Etiology

Central airway obstruction (CAO) is usually classified, based on its etiology, as malignant or nonmalignant. Although the clinical presentation may be similar, malignant and nonmalignant airway compromise should not be considered as a single group, but rather as distinctly different populations.[27][28]

Malignant CAO

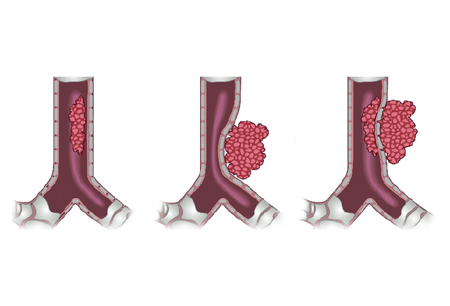

Malignant obstruction of the central airways may occur by 4 mechanisms: extension of an adjacent tumor with airway invasion; a primary intraluminal malignancy; metastatic endobronchial disease; or compression from a contiguous malignant process (e.g., mediastinal malignancies or cancer-related lymphadenopathy).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Central airway obstruction: malignant obstruction of the right mainstemFrom the collections of Jose Fernando Santacruz MD, FCCP, DAABIP and Erik Folch MD, MSc; used with permission [Citation ends].

The most common cause of malignant CAO is direct extension from an adjacent tumor, most commonly bronchogenic carcinoma.[2][3] The most common cell type reported is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which accounts for more than half of the non-small-cell lung cancer related central airway obstructions.[29][30] Approximately 30% of all lung cancer patients will at some point experience endobronchial disease.[31][32] Other tumors commonly associated with adjacent endobronchial invasion include esophageal, laryngeal, and thyroid malignancies.[2]

Primary tumors of the airways are rare. SCC and adenoid cystic carcinoma account for 70% to 86% of all primary tracheal tumors.[33] Other less common primary airway malignancies include carcinoid and mucoepidermoid tumors. Distal to the main carina, carcinoid tumors account for the majority of primary airway malignancies, and approximately 75% of carcinoid tumors present with central endobronchial disease.[2][33][34]

Endotracheal and endobronchial metastases from distant tumors are relatively uncommon. The reported incidence has a very wide range, from 2% to 50% of all pulmonary metastases from extrathoracic neoplasms. This inconsistency is likely related to the variable definitions used. The incidence is much lower when only distant tumors that directly metastasize to the airways are considered.[4][35][36] In one autopsy series of patients with solid tumors, metastatic disease to the central airways occurred in only 2% of cases.[4][33]

The incidence of patients with extrathoracic metastatic endobronchial disease presenting as symptomatic CAO is not known. A wide variety of tumors have been described as directly metastasizing to the airways. Among these, the most common causes include breast, colorectal, renal cell, and thyroid carcinomas.[1][2][35][36]

Nonmalignant CAO

Nonmalignant tracheobronchial obstruction has a wide variety of etiologies, ranging from foreign-body aspiration to ischemia-related lung transplantation bronchial stenosis.

Iatrogenic injury related to an endotracheal tube (ETT) or tracheostomy appears to be the most common cause of benign tracheal strictures.[1][29][37][38]

However, the reported frequency of tracheal stenosis varies widely. If only symptomatic tracheal stenosis (demonstrated by imaging or bronchoscopy) is described, the estimated rate is approximately 2%. The incidence of serious complications related to intubation has significantly decreased since the introduction of high-volume/low-pressure ETTs.[8] It is important to note that the incidence of symptomatic tracheal stenosis after percutaneous tracheostomy is comparable to the incidence following open procedures.[33]

Tracheal obstruction secondary to artificial airways may present as strictures, malacia, or granulation tissue. Following tracheotomy, the stenosis may occur above the stoma, at the stoma, at the cuff site, or at the tip of the tube.[29] Similarly, following endotracheal intubation, the disease may appear at the balloon site or at the end of the tube.

Nonmalignant tumors in the airway are uncommon. The most common benign tracheal neoplasms are squamous cell papillomas, which typically involve the larynx and bronchi, with a relatively uncommon tracheal involvement.[39] Laryngotracheobronchial papillomatosis is an uncommon disease in which multiple squamous cell papillomas occur.[39] Endobronchial and pulmonary dissemination has been reported in 5% of patients with laryngeal papillomatosis and is usually caused by HPV-6 and HPV-11.[33][40][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Tracheal-bronchial papillomatosisFrom the collections of Jose Fernando Santacruz MD, FCCP, DAABIP and Erik Folch MD, MSc; used with permission [Citation ends].

Endobronchial hamartoma is another benign airway tumor that is rarely encountered.[41] Although hamartomas are the most common benign lesions of the lungs, only about 20% present with endobronchial symptoms.[33]

Autoimmune disorders (e.g., granulomatosis with polyangiitis, sarcoidosis, ulcerative colitis) may cause tracheal stenosis.[1]

Tracheobronchial stenosis is also commonly seen after lung transplantation, and bronchial stenosis is the most common airway complication following a lung transplant.[14][42]The incidence has been estimated to be between 1.6% and 32% in different series.[14][42][43] Although it is frequently related to necrosis, dehiscence healing, and endobronchial infection, anastomotic and nonanastomotic bronchial stenosis following lung transplantation may be seen without prior documented airway abnormality. Granulation tissue and tracheobronchomalacia may also cause obstruction of the airways following lung transplant.[14][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Post-lung transplant anastomotic bronchial stenosisFrom the collections of Jose Fernando Santacruz MD, FCCP, DAABIP and Erik Folch MD, MSc; used with permission [Citation ends].

Vascular rings, defined as anomalies of the aortic arch or its branches that compress the central airways, are rare, with an incidence of <0.2%. The most common etiologies of adult vascular rings are double aortic arch and right-sided aortic arch with an aberrant left subclavian artery. The compression of the airway results in malacia and dynamic airway obstruction.[33] Pulmonary artery aneurysm is another vascular cause of tracheobronchial tree compression.

Tracheobronchial strictures may also be related to infectious processes such as tuberculosis (TB) and histoplasmosis. TB typically involves the distal trachea and main-stem bronchi.[44] Histoplasmosis may cause tracheobronchial obstruction by fibrosing mediastinitis or endobronchial granulomas.[7][45]

Although foreign-body aspiration is most frequently seen in children, this condition is also often seen in adults by pulmonologists and emergency room physicians.[17] In adults, most of the episodes occur in the sixth or seventh decade of life and are related to food particles.[46] A number of factors, including alcohol intoxication, sedative or hypnotic drug use, poor dentition, senility, intellectual disability, Parkinson disease, neurologic disorders with impairment of swallowing or mental status, trauma with loss of consciousness, seizures, and general anesthesia commonly predispose patients to aspirate into the airways.[47]

Another rare but potential cause of airway obstruction, especially in hospitalized patients, is related to airway hematoma. The causes of airway hematoma are numerous and include blunt head or neck trauma, foreign-body ingestion, retropharyngeal infection, carotid artery aneurysm, carotid sinus massage, carotid surgery, internal jugular vein catheterization, coagulopathic states, cervical spine trauma and surgery, hyperextension cervical injury, and thyroid fine-needle aspiration.[48][49][50]

Pathophysiology

The basic pathophysiology of CAO is related to an airflow limitation caused by an obstructive etiology. As such, the obstruction may be mechanical or dynamic. Depending upon the degree and location of the obstruction, impairments in oxygenation and ventilation may occur.

Malignant CAO

In malignant obstruction, airway flow limitation may be caused by intraluminal tumor growth, extrinsic airway tumor-related compression, or a combination of both. Malignant cells may access the airway by invasion from an adjacent location or be primary airway malignancies.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Central airway obstruction: malignant obstruction of the right mainstemFrom the collections of Jose Fernando Santacruz MD, FCCP, DAABIP and Erik Folch MD, MSc; used with permission [Citation ends].

In addition, tracheobronchial obstruction due to compression by adjacent tumors or malignant lymphadenopathy has been described.

Nonmalignant CAO

The pathophysiology of nonmalignant causes of CAO is more complex and varies significantly with the specific etiology.

Tracheal stenosis may be the result of high endotracheal tube (ETT) cuff pressure. When the cuff pressure exceeds the mean capillary pressure in the tracheal mucosa (at approximately >20 cm H₂O), obstruction to the capillary blood flow causes inflammation and erosion of the mucosa. This creates necrosis with subsequent destruction of the tracheal architecture and scarring, resulting in stricture formation.[15]

Tracheal lesions may also be related to tracheomalacia due to inflammation, with subsequent thinning and weakening of the tracheal wall.

The endotracheal or tracheotomy tube tip may cause direct traumatic injury to the airway wall, with the subsequent development of granulation tissue-related obstruction.

Tracheobronchial stenosis following lung transplantation is likely to be related to bronchial anastomotic ischemia during the immediate post-transplant period.[51][52] The severe blood flow impairment may lead to ossification, calcification, or fragmentation of any or all bronchial cartilages, resulting in bronchial stenosis or malacia.[14][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Post-lung transplant anastomotic bronchial stenosisFrom the collections of Jose Fernando Santacruz MD, FCCP, DAABIP and Erik Folch MD, MSc; used with permission [Citation ends].

Expiratory central airway collapse may create a flow limitation from excessive narrowing of the trachea and mainstem bronchi during exhalation that results from tracheobronchomalacia or excessive dynamic airway collapse.[13] This type of airway obstruction is often referred to as dynamic or functional stenosis.[21]

Foreign-body aspiration in adults is mostly caused by failure of airway protective mechanisms secondary to diseases or conditions that alter the level of consciousness or create neuromuscular impairments.[47]

The pathophysiology of CAO due to airway hematoma is related to pharyngeal edema and/or direct laryngeal or tracheal compression. Although the trachea is normally rigid and difficult to compress, patients with pre-existing lesions, such as an enlarged thyroid, may be prone to airway obstruction due to an expanding hematoma.[48]

Classification

Malignant vs nonmalignant

Malignant

Primary broncho-pulmonary malignancies[2][3]

Bronchogenic carcinoma (small cell and non-small cell carcinoma of the lung)

Carcinoid tumor

Carcinosarcoma

Pulmonary sarcoma

Salivary gland-type tumor

Adenoid cystic carcinoma

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Endobronchial metastatic disease[4][1]

Bronchogenic carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma

Breast cancer

Thyroid cancer

Colorectal cancer

Sarcoma

Melanoma

Ovarian cancer

Uterine cancer

Testicular cancer

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

Adrenal carcinoma

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia[5]

Mediastinal malignancies[6]

Thymic carcinoma

Thyroid carcinoma

Germ cell tumors (i.e., teratoma)

Laryngeal carcinoma

Esophageal carcinoma

Lymphoma (Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin)

Lymphadenopathy associated with any malignancy

Nonmalignant

Sarcoidosis

Infectious (tuberculosis, histoplasmosis)

Vascular[9]

Vascular ring

Dilated aorta

Aortic aneurysm

Pulmonary artery aneurysm

Cartilage[3]

Relapsing polychondritis

Excessive granulation tissue[9][10]

Endotracheal tubes

Tracheotomy tubes

Airway stents

Foreign bodies

Surgical anastomosis (post-lung transplant)

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis)

Rhinoscleroma (Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis infection)

Benign primary airway tumors[11][12]

Hamartomas

Amyloidosis

Papillomatosis

Endobronchial inflammatory pseudotumor

Tracheomalacia

Bronchomalacia

Excessive dynamic airway collapse

Webs[9]

Idiopathic progressive subglottic stenosis

Tuberculosis

Sarcoidosis

Surgical[14]

Post-heart-lung or lung transplantation (bronchial stenosis, excessive granulation tissue, tracheobronchomalacia)

Sleeve resection of trachea or bronchi

Post-endotracheal intubation or tracheotomy

Burn/smoke injury

Airway hematoma

Tuberculosis

Airway papillomatosis

Rhinoscleroma

Viral or bacterial tracheobronchitis

Diphtheria

Fibrosing mediastinitis (tuberculosis, histoplasmosis)

Epiglottitis

Thyroid gland pathology (goiter, cysts)

Enlarged thymus

Mucous plugs

Mucous ball related to transtracheal oxygen catheters

Vocal cord paralysis

Blood clots

Foreign-body aspiration

Nature of luminal invasion[16][17][18][19][20]

Luminal invasion may be intrinsic, extrinsic, or mixed. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Types of central airway obstruction: intrinsic, extrinsic, and mixedFrom the collections of Jose Fernando Santacruz MD, FCCP, DAABIP and Erik Folch MD, MSc; used with permission [Citation ends].

Intrinsic or endoluminal obstruction:

Airway lumen compromised purely by an endobronchial obstructive process (endobronchial tumor, excessive granulation).

Extrinsic or extraluminal obstruction:

Airway compressed by an extrabronchial lesion (adjacent tumors, lymphadenopathy, thyroid cysts).

Mixed obstruction:

A combination of intraluminal and extraluminal airway obstruction is present.

Structural versus dynamic stenosis[21]

Structural stenosis:

Type 1: Exophytic/intraluminal

Type 2: Extrinsic

Type 3: Distortion

Type 4: Scar/stricture

Dynamic or functional stenosis:

Type 1: Damaged cartilage/malacia

Type 2: Floppy membrane

Dynamic versus fixed upper airway obstruction

Dynamic extrathoracic upper airway obstruction:

Extrathoracic tracheomalacia

Bilateral vocal cord paralysis (post-thyroidectomy, malignancy, neck irradiation)

Vocal cord dysfunction

Neck neoplasm

Subglottic stenosis

Dynamic intrathoracic upper airway obstruction:

Intrathoracic tracheomalacia

Tracheal-bronchial malignancy

Fixed upper airway obstruction:

Tracheal stenosis

Malignancy

Arthritis/ankylosis of cricoarytenoids in rheumatoid arthritis

Juvenile laryngotracheal papillomatosis

Rhinoscleroma (Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis infection)

Subglottic stenosis

Thyroid goiter

Vocal cord stricture

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer