Patients present with early-onset ultraviolet radiation (UVR)-induced skin pigmentary changes and UVR-induced damage to the eyes. Those aged <20 years have more than a 1000-fold increased risk of cutaneous malignancies.[24]Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ, Peck GL. Chemoprevention of skin cancer in xeroderma pigmentosum. J Dermatol. 1992 Nov;19(11):715-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1293159?tool=bestpractice.com

Around 25% of patients with XP experience progressive and irreversible neurologic degeneration.[23]Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ, Tamura D. Xeroderma pigmentosum. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; June 20, 2003 [updated 2022 Mar 24].

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1397

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20301571?tool=bestpractice.com

Clinical presentation varies depending on the specific genetic pathologic variant.[20]Piccione M, Belloni Fortina A, Ferri G, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum: general aspects and management. J Pers Med. 2021 Nov 4;11(11):1146.

https://www.doi.org/10.3390/jpm11111146

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34834498?tool=bestpractice.com

A careful clinical examination can differentiate XP from other conditions (e.g., cerebro-oculo-facio-skeletal syndrome, trichothiodystrophy, Cockayne syndrome). See Differentials.

While the diagnosis can be made clinically, unscheduled DNA synthesis testing and genetic testing, where available, confirms the diagnosis and the subtype.[12]Giordano CN, Yew YW, Spivak G, et al. Understanding photodermatoses associated with defective DNA repair: syndromes with cancer predisposition. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov;75(5):855-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27745641?tool=bestpractice.com

As there is no cure for XP, early diagnosis, strict and consistent UVR and daylight protection, and regular cutaneous follow-up to evaluate and treat skin cancers increases life expectancy in patients without neurologic disease.[3]Fassihi H. Spotlight on 'xeroderma pigmentosum'. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2013 Jan;12(1):78-84.

https://www.doi.org/10.1039/c2pp25267h

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23132518?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Giordano CN, Yew YW, Spivak G, et al. Understanding photodermatoses associated with defective DNA repair: syndromes with cancer predisposition. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov;75(5):855-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27745641?tool=bestpractice.com

[25]Bradford PT, Goldstein AM, Tamura D, et al. Cancer and neurologic degeneration in xeroderma pigmentosum: long term follow-up characterises the role of DNA repair. J Med Genet. 2011 Mar;48(3):168-76.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21097776?tool=bestpractice.com

[26]Nakano E, Masaki T, Kanda F, et al. The present status of xeroderma pigmentosum in Japan and a tentative severity classification scale. Exp Dermatol. 2016 Aug;25 Suppl 3:28-33.

https://www.doi.org/10.1111/exd.13082

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27539899?tool=bestpractice.com

Clinical presentation

Consider the diagnosis in a young child (typically <2 years old) with severe and exaggerated sunburn with minimal sun exposure or with early and extensive freckle-like skin lesions (lentigines) in sun-exposed areas.[14]DiGiovanna JJ, Kraemer KH. Shining a light on xeroderma pigmentosum. J Invest Dermatol. 2012 Mar;132(3 pt 2):785-96.

https://www.doi.org/10.1038/jid.2011.426

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22217736?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ, Tamura D. Xeroderma pigmentosum. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; June 20, 2003 [updated 2022 Mar 24].

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1397

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20301571?tool=bestpractice.com

When adults present with XP, they tend to be between 20 and 40 years of age with numerous premalignant or malignant skin cancers.[2]Moriwaki S, Kanda F, Hayashi M, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum clinical practice guidelines. J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;44(10):1087-96.

https://www.doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.13907

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28771907?tool=bestpractice.com

Acute sunburn reaction following minimal UVR exposure is seen in 60% of patients.[3]Fassihi H. Spotlight on 'xeroderma pigmentosum'. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2013 Jan;12(1):78-84.

https://www.doi.org/10.1039/c2pp25267h

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23132518?tool=bestpractice.com

[25]Bradford PT, Goldstein AM, Tamura D, et al. Cancer and neurologic degeneration in xeroderma pigmentosum: long term follow-up characterises the role of DNA repair. J Med Genet. 2011 Mar;48(3):168-76.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21097776?tool=bestpractice.com

This is particularly apparent in patients with subtypes XPA, XPB, XPD, XPF, and XPG.[7]Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-2-5.

https://www.doi.org/10.7573/dic.2022-2-5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35520754?tool=bestpractice.com

Erythema can persist for weeks before resolving.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A child with XP (subtype XPD) at 9 months of age with severe blistering erythema of the malar area following minimal sun exposure. Note the sparing of her forehead and eyes that were protected by a hatBradford PT et al. J Med Genet 2011;48:168-76; used with permission [Citation ends].

Around 40% of patients do not have acute burning with minimal sun exposure. These patients will tan normally and have many lentigines on sun exposed areas (including lips) and an increased skin cancer risk.[23]Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ, Tamura D. Xeroderma pigmentosum. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; June 20, 2003 [updated 2022 Mar 24].

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1397

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20301571?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with subtypes XPC, XPE, and XPV, in particular XPC, show significant exposed-site lentigines.[4]Fassihi H, Sethi M, Fawcett H, et al. Deep phenotyping of 89 xeroderma pigmentosum patients reveals unexpected heterogeneity dependent on the precise molecular defect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Mar 1;113(9):E1236-45.

https://www.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1519444113

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26884178?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-2-5.

https://www.doi.org/10.7573/dic.2022-2-5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35520754?tool=bestpractice.com

XPE and XPV subtypes often present in adulthood with early onset of skin cancer.[4]Fassihi H, Sethi M, Fawcett H, et al. Deep phenotyping of 89 xeroderma pigmentosum patients reveals unexpected heterogeneity dependent on the precise molecular defect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Mar 1;113(9):E1236-45.

https://www.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1519444113

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26884178?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-2-5.

https://www.doi.org/10.7573/dic.2022-2-5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35520754?tool=bestpractice.com

If strict and consistent UVR and daylight protection is not initiated, all patients (i.e., with any of the XP subtypes) will develop chronic cutaneous changes. The history may include progressive dry skin, atrophy, and skin wrinkling.[7]Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-2-5.

https://www.doi.org/10.7573/dic.2022-2-5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35520754?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ, Tamura D. Xeroderma pigmentosum. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; June 20, 2003 [updated 2022 Mar 24].

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1397

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20301571?tool=bestpractice.com

With time, patients develop numerous premalignant and malignant cutaneous neoplasms, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.[7]Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-2-5.

https://www.doi.org/10.7573/dic.2022-2-5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35520754?tool=bestpractice.com

These may be noticed as non-healing wounds, growing papules or nodules on the skin, and/or unusual cutaneous pigmentation. For more information see Basal cell carcinoma, Squamous cell carcinoma, and Melanoma.

Patients <20 years old have a more than 1000-fold increased risk of non-melanoma or melanoma skin cancer.[24]Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ, Peck GL. Chemoprevention of skin cancer in xeroderma pigmentosum. J Dermatol. 1992 Nov;19(11):715-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1293159?tool=bestpractice.com

The average age at onset of first skin cancer is <10 years old.[14]DiGiovanna JJ, Kraemer KH. Shining a light on xeroderma pigmentosum. J Invest Dermatol. 2012 Mar;132(3 pt 2):785-96.

https://www.doi.org/10.1038/jid.2011.426

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22217736?tool=bestpractice.com

The median age of onset of their first non-melanoma skin cancer is 9 years old.[25]Bradford PT, Goldstein AM, Tamura D, et al. Cancer and neurologic degeneration in xeroderma pigmentosum: long term follow-up characterises the role of DNA repair. J Med Genet. 2011 Mar;48(3):168-76.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21097776?tool=bestpractice.com

Premalignant and malignant cutaneous neoplasms are highly suggestive of XP if present within the first decade of life.[7]Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-2-5.

https://www.doi.org/10.7573/dic.2022-2-5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35520754?tool=bestpractice.com

History

Consider whether risk factors are present. Ask if there is a family history of XP and/or parental consanguinity.

XP is an autosomal recessive inherited disorder. Check whether other family members have severe sunburns, early freckling, and/or have developed skin cancer at a young age. Be aware that certain geographical regions have relatively higher incidence of XP (e.g., 45 per million live births in Japan, compared with 1 per million live births in the US).[7]Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-2-5.

https://www.doi.org/10.7573/dic.2022-2-5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35520754?tool=bestpractice.com

Studies have shown that the incidence of XP is increased in countries where consanguinity is common, such as Tunisia, Morocco, Libya and Pakistan.[6]Bhutto AM, Kirk SH. Population distribution of xeroderma pigmentosum. In: Ahmad SI, Hanaoka F, eds. Molecular mechanisms of xeroderma pigmentosum. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. Vol 637. New York, NY: Springer; 2008.[8]Zghal M, El-Fekih N, Fazaa B, et al. [Xeroderma pigmentosum. Cutaneous, ocular, and neurologic abnormalities in 49 Tunisian cases]. [in fre]. Tunis Med. 2005 Dec;83(12):760-3.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16450945?tool=bestpractice.com

[9]Moussaid L, Benchikhi H, Boukind EH, et al. [Cutaneous tumors during xeroderma pigmentosum in Morocco: study of 120 patients]. [in fre]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2004 Jan;131(1 pt 1):29-33.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15041840?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Khatri ML, Bemghazil M, Shafi M, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum in Libya. Int J Dermatol. 1999 Jul;38(7):520-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10440281?tool=bestpractice.com

[11]Bhutto AM, Shaikh A, Nonaka S. Incidence of xeroderma pigmentosum in Larkana, Pakistan: a 7-year study. Br J Dermatol. 2005 Mar;152(3):545-51.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15787826?tool=bestpractice.com

Ask about ocular symptoms.

These may be acute (e.g., photophobia) or chronic (e.g., dry eyes due to conjunctival xerosis).

Eye involvement occurs in around 40% to 90% of patients with XP.[12]Giordano CN, Yew YW, Spivak G, et al. Understanding photodermatoses associated with defective DNA repair: syndromes with cancer predisposition. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov;75(5):855-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27745641?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ, Tamura D. Xeroderma pigmentosum. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; June 20, 2003 [updated 2022 Mar 24].

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1397

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20301571?tool=bestpractice.com

[27]Brooks BP, Thompson AH, Bishop RJ, et al. Ocular manifestations of xeroderma pigmentosum: long-term follow-up highlights the role of DNA repair in protection from sun damage. Ophthalmology. 2013 Jul;120(7):1324-36.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23601806?tool=bestpractice.com

Ask about neurologic symptoms, including developmental milestones and school progress in a child or day-to-day functioning in an adult.

Abnormalities vary in presentation and severity and the age of onset ranges from infancy to adulthood. Worldwide, approximately 25% of patients with XP will develop features of progressive and irreversible neurodegeneration.[24]Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ, Peck GL. Chemoprevention of skin cancer in xeroderma pigmentosum. J Dermatol. 1992 Nov;19(11):715-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1293159?tool=bestpractice.com

A wide range of neurologic manifestations are associated with XP; the most severe include:

Acquired microcephaly[7]Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-2-5.

https://www.doi.org/10.7573/dic.2022-2-5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35520754?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ, Tamura D. Xeroderma pigmentosum. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; June 20, 2003 [updated 2022 Mar 24].

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1397

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20301571?tool=bestpractice.com

Progressive sensorineural deafness[7]Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-2-5.

https://www.doi.org/10.7573/dic.2022-2-5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35520754?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ, Tamura D. Xeroderma pigmentosum. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; June 20, 2003 [updated 2022 Mar 24].

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1397

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20301571?tool=bestpractice.com

[28]Walsh MF, Chang VY, Kohlmann WK, et al. Recommendations for childhood cancer screening and surveillance in DNA repair disorders. Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Jun 1;23(11):e23-31.

https://www.doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0465

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28572264?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Totonchy MB, Tamura D, Pantell MS, et al. Auditory analysis of xeroderma pigmentosum 1971-2012: hearing function, sun sensitivity and DNA repair predict neurological degeneration. Brain. 2013 Jan;136(pt 1):194-208.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/brain/aws317

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23365097?tool=bestpractice.com

Progressive cognitive impairment[7]Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-2-5.

https://www.doi.org/10.7573/dic.2022-2-5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35520754?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ, Tamura D. Xeroderma pigmentosum. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; June 20, 2003 [updated 2022 Mar 24].

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1397

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20301571?tool=bestpractice.com

[28]Walsh MF, Chang VY, Kohlmann WK, et al. Recommendations for childhood cancer screening and surveillance in DNA repair disorders. Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Jun 1;23(11):e23-31.

https://www.doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0465

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28572264?tool=bestpractice.com

Ataxia.[7]Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-2-5.

https://www.doi.org/10.7573/dic.2022-2-5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35520754?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ, Tamura D. Xeroderma pigmentosum. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; June 20, 2003 [updated 2022 Mar 24].

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1397

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20301571?tool=bestpractice.com

Other neurodegenerative manifestations include decreased visual acuity, developmental delay, speech delay, and hyporeflexia.[7]Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-2-5.

https://www.doi.org/10.7573/dic.2022-2-5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35520754?tool=bestpractice.com

While any XP subtype may be affected, neurodegeneration appears to be most common in subtypes XPA and XPD followed by XPB, XPG, and XPF; and least common in XPC, XPE, and XPV.[7]Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-2-5.

https://www.doi.org/10.7573/dic.2022-2-5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35520754?tool=bestpractice.com

Adult-onset neurodegeneration has been reported in patients with mutations in the XPF (ERCC4) gene.[30]Shanbhag NM, Geschwind MD, DiGiovanna JJ, et al. Neurodegeneration as the presenting symptom in 2 adults with xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group F. Neurol Genet. 2018 Jun;4(3):e240.

https://www.doi.org/10.1212/NXG.0000000000000240

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29892709?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical exam

Inspect the skin, looking for acute and/or chronic cutaneous changes. Check for acute changes after minimal sun exposure over sun-exposed areas of skin, such as:

Look for chronic changes of poikiloderma, including:

Early excessive freckle-like lesions (lentigines), especially before age 2 years. These are clinically atypical pigmented lesions that are variable in intensity of brown in color, with irregular shapes, sizes, and borders. This finding is common in XP and rare in the general population.[14]DiGiovanna JJ, Kraemer KH. Shining a light on xeroderma pigmentosum. J Invest Dermatol. 2012 Mar;132(3 pt 2):785-96.

https://www.doi.org/10.1038/jid.2011.426

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22217736?tool=bestpractice.com

Progressive xerosis

Atrophy

Skin wrinkling

Telangiectasia

Signs of cutaneous malignancies, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma, such as:

For more information see Basal cell carcinoma, Squamous cell carcinoma, and Melanoma.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A child with XP (subtype XPC) at age 2 years. Her parents reported that she did not sunburn easily, but she developed multiple hyperpigmented macules on her face. A rapidly growing squamous cell carcinoma or keratoacanthoma grew on her upper lip and a pre-cancerous lesion appeared on her foreheadBradford PT et al. J Med Genet 2011;48:168-76; used with permission [Citation ends].

XP may be diagnosed later in patients with darker Fitzpatrick skin phototypes, as the manifestations of poikiloderma may be less prominent or less noticeable.[31]Plante J, Strat N, Snyder A, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum presenting as a diffuse midline glioma in a patient with skin of color. JAAD Case Rep. 2021 Jul;13:141-3.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.05.030

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34195325?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Poikilodermatous changes of the upper extremity in an 18 year old woman presenting with XP. The changes had been present since early childhood with progressive increase in size and number. A diagnosis of freckles had initially been madePlante J et al. JAAD Case Rep 2021;13:141-43; used with permission [Citation ends].

Examine the eyes. The eyelids and anterior portions of the globe and retina may show evidence of sun damage, such as:[7]Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-2-5.

https://www.doi.org/10.7573/dic.2022-2-5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35520754?tool=bestpractice.com

[27]Brooks BP, Thompson AH, Bishop RJ, et al. Ocular manifestations of xeroderma pigmentosum: long-term follow-up highlights the role of DNA repair in protection from sun damage. Ophthalmology. 2013 Jul;120(7):1324-36.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23601806?tool=bestpractice.com

Pigmentation and atrophy of the eyelids

Ectropion or entropion

Prominent conjunctival injection

Signs of keratitis (painful red, watery eyes)

Clouding of the cornea

Cataracts

Signs of ocular neoplasms of the lids, conjunctiva, or cornea.

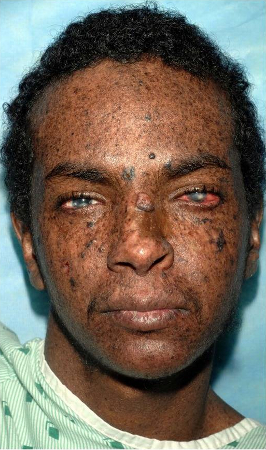

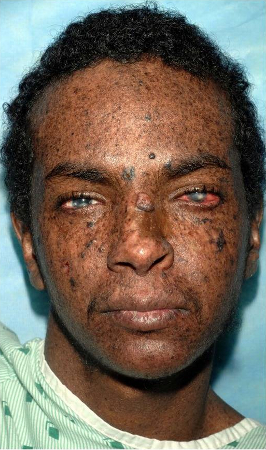

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A 23 year old man from northern Africa with XP (subtype XPC) presenting with numerous hyperpigmented macules on his face. Nodular basal cell cancer is present on his left nasal root. Pigmented basal cell cancer is present on his left cheek. His eyes show corneal scarring from unprotected sun exposureBradford PT et al. J Med Genet 2011;48:168-76; used with permission [Citation ends].

Perform a complete neurologic examination and a neuropsychological assessment to assess for learning disabilities.

Check for signs of neurodegeneration, such as sensorineural deafness, acquired microcephaly, and ataxia.

Be aware that loss of the deep tendon reflexes can be an early sign of neurodegeneration.

Initial investigations

Establish the diagnosis of XP on the basis of clinical findings and family history.

Confirm a definite diagnosis and subtype with unscheduled DNA synthesis from skin biopsy and genetic testing, where available.

Unscheduled DNA synthesis from skin biopsy measures unscheduled DNA synthesis in cultured skin fibroblasts after UV irradiation.[2]Moriwaki S, Kanda F, Hayashi M, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum clinical practice guidelines. J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;44(10):1087-96.

https://www.doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.13907

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28771907?tool=bestpractice.com

Genetic testing identifies biallelic pathogenic variants in one of the causative genes (i.e., XPA, XPB [ERCC3], XPC, XPD [ERCC2], XPE [DDB2], XPF [ERCC4], XPG [ERCC5], or XPV [POLH] genes).[2]Moriwaki S, Kanda F, Hayashi M, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum clinical practice guidelines. J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;44(10):1087-96.

https://www.doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.13907

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28771907?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Giordano CN, Yew YW, Spivak G, et al. Understanding photodermatoses associated with defective DNA repair: syndromes with cancer predisposition. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov;75(5):855-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27745641?tool=bestpractice.com

Molecular genetic testing may include:[23]Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ, Tamura D. Xeroderma pigmentosum. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; June 20, 2003 [updated 2022 Mar 24].

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1397

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20301571?tool=bestpractice.com

Traditionally, serial single-gene testing was used and can still be done, but multigene testing is preferred as preselected genes can be tested on one platform.[23]Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ, Tamura D. Xeroderma pigmentosum. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; June 20, 2003 [updated 2022 Mar 24].

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1397

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20301571?tool=bestpractice.com

If there are existing genetic test results, do not order a duplicate test unless there is uncertainty about the existing result, for example, the result is inconsistent with the patient’s clinical presentation or the test methodology has changed.[32]American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Five things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely, an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. 2021 [internet publication].

https://web.archive.org/web/20230326143738/https://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-college-of-medical-genetics-and-genomics

Consider discussing prenatal diagnosis if there is a family history of XP and the familial pathogenic variants are known. This can be made through DNA testing on cells or fluid obtained from the pregnant mother during chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis.[33]Kleijer WJ, van der Sterre ML, Garritsen VH, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of xeroderma pigmentosum and trichothiodystrophy in 76 pregnancies at risk. Prenat Diagn. 2007 Dec;27(12):1133-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17880036?tool=bestpractice.com