Approach

Establishing the diagnosis of Takayasu arteritis can be difficult, as it may present with nonspecific systemic symptoms including fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Other presenting features may include ischemic symptoms of extremity claudication, transient ischemic attack, stroke, or chest pain. Laboratory tests are nonspecific, reflecting inflammation. Biopsy of involved vessels is not usually feasible, and the diagnosis relies on vascular imaging.[1][2][4][9]

History

In the early stages, constitutional symptoms may include weight loss, low-grade fever, and general fatigue, and these are often ascribed to another cause. The diagnosis of Takayasu arteritis should be considered in patients under age 40 years with symptoms of vascular ischemia. Although relatively uncommon at presentation, claudication in the upper or lower limb may develop over time. Development of collateral circulation patterns can lead to a variety of other findings, especially subclavian steal syndrome caused by a stenotic lesion proximal to the origin of the vertebral artery causing lightheadedness on exercise of the upper limb.

Less common manifestations of Takayasu arteritis include myalgia and arthralgia. Pulmonary arteries are often involved in Takayasu arteritis but rarely cause symptoms. Chest pain, shortness of breath, and hemoptysis may be due to pulmonary artery stenosis, coronary artery involvement, or heart failure from aortic dilation. Pericarditis is possible but uncommon. Involvement of carotid and vertebral arteries can cause cerebral ischemia, which may in turn cause visual symptoms (e.g., diplopia, amaurosis fugax, or scotoma), vertigo, lightheadedness, syncope, or headache. History of a previous transient ischemic attack (TIA), or a TIA as a presenting symptom in a young patient, may indicate inflammation of the vertebral or carotid vessels. Less commonly, the mesenteric vessels may be involved, causing abdominal pain and diarrhea.[1][2][4][9][23][24]

Examination

Careful examination of the vascular system is vital. Cool extremities and absent pulses (most commonly the radial pulse) may be noted, and a difference in blood pressure of >10 mmHg on each arm may be significant. If Takayasu arteritis is suspected, it is advisable to measure the blood pressure on both arms and legs to look for a difference. Hypertension may be a feature, but the blood pressure can also be unusually low if there is a stenosis just proximal to the area of blood pressure measurement. The carotid pulses may feel weaker, and a bruit might be audible. Bruits may also be heard over the supraclavicular region or abdominal aorta. A cardiac murmur may be audible if there is aortic root involvement and aortic regurgitation. Evidence of a previous stroke may suggest central nervous system involvement. The arteriovenous anastomoses seen on examination of the retina and originally described by Takayasu in 1908 are rarely seen today.[1][2][9] Less common manifestations include the appearance of erythema nodosum or pyoderma gangrenosum on the arms or legs.

Investigations

Acute phase markers, including C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), are usually elevated in patients with active disease. They can be followed as markers of disease activity.[1][2][4][9] CRP is preferred to ESR in the acute phase as it has increased sensitivity and specificity to detect acute inflammation.[25] Other nonspecific markers of inflammation such as normocytic anemia and thrombocytosis may also be noted. There are no specific laboratory tests for Takayasu arteritis.

Imaging studies, including computed tomography and magnetic resonance vascular imaging, are important modalities for establishing a diagnosis of Takayasu arteritis and can be helpful in monitoring disease activity.[26] Catheter angiogram is not recommended due to its invasive nature, unless required prior to revascularization procedures.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Magnetic resonance angiogram of the aortic arch and major vessels showing occlusion of bilateral subclavian arteries; left common carotid artery has small diameter; proximal vertebral arteries are not identifiedFrom the collection of Kenneth J. Warrington, MD [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography angiogram, with 3D reconstruction of the aortic arch and major vessels, showing proximal occlusion of the left subclavian artery and patent left vertebral artery distal to the occlusion (left vertebral steal syndrome)From the collection of Kenneth J. Warrington, MD [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography angiogram, with 3D reconstruction of the aortic arch and major vessels, showing proximal occlusion of the left subclavian artery and patent left vertebral artery distal to the occlusion (left vertebral steal syndrome)From the collection of Kenneth J. Warrington, MD [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography angiogram, with 3D reconstruction of the aortic arch and major vessels, showing narrowing of the left common carotid artery and left subclavian arteryFrom the collection of Kenneth J. Warrington, MD [Citation ends].

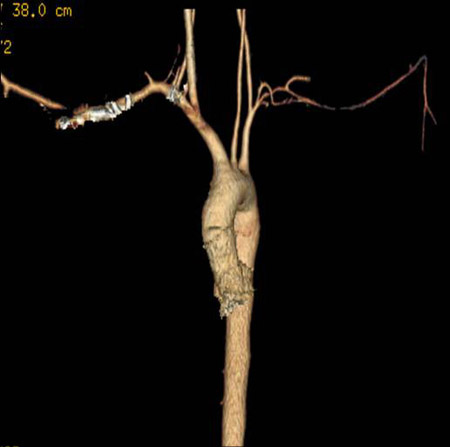

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography angiogram, with 3D reconstruction of the aortic arch and major vessels, showing narrowing of the left common carotid artery and left subclavian arteryFrom the collection of Kenneth J. Warrington, MD [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography angiogram with 3D reconstruction showing bilateral renal artery stenosisFrom the collection of Kenneth J. Warrington, MD [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography angiogram with 3D reconstruction showing bilateral renal artery stenosisFrom the collection of Kenneth J. Warrington, MD [Citation ends].

Positron emission tomography with radiolabeled fluorodeoxyglucose (PET-FDG) can be used to identify inflammation in the large arteries, and is therefore a useful technique to establish diagnosis. PET-FDG can also be used for assessing disease activity over time.[26][27]

Noninvasive vascular ultrasonography is a useful tool for initial evaluation of a patient with suspected Takayasu arteritis.[1][2][9][24][28][29]

Histopathology

Biopsy cannot usually be obtained from one of the vessels typically involved, due to the vessels' size and function as large arteries, and is therefore not part of the usual approach to diagnosis. Biopsy specimens from patients who have undergone revascularization procedures secondary to complications of Takayasu arteritis may show histopathologic findings identical to those of giant cell arteritis. Temporal artery biopsy is not helpful in making the diagnosis.[1][2][9][24]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer