Management of preeclampsia is based on disease severity and progression.

Mainstays of treatment include:

Monitoring

Deciding on a delivery date and method

Lowering blood pressure (BP)

Controlling seizures

Postpartum fluid management.

The main causes of maternal mortality are stroke and pulmonary edema; therefore, lowering BP and managing postpartum fluid are the most important aspects of treatment, regardless of the presence of other complications such as eclampsia or HELLP syndrome. HELLP syndrome is a subtype of severe preeclampsia characterized by hemolysis (H), elevated liver enzymes (EL), and low platelets (LP). See HELLP syndrome (Management approach).

Management should be in a tertiary-care setting or in consultation with an obstetrician/gynecologist with experience in managing high-risk pregnancies.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

Management differs between countries; however, the basic principles of management are the same.

Hospital admission

Women with clinical findings that warrant close attention should be managed in an inpatient care facility.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

[2]Magee LA, Brown MA, Hall DR, et al. The 2021 International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022 Mar;27:148-69.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35066406?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

On admission, further assessment is required. BP should be monitored regularly for rising levels, need for intervention, and response to therapy; however, there is little guidance on how often this should be performed. A good guide is at least 4 times per day on a floor, or continuously in an intensive care unit.[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

In cases of well-controlled mild to moderate disease, outpatient management can be considered, although close outpatient monitoring in a prenatal day unit or equivalent maternity triage unit, which can facilitate hospital admission, is required.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

[54]Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand. Hypertension in pregnancy guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.somanz.org/hypertension-in-pregnancy-guideline-2023

[Evidence C]785aafe1-a897-4957-9431-ce1eab68794bguidelineCWhat are the effects of outpatient management compared with inpatient management for the treatment of preeclampsia?[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) considers validated risk prediction models such as fullPIERS or PREP-S and now PIGF or sFlt-1/PIGF ratio may be helpful to guide decisions about admission and thresholds for intervention, alongside full clinical assessment.[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

However, by contrast, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not recommend any single biomarker test (e.g., PlGF testing or the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio) for guiding the management approach after a positive or negative test result.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

[60]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Biomarker prediction of preeclampsia with severe features. Obstet Gynecol. 2024 Jun;143(6):p e153-4.

Plan for delivery

The definitive treatment for preeclampsia is delivery; however, this is not always possible immediately. Even after delivery, it may take a few days for the condition to resolve completely.

The decision to deliver can only be made after a thorough assessment of the risks and benefits to both mother and baby. The main risk to the baby is prematurity, a cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality.[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

Neonatal healthcare costs also rise significantly with immediate delivery.[73]van Baaren GJ, Broekhuijsen K, van Pampus MG, et al. An economic analysis of immediate delivery and expectant monitoring in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation (HYPITAT-II). BJOG. 2017 Feb;124(3):453-61.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1471-0528.13957

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26969198?tool=bestpractice.com

If the mother’s condition is considered stable (i.e., absence of seizures, controlled hypertension), a conservative approach is usually taken and the decision to deliver is based on the gestational age.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

[54]Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand. Hypertension in pregnancy guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.somanz.org/hypertension-in-pregnancy-guideline-2023

Early delivery

Early delivery may be indicated if there are concerns about the mother’s condition, such as uncontrolled hypertension, deteriorating blood test results, reduced oxygen saturation, or signs of placental abruption. Delivery may also be warranted for fetal indications, such as abnormal umbilical artery Doppler or cardiotocography concerns.

A rushed delivery for a woman in an unstable condition can be dangerous. Treatment with magnesium sulfate and antihypertensive therapy is necessary before delivery is considered in these women (i.e., presence of seizures, uncontrolled hypertension).[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

Delivery should be considered after the woman’s condition has been stabilized.

The decision and plan for delivery should be discussed with senior obstetric, anesthetic, and neonatal staff.[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

Delivery at <34 weeks' gestation

Prolonging the pregnancy is beneficial for the baby at <34 weeks' gestation, providing fetal assessments are satisfactory. One Cochrane review of expectant management versus delivery between 24 to 34 weeks of gestation found reduced morbidity for the baby for some outcomes.[74]Churchill D, Duley L, Thornton JG, et al. Interventionist versus expectant care for severe pre-eclampsia between 24 and 34 weeks' gestation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Oct 5;(10):CD003106.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003106.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30289565?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

How does interventionist care compare with expectant care for women between 24‐ and 34‐weeks’ gestation who have severe pre‐eclampsia?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.2441/fullShow me the answer Limited data are available regarding the effect of preterm delivery on maternal health.

]

How does interventionist care compare with expectant care for women between 24‐ and 34‐weeks’ gestation who have severe pre‐eclampsia?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.2441/fullShow me the answer Limited data are available regarding the effect of preterm delivery on maternal health.

This approach requires careful in-hospital maternal and fetal surveillance.[75]Publications Committee, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; Sibai BM. Evaluation and management of severe preeclampsia before 34 weeks' gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Sep;205(3):191-8.

https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(11)00918-5/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22071049?tool=bestpractice.com

If delivery is required before 34 weeks' gestation, intravenous magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection of the baby and prenatal corticosteroids to mature fetal lungs are recommended.[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

[76]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 455: magnesium sulfate before anticipated preterm birth for neuroprotection. Mar 2010 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2010/03/magnesium-sulfate-before-anticipated-preterm-birth-for-neuroprotection

If the mother starts to have seizures, that becomes the main target for management, but the baby still gets the benefit.

Delivery at 34 to 36 weeks plus 6 days' gestation

There is limited evidence to guide management, and decisions regarding delivery should be made on a case-by-case basis while monitoring the condition of the mother and baby.

One study of women with nonsevere preeclampsia at 34 to 37 weeks' gestation found that the risk of adverse maternal outcome did not differ between those randomized to immediate delivery or expectant management.[77]Broekhuijsen K, van Baaren GJ, van Pampus MG, et al; HYPITAT-II study group. Immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation (HYPITAT-II): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015 Jun 20;385(9986):2492-501.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25817374?tool=bestpractice.com

However, immediate delivery significantly increased the risk of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome.[77]Broekhuijsen K, van Baaren GJ, van Pampus MG, et al; HYPITAT-II study group. Immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation (HYPITAT-II): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015 Jun 20;385(9986):2492-501.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25817374?tool=bestpractice.com

When the results of this study were combined with those of another randomized trial, earlier planned delivery was associated with a reduction in maternal morbidity and mortality for pregnancies at more than 34 weeks' gestation.[78]Koopmans CM, Bijlenga D, Groen H, et al; HYPITAT Study Group. Induction of labour versus expectant monitoring for gestational hypertension or mild pre-eclampsia after 36 weeks' gestation (HYPITAT): a multicentre, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009 Sep 19;374(9694):979-88.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19656558?tool=bestpractice.com

[79]Cluver C, Novikova N, Koopmans CM, et al. Planned early delivery versus expectant management for hypertensive disorders from 34 weeks gestation to term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 15;(1):CD009273.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009273.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28106904?tool=bestpractice.com

The review authors acknowledged that the data are limited.[79]Cluver C, Novikova N, Koopmans CM, et al. Planned early delivery versus expectant management for hypertensive disorders from 34 weeks gestation to term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 15;(1):CD009273.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009273.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28106904?tool=bestpractice.com

A further study found that early planned delivery for late preterm preeclampsia is better for the mother and does no harm to the baby, although more babies are admitted to the neonatal care unit.[80]Chappell LC, Brocklehurst P, Green ME, et al. Planned early delivery or expectant management for late preterm pre-eclampsia (PHOENIX): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019 Sep 28;394(10204):1181-90.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6892281

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31472930?tool=bestpractice.com

If disease severity in the mother increases, immediate delivery is required. There is likely to be benefit from the administration of prenatal corticosteroids at 34 to 36 weeks, and they should be considered for women who are in suspected, diagnosed, or established preterm labor; are having a planned preterm birth; or have preterm prelabor rupture of membranes.[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

Delivery at >37 weeks' gestation

Delivery is the most sensible approach, and is indicated within 24 to 48 hours.[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

Mode of delivery

The mode of delivery depends on the gestational age, and is determined by individual maternal and fetal factors.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

[54]Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand. Hypertension in pregnancy guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.somanz.org/hypertension-in-pregnancy-guideline-2023

At <32 weeks' gestation, cesarean is the most likely mode of delivery. Attempted vaginal delivery may fail, cause significant fetal morbidity, or be unsafe in a severely ill mother.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

At >32 weeks' gestation the decision should be made on a case-by-case basis, depending on maternal and fetal factors and the mother’s preferences.[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

If a cesarean is performed, regional anesthesia is preferred if tolerated and there is no coagulopathy. If a general anesthetic is used, care should be taken to prevent the hypertensive response to intubation and extubation, and the risk of laryngeal edema.[81]Hein HA. Cardiorespiratory arrest with laryngeal oedema in pregnancy-induced hypertension. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1984 Mar;31(2):210-2.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6704786?tool=bestpractice.com

Management of hypertension

Antihypertensive therapy should be started if systolic BP is persistently between 140 and 159 mmHg and/or diastolic BP is persistently between 90 and 109 mmHg, or if there is severe hypertension (systolic BP ≥160 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥110 mmHg).[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

For ongoing control of hypertension (systolic BP persistently between 140 and 159 mmHg and/or diastolic BP persistently between 90 and 109 mmHg) the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommend oral labetalol, nifedipine, and methyldopa for these individuals.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

Oral monotherapy with one of these three agents is effective in most cases, but some women might require combination therapy. The choice should be based on any preexisting treatment, side-effect profiles, risks (including fetal effects), and the woman's preference.[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

Oral labetalol is the first-line treatment. Oral nifedipine can be used if labetalol is not suitable. Methyldopa is an acceptable alternative if labetalol and nifedipine are not suitable. Some women may require combination therapy. There is no need to reduce the BP too quickly or by too much; the aim is to stop the rise and reduce the BP gradually to a systolic BP of <135 mmHg and diastolic BP of <85 mmHg or less.[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

With severe hypertension (systolic BP ≥160 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥110 mmHg)

For the management of acute-onset, severe hypertension in a critical care setting, intravenous labetalol, intravenous hydralazine, and oral nifedipine can be used first line. Second-line options (e.g., combination therapy, alternative drugs) can be discussed with a specialist if the woman does not respond to first-line therapies.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

[Evidence C]d2bd8c7c-a0c0-449c-9bb9-c26dae15718eguidelineCWhat are the effects of antihypertensive therapy (labetalol, nifedipine, nicardipine, methyldopa, or hydralazine) for the acute management of preeclampsia?[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

Preferred antihypertensive agents

Labetalol is considered the antihypertensive of choice in both acute and nonacute settings, and is effective as monotherapy in 80% of pregnant women.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

[4]Tuffnell DJ, Jankowicz D, Lindow SW, et al. Outcomes of severe pre-eclampsia/eclampsia in Yorkshire 1999/2003. BJOG. 2005 Jul;112(7):875-80.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00565.x

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15957986?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

[Evidence C]07d6cca1-555e-4106-8d21-327a388bc717guidelineCWhat are the effects of labetalol compared with no intervention for the non-acute management of preeclampsia?[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

It seems to be safe and effective for the management of hypertension in pregnant women with preeclampsia; however, it should be avoided in women with asthma or any other contraindication to its use.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

Oral nifedipine may be as effective as intravenous labetalol, and can be considered in cases of deteriorating hypertension previously controlled with oral labetalol.[82]Shekhar S, Gupta N, Kirubakaran R, et al. Oral nifedipine versus intravenous labetalol for severe hypertension during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2016 Jan;123(1):40-7.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1471-0528.13463

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26113232?tool=bestpractice.com

Hydralazine is widely used to manage severe hypertension in pregnancy; however, it can produce an acute fall in BP and should be used along with plasma expansion.[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

Smaller, more frequent doses may be used.

Methyldopa is widely used in lower- and middle-income countries and is an acceptable alternative if labetalol or nifedipine are not suitable.[2]Magee LA, Brown MA, Hall DR, et al. The 2021 International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022 Mar;27:148-69.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35066406?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

[83]Moodley J, Soma-Pillay P, Buchmann E, et al. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy: 2019 national guideline. S Afr Med J. 2019 Sep 13;109(9):12723.

http://www.samj.org.za/index.php/samj/article/view/12723/8990

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31635598?tool=bestpractice.com

[Evidence C]a3173bf5-916d-4450-833e-06d922412764guidelineCWhat are the effects of methyldopa compared with no treatment for the non-acute management of preeclampsia?[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

Methyldopa should be avoided in the postpartum period because of its association with depression; women already taking methyldopa should change to an alternative antihypertensive treatment within 2 days of delivery.[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

[84]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 203: chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Jan 2019 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2019/01/chronic-hypertension-in-pregnancy

Management of eclampsia

Magnesium sulfate is the treatment of choice for women with eclampsia.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

[2]Magee LA, Brown MA, Hall DR, et al. The 2021 International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022 Mar;27:148-69.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35066406?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

Intramuscular or intravenous administration are equally efficacious.[85]Which anticonvulsant for women with eclampsia? Evidence from the Collaborative Eclampsia Trial. Lancet. 1995 Jun 10;345(8963):1455-63.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7769899?tool=bestpractice.com

The ideal dosage of magnesium sulfate remains uncertain, with higher doses recommended in the US.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

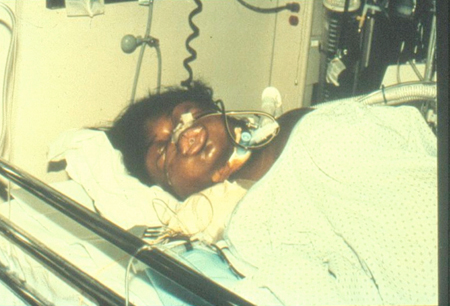

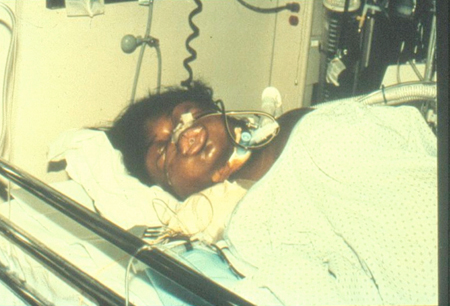

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Patient with severe preeclampsia in intensive care unit post seizureFrom the personal collection of Dr James J. Walker; used with permission [Citation ends].

If a high-dose regimen is used, serum magnesium levels should be checked 6 hours after administration, and then as needed. Therapeutic levels are 4.8 to 9.6 mg/dL (4-8 mEq/L).[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

Respiratory depression may occur and patellar reflexes may disappear once the level reaches 10 mEq/L; calcium gluconate may be used to reverse these effects. A dose reduction may be required in women with renal impairment, as well as more frequent monitoring of serum magnesium levels and urine output.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

The role of magnesium sulfate in prevention of seizures is uncertain.[85]Which anticonvulsant for women with eclampsia? Evidence from the Collaborative Eclampsia Trial. Lancet. 1995 Jun 10;345(8963):1455-63.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7769899?tool=bestpractice.com

In the US, it is recommended for all women with severe preeclampsia.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

In other countries, including the UK, a more targeted approach is recommended, allowing the physician to exercise individual judgment based on the woman's specific risk factors (e.g., presence of uncontrolled hypertension or deteriorating maternal condition).[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

Prolonged use of magnesium sulfate is not recommended

The UK-based Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency recommends against any use of magnesium sulfate in pregnancy for longer than 5 to 7 days. If prolonged or repeated use occurs during pregnancy (e.g., multiple courses or use for more than 24 hours) consider monitoring of neonates for abnormal calcium and magnesium levels and skeletal adverse effects. In 2013, the Food and Drug Administration issued a similar recommendation relating to use of magnesium sulfate as a tocolytic.[86]Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Magnesium sulfate: risk of skeletal adverse effects in the neonate following prolonged or repeated use in pregnancy. May 2019 [internet publication].

https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/magnesium-sulfate-risk-of-skeletal-adverse-effects-in-the-neonate-following-prolonged-or-repeated-use-in-pregnancy

[87]US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: FDA recommends against prolonged use of magnesium sulfate to stop preterm labor due to bone changes in exposed babies. May 2013 [internet publication].

https://www.fda.gov/media/85971/download

Postpartum management

Control of hypertension and seizures must be continued after delivery until recovery is apparent. During this period, the main risk to the mother is fluid overload. Although invasive hemodynamic monitoring is recommended in the US, UK guidelines recommend a fluid-restriction regimen of 80 mL/hour.[1]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 222: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Jun 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2020/06/gestational-hypertension-and-preeclampsia

[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

Limiting maintenance fluids in women with severe preeclampsia/eclampsia has reduced the rate of serious complications and admissions to intensive care units in the UK.[4]Tuffnell DJ, Jankowicz D, Lindow SW, et al. Outcomes of severe pre-eclampsia/eclampsia in Yorkshire 1999/2003. BJOG. 2005 Jul;112(7):875-80.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00565.x

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15957986?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]MBRRACE-UK; Knight M, Bunch K, Tuffnell D, et al. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care: lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland confidential enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity 2015-17. November 2019 [internet publication].

https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/MBRRACE-UK%20Maternal%20Report%202019%20-%20WEB%20VERSION.pdf

Women should be on a fluid input/output chart. Intravenous fluids should be restricted to 80 mL/hour until the woman is drinking freely, as long as urine output is normal. There is no need to treat low urine output, and fluid challenges should not be given except after careful consideration and under strict surveillance. As long as there is cardiovascular stability, adequate urine output, and maintenance of oxygen saturation, there is no need for invasive monitoring.[16]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133

]

Limited data are available regarding the effect of preterm delivery on maternal health.

]

Limited data are available regarding the effect of preterm delivery on maternal health.