Approach

Acute onset of ptosis requires urgent evaluation. Insidious onset is usually related to age-related involutional changes of the eyelid and support structures, or progression of local or diffuse muscular disease.

History

The patient history is the most important aspect of the evaluation of a patient with ptosis. This information will alert the examiner to potentially vision-threatening and life-threatening conditions prior to the physical exam.

A traditional order of interview, beginning with chief complaint and followed by a thorough past medical and surgical history with systemic review of symptoms, is the most fruitful approach.

Pain is sought as a sentinel sign at presentation. The presence of decreased vision, globe proptosis, and significant pain suggests an infectious or inflammatory process. Orbital pain, headache, mental status changes, and vertigo may indicate occult or uncontrolled hypertension and diabetes mellitus, conditions suggestive of stroke as the cause of ptosis.[12] Patients with aponeurotic and involutional forms of ptosis present with symptoms of headache, brow ache, and decreased vision that worsen over the course of the day.[4] Difficulty reading is a common complaint, as ptosis is worse on downgaze.[21]

Adults with the acquired myogenic forms of ptosis may have excessive production of tears, ocular irritation, and corneal exposure secondary to inability to fully close the eye (lagophthalmos) or poor Bell phenomenon (normal upward orbital rotation with eyelid closure).

A history of implanted ophthalmic devices, such as scleral buckles and glaucoma implants, can cause a mechanical ptosis related to implant size or a pseudoptosis secondary to effects on extraocular muscles. Aponeurotic and involutional forms of ptosis are worsened with use of eyelid retraction devices during ocular surgery.[22] Loss of orbital volume secondary to globe pathology (neoplasm) or orbital radiation therapy may also cause ptosis. Previous head and neck or chest surgery (as well as lesions along the sympathetic pathway) suggest Horner syndrome.[13]

Past medical history in young patients or patients with a strong hereditary predilection to basal cell carcinomas may suggest systemic syndromes, such as basal cell nevus syndrome or xeroderma pigmentosum.

Numerous medications can exacerbate ptosis by causing eyelid swelling or through disruption of normal sympathetic tone. Transient ptosis may occasionally complicate botulinum toxin type A treatment of strabismus, blepharospasm, and facial wrinkles.[23][24][25] [

]

]

Cardiopulmonary symptoms of lethargy, palpitations, chest pain, and dyspnea may be presenting signs of diffuse muscular disease as the cause of ptosis. Vasculopathic diseases (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and atherosclerosis) may be accompanied by third nerve palsy and ptosis. Stroke may cause ptosis if the vertebrobasilar circulation is involved.[12]

Congenital forms of ptosis may result from innervational defects during development, such as oculomotor nerve palsy and Horner syndrome. Localized or diffuse muscular dystrophy, such as myotonic dystrophy or oculopharyngeal dystrophy, and mitochondrial myopathies, such as Kearns-Sayre syndrome, can result in acquired myogenic forms of ptosis.[11]

Ptosis may be a result of an underlying autoimmune disorder. Myasthenia gravis often presents with generalized weakness; patients may have undergone thymoma excision.[9] Dysphonia, dysphagia, or shortness of breath and dyspnea should raise suspicion for generalized myasthenia gravis in any patient with inconsistent upper eyelid position and variable diplopia.[9] Systemic autoimmune conditions can present as eyelid infiltration or orbital inflammation with ptosis (e.g., thyroid disease).

Cutaneous dermatologic malignancies can result in ptosis. Patients with prolonged sun exposure are at risk for these cancers, and the eyelid is a common location.

Physical exam

Initial assessment of patients with ptosis includes vital signs and careful inspection of the periorbital area for evidence of infection, trauma, and visual disturbance.

Preseptal soft-tissue edema and erythema with overlying induration is common in infectious and inflammatory etiologies.[26]

Lacrimal gland enlargement associated with orbital inflammatory syndrome, sarcoidosis, and other autoimmune conditions can exacerbate ptosis and present with temporal upper eyelid fullness or a discrete upper eyelid mass. Production of tears may be functionally impaired secondary to ocular irritation or tear outflow obstruction. Orbital cellulitis and orbital malignancies can be secondary to adjacent sinus infections and malignancies, respectively.[20]

The presence of significant orbital trauma may compromise the interrelationship of the eyelid retractors and the soft-tissue and bony attachments. Herniation of orbital fat from an eyelid laceration with or without decreased vision is suspicious for levator muscle and aponeurosis injury and globe perforation. Orbital wall fractures increase the volume of the orbit resulting in enophthalmos and pseudoptosis. Patients with confirmed orbital trauma and high suspicion for globe perforation require urgent ophthalmologic consultation.

Accurate visual acuity readings (distance and near) must be obtained with habitual correction (glasses or contact lenses). If glasses or contact lenses are unavailable, pinhole occlusion devices may be used. If standardized vision screening materials are unavailable, newspaper print, identification badges, or confrontation with fingers or hand movements can be used. Bright colored objects or a light source can be used for preverbal children.

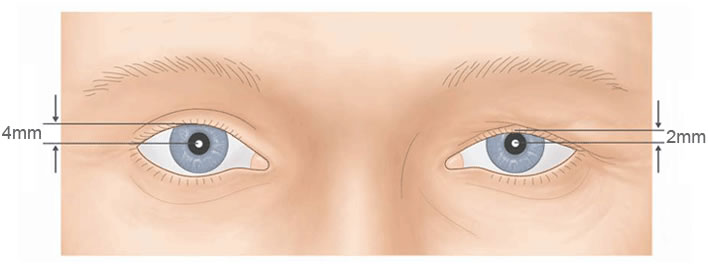

Careful attention is given to a precise pupillary exam under dim illumination. Anisocoria (discrepancy in size of pupils) may reflect disruption of either sympathetic or parasympathetic input. A relative afferent pupillary defect implies significant retinal and optic nerve injury often requiring urgent ophthalmologic consultation. Disruption of the sympathetic input to the superior tarsal muscle induces mild ptosis (1-3 mm), pupillary miosis, and variable anhidrosis. The associated neurologic findings depend on the nature and location of the lesion affecting the sympathetic input.[13] Interruption of normal oculomotor nerve innervation presents with moderate to severe ptosis, pupillary mydriasis, ocular dysmotility, and diplopia secondary to inflammatory, infectious, ischemic, traumatic, and compressive lesions.

Ocular motility should be evaluated using a specific focus of interest (e.g., examiner's finger, pen, light source) in all positions of gaze while recording relative limitations of gaze and subjective diplopia. Dysmotility suggests restriction of movement or paresis secondary to disruption of normal innervational input. Children with myogenic forms of ptosis often adopt a chin-up position to gaze under the ptotic eyelid.

Slit-lamp exam is important for evaluation of intraocular inflammation. Presence of cell and flare (white blood cells floating in milky substance), hypopyon (frank pus), or hyphema (blood) in the anterior chamber may require ophthalmologic referral. Optic disk and funduscopic evaluation should be attempted using a direct ophthalmoscope, if available.

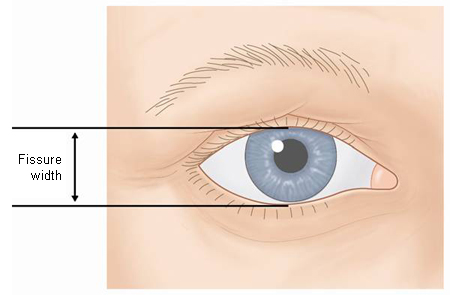

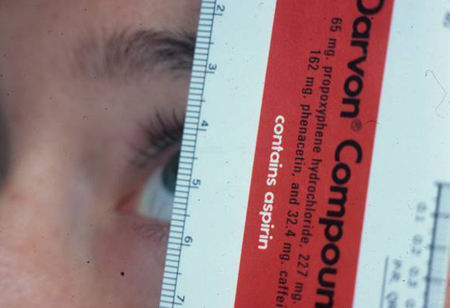

An estimate of the vertical interpalpebral fissure (PF), margin-reflex distance (MRD), and levator function (LF) is helpful to assist in determining the cause of ptosis.[27] In myogenic forms of ptosis, PF, MRD, and LF are decreased. In aponeurotic and involutional forms of ptosis, PF and MRD are decreased and LF is intact. In neurogenic, mechanical, and traumatic forms of ptosis PF, MRD, and LF may be minimally to severely decreased.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Measurement of vertical interpalpebral fissureFrom the collection of Dr Allen Putterman [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Position of upper eyelid in downgazeFrom the collection of Dr Allen Putterman [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Position of upper eyelid in downgazeFrom the collection of Dr Allen Putterman [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Position of upper eyelid in upgazeFrom the collection of Dr Allen Putterman [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Position of upper eyelid in upgazeFrom the collection of Dr Allen Putterman [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Measurement of margin-reflex distanceFrom the collection of Dr Allen Putterman [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Measurement of margin-reflex distanceFrom the collection of Dr Allen Putterman [Citation ends].

Laboratory and specialized testing

A complete blood count with differential is helpful, but not specific, in the assessment of ptosis. Blood cultures are indicated in the presence of an infectious process, and possibly an eyelid culture. In patients with isolated ocular and orbital findings (such as ptosis, proptosis, and strabismus) in which an infectious etiology is unlikely, thyroid function testing and an autoimmune antibody panel is helpful. Check hemoglobin A1c level in older adults with signs and symptoms of a third nerve palsy.[12]

Specialized tests are helpful in tailoring appropriate clinical evaluation for patients with ptosis.

Myasthenia gravis: acetylcholine receptor antibody levels, edrophonium and prostigmine stimulation, electromyographic repetitive nerve stimulation, and the ice-pack test.[28][29]

Multiple sclerosis: MRI brain/spinal cord, lumbar puncture with IgG level assay.

Thyroid eye disease, eyelid or orbital tumors, and globe malposition: Hertel exophthalmometry.[30]

Eyelid laceration: Berke levator function test for intact musculature.

Previous eye-related surgery or implant, fracture, and globe malposition: forced duction testing.

Syphilis: serum fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) and direct fluorescent antibody testing (DFA-TP).

Benign essential blepharospasm: Schirmer testing for tear production.

Horner syndrome: cocaine and hydroxyamphetamine/tropicamide ophthalmic challenges.[31]

Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbits and brain allow precise localization of compressive lesions that cause oculomotor nerve palsies and impairment of sympathetic input.[12] Mechanical forms of ptosis require imaging if the lesion or foreign body is suspected to have orbital involvement. Eyelid edema, secondary to an inflammatory or infectious process with concomitant ocular signs and symptoms or decreased vision, warrants radiologic investigation with contrast.[26]

Orbital imaging is indicated in traumatic forms of ptosis if the eyelid laceration is associated with a deeply embedded foreign body or frank globe trauma. Orbital fracture is not an uncommon association with eyelid laceration, and is evaluated with CT of the orbits without contrast.[32] Orbital imaging with and without contrast may evaluate for soft-tissue and bony abnormalities in cases of pseudoptosis.

CT and MRI of the orbits may be considered in atypical presentations of myogenic, aponeurotic, and involutional forms of ptosis. Patients with a clear etiology of ptosis (without ocular and systemic symptoms) rarely require neuroimaging. The American College of Radiology has produced guidelines on the most appropriate diagnostic imaging tests depending on the clinical presentation.[17]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer