exclude UTI.

Positive leukocyte esterase alone: sensitivity 84%, specificity 77%, LR+ 5.5, LR- 0.26.[42]Whiting P, Westwood M, Watt I, et al. Rapid tests and urine sampling techniques for the diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) in children under five years: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2005 Apr 5;5(1):4.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1084351

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15811182?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Downs SM. Technical report: urinary tract infections in febrile infants and young children. Pediatrics. 1999 Apr;103(4):e54.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10103346?tool=bestpractice.com

Negative for leukocyte esterase and nitrite: an alternative cause for the patient’s symptoms should be sought. However, false negatives may occur if the patient has been exposed to antibiotics; in this instance a sample should be sent for culture.

Possible microscopy results are as follows.

Pyuria (the presence of white blood cells [WBCs]): sensitivity 78%, specificity 87%; LR- 0.27.[42]Whiting P, Westwood M, Watt I, et al. Rapid tests and urine sampling techniques for the diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) in children under five years: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2005 Apr 5;5(1):4.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1084351

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15811182?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Downs SM. Technical report: urinary tract infections in febrile infants and young children. Pediatrics. 1999 Apr;103(4):e54.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10103346?tool=bestpractice.com

Significant pyuria is ≥10 WBCs/mm³ on an enhanced urinalysis or ≥5 WBCs per high-power field on a centrifuged specimen of urine. The optimal cut point for diagnosing pyuria varies according to urine concentration in children ages <24 months, from 3 WBCs per high-power field in dilute urine to 8 WBCs per high-power field in concentrated urine.[47]Nadeem S, Badawy M, Oke OK, et al. Pyuria and urine concentration for identifying urinary tract infection in young children. Pediatrics. 2021 Feb;147(2):e2020014068.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33514634?tool=bestpractice.com

Other inflammatory conditions, or the presence of renal stones, may cause pyuria in the absence of UTI.[13]Schmidt B, Copp HL. Work-up of pediatric urinary tract infection. Urol Clin North Am. 2015 Nov;42(4):519-26.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4914380

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26475948?tool=bestpractice.com

Bacteriuria: sensitivity 88%, specificity 93%, LR+ 14.7, LR- 0.19.[42]Whiting P, Westwood M, Watt I, et al. Rapid tests and urine sampling techniques for the diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) in children under five years: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2005 Apr 5;5(1):4.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1084351

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15811182?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Downs SM. Technical report: urinary tract infections in febrile infants and young children. Pediatrics. 1999 Apr;103(4):e54.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10103346?tool=bestpractice.com

Presence of any bacteria on microscopy indicates bacteriuria. Morphology and gram-staining characteristics may aid early identification of the causative organism.

Flow cytometry is performed on uncentrifuged specimens and provides counts of WBCs and bacteria in the urine.[1]European Association of Urology. Guidelines on paediatric urology. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/paediatric-urology/chapter/introduction

Studies suggest that this technique may have a greater sensitivity and specificity in children than dipstick testing or microscopy; however, it is not yet widely available.[48]Boonen KJ, Koldewijn EL, Arents NL, et al. Urine flow cytometry as a primary screening method to exclude urinary tract infections. World J Urol. 2013 Jun;31(3):547-51.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22588552?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Broeren M, Nowacki R, Halbertsma F, et al. Urine flow cytometry is an adequate screening tool for urinary tract infections in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2019 Mar;178(3):363-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30569406?tool=bestpractice.com

A positive nitrite (bacteriuria) or leukocyte esterase (pyuria) result should be followed by a urine culture.[1]European Association of Urology. Guidelines on paediatric urology. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/paediatric-urology/chapter/introduction

[4]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary tract infection in under 16s: diagnosis and management. Jul 2022 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng224

The American Society of Microbiology and the Infectious Diseases Society of America do not recommend ordering urine cultures unless patients have clinical signs of UTI because routine culture of asymptomatic individuals may detect asymptomatic bacteriuria.[50]American Society for Microbiology. Five things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely, an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. 2021 [internet publication].

https://web.archive.org/web/20230320213810/https://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/the-american-society-for-microbiology

[51]Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e83-e110.

https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/68/10/e83/5407612

However, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends urine culture in the following scenarios:[4]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary tract infection in under 16s: diagnosis and management. Jul 2022 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng224

The child is <3 months old

There is suspicion of upper UTI

There is an intermediate to high risk of serious illness

The child has a positive result for leukocyte esterase or nitrite

The UTI is recurrent

The UTI does not respond to treatment within 24-48 hours

The child has signs and symptoms, but the dipstick test results are negative.

Urine culture

Samples for culture should be obtained by clean-catch, suprapubic aspiration, or catheterization. Do not perform a bagged urine specimen for urine culture because there is a high false-positive rate.[1]European Association of Urology. Guidelines on paediatric urology. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/paediatric-urology/chapter/introduction

[52]American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Urology. Five things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely, an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. 2022 [internet publication].

https://web.archive.org/web/20230325231547/https://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/aap-pediatric-urology

However, bag urine specimens can be used for urinalysis. If urinalysis is negative, a UTI is unlikely. If positive, an appropriate specimen should be obtained for culture.[1]European Association of Urology. Guidelines on paediatric urology. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/paediatric-urology/chapter/introduction

The following concentrations generally indicate a positive result:[1]European Association of Urology. Guidelines on paediatric urology. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/paediatric-urology/chapter/introduction

[40]Robinson JL, Finlay JC, Lang ME, et al. Urinary tract infections in infants and children: diagnosis and management. Paediatr Child Health. 2014 Jun;19(6):315-25.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4173959

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25332662?tool=bestpractice.com

Suprapubic aspirate: any growth

Clean-catch midstream: >1000-10,000 cfu/mL

Catheterization: >10,000 cfu/mL.

A value of ≥100,000 cfu/mL constitutes severe infection.[1]European Association of Urology. Guidelines on paediatric urology. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/paediatric-urology/chapter/introduction

Preliminary results are usually available after 24 to 48 hours.

Imaging

Imaging is performed to identify structural or functional abnormalities that predispose to recurrent infection, and to detect any complications of infection.

There is divergent clinical opinion as to whether to perform imaging in all children after the first UTI or only in those who are considered to be at highest risk of scarring and underlying abnormalities following UTI. Guideline recommendations differ between world regions.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is readily available and noninvasive. It can identify anatomic abnormalities such as hydronephrosis, duplex renal system, ureterocele, and hydroureter, but has a low sensitivity for detecting vesicoureteral reflux or renal scarring.[11]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: urinary tract infection - child. 2023 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69444/Narrative

Ultrasound may also identify bladder wall trabeculation, increased bladder wall thickness (suggestive or voiding dysfunction or neurogenic bladder), pre- and post-void residual bladder volumes, and rectal diameter (increased in chronic constipation). Ultrasound may be performed to look for evidence of a renal or perinephric abscess when the urinalysis and culture are negative, but abdominal pain and fever persist.

The American College of Radiology (ACR) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommend that all infants under 2 months of age should have a renal ultrasound following their first UTI.[5]Mattoo TK, Shaikh N, Nelson CP. Contemporary management of urinary tract infection in children. Pediatrics. 2021 Feb;147(2):e2020012138.

https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/147/2/e2020012138/36243/Contemporary-Management-of-Urinary-Tract-Infection

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33479164?tool=bestpractice.com

[11]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: urinary tract infection - child. 2023 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69444/Narrative

The AAP and the Canadian Paediatric Society also recommend a renal and bladder ultrasound (RBUS) after the first confirmed febrile UTI for children between 2 and 24 months, and 2 and 36 months of age, respectively.[5]Mattoo TK, Shaikh N, Nelson CP. Contemporary management of urinary tract infection in children. Pediatrics. 2021 Feb;147(2):e2020012138.

https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/147/2/e2020012138/36243/Contemporary-Management-of-Urinary-Tract-Infection

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33479164?tool=bestpractice.com

[40]Robinson JL, Finlay JC, Lang ME, et al. Urinary tract infections in infants and children: diagnosis and management. Paediatr Child Health. 2014 Jun;19(6):315-25.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4173959

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25332662?tool=bestpractice.com

European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines recommend renal and bladder ultrasound within 24 hours in infants with febrile UTI to exclude obstruction of the upper and lower urinary tract.[1]European Association of Urology. Guidelines on paediatric urology. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/paediatric-urology/chapter/introduction

In the UK, NICE recommends ultrasound for infants and children with atypical UTI to identify any structural abnormalities. Infants younger than 6 months with first-time UTI who respond well to treatment should have a non-urgent ultrasound within 6 weeks of diagnosis. Ultrasound is also indicated in those ages 6 months to <3 years in the presence of recurrent UTIs.[4]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary tract infection in under 16s: diagnosis and management. Jul 2022 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng224

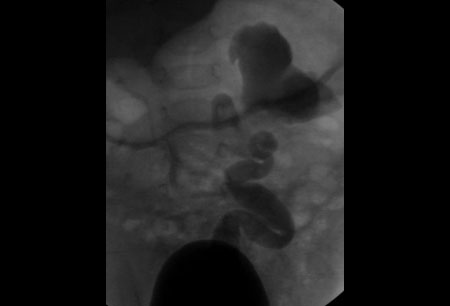

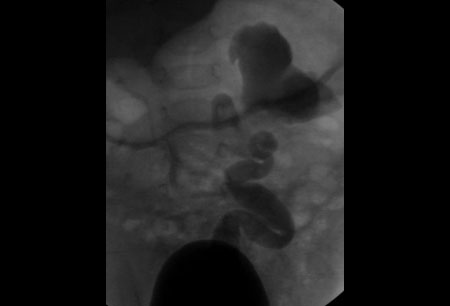

Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG)

VCUG detects vesicoureteral reflux.[11]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: urinary tract infection - child. 2023 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69444/Narrative

VCUG allows evaluation of bladder anatomy (to exclude ureterocele, polyps, and diverticulae) and post-void residual volume. Contrast medium is instilled into the bladder and fluoroscopic images are taken during filling and micturition. A film during voiding permits visualization of the urethra and is essential in male children to exclude posterior urethral valves.[53]Becker A, Baum M. Obstructive uropathy. Early Hum Dev. 2006 Jan;82(1):15-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16377104?tool=bestpractice.com

The AAP recommends that a VCUG is considered in children with abnormal RBUS, atypical causative pathogen, complex clinical course, or known renal scarring.[5]Mattoo TK, Shaikh N, Nelson CP. Contemporary management of urinary tract infection in children. Pediatrics. 2021 Feb;147(2):e2020012138.

https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/147/2/e2020012138/36243/Contemporary-Management-of-Urinary-Tract-Infection

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33479164?tool=bestpractice.com

VCUG may also be considered in patients with a family history of VUR or congenital anomalies of kidneys and the urinary tract after first febrile UTI.[5]Mattoo TK, Shaikh N, Nelson CP. Contemporary management of urinary tract infection in children. Pediatrics. 2021 Feb;147(2):e2020012138.

https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/147/2/e2020012138/36243/Contemporary-Management-of-Urinary-Tract-Infection

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33479164?tool=bestpractice.com

Similarly, the EAU advises that VCUG should only be used if there is a suggestion of high-grade VUR, for example, febrile UTI, abnormal renal ultrasound, and/or non-Escherichia coli infection.[1]European Association of Urology. Guidelines on paediatric urology. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/paediatric-urology/chapter/introduction

NICE recommends VCUG in infants younger than 6 months if they have an abnormal ultrasound, atypical UTI, or recurrent UTI.[4]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary tract infection in under 16s: diagnosis and management. Jul 2022 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng224

A systematic review comparing detection rates of VUR on VCUG found no significant difference between early testing (<8 days after initiation of antibiotics) compared with later testing (≥8 days after initiation of antibiotics).[54]Mazzi S, Rohner K, Hayes W, et al. Timing of voiding cystourethrography after febrile urinary tract infection in children: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2020 Mar;105(3):264-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31466991?tool=bestpractice.com

Neither ultrasound nor renal cortical scintigraphy is sufficiently accurate at detecting VUR to recommend its use for this purpose.[55]Shaikh N, Spingarn RB, Hum SW. Dimercaptosuccinic acid scan or ultrasound in screening for vesicoureteral reflux among children with urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Jul 5;(7):CD010657.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010657.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27378557?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fluoroscopic image showing high-grade vesicoureteral refluxFrom the collection of Dr Mary Anne Jackson [Citation ends].

Renal cortical scintigraphy

Renal cortical scintigraphy uses Tc-99m dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) to detect renal scarring and pyelonephritis.[11]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: urinary tract infection - child. 2023 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69444/Narrative

It is recommended in children with recurrent or atypical UTI by both UK and US guidelines, 4-6 months following the acute infection.[4]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary tract infection in under 16s: diagnosis and management. Jul 2022 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng224

[11]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: urinary tract infection - child. 2023 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69444/Narrative

Further investigations

Serum creatinine, cystatin c, blood urea nitrogen and electrolytes, blood pressure measurements, and urine screening for proteinuria should be performed in patients who are hospitalized with complicated UTI.[1]European Association of Urology. Guidelines on paediatric urology. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/paediatric-urology/chapter/introduction

Inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and procalcitonin) are not recommended routinely. Do not perform procalcitonin testing without an established, evidence-based protocol.[56]American Society for Clinical Pathology. Thirty five things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely, an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. 2022 [internet publication].

https://web.archive.org/web/20230316185857/https://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-society-for-clinical-pathology

Due to heterogeneity between studies, a Cochrane review concluded that there was no compelling evidence to use procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate tests in clinical practice.[57]Shaikh KJ, Osio VA, Leeflang MM, et al. Procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate for the diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Sep 10;(9):CD009185.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009185.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32911567?tool=bestpractice.com

Clinicians may request inflammatory markers and complete blood count to guide decisions about performing lumbar puncture and starting empiric antibiotic therapy in well-appearing infants ≤2 months old.[58]Pantell RH, Roberts KB, Adams WG, et al. Evaluation and management of well-appearing febrile infants 8 to 60 days old. Pediatrics. 2021 Aug;148(2):e2021052228.

https://www.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-052228

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34281996?tool=bestpractice.com

Immunosuppressed patients are susceptible to candidal UTIs. Urine culture for fungus should be specifically requested; this requires different laboratory techniques compared with standard bacterial culture.[59]Achkar JM, Fries BC. Candida infections of the genitourinary tract. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010 Apr;23(2):253-73.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2863365

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20375352?tool=bestpractice.com

Nucleic acid amplification testing for chlamydial infection and gonorrhea is recommended in sexually active adolescents. See Genital tract chlamydia infection and Gonorrhea infection for more information.

Possible infection with schistosomiasis should also be considered, especially with a recent or past history of travel to a tropical country. See Schistosomiasis for more information.