Aortic dissection should be suspected when an abrupt onset of tearing or ripping chest, back or abdominal pain is reported.[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

[11]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-e454.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients typically describe the pain as severe “sharp” or “stabbing”, maximal at onset.[4]Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36334952?tool=bestpractice.com

Missing the diagnosis may be catastrophic, hence the importance of acute history taking to prompt further investigation.[11]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-e454.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

[27]Sutherland A, Escano J, Coon TP. D-dimer as the sole screening test for acute aortic dissection: a review of the literature. Ann Emerg Med. 2008 Oct;52(4):339-43.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18819176?tool=bestpractice.com

The usual presentation is a male patient in their 50s, but the condition may occur in younger patients who have Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, or other connective-tissue disorders.[14]Bossone E, LaBounty TM, Eagle KA. Acute aortic syndromes: diagnosis and management, an update. Eur Heart J. 2018 Mar 1;39(9):739-49d.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx319

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29106452?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36334952?tool=bestpractice.com

Other high-risk scenarios include a family history of aortic disease or connective-tissue disorder, known aortic disease or thoracic aortic aneurysm, and previous aortic manipulation (including cardiac surgery).[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

[11]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-e454.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

Most patients have prior hypertension, often poorly controlled.[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

[11]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-e454.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

Younger patients may have a connective-tissue disorder, or a recent history of heavy lifting or cocaine use. Because of the severity of the condition, the diagnosis should be considered in young patients, even when predisposing factors are absent.

Signs and symptoms

Acute onset of severe chest or back pain heralds acute aortic dissection in 80% to 90% of patients.[11]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-e454.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

The pain associated with aortic dissection may be located retrosternally, interscapularly, or in the lower back.[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Bossone E, LaBounty TM, Eagle KA. Acute aortic syndromes: diagnosis and management, an update. Eur Heart J. 2018 Mar 1;39(9):739-49d.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx319

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29106452?tool=bestpractice.com

Although the classic textbook description is of acute “tearing” or “ripping” pain, patients more commonly report the abrupt onset of severe “sharp” or “stabbing” pain, maximal at onset.[4]Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36334952?tool=bestpractice.com

Anterior chest pain is typically associated with an ascending dissection; interscapular pain usually occurs with a descending dissection.[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Bossone E, LaBounty TM, Eagle KA. Acute aortic syndromes: diagnosis and management, an update. Eur Heart J. 2018 Mar 1;39(9):739-49d.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx319

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29106452?tool=bestpractice.com

Pain may migrate through the thorax or abdomen, and the location of pain may change with time as the dissection extends.[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Bossone E, LaBounty TM, Eagle KA. Acute aortic syndromes: diagnosis and management, an update. Eur Heart J. 2018 Mar 1;39(9):739-49d.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx319

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29106452?tool=bestpractice.com

A minority of patients present with syncope and no pain.[11]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-e454.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

It is important to recognize that no single symptom of aortic dissection is pathognomonic for the condition, as there is overlap with cardiac, pulmonary, abdominal, and musculoskeletal disorders.

Patients may be hemodynamically stable or in hypovolemic shock.[4]Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36334952?tool=bestpractice.com

Blood pressure differences in the upper extremities or pulse deficits in the lower extremities should be sought.[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36334952?tool=bestpractice.com

A pulse deficit is particularly common in a proximal dissection affecting the aortic arch.[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

[11]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-e454.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

The deficit may be unilateral or bilateral depending on the level of the intimal flap.[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

A pulse deficit may also be present in more distal aortic dissections (e.g., of the descending aorta) and, in some cases, may lead to acute limb ischemia. However, pulse deficits are less common than in more proximal dissections.[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

A difference in systolic blood pressure of greater than 20 mmHg between the two arms is a key sign of aortic dissection.[4]Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36334952?tool=bestpractice.com

Neurologic deficits may indicate involvement of cerebral or intercostal vessels. There may be depressed mental status, limb pain, paresthesia, weakness, or paraplegia. Symptoms of visceral ischemia may be present. Occasionally, a diastolic decrescendo murmur may be discovered, indicating aortic insufficiency. There may be symptoms or signs of heart failure, pericardial tamponade, or a left pleural effusion.[11]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-e454.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

See Pleural effusion.

One systematic review identified neurologic deficit, hypotension, and a pulse deficit as the three clinical examination findings with the highest positive likelihood ratios for aortic dissection.[28]Ohle R, Kareemi HK, Wells G, et al. Clinical examination for acute aortic dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2018 Apr;25(4):397-412.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/acem.13360

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29265487?tool=bestpractice.com

Tests

The choice of investigations for diagnostic work-up of acute dissection is based on the patient’s hemodynamic status, likelihood of aortic dissection, and local availability and expertise.[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36334952?tool=bestpractice.com

Initial work-up includes ECG, and cardiac enzymes to exclude myocardial infarction.[4]Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36334952?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Bossone E, LaBounty TM, Eagle KA. Acute aortic syndromes: diagnosis and management, an update. Eur Heart J. 2018 Mar 1;39(9):739-49d.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx319

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29106452?tool=bestpractice.com

See ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Myocardial ischemia or infarction may be present in 10% to 15% of patients with aortic dissection, which can mask the diagnosis of dissection.[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

Blood tests including a complete metabolic panel and complete blood count, including blood type and crossmatch, should also be requested. Despite a high sensitivity, D-dimer is not recommended as the sole screening tool for acute aortic dissection; while negative D-dimer may be helpful to rule out aortic dissection in low-risk patients, particularly when used within an integrated decision support tool, a positive D-dimer lacks specificity when used in isolation.[29]Asha SE, Miers JW. A systematic review and meta-analysis of D-dimer as a rule-out test for suspected acute aortic dissection. Ann Emerg Med. 2015 Oct;66(4):368-78.

http://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(15)00118-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25805111?tool=bestpractice.com

[30]Baez AA, Cochon L. Improved rule-out diagnostic gain with a combined aortic dissection detection risk score and D-dimer Bayesian decision support scheme. J Crit Care. 2017 Feb;37:56-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27632799?tool=bestpractice.com

However, D-dimer will be of value when considering the differential diagnosis (e.g., pulmonary embolus).[27]Sutherland A, Escano J, Coon TP. D-dimer as the sole screening test for acute aortic dissection: a review of the literature. Ann Emerg Med. 2008 Oct;52(4):339-43.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18819176?tool=bestpractice.com

Other biomarkers with the potential to assist in the diagnosis of aortic dissection include C-reactive protein, elastin degradation products, calponin, and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, but none of these have been validated.[31]Ranasinghe AM, Bonser RS. Biomarkers in acute aortic dissection and other aortic syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 Nov 2;56(19):1535-41.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21029872?tool=bestpractice.com

In patients with a suspected aortic dissection, computed tomography angiography (CTA) is recommended for initial diagnostic imaging, given its wide availability, accuracy, and speed, as well as the extent of anatomic detail it provides.[4]Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36334952?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Fleischmann D, Afifi RO, Casanegra AI, et al. Imaging and surveillance of chronic aortic dissection: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022 Mar;15(3):e000075.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/HCI.0000000000000075

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35172599?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

[11]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-e454.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Bossone E, LaBounty TM, Eagle KA. Acute aortic syndromes: diagnosis and management, an update. Eur Heart J. 2018 Mar 1;39(9):739-49d.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx319

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29106452?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Expert Panel on Cardiac Imaging., Kicska GA, Hurwitz Koweek LM, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Suspected acute aortic syndrome. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 Nov;18(11s):S474-S481.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2021.09.004

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34794601?tool=bestpractice.com

[33]Upchurch GR Jr, Escobar GA, Azizzadeh A, et al. Society for Vascular Surgery clinical practice guidelines of thoracic endovascular aortic repair for descending thoracic aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2021 Jan;73(1s):55S-83S.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2020.05.076

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32628988?tool=bestpractice.com

[34]Czerny M, Schmidli J, Adler S, et al. Editor's Choice - current options and recommendations for the treatment of thoracic aortic pathologies involving the aortic arch: an expert consensus document of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) & the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2019 Feb;57(2):165-98.

https://www.ejves.com/article/S1078-5884(18)30692-0/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30318395?tool=bestpractice.com

CTA has a sensitivity greater than 90% and specificity greater than 85% for acute aortic syndromes, including aortic dissection.[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

CTA also shows the full extent of the dissection and, in some cases, the entry tear site. CTA can detect the presence and mechanism of aortic branch vessel involvement as well as vessel patency, signs of malperfusion, pericardial effusion and hemopericardium, periaortic or mediastinal hematoma, and pleural effusion.[4]Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36334952?tool=bestpractice.com

For patients who cannot receive iodinated contrast, CT without contrast is an acceptable alternative.

The diagnosis of aortic dissection is made by imaging an intimal flap separating 2 lumens. If the false lumen is completely thrombosed, central displacement of the intimal flap, calcification, or separation of intimal layers are definitive signs of aortic dissection. CTA also allows visualization of the extent of dissection and involvement of side branches.

A plain chest x-ray is neither sufficiently sensitive nor specific for aortic dissection to be used as a diagnostic tool. A chest x-ray may reveal other causes of acute chest pain.[4]Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36334952?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Expert Panel on Cardiac Imaging., Kicska GA, Hurwitz Koweek LM, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Suspected acute aortic syndrome. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 Nov;18(11s):S474-S481.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2021.09.004

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34794601?tool=bestpractice.com

[33]Upchurch GR Jr, Escobar GA, Azizzadeh A, et al. Society for Vascular Surgery clinical practice guidelines of thoracic endovascular aortic repair for descending thoracic aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2021 Jan;73(1s):55S-83S.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2020.05.076

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32628988?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36334952?tool=bestpractice.com

Widening of the mediastinum or pleural effusion can indicate aortic dissection but is of limited diagnostic value, particularly if the dissection is confined to the ascending aorta; chest x-ray is normal in up to 40% of patients with aortic dissection.[11]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-e454.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Bossone E, LaBounty TM, Eagle KA. Acute aortic syndromes: diagnosis and management, an update. Eur Heart J. 2018 Mar 1;39(9):739-49d.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx319

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29106452?tool=bestpractice.com

[34]Czerny M, Schmidli J, Adler S, et al. Editor's Choice - current options and recommendations for the treatment of thoracic aortic pathologies involving the aortic arch: an expert consensus document of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) & the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2019 Feb;57(2):165-98.

https://www.ejves.com/article/S1078-5884(18)30692-0/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30318395?tool=bestpractice.com

[35]von Kodolitsch Y, Nienaber CA, Dieckmann C, et al. Chest radiography for the diagnosis of acute aortic syndrome. Am J Med. 2004 Jan 15;116(2):73-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14715319?tool=bestpractice.com

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) may be used in the emergency department, intensive care unit (ICU), or operating room for acute proximal dissections if the patient is clinically unstable and there is any question about the diagnosis, or if CTA is unavailable or contraindicated.[11]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-e454.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Expert Panel on Cardiac Imaging., Kicska GA, Hurwitz Koweek LM, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Suspected acute aortic syndrome. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 Nov;18(11s):S474-S481.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2021.09.004

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34794601?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Nazerian P, Vanni S, Morello F, et al. Diagnostic performance of focused cardiac ultrasound

performed by emergency physicians for the assessment of ascending aorta dilation and aneurysm. Acad Emerg Med. 2015 May;22(5):536-41.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25899650?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36334952?tool=bestpractice.com

TTE can show pericardial effusion or aortic regurgitation, and a dissection flap can sometimes be visualized; however, more complete imaging of the aortic arch requires transesophageal echocardiography or CTA.[4]Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36334952?tool=bestpractice.com

For type A dissections (ascending), transesophageal echocardiography may be done in the ICU or operating room to confirm the diagnosis and better evaluate the aortic valve.[11]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-e454.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

Sensitivity and specificity are higher than for TTE.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is most often used as a follow-up imaging modality in patients in which there is diagnostic uncertainty.[4]Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec 13;80(24):e223-e393.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36334952?tool=bestpractice.com

Magnetic resonance angiography is the most accurate, sensitive, and specific test for aortic dissection, but is rarely used in the acute setting because it is more difficult to obtain than CTA.[2]Lombardi JV, Hughes GC, Appoo JJ, et al. Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) and Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) reporting standards for type B aortic dissections. J Vasc Surg. 2020 Mar;71(3):723-47.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2019.11.013

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32001058?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

In the setting of type B dissections (descending), if medical therapy fails and surgery is required, intraoperative intravascular ultrasound helps define the morphology of the dissection and assists in the treatment plan.

If the patient presents with an incidental finding of chronic dissection (such as mediastinal widening or prominent aortic knob on chest x-ray), diagnosis is confirmed by cross-sectional imaging such as CTA, TTE, or MRI.[24]Fleischmann D, Afifi RO, Casanegra AI, et al. Imaging and surveillance of chronic aortic dissection: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022 Mar;15(3):e000075.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/HCI.0000000000000075

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35172599?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/35/41/2873/407693/2014-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25173340?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Transesophageal echocardiography (transverse aortic section) showing a circumferential dissection of the ascending aorta in a 30-year-old patient with features of Marfan syndromeBouzas-Mosquera A, Solla-Buceta M, Fojón-Polanco S. Circumferential aortic dissection. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2007.049908 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing dissecting aneurysm in a 45-year-old patient with Marfan syndrome experiencing chest painSanyal K, Sabanathan K. Chest pain in Marfan syndrome. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2008.0431 [Citation ends].

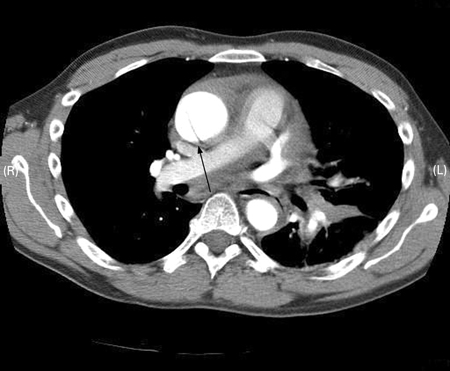

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing dissecting aneurysm in a 45-year-old patient with Marfan syndrome experiencing chest painSanyal K, Sabanathan K. Chest pain in Marfan syndrome. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2008.0431 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: 3D CT, distal dissectionFrom the collection of Dr Eric E. Roselli; used with permission [Citation ends].

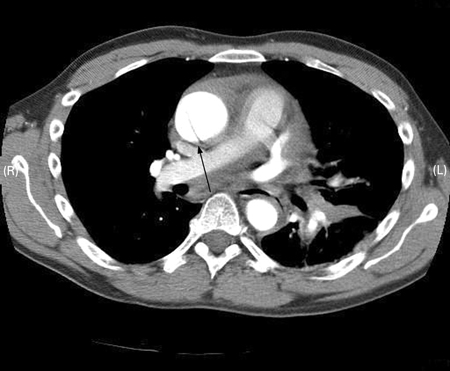

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: 3D CT, distal dissectionFrom the collection of Dr Eric E. Roselli; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT of a 71-year-old man showing type II dissecting aneurysm of the ascending aorta. Hematoma around the proximal segment of the ascending aorta (panels A-D) compressed the right pulmonary artery, almost occluding its patency and limiting the perfusion of the reciprocal lungStougiannos PN, Mytas DZ, Pyrgakis VN. The changing faces of aortic dissection: an unusual presentation mimicking pulmonary embolism. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2006.104414 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT of a 71-year-old man showing type II dissecting aneurysm of the ascending aorta. Hematoma around the proximal segment of the ascending aorta (panels A-D) compressed the right pulmonary artery, almost occluding its patency and limiting the perfusion of the reciprocal lungStougiannos PN, Mytas DZ, Pyrgakis VN. The changing faces of aortic dissection: an unusual presentation mimicking pulmonary embolism. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2006.104414 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing dissecting aneurysm in a 45-year-old patient with Marfan syndrome experiencing chest painSanyal K, Sabanathan K. Chest pain in Marfan syndrome. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2008.0431 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing dissecting aneurysm in a 45-year-old patient with Marfan syndrome experiencing chest painSanyal K, Sabanathan K. Chest pain in Marfan syndrome. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2008.0431 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: 3D CT, distal dissectionFrom the collection of Dr Eric E. Roselli; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: 3D CT, distal dissectionFrom the collection of Dr Eric E. Roselli; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT of a 71-year-old man showing type II dissecting aneurysm of the ascending aorta. Hematoma around the proximal segment of the ascending aorta (panels A-D) compressed the right pulmonary artery, almost occluding its patency and limiting the perfusion of the reciprocal lungStougiannos PN, Mytas DZ, Pyrgakis VN. The changing faces of aortic dissection: an unusual presentation mimicking pulmonary embolism. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2006.104414 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT of a 71-year-old man showing type II dissecting aneurysm of the ascending aorta. Hematoma around the proximal segment of the ascending aorta (panels A-D) compressed the right pulmonary artery, almost occluding its patency and limiting the perfusion of the reciprocal lungStougiannos PN, Mytas DZ, Pyrgakis VN. The changing faces of aortic dissection: an unusual presentation mimicking pulmonary embolism. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2006.104414 [Citation ends].