Approach

The signs and symptoms of bacterial meningitis depend on the patient's age. In children particularly, early signs and symptoms of meningitis can be nonspecific and similar to other common, less serious illnesses. Even when a diagnosis of bacterial meningitis appears unlikely at the time of presentation, information provided to patients, parents, or caregivers should include:

A specific instruction to seek further advice if warning symptoms develop or the patient's condition deteriorates

An indication of when and how to access further care ("safety netting").[37]

It may be impossible to differentiate between viral and bacterial meningitis clinically. The diagnosis is confirmed by examination and polymerase chain reaction (PCR), culture of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) obtained from a lumbar puncture (LP), or blood culture (if an LP is not clinically safe to obtain).

History

Classic symptoms of meningitis in children and adults include fever, severe headache, neck stiffness, photophobia, altered mental status, vomiting, and seizures.[1][9] The classic triad of fever, neck stiffness, and altered mental status occurs in only 41% to 51% of patients.[38] However, in one study, 95% had at least two of the four symptoms of headache, fever, neck stiffness, and altered mental status.[27] Children have seizures more frequently when infected with Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) than with meningococcal meningitis.[1]

Atypical clinical manifestations tend to occur in very young, older, or immunocompromised patients. In infants the signs and symptoms can be nonspecific and may include fever, hypothermia, irritability, high-pitched crying, lethargy, poor feeding, seizures, apnea, or a bulging fontanel.[39] Frequently, in older patients (>65 years) the only presenting sign of meningitis is confusion or an altered mental status.[1] Focal neurologic deficits, including aphasia, hemiparesis, or cranial nerve palsies, may be present in adults with community-acquired bacterial meningitis.[40]

A careful history to rule out possible viral infections, such as enteroviruses (e.g., other sick children or family members) or herpes virus infection (e.g., sore on lip or genital lesions), should be taken. Immunization history against H influenzae type b, S pneumoniae, and Neisseria meningitidis should be established.

Examination

After assessment of vital signs and mental status, the following should be evaluated:

Nuchal rigidity

A stiff neck with resistance to passive neck flexion is a classic sign of meningitis. It is present in 83% of adults, but may be present in only 30% of children.[27][38][41]

Rash

A petechial or purpuric rash is typically associated with meningococcal meningitis but can also occur in pneumococcal meningitis.[27]

Although only a few patients with fever and a petechial rash will ultimately be found to have meningococcal infections, these findings should prompt investigations to exclude meningococcemia and to start empiric antibacterial therapy unless an alternative diagnosis is likely.

Papilledema, bulging fontanel in infants

The presence of these indicates raised intracranial pressure.

Evidence of primary source of infection

The patient may also have sinusitis, pneumonia, mastoiditis, or otitis media.

Cranial nerve palsy (III, IV, VI)

This is suggested by problems with eye movement and is probably related to increased intracranial pressure.

Cranial nerves VII and VIII may also be involved and damaged due to increased intracranial pressure and inflammation. This damage may lead to facial palsy, balance problems, and hearing impairment.

Kernig and Brudzinski signs

Positive signs are indicators of meningitis commonly in older children and adults, but they may be absent in up to 50% of adults.[1]

Kernig sign: with the patient supine and the thigh flexed to a 90° right angle, attempts to straighten or extend the leg are met with resistance.

Brudzinski signs: flexion of the neck causes involuntary flexion of the knees and hips, or passive flexion of the leg on one side causes contralateral flexion of the opposite leg.

Investigations

LP and analysis of CSF

An LP to obtain CSF is the most important investigation (gold standard) when a diagnosis of bacterial meningitis is suspected. At least 15 mL of CSF is required for investigations.[42] In bacterial meningitis the CSF pressure is usually elevated (>20 cm H₂O).

The CSF white blood cell count is elevated (usually >1000 cells/microliter), of which over 90% are polymorphonuclear leukocytes. In neonates, however, the CSF leukocyte count may be normal.[43]

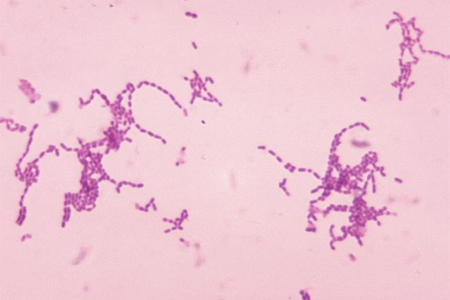

The glucose level in the CSF is decreased compared with the serum value, and the protein level is increased, indicating accelerated bacterial growth. In untreated patients, Gram stain and bacterial culture of the CSF are usually positive for the causative organism. Bacterial culture of CSF is positive in 80% of cases.[27] However, diagnostic yields can be much lower in patients who have received antibiotics before cultures are obtained. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Photomicrograph of Gram-stained Streptococcus species bacteriaImage provided by the CDC Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

Diagnostic lumbar puncture in adults: animated demonstration

Diagnostic lumbar puncture in adults: animated demonstrationHow to perform a diagnostic lumbar puncture in adults. Includes a discussion of patient positioning, choice of needle, and measurement of opening and closing pressure.

Serogroup A, B, C, Y, and W-135 polysaccharide antigen can be detected by latex agglutination in 22% to 93% of patients with meningococcal meningitis.[4] Antigen may persist in the CSF for several days, making this test useful in patients treated with antibiotics before diagnostic specimens could be obtained, and for the rapid presumptive diagnosis of meningococcal infection. Serogroup B N meningitidis and serotype K1 Escherichia coli polysaccharides cross-react, so test results should be interpreted cautiously in neonates. Antigen detection testing on body fluids other than CSF, including serum or urine, is not recommended because of poor sensitivity and specificity.

A cranial computed tomography (CT) scan should be considered before LP in the presence of focal neurologic deficit, new-onset seizures, papilledema, abnormal level of consciousness, or immunocompromised state to exclude a brain abscess or generalized cerebral edema.[38]

PCR

PCR amplification of bacterial DNA from blood and CSF is more sensitive and specific than traditional microbiologic techniques. It is especially useful in distinguishing bacterial from viral meningitis; false-negative results are uncommon (about 5% of cases).[4] It is also helpful in diagnosing bacterial meningitis in patients who have been pretreated with antibiotics.[50]

Real-time PCR assay can identify specific serogroup (N meningitidis) or serotype (H influenzae) from clinical isolates (typically blood or CSF).[51]

Blood analysis

Baseline blood tests: include complete blood count, electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, phosphate, and coagulation profile.

Blood culture: performed in all patients, ideally before giving antibiotics. However, taking blood for culture should not delay administration of antibiotics. As with CSF culture, the result may be influenced by previous antimicrobial therapy. For example, in one retrospective review blood cultures were positive in approximately 50% of untreated patients with meningococcal disease, but only 5% of patients who received an antibiotic before admission.[52]

Serum C-reactive protein (CRP): this value tends to be elevated in patients with bacterial meningitis. In patients where the CSF Gram stain is negative and the differential diagnosis is between bacterial and viral meningitis, a normal serum CRP concentration excludes bacterial meningitis with approximately 99% certainty.[53][54]

Serum procalcitonin: this has both sensitivity and specificity of over 90% when used to distinguish between bacterial and viral meningitis.[55][56][57] Do not perform procalcitonin testing without an established, evidence-based protocol.[58]

Imaging

A cranial CT scan should be considered before LP in the presence of focal neurologic deficit, new-onset seizures, papilledema, abnormal level of consciousness, or immunocompromised state to exclude a brain abscess or generalized cerebral edema.[38]

Cranial imaging with magnetic resonance imaging may be used to identify underlying conditions and meningitis-associated complications. Brain infarction, cerebral edema, and hydrocephalus are common findings especially in pneumococcal meningitis.[59] Should be used if there are focal neurologic signs.

How to take a venous blood sample from the antecubital fossa using a vacuum needle.

How to perform a diagnostic lumbar puncture in adults. Includes a discussion of patient positioning, choice of needle, and measurement of opening and closing pressure.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer