Approach

Suspect retinal detachment (RD) in any patient with a sudden disturbance in their visual field and/or loss of central vision. Presenting complaints of flashes of light or sudden "floaters" suggest a retinal break or detachment. Sudden disturbance in the visual field and/or loss of central vision may suggest a major vitreous hemorrhage. Prompt referral to an ophthalmologist is recommended for patients presenting with serious ocular symptoms or signs.[37][38]

In most cases, the patient with a rhegmatogenous RD presents with sudden-onset visual symptoms (i.e., loss of vision) severe enough to seek evaluation. In a few cases, RD may be discovered incidentally during a routine fundus exam or by the patient when he or she covers the good eye.

Nonrhegmatogenous RDs can develop very slowly (tractional), rather rapidly (exudative), or instantaneously (hemorrhagic). Flashes of light signifying acute retinal traction are much rarer in nonrhegmatogenous RDs because of the condition’s slow progression.

History

Symptomatic patients typically present with a sudden and marked deterioration of central vision, or less often, with loss of peripheral visual fields. Preceding symptoms, such as flashes of light or the sudden appearance of visual "floaters," may only be elicited on direct questioning. Although floaters indicate vitreous opacity, often due to aging, certain presentations may suggest retinal pathology. For example, the sudden onset of a large central floater suggests the presence of a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) and an operculum, whereas numerous small floaters suggest retinal hemorrhage.[39]

Take a full ophthalmic history. Ascertain any history of trauma, refractive errors, or eye surgery. A high index of suspicion is required in a patient with a history of symptomatic PVD or rhegmatogenous RD in the fellow eye.

Rhegmatogenous RD may result from retinal necrosis (e.g., after herpes zoster or herpes simplex infection) or a secondary scarring process (e.g., Toxocara infection).[28][29] For eyes with nonrhegmatogenous RD, risk factors include diabetes mellitus, intraocular tumor, and age-related macular degeneration. Exudative RD may be due to an inflammatory process in the vitreous, retina, uvea, or posterior sclera (e.g., Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome).[2] Other causes include vascular anomalies (e.g., Coats disease) and central serous chorioretinopathy.

Ophthalmic evaluation

The evaluation of all patients should include visual acuity plus examination of the vitreous and retina by slit-lamp and an indirect ophthalmoscopy. The fellow eye in a patient with nontraumatic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) is at increased risk of developing RRD.[17] Both the affected eye and the fellow eye should be evaluated, so that risk factors for subsequent RD in the fellow eye may be determined.

Scleral indentation during ophthalmoscopy allows dynamic evaluation and examination of the anterior retina and may uncover retinal flaps in relief at the apex of the indent.

Presentation may be delayed in children, especially in nontraumatic cases, who may have worse visual acuity, bilateral RD, macula-off RD, PVR, and strabismus at examination.[19] Strabismus may indicate a chronic RD. Use age-appropriate methods for pediatric vision screening.[27]

Rhegmatogenous RD

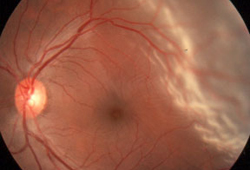

Presents with RD, retinal breaks, and vitreoretinal pathology (traction or pigment). In the absence of a formal staging system, describe the quadrants involved, together with how many and whether the macula is also detached (i.e., macula on and macula off)

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Retinal detachment approaching the macula, showing typical, full-thickness foldsFrom the collection of Dr F. Kuhn and Dr R. Morris, with permission [Citation ends].

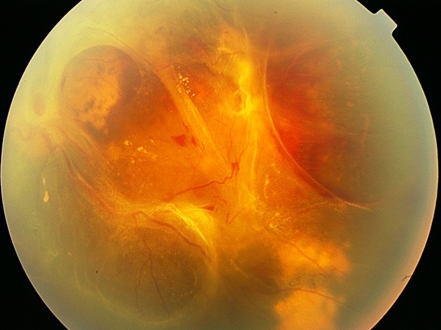

Tractional RD

Often presents with a concave, not convex, retina with markedly less mobility than with rhegmatogenous RD. No break is found, but preretinal and/or subretinal membranes are often seen.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Tractional retinal detachment in a patient with diabetesFrom the collection of Dr F. Kuhn and Dr R. Morris, with permission [Citation ends].

Combined rhegmatogenous/tractional RD

The ractional element usually dominates, but retinal breaks may also be found.

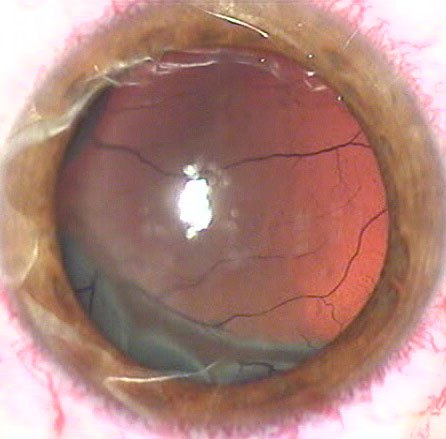

Exudative RD

The subretinal fluid shifts with movement of the patient's head, with a tendency to accumulate inferiorly. The retinal surface appears smooth, with no folds or irregularities. If chronic, hard exudative deposits may appear subretinally. During ophthalmoscopy, reposition the patient's head to observe any shift in the subretinal fluid.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Uveitis-related serous retinal detachmentFrom the collection of Dr F. Kuhn and Dr R. Morris, with permission [Citation ends].

Hemorrhagic RD

Blood in the subretinal space is readily identified by its dark color and the absence of a fluid shift. With time, the color becomes yellowish.

Imaging

Rarely needed, except in the presence of vitreous hemorrhage, other media opacity, or a recent history of trauma.

Wide-field color photography: can detect peripheral breaks if the patient does not tolerate careful ophthalmoscopy.

Optical coherence tomography: can detect the four stages of PVD (i.e., perifoveal separation and vitreous adhesion to the fovea; complete separation of the vitreous and macula; extensive vitreous separation with adherence to the disc; and complete PVD).[40]

B-scan ultrasonography of the affected eye: ordered when any media opacity prevents visualization of the fundus.[17][41] Under standard ultrasonography, direct the patient to move their eye to provide a dynamic understanding of the vitreoretinal architecture. False-positives may occur, with one study showing that B-scan ultrasonography falsely identified the presence of RD behind a vitreous hemorrhage in 19% of eyes.[42] Although ultrasound can aid in the differential diagnosis, it offers less value than direct visualization.

Orbital CT or MRI: consider if recent injury has occurred or is suspected. A breach in the eye wall or the presence of an intraocular foreign body raises the likelihood of a concurrent or rhegmatogenous RD. Intraorbital foreign bodies can also cause retinal necrosis without breaching the eye wall and can lead to a rhegmatogenous RD.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer