Approach

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) defines upper airway cough syndrome (UACS) as a syndrome characterized by chronic cough (i.e., present for ≥8 weeks) related to upper airway abnormalities.[1]

Central to the diagnosis is the presence of abnormal sensations arising from the throat (e.g., patients may describe something stuck in the throat). As there are no pathognomonic findings or definitive tests to establish a diagnosis, the ACCP recommends that diagnosis should be determined by considering a combination of criteria, including the history, physical exam, imaging (to exclude other causes), and, ultimately, the response to specific therapy. An empiric trial of therapy is considered to be both diagnostic and therapeutic. Improvement or resolution of cough in response to treatment is pivotal to confirming the diagnosis.[1]

History

A thorough history is an important first step in the assessment of any patient with a chronic cough. The initial approach should cover aspects common to the evaluation of any chronic cough, and the physician should first ascertain whether there are any causes that are easily remedied (e.g., medication use). The approach should also focus on identifying red-flag symptoms that warrant further workup (e.g., hemoptysis, chest pain, persistent voice change). These symptoms should arouse suspicion for more serious conditions such as bronchiectasis or lung cancer.

A complete medication history should be taken, as ACE inhibitors are a common cause of chronic cough.[18] An upper respiratory illness (e.g., common cold) is often present.

Seasonal allergen exposure may be a key trigger and should prompt investigation to determine atopic status to seasonal aeroallergens. Certain occupations have been associated with UACS. Common work exposures associated with occupational rhinitis include laboratory animal workers with allergic rhinitis from laboratory animal allergy or nonallergic rhinitis associated with endotoxin exposure; and bakers with allergic rhinitis to wheat, egg, enzymes, or other high-molecular-weight allergens in a bakery.[17]

The character and timing of the cough along with associated features provide important clues towards the underlying cause.[19] Typically, the cough is dry and has been present for at least 8 weeks. In some patients, the cough may be minimally productive; however, a daily productive cough should prompt consideration of pulmonary pathology (e.g., bronchiectasis).

Assess upper airway symptoms

Symptoms are generally nonspecific, and many clinical features overlap with a general cough hypersensitivity syndrome. The key diagnostic feature is an unpleasant sensation in the throat. The description of this symptom can vary; however, it is typically described as an unpleasant feeling in the throat as if something is stuck or lodged there, or is tickling or irritating it. Postnasal drip is a central feature. It is often described as a feeling of mucus dripping from the back of the nose into the throat, and is commonly associated with throat-clearing maneuvers.

Rarely, patients may report a change in voice quality (e.g., dysphonia, hoarseness). This can be considered a feature of UACS; however, other causes should also be considered and ruled out. A clinically relevant overlap between disorders of laryngeal function (e.g., cough, voice disturbance, swallowing difficulty, and the presence of inspiratory wheeze) is increasingly well recognized.[20] A thorough history should therefore explore these aspects of airway "health". Screening questionnaires are now available to highlight the presence of laryngeal hypersensitivity.[21]

Nasal and sinus symptoms

Careful attention should be paid to nasal and sinus symptoms in order to consider if sinus imaging or laryngoscopy is required. Features of rhinitis may coexist and include persistent clear nasal discharge, sneezing, and intermittent nasal blockage. In the context of allergic rhinitis, additional prominent features include nasal pruritus and conjunctivitis. Clinical features such as unilateral nasal symptoms, facial pain, thick green discharge, recurrent nosebleeds, or persistent loss of smell are not typical features of rhinitis and warrant further ENT assessment.[22]

Additional contributory factors

Gastroesophageal reflux may coexist with UACS. Although symptoms of heartburn/indigestion may be self-reported, it is important to be aware that other features (e.g., cough with phonation, on eating, on bending over, or on first becoming ambulatory in the morning) may indicate atypical reflux as a relevant aggravating factor.

Cigarette smoking can be a cause of, or contributing factor to, chronic cough. Active smoking can complicate the evaluation of chronic cough due to UACS and the assessment of response to empiric treatment.

Physical exam

Oropharyngeal exam may reveal visible mucus and a cobblestone appearance to the posterior oropharyngeal wall and local upper airway structures. Intranasal abnormalities (e.g., crusting, mucosal edema) or nasal disease (e.g., edema, polyps) may be noted. Some patients with upper airway abnormalities may have an inspiratory wheeze arising from the glottis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Oropharynx with evidence of generalized edema, enlarged uvula, and some cobblestone change.Image courtesy of Mr Guri Sandhu; used with permission [Citation ends].

Investigations

There are no definitive tests; however, a trial of empiric therapy (i.e., a first-generation antihistamine plus a decongestant) has been recommended to confirm the diagnosis in the presence of a supportive history and exam and imaging that rules out alternative diagnoses. Patients with UACS generally respond to empiric therapy and a response is required for confirmation of the diagnosis according to ACCP criteria.[1]

The following tests should be ordered in all patients:

CBC: may show eosinophilia, which most commonly suggests allergy

Chest x-ray: may show pulmonary pathology

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate or CRP: may indicate the presence of an infection if elevated

Spirometry: may show obstruction/airway disease.

Other tests depend on the patient history, but may include the following:

Serum IgE level: elevated IgE indicates atopy

Specific aeroallergen radioallergosorbent test (RAST): positive RAST indicates atopy

Peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR): may show obstruction/airway disease

Chest computed tomography (CT) with or without contrast: may be appropriate for patients with inconclusive chest x-ray[23]

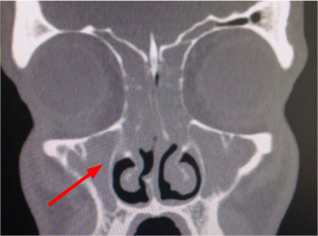

Sinus CT: may show evidence of sinus disease[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT sinus demonstrating opacification.Image courtesy of Mr Hesham Saleh; used with permission [Citation ends].

Direct nasolaryngoscopy: used to identify structural or movement (e.g., paradoxical closure on inspiration) abnormalities, evidence of reflux change, and visible postnasal drip. When performed with provocation (e.g., exposure to perfume) can provide evidence of inducible laryngeal obstruction, which is sometimes termed vocal cord dysfunction.[15]

In UACS, the results of all tests should be normal unless a coexisting condition is present or the cough is due to another etiology.

Bronchoprovocation testing is used to establish a diagnosis of asthma. However, it is increasingly being used to measure extrathoracic hyper-responsiveness (i.e., laryngeal dysfunction). In this context, one series showed that a positive result was common in patients with chronic cough.[24] Further work is needed to establish the clinical value of this test, and it is still considered emerging.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer