Approach

Dysbarism can largely be diagnosed by a careful history and targeted physical examination alone. Diagnostic testing is rarely required, and may even delay definitive treatment.[1] Presentations of decompression sickness (DCS) are varied and any new symptom that has a close temporal relation to diving should, therefore, be assumed to be due to dysbarism until proven otherwise.

Bubble formation and gas contraction or expansion can occur in many body tissues, and therefore dysbarism often involves multiple organ systems:

Constitutional symptoms are very common, and include extreme fatigue, lethargy, headache, and generalized aches and pains. The vague and disparate nature of these complaints can often lead to delayed presentation (so-called "denial") and/or delayed diagnosis.

Neurologic symptoms may have cerebral, cerebellar, spinal, inner ear, or peripheral nerve manifestations. Nitrogen bubbles rarely disperse in a single anatomical distribution, and so multifocal neurologic manifestations are common.

Musculoskeletal symptoms include pain in one or more joints, or diffuse pain in a muscle. The pain is usually a constant deep boring pain and is often not worsened by range of motion.

Cutaneous symptoms may include pruritus and/or a truncal rash (“Skin Bends”). A cyanotic marbling or reticular rash (Cutis Marmorata) may be seen in more severe forms of DCS.

Lymphatic dysbarism manifests itself as edema, caused by lymphatic obstruction.

Audiovestibular symptoms include hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo.

In the gastrointestinal tract, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramping, or diarrhea are possible. Band-like abdominal pain should raise clinical suspicion for impending serious neurologic involvement.

Cardiopulmonary symptoms include tachypnea, pleuritic chest pain, and cough (known as "the chokes"). Symptoms of local tissue ischemia and hypovolemic shock may follow.

DCS: history

DCS develops during or after ascent from a dive. Most patients develop symptoms within an hour of surfacing from a dive.[1] However, delayed symptom onset may occur. The vast majority of patients will manifest symptoms within 24 hours of surfacing from a dive.[1] Many cases go unreported as a result of failure to seek medical attention, denial, or misdiagnosis. A high index of clinical suspicion is therefore warranted, particularly because there are no diagnostic tools that can exclude the diagnosis reliably.

The history should address specific risk factors for DCS, including:

The dive profile (number of total dives, depth, time, breathing gas, ascent rate). If possible, the clinician should always obtain the patient’s dive computer for review with the hyperbaric physician.

The organ system(s) affected

The time of onset of symptoms (before, during, or after the dive)

The evolution of the symptoms

Some estimation of residual gas load (dives in the preceding 24 hours, breathing gas used, the presence of factors that increase or decrease gas uptake, such as dehydration, exercise, or hot or cold temperature)

A search for other events that might suggest alternative diagnoses (e.g., water conditions/surge, wet suit/dry suit, sea sickness, trauma, marine animal encounters).

Symptoms may be diffuse, and may involve multiple organ systems.

Neurologic symptoms, such as numbness and paresthesia, are most common in the recreational setting.[19]

Audiovestibular symptoms, such as tinnitus, vertigo, ataxia, nausea, vomiting, and a sensorineural hearing loss, are common.

Nonspecific constitutional complaints, such as fatigue, extreme lethargy, headache, and generalized aches and pains, are common and all too often discounted.

Symptoms may also be cutaneous (itchy skin or rashes), lymphatic (e.g., tissue swelling of the breasts or parotid glands), or gastrointestinal (anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, diarrhea). Girdle-like abdominal pain always indicates a spinal cord injury.

Rarely, cardiorespiratory involvement through profuse bubble loading of the pulmonary circulation causes "the chokes," the symptoms of which include tachypnea, tachycardia, cyanosis, pleuritic pain, and an irritative cough.

Symptoms of local tissue ischemia depend on the organ affected.

Barotrauma: history

Barotrauma should be suspected when the circumstances of a dive have not allowed sufficient equilibration between the external environment and the body's gas-containing spaces. This can occur on ascent or descent, and may affect multiple sites in the same diver.[3] The most important anatomical sites affected in divers are the paranasal sinuses, middle ear, inner ear, and lungs, but injuries can also occur to the eyes, skin, bones, teeth, and facial nerve.

The symptoms will depend on the anatomical site. Middle ear barotrauma on descent is common in divers, and can manifest as mild pressure or severe pain. Perforation of the tympanic membrane may occur. The consequent sudden equalization of pressure relieves pain, but vertigo can result from the caloric stimulation of water entering the middle ear space. Middle ear bleeding may extrude into and discharge from the nasopharynx, nostril, or external ear canal. Inner ear barotrauma can often follow, and may cause a sensorineural deafness, tinnitus, and vestibular symptoms such as vertigo, nausea and vomiting, and ataxia.

Pulmonary barotrauma and pulmonary overinflation syndrome almost always occurs on ascent.[3] Symptoms can manifest itself in four ways:

Pulmonary tissue damage, with dyspnea, cough, and hemoptysis immediately after surfacing.

Pneumothorax, with sudden chest pain, dyspnea, and tachypnea.

Mediastinal emphysema, with symptoms that appear rapidly in severe cases or after several hours in milder ones, including a change in voice (hoarseness or a brassy monotone), dyspnea, and dysphagia. This manifestation does not normally require active treatment, although very rarely syncope, shock, or unconsciousness may occur.

Air embolism presenting with immediate, serious, stroke-like neurologic symptoms such as confusion, convulsions, paresis, or loss of consciousness. Any diver with pulmonary barotrauma should have a careful neurologic exam performed due to risk of arterial gas embolism. Arterial gas embolism should be suspected in any diver who experiences loss of consciousness within 15 minutes of surfacing.

Sinus involvement can occur on descent or on ascent. On descent, a feeling of tightness and pressure gives way to pain over the sinuses and often to a more generalized headache. On ascent, blood or mucus may be discharged from the nose or pharynx. The frontal sinus is most commonly affected, but retro-orbital and maxillary pain can also occur. The pain may be referred to the ipsilateral upper teeth. Numbness over the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve has also been reported. Ethmoid and sphenoid sinus barotrauma may only cause a headache that lasts a few hours.

Other, less common symptoms of barotrauma include:

Painful teeth (because gas spaces may exist in infected teeth or near fillings)[24]

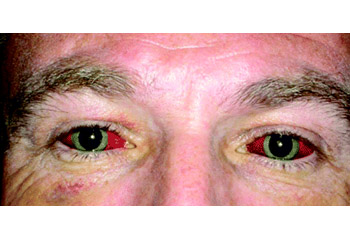

Puffy, edematous facial tissues and conjunctival hemorrhages, caused by trapped air in a diving mask ("mask squeeze") [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ocular barotrauma caused by "mask squeeze"From the collection of Dr. Phillipa Squires, BMJ Education; used with permission [Citation ends].

Linear punctate rashes or bruises, caused by trapped air in dry- or wetsuits ("suit squeeze")

Abdominal discomfort, bloating, burping, and flatus, which may result from gas expansion within the gut on ascent.

DCS: physical exam

DCS is largely diagnosed clinically. A thorough history and physical exam is all that is needed to make the diagnosis.[1][7]

Because neurologic features are common, detailed assessment of this system is mandatory. Neurologic abnormalities are often multifocal, with combinations of signs suggesting damage to the cortex, brain stem, spinal cord, peripheral nerves, or other structures.

Cerebral signs are multiple, and are analogous to those of cerebrovascular disease, although dissimilar in pattern. Dispersion of nitrogen bubbles does not usually a single neurologic distribution, and therefore multifocal neurologic symptoms can be seen.Common features are visual field defects (tunnel vision), monoplegia or hemiplegia, and monosensory or hemisensory disturbances. Mental state examination may reveal deficiencies in cognitive skills.

Cerebellar signs include ataxia (identified by examining romberg, heel-toe gait, finger-nose testing, and heel-shin tests), hypotonia, hyporeflexia, tremor, nystagmus, and dysdiadochokinesis (an inability to perform rapid, alternating movements such as tapping fingers). The sharpened Romberg test is particularly sensitive to subtle neurologic dysfunction.[25] The subject stands heel to toe with the arms crossed so that the flat palms lie across opposite shoulders. Maintenance of this position with the eyes closed is assessed over 60 seconds.

Signs of spinal involvement can include paraplegia, paraparesis, and urinary retention with overflow incontinence. Evaluation and treatment of urinary retention is imperative when caring for an injured diver.

Peripheral nerve involvement may manifest itself with patchy paresthesias, numbness, and weakness (commonly affecting the limbs, sometimes in a "glove-and-stocking" distribution in severe cases).

In musculoskeletal involvement, the affected area may be guarded or held in a position that affords maximal relief of pain. Signs of joint inflammation or effusion are often absent.

Skin manifestations may be local or generalized. Localized skin changes tend to be innocent, and generalized involvement more sinister. A pruritic, often erythematous, rash is common. Some divers have described it as feeling like insects marching on their skin. However, there is significant variation in appearance and description among divers who have suffered from cutaneous DCS. Cutis marmorata (marbling of the skin) is a cyanotic or erythematous mottling of the skin which often signifies more serious DCS.[3] Localized edema secondary to lymphatic obstruction is possible, often over the trunk, and it may track downward to the perineum.

Gastrointestinal manifestations may be seen in severe DCS, which can cause local bowel ischemia and infarction.

Cardiorespiratory signs can include tachypnea with pulmonary rales or crackles and low oxygen saturation indicative of pulmonary edema. Occasionally signs of acute respiratory distress syndrome may be present. In such cases, bradycardia, hypotension, and oliguria herald imminent circulatory collapse.

Barotrauma: physical exam

The signs depend on the site affected. The ears, lungs, and sinuses should be particularly assessed.

In the ear, hemorrhage, or perforation of the tympanic membrane may be observed, as well as free blood or bubbles in the middle ear. Conductive hearing loss may occur and patients should be considered for audiogram in the appropriate clinical setting. Inner ear barotrauma produces vestibular signs such as vertigo, nystagmus, and ataxia. Persistent vertigo or positional sensorineural hearing loss may indicate a perilymph fistula.

An affected sinus may be tender on palpation. Pain may be exacerbated by coughing, sneezing, or holding the head down. Blood is sometimes seen in the mask or nasopharynx. Signs of associated middle ear barotrauma are often present.

Pulmonary barotrauma may result in pneumothorax, which presents with diminished chest wall movements, hyper-resonance to percussion, and diminished breath sounds. Tracheal deviation may indicate a tension pneumothorax.

Mediastinal emphysema or subcutaneous emphysema can also occur. The classic signs are "eggshell crackling" of the skin of the neck and upper chest wall, faint heart sounds, and altered vocal timbre. Hamman sign (crepitus synchronized with heart sounds) indicates pneumopericardium. Left recurrent laryngeal nerve paresis may occur.

Arterial gas embolism (AGE)

AGE is the precipitation of gas bubbles into the arterial circulation. Most commonly in diving, this is due to pulmonary barotrauma, where expanding gas trapped in the lungs causes overdistension and rupture of lung tissue, allowing gas to enter pulmonary vasculature.

Acute neurologic deficits are typical, and may be multifocal in nature, not following any one anatomic distribution. This is due to the wide dispersion of gas bubbles. AGE should be considered in any diver who experiences loss of consciousness within 15 minutes of surfacing.

Nitrogen narcosis

This is a form of inert gas intoxication in which an increased partial pressure of nitrogen causes a syndrome of neurologic and behavioral changes, completely reversible on returning to normal atmospheric pressure. Any patient with ongoing altered mental status in the clinical setting (at normal atmospheric pressure), does not have nitrogen narcosis. There is marked variation between patients in the depth at which nitrogen narcosis is experienced, but most divers will be affected subjectively at 98 feet of sea water (fsw) (30 meters of sea water [msw]). Often the initial symptom is a feeling of mild euphoria and stimulation, similar to alcohol intoxication. Increasing partial pressure produces a progressive impairment in manual dexterity and a deterioration in mental performance. Memory lapses, poor reasoning and judgment, overconfidence, and perceptual narrowing may occur. Confusion, hallucinations, and stupefaction may eventually lead to coma and death.

Investigations

The diagnosis of DCS and arterial gas embolism is clinical and is based largely on history and exam alone. There are no sensitive or specific diagnostic tests, and the choice of any investigations depends on the clinical situation and the differential diagnosis.[1][7]

Neurologic imaging is often obtained in divers presenting with altered mental status, but is often non-diagnostic. A negative head CT or MRI does not exclude arterial gas embolism, as bubbles are rarely seen on imaging. Recompression of injured divers with suspected DCS or AGE should not be delayed in order to obtain imaging studies.

A chest x-ray should be performed if pulmonary barotrauma is suspected.[7] The existence of a pneumothorax may necessitate insertion of a thoracostomy tube. Pneumothorax may worsen by treatment in the recompression chamber, and therefore thoracostomy tube should be placed for pneumothorax prior to treatment. An ECG may be useful in ruling out alternative diagnoses. Echocardiography may be carried out following treatment of decompression sickness in selected cases, as an increased prevalence of patent foramen ovale in these patients has been reported.[26]

Blood tests are not performed routinely in the diagnosis of decompression illness, because none is sensitive or specific. They may be useful in considering differential diagnoses.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer