Approach

Initial evaluation is directed at determining the rapidity and severity of vision loss, whether it is monocular or binocular, and whether there are any associated ocular or systemic symptoms.

Ophthalmological cases commonly present as monocular vision loss. Cases of systemic disease usually present with binocular acute symptoms; it is rare that binocular acute symptoms occur from ocular disease alone.[44]

Rapidity of onset

It is crucial to determine how suddenly symptom onset occurred. Differentiation of rapid from sub-acute or more chronic vision loss is perhaps the most important initial step in determining cause and potential treatments. Once timing is established, the degree and severity of symptoms, as well as symptom location, will guide diagnosis.

Most patients require ophthalmological evaluation, but the urgency of referral will vary. Acute vision loss that occurs suddenly or over the course of several minutes to hours usually requires urgent ophthalmic consultation. People with sub-acute or chronic vision loss (where vision loss has developed over weeks, months, or years) may still need specialist input but usually on a non-urgent basis. Any significant vision loss justifies a call to the ophthalmologist for advice on referral timing.

Clinical presentation

Determining whether symptoms are monocular or binocular is important. Patients with, for example, left homonymous hemianopia may describe the impairment as being localised to the left eye (when in fact the visual field on the left of both eyes is affected).

Sudden monocular vision loss in older patients may indicate giant cell arteritis, while in younger adults it may represent embolic events from coagulation disorders.

The risk of peri-operative ischaemic optic neuropathy may be increased in patients undergoing prolonged procedures, or where substantial blood loss is anticipated, or both.[45] It is prudent to assess these patients pre-operatively in order to adequately advise them that there is a small risk of peri-operative visual loss.[45]

Transient vision loss, whether central or peripheral, is characteristic of a vascular aetiology and should prompt a search for sources of vascular insufficiency.

Sub-acute vision loss requires minimal evaluation in the accident and emergency department or primary care surgery, but typically requires ophthalmologist investigation within a few days.

The presence or absence of pain is often not useful as a diagnostic entity unless the pain is severe.

Associated symptoms of flashes and/or floaters, or recent history of facial trauma, increase the likelihood of retinal detachment.

Past medical history

Chronic medical conditions such as diabetes and hypertension are strongly associated with vision loss from ocular vascular disease. Recent hyperglycaemic episodes may cause refractive error from lens swelling.

It is important to determine whether patients have had previous similar episodes, and whether any permanent sequelae resulted. For example, recurrent episodes of transient vision loss (as in amaurosis fugax) may indicate carotid occlusive disease requiring more aggressive medical or surgical management and referral to neurology and/or vascular specialists.

It is not uncommon for patients to present with vision loss as the initial manifestation of their systemic disease.

Ophthalmic history

Past ocular histories of importance include spectacle and/or contact lens use.

People with myopia and patients who have had cataract surgery are at higher risk of retinal detachment.

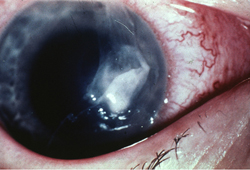

Consider corneal ulceration in contact lens wearers with vision loss and red eye. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Corneal ulcer with epithelial defect and stromal infiltrateFrom Dr Prem S. Subramanian's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

Medication history

A careful medication history is important, as numerous pharmaceutical agents are associated with non-acute vision loss. The patient should also be asked about the use of eye drop medications.

Treatment-induced causes of optic nerve dysfunction can occur secondary to etanercept, isoniazid, ethambutol, tacrolimus, interferon alfa, and radiotherapy.[46][47] Retinal toxicity and vision loss has been reported following prolonged exposure to hydroxychloroquine; vision loss may progress despite discontinuing the medication.[48][49] Digoxin may cause yellowing of vision, and erectile dysfunction drugs may impart transient blue tints.

Use of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors for erectile dysfunction has been associated with increased risk for non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy; study findings are, however, inconsistent.[50][51][52] Amiodarone may cause progressive binocular vision loss.[53]

Physical examination

Initial urgent assessment includes vital sign measurements (including blood pressure and oxygen saturation) and general inspection of head and neck areas for signs of trauma.

Accurate visual acuity readings (distance and near), with patients wearing their habitual glasses or contact lenses, is important. If glasses or contact lenses are not available, pinhole occlusion devices can be used.

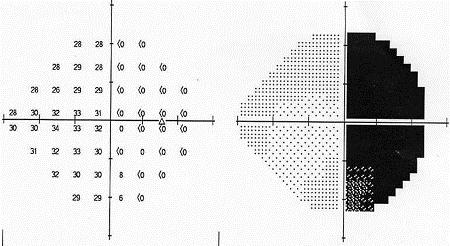

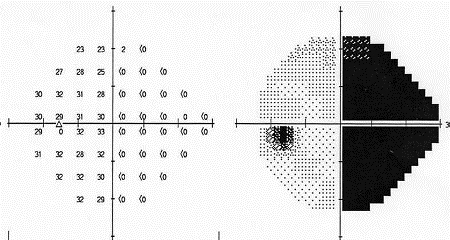

Peripheral vision is tested by confrontation with fingers and/or red test objects. Use of small red objects allows detection of up to 75% of clinically important visual field defects.[54] The presence of homonymous field defects indicates possible stroke and requires urgent inpatient neurological consultation. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Right eye of patient with homonymous field defectFrom Dr Prem S. Subramanian's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left eye of patient with homonymous field defectFrom Dr Prem S. Subramanian's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left eye of patient with homonymous field defectFrom Dr Prem S. Subramanian's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

The presence of relative afferent pupillary defects implies significant retinal or optic nerve dysfunction, making pupil assessment crucial.[42] Consider timely ophthalmology referral.

Poorly reactive pupils may also be seen with bilateral vision loss. Pupillary irregularity or anisocoria do not occur because of vision loss alone and may indicate other processes affecting efferent function, for which referral is also recommended.

Extra-ocular motility assessment can be recorded as full or limited and documented with gross ocular alignment assessment. If abnormal, immediate urgent referral is mandatory.

Eyelid and ocular surface examination with slit lamps may reveal intra-ocular inflammation or blood; corneal irregularity; or cataracts. If slit lamps are not available, penlight examination is adequate for screening purposes.

Good views of optic discs, fundi, and posterior poles (areas within the vascular arcade) provide useful information. However, consider deferring dilated fundoscopy to ophthalmologists so that undilated pupil reactivity can be assessed more formally.

Physical assessment of vision loss in children

Evaluating vision loss in children may require different techniques. Red reflex testing to check for bilateral and symmetric reflexes can provide clues regarding strabismus, refractive errors, or intra-ocular pathology.[55] A pupil examination should be performed. Assessment of visual acuity in pre-verbal children can be accomplished by holding an object before the child and determining if each eye can fixate on the object, maintain fixation, and follow it as it is moved. Older children can be tested using shapes or letters on a standardised card or chart depending on their abilities.

Laboratory tests

The pace of symptom onset determines whether laboratory testing is useful in urgent or primary care settings.

Older patients with sudden monocular vision loss require complete blood counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rates, and C-reactive protein levels.

Patients with transient loss of vision require lipid profiles and complete blood counts.

Consider deferring specific laboratory test selection to ophthalmologists in most sub-acute and chronic cases.

Radiology

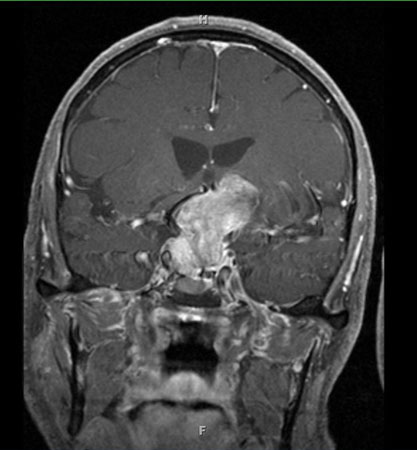

Consider neuroimaging for patients presenting with homonymous hemianopia or other bilateral vision loss suggesting intracranial disease. Computed tomography of the head may exclude acute haemorrhagic events, but magnetic resonance imaging of the brain (with contrast and diffusion-weighted imaging) provides additional detail and may reveal more subtle abnormalities.

Patients with transient symptoms due to ischaemia may require carotid Doppler, other carotid imaging, and/or cardiac echocardiogram.

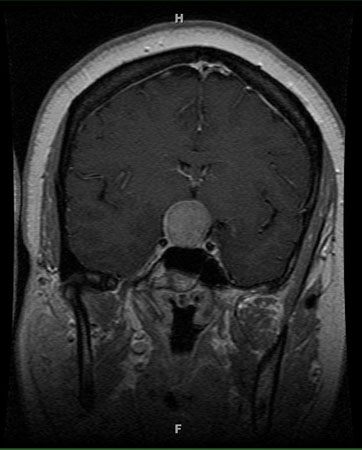

Patients with vision loss and abnormal ocular motility require urgent imaging, paying particular attention to sella turcica regions. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pituitary apoplexy: large suprasellar mass with heterogeneous gadolinium enhancement (T1-weighted MRI)From Dr Prem S. Subramanian's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pituitary tumour: homogenous suprasellar mass elevating and compressing optic chiasm (MRI)From Dr Prem S. Subramanian's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pituitary tumour: homogenous suprasellar mass elevating and compressing optic chiasm (MRI)From Dr Prem S. Subramanian's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer