Approach

Most patients with a ventricular septal defect (VSD) will present in infancy and childhood following the detection of a murmur on routine examination. It is unusual for a VSD to present in adults. Most small defects spontaneously close by age 1 to 2 years; most moderate defects have already been diagnosed and treated before adulthood and most large untreated defects result in increased mortality in childhood, and are therefore no longer seen in adults.[11]

If a VSD does present in adulthood, the context is usually one of the following:[2][11]

Restrictive defects that failed to close in childhood but are not hemodynamically important; these pose a risk of endocarditis

Moderate-sized defects not yet closed; these patients typically have mild pulmonary hypertension

Large defects that lead to Eisenmenger syndrome (right-to-left shunt) and are inoperable

Patients who have had their defects closed in childhood but are under follow-up, some of whom may have or develop residual shunting from patch leaks.

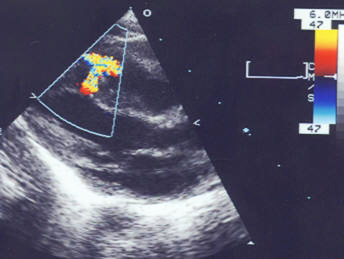

The diagnosis is usually suspected by the detection of a murmur on physical exam and confirmed by echocardiography.[2][11] Chest x-ray and ECG provide supportive evidence of chamber enlargement but are not diagnostic. If the images obtained by echocardiography are inconclusive, or further assessment of complex associated abnormalities is required, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) can be used.[21] Cardiac catheterization is used to confirm the estimation of the shunt in cases where the shunt estimation obtained by echocardiography was inadequate or did not concur with the clinical presentation.[1][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Echocardiographic image of a type 4 (muscular) ventricular septal defect with color flow Doppler showing left-to-right shuntFrom the collection of Dr Kul Aggarwal [Citation ends].

History

There is often a history of a systolic murmur, usually present since birth. The patient may have no symptoms or, in cases of a moderate-sized defect, may develop shortness of breath with exertion as a result of heart failure or faltering growth. If a large, unoperated defect is present, shunt reversal should be suspected if there is a history of recurrent pulmonary infection and signs of cyanotic heart disease.

A VSD secondary to myocardial infarction (MI) presents 3 to 5 days after the initial MI with symptoms of heart failure or, in severe cases, cardiogenic shock.[6] Traumatic VSDs can present at a variety of time frames from immediate to delayed; the presence and severity of symptoms depend on the size of the VSD.[1]

Physical exam

A holosystolic murmur can be heard at the lower left parasternal border. This may be accompanied by a palpable thrill. The pulmonic component of the second heart sound may be loud due to pulmonary hypertension. There may be signs of cardiomegaly, including displacement of the apical impulse downward and laterally on the precordium and, in case of right ventricular hypertrophy, a parasternal heave. Tachypnea may be present in infants who develop heart failure.

Shunt reversal should be suspected if there is evidence of cyanosis, which is sometimes accompanied by clubbing of the nails.

Initial investigations

Echocardiogram

Echocardiography is the investigation of choice to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate the shunt as well as associated abnormalities.[2][11] The defect can be seen on 2D images, and the shunt visualized on color flow imaging. When directed at the defect in the parasternal views, spectral Doppler will show a high-velocity systolic jet based on the gradient between the left ventricle and right ventricle above the baseline in systole. Additionally, chamber sizes can be assessed, and the tricuspid regurgitation jet can be used to determine the pulmonary arterial systolic pressure. In case of a type 1 defect, associated aortic regurgitation can be evaluated. Associated conditions such as tetralogy of Fallot can also be diagnosed. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Echocardiographic image of a type 4 (muscular) ventricular septal defect with color flow Doppler showing left-to-right shuntFrom the collection of Dr Kul Aggarwal [Citation ends].

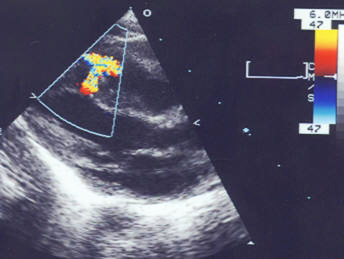

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Echocardiographic image with color flow Doppler showing left-to-right shunting across a type 1 ventricular septal defect at the supracristal (or doubly committed juxta-arterial) levelFrom the collection of Dr Zuhdi Lababidi [Citation ends].

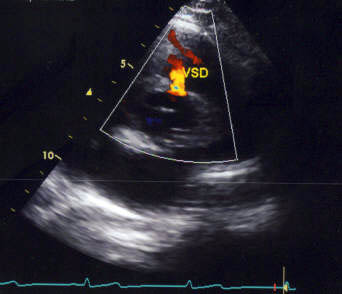

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Echocardiographic image with color flow Doppler showing left-to-right shunting across a type 1 ventricular septal defect at the supracristal (or doubly committed juxta-arterial) levelFrom the collection of Dr Zuhdi Lababidi [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Echocardiographic image with color flow Doppler showing left-to-right shunting across a type 3 ventricular septal defect at the inlet cushion levelFrom the collection of Dr Zuhdi Lababidi [Citation ends].

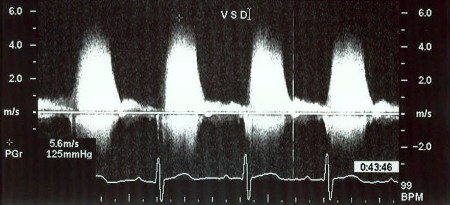

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Echocardiographic image with color flow Doppler showing left-to-right shunting across a type 3 ventricular septal defect at the inlet cushion levelFrom the collection of Dr Zuhdi Lababidi [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Doppler image showing spectral recording of continuous-wave Doppler showing the left-to-right gradient across the ventricular septal defectFrom the collection of Dr Kul Aggarwal [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Doppler image showing spectral recording of continuous-wave Doppler showing the left-to-right gradient across the ventricular septal defectFrom the collection of Dr Kul Aggarwal [Citation ends].

The magnitude of the shunt produced by a VSD is described by the pulmonary-systemic blood flow ratio (Qp:Qs); this measurement is obtained by Doppler echocardiography.

Echocardiography should be ordered in every patient suspected of having a VSD (regardless of whether it is isolated or occurs in the context of a more complex condition) as it helps to establish or confirm the diagnosis, and guides appropriate management. A comprehensive transthoracic echocardiogram is recommended and can also evaluate pulmonary hypertension and any concomitant heart defects.[22][23][24]

Chest x-ray

The chest x-ray may show a normal-sized cardiac silhouette, or show enlargement of the heart. If the shunting is significant, it may be accompanied by prominence of pulmonary vascular markings and pulmonary congestion.

ECG

The ECG may be normal, or may show evidence of left atrial enlargement and left ventricular hypertrophy, or may show biventricular hypertrophy. The ECG is not diagnostic of a VSD, but provides supportive evidence of chamber enlargement (if present).

Subsequent investigations

Cardiac MRI

Although not commonly used in clinical practice for this purpose, MRI is an excellent modality to assess a VSD and also to quantify the shunt. It is reserved for cases with complex defects in need of further assessment, or where echocardiography is inconclusive.

Cardiac CT scanning

Cardiac CT is not a first-line diagnostic test, but can be useful in patients in whom MRI is contraindicated or if MRI shows artifacts from pacemaker leads, for example. It also has the advantage of allowing assessment of coronary arteries.

Right-heart cardiac catheterization

This is usually not needed, and is reserved for cases in which confirmation of shunt estimation is required, usually due to a discrepancy between the clinical presentation and the assessment of the VSD provided by imaging, or because imaging was inadequate in patients with difficult echocardiographic windows.[2]

An oximetric run on cardiac catheterization (continuous monitoring of oxygen saturation as the catheter is moved) will demonstrate a "step-up" in oxygen saturations in the right ventricle (i.e., the right ventricular saturation will be significantly higher than the right atrial saturation due to mixing of oxygenated blood from the left ventricle).

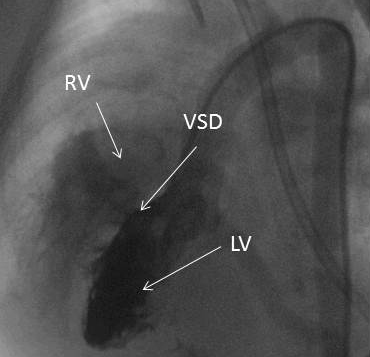

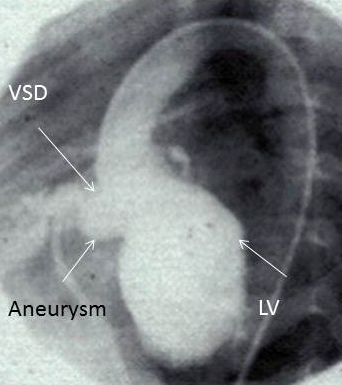

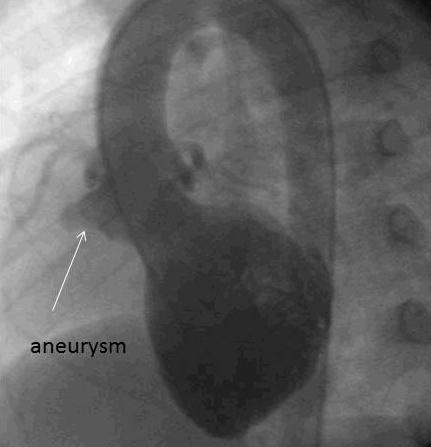

Contrast angiography of the left ventricle will demonstrate the location of the VSD and the site of shunting with contrast going into the right ventricle from the left ventricle. It may also demonstrate the presence of an aneurysm of the ventricular septum.

Pulmonary arterial pressures can be measured to provide an index of pulmonary vascular resistance. This information is useful to assess suitability for surgical correction.

If significant pulmonary hypertension is present, responsiveness to vasodilators (oxygen or nitric oxide) can be used to distinguish reactive from "fixed" pulmonary hypertension; patients whose pulmonary hypertension is reactive may benefit more from surgery.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: X-ray image showing a type 4 (muscular) ventricular septal defect on left ventriculographyFrom the collection of Dr Zuhdi Lababidi [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: X-ray image showing a type 2 (membranous) ventricular septal defect on left ventriculographyFrom the collection of Dr Zuhdi Lababidi [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: X-ray image showing a type 2 (membranous) ventricular septal defect on left ventriculographyFrom the collection of Dr Zuhdi Lababidi [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: X-ray image showing a type 2 (membranous) ventricular septal defect with an aneurysm on left ventriculographyFrom the collection of Dr Zuhdi Lababidi [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: X-ray image showing a type 2 (membranous) ventricular septal defect with an aneurysm on left ventriculographyFrom the collection of Dr Zuhdi Lababidi [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: X-ray angiographic image showing an aneurysm without left-to-right shuntingFrom the collection of Dr Zuhdi Lababidi [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: X-ray angiographic image showing an aneurysm without left-to-right shuntingFrom the collection of Dr Zuhdi Lababidi [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer