Approach

A strong index of suspicion must underlie investigation for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). There are no diagnostic criteria for APS. However, classification criteria (originally formulated for research purposes in Sapporo, Japan, and subsequently updated by ACR/EULAR) are often used as a guide for APS diagnosis.[1][2][3] These classification criteria are based on clinical criteria, including thrombosis and/or pregnancy morbidity, and laboratory factors that include persistently positive APS antibody tests.[1][2] The ACR/EULAR criteria are considered more specific for APS, meaning a patient has a high likelihood of APS if the criteria are met. The Sapporo criteria are more sensitive, meaning they are less likely to miss patients with APS. Patients meeting the Sapporo criteria but not the ACE/EULAR criteria may still have APS and clinical judgment should be used to determine best management strategy.[29]

Those with at least one positive antiphospholipid antibody (aPL) test within 3 years of an aPL-associated clinical criterion can be classified with the ACR/EULAR criteria.[2]

There are six clinical domains (macrovascular venous thromboembolism, macrovascular arterial thrombosis, microvascular, obstetric, cardiac valve, and hematologic) and two laboratory domains (aPL tests by coagulation assay and solid-phase assay) in the ACR/EULAR classification.[2]

Items in each of the eight domains receive a score between 1 and 7. People who score at least 3 points in both the clinical and the laboratory domains are classified as having APS.[2]

In the ACR/EULAR criteria, venous or arterial thrombosis occurring as a result of known risks and provoking factors are scored lower. If strong or multiple risk factors are present, testing for APS is discouraged.

Patients with IgM antibodies are scored lower and, in isolation, would not meet laboratory scoring threshold for APS diagnosis in the new ACR/EULAR criteria. Controversy exists on the thrombotic risk of these patients, with a recognized need for more research to determine appropriate management.

History and examination

Key factors in the history that support the diagnosis include the following.[1][2]

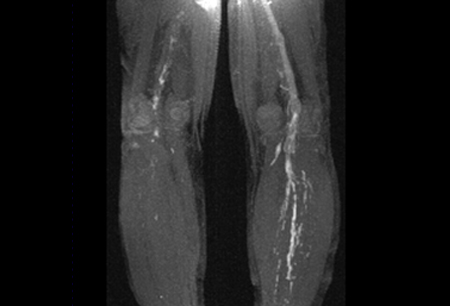

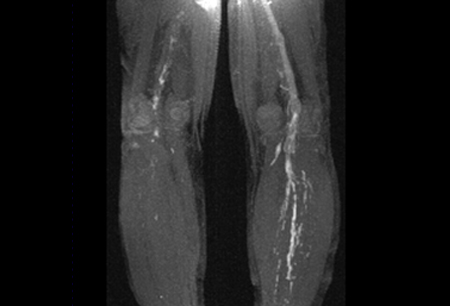

A documented thrombotic event (venous, arterial, or microvascular). [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging of bilateral proximal DVTFrom the personal teaching collection of Professor Hunt; used with permission [Citation ends].

A history of recurrent pregnancy loss <10 weeks' gestation or pregnancy loss between 10th week of gestation and the 34th week of gestation or pregnancy-related complications (eclampsia, severe preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, or placental insufficiency) resulting in premature birth of a morphologically normal neonate before the 34th week of gestation.

Apparently spontaneous venous thromboembolic events and young patients (<50 years) presenting with stroke, coronary artery thrombus, or peripheral arterial events should prompt testing for APS antibodies.

A thrombotic myocardial infarction: those with this presentation should be assumed to have APS until confirmed otherwise.

Heart valve abnormalities such as otherwise unexplained valve thickening or the presence of vegetations.

A history of hematologic abnormalities such as otherwise unexplained thrombocytopenia or hemolytic anemia.

APS occurring in conjunction with an underlying rheumatic or connective tissue disorder was previously known as secondary APS. A history of lupus or a lupus-like syndrome is a risk factor for APS but is not a clinical diagnostic criterion. Other manifestations of the disease include rheumatologic or autoimmune disorders, such as Sjogren syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. Several clinical manifestations associated with APS are not included in the specific classification criteria and include livedo reticularis, skin rash (which is often nonspecific), vasculitis, nephropathy, edema, proteinuria, and pulmonary hemorrhage.[4][30][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Livedo reticularisFrom the personal teaching collection of Professor Hunt; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Livedo reticularisFrom the personal teaching collection of Professor Hunt; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Livedo reticularisFrom the personal teaching collection of Professor Hunt; used with permission [Citation ends].

Rarely nephropathy (manifesting as edema and proteinuria) can be due to microangiopathic thrombosis secondary to APS.[31] Neurologic manifestations include seizure, headache, memory loss, and transverse myelopathy.[32][33] Patients may also present with arthralgia or arthritis. Attention should also be paid to signs of postphlebitic syndrome, such as leg swelling, varicose veins, skin discoloration, and ulceration.[34]

Laboratory investigation

Screening for antiphospholipid antibodies should be performed if there is a clinical suspicion of APS. Laboratory confirmation of the presence of aPL on 2 occasions at least 12 weeks apart is required for the diagnosis.[35] aPL antibodies include the following: lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, and anti-beta2-glycoprotein I antibody (anti-B2GP-I antibody).[2] The presence of aPL may be transient due to infection, lymphoproliferative disorders, and drug exposures. In a significant proportion of patients, aPL detection is an incidental finding in apparently otherwise healthy patients, and risk of thrombosis in these patients is relatively low. For this reason, APS is confirmed after 2 tests, 12 weeks apart.

Diagnosis of lupus anticoagulants is based on coagulation assays and involves an initial detection stage, followed by a confirmation stage.[36][37] The principle of the assay is the prolongation of a phospholipid-dependent coagulation test by the antibody. In the confirmation stage, addition of negatively charged phospholipid binds the antibody and thus the coagulation time is shortened. Whenever possible, lupus anticoagulant testing should be performed before initiation of anticoagulation as anticoagulants may lead to false-positive results. When this is not possible, testing can be performed on unfractionated heparin or low molecular heparin as long as the assay contains a heparin neutralizer and drug levels are not supratherapeutic.[38] Testing for lupus anticoagulants in patients on direct oral anticoagulants is not recommended unless they are removed or neutralized. Anticardiolipin antibodies and anti-B2GP-I antibodies are detected by solid-phase immunoassay (standardized enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) and are not affected by anticoagulation. Anticardiolipin antibodies should be of immunoglobulin (Ig) G and/or IgM isotype in serum or plasma, present in medium or high titer (i.e., >40 IgG phospholipid [GPL] units or IgM phospholipid [MPL] units or >99th percentile).[1][2][39] Anti-B2GP-I antibody should be of IgG and/or IgM isotype in serum or plasma (in titer >99th percentile).[2]

It must be emphasized that only about one third of patients with APS have a lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, and anti-beta2-glycoprotein I antibodies (i.e., they are triple-positive). Many patients may be positive for only a lupus anticoagulant or anticardiolipin antibody alone. Thus, an appropriate initial work up for APS must include all of the laboratory tests.

Other laboratory investigations should include the following: complete blood count to rule out thrombocytopenia and anemia, creatinine and blood urea nitrogen for renal function, and screening for autoimmune disorders if clinically suspected. In patients presenting with venous thromboembolism at an early age and with a family history of thrombosis, an inherited thrombophilia test measuring levels of protein C, protein S, antithrombin, and factor V Leiden and/or polymerase chain reaction for prothrombin gene mutation (G-20210-A) should be considered to exclude an underlying inherited thrombophilia.

In patients found to have antiphospholipid antibodies, or with a history of pregnancy-related morbidity (obstetric APS), testing for additional thrombophilic disorders should be done only if there is a high index of suspicion for an inherited thrombophilia, such as a family history of venous thromboembolism.

Imaging

In patients presenting with clinical features suggesting a venous or arterial thromboembolic event, appropriate radiologic investigations should be performed. Venous Doppler or venography computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be done to confirm a deep vein thrombosis. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging of bilateral proximal DVTFrom the personal teaching collection of Professor Hunt; used with permission [Citation ends]. Computed tomography angiogram of the chest or ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scan is required for confirmation in those suspected of having a pulmonary embolus. Cranial imaging with MRI is required for patients presenting with stroke. Echocardiography is indicated in patients with clinical features indicative of heart valve lesions or vegetations (i.e., unexplained arterial thromboembolism or heart murmur). A transesophageal echocardiogram is the most sensitive study to identify these lesions and should be performed if there is a high index of suspicion.

Computed tomography angiogram of the chest or ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scan is required for confirmation in those suspected of having a pulmonary embolus. Cranial imaging with MRI is required for patients presenting with stroke. Echocardiography is indicated in patients with clinical features indicative of heart valve lesions or vegetations (i.e., unexplained arterial thromboembolism or heart murmur). A transesophageal echocardiogram is the most sensitive study to identify these lesions and should be performed if there is a high index of suspicion.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer