Approach

Typically, the diagnosis is based on the recognition of systemic manifestations of sepsis, venous congestion of one or both orbits, and injury to the structures within and around the cavernous sinus.[50] An accurate interpretation of these clinical features should alert the clinician to the diagnosis and must be supplemented by imaging and laboratory studies. Presentation in children is similar to that in adults.

The clinical presentation can be:

Acute (e.g., resulting from septic embolisation)

Subacute (e.g., resulting from phlebothrombosis occurring in aseptic cavernous sinus thrombosis [CST]).

The initial presentation can be:

Local (with involvement of the cranial nerves)

Systemic (from extension of the infection into adjacent tissues, causing meningitis, subdural empyema, or pituitary necrosis).

History

A history should include information about:

The presence of any predisposing infection

The timing of onset

The progression of signs and symptoms.

Recent facial, ear, oral, and dental infections or manipulations or a history of maxillofacial surgery or trauma should be sought and may provide clues to a possible underlying primary infection. Risk factors associated strongly with septic CST include recent history of acute sinusitis, history of facial infection, or orbital infection.[40]

The timing of the onset of signs and symptoms of septic CST is variable. The majority of patients present acutely in a toxic state. Less commonly, presentation is more indolent, usually secondary to dental or ear infections. Those cases demonstrate features of septic CST sequentially over several days.[7]

Headache is reported in 50% to 90% of cases of CST.[4] It is the most common early symptom, preceding ocular manifestations, and is demonstrated in patients with sinusitis more frequently than in those with facial infections.[7][15][51] The location of headache may be suggestive. It is usually unilateral, located over the regions innervated by the ophthalmic and maxillary branches of cranial nerve V, involving the retro-orbital or frontal areas, with occasional radiation to the occipital region.[15]

Fever occurs in almost all patients with septic CST and is usually severe.[41] Unilateral peri-orbital oedema, spreading to the contralateral eye in the first 48 hours, is typically seen in septic CST.[4][52] Extra-ocular muscle weakness, exhibited in almost all patients, usually follows chemosis and proptosis. Changes in mental status can develop rapidly, secondary to either central nervous system involvement or sepsis.

Patients with the aseptic form of the disease have a similar but more subtle presentation and do not demonstrate signs and symptoms of sepsis, meningitis, or primary infection. Risk factors strongly associated with the development of aseptic CST include a genetic prothrombotic condition or acquired prothrombotic state. The history should include enquiry about the presence of these factors, as well as other associated features, such as a previous history of arterial or venous thrombosis, a history of cancer, or oral contraceptive use.

Physical examination

In the vast majority of patients, the physical findings of septic CST manifest rapidly.[41] The classic findings of fever, chemosis, proptosis, peri-orbital oedema, and external ophthalmoplegia (restriction of extra-ocular muscles) are present in the majority of patients.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proptosis of the right eye in a patient with cavernous sinus thrombosis secondary to dental infectionJones RG, Arnold B. Sudden onset proptosis secondary to cavernous sinus thrombosis from underlying mandibular dental infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009. pii: bcr03.2009.1671. Used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Patient with bilateral cavernous sinus thrombosis. Note the bilateral proptosis, which is more marked in the right eyeVidhate MR, et al. Bilateral cavernous sinus syndrome and bilateral cerebral infarcts: a rare combination after wasp sting. J Neurol Sci. 2011;301:104-106. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Patient with bilateral cavernous sinus thrombosis. Note the bilateral proptosis, which is more marked in the right eyeVidhate MR, et al. Bilateral cavernous sinus syndrome and bilateral cerebral infarcts: a rare combination after wasp sting. J Neurol Sci. 2011;301:104-106. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ocular manifestations of cavernous sinus thrombosis and their underlying pathologyVisvanathan V, et al. Reminder of important clinical lesson: ocular manifestations of cavernous sinus thrombosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2010; doi:10.1136. Used with permission [Citation ends].

For those who present at an early stage with non-specific symptoms (such as headache), a careful eye and neurological examination, along with thorough cranial nerve testing, is necessary to make the diagnosis.[15] The earliest eye manifestations are caused by venous congestion and include:[4]

Chemosis (conjunctival oedema)

Peri-orbital oedema

Proptosis.

Subsequently, the following signs may follow rapidly, as a result of cranial nerve involvement:

Painful ophthalmoplegia

Ptosis

Mydriasis. This may be mid-size only (owing to sympathetic nervous system involvement in the cavernous sinus), causing internal ophthalmoplegia (blunted papillary response to light).

A lateral gaze palsy may develop before full-blown ophthalmoplegia. This is related to the anatomic position of the sixth cranial nerve. Unlike cranial nerves (CNs) III and IV, protected in a fibrous sheath in the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus, CN VI has an intra-luminal course, making it susceptible to intra-cavernous pathology. The ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve (CN V) may also be affected, leading to a decreased corneal reflex.

The sequential involvement of both eyes is indicative of CST. Nevertheless, even before bilateral eye signs have developed, several signs suggestive of septic CST should be sought, including:

A primary infection site

Profound sepsis

Meningismus (nuchal rigidity, photophobia, and headache)

Early visual impairment

Pupillary defects

Fundoscopic abnormalities (papilloedema and/or retinal vein dilatation) as well as hypo- or hyper-aesthesia in the distribution of the ophthalmic and maxillary nerves.

Frequently, these findings are absent in peri-orbital or orbital cellulitis, for which septic CST is commonly mistaken. Loss of visual acuity is a possible sign, occurring in less than 50% of people with CST.[1] It may be owing to papilloedema; corneal ulceration secondary to proptosis and loss of the corneal reflex; occlusion of the internal carotid, ophthalmic, or central retinal artery; orbital congestion; or an embolic phenomenon. If seizure occurs, it should raise suspicion of intracranial suppuration complicating septic CST.

Rarely, patients may have a more indolent form of septic CST and present with:

Insidious cranial nerve dysfunction

Minimal signs or symptoms of sepsis

Unimpressive ocular manifestations related to venous congestion.

A unilateral isolated lateral gaze palsy is the most early sign in subacute septic CST.[15] Bilateral involvement is a late uncommon finding. This presentation could be explained by a slow progressive obliteration of the cavernous sinus, resulting in a higher degree of compensation than that occurring when the occlusion is rapid. It has been postulated to occur when the infection reaches the cavernous sinus in a retrograde direction, such as in otogenic infection, which was more common in the pre-antibiotic era.[50]

The typical pattern of events in aseptic CST is similar but is slower and less dramatic than that of acute septic CST. Signs and symptoms of sepsis or of a primary infection are absent. Sometimes, it is also difficult to distinguish the aseptic from subacute septic varieties of CST. However, in most cases, aseptic CST is associated with an identifiable predisposing condition, such as hyper-coagulability state, previous sinus surgery, or neoplasms.

Investigations

Although the diagnosis of septic CST may be made correctly on clinical grounds, this condition frequently co-exists with meningitis or orbital infections; hence, the clinical picture may be confusing.[50][53] Therefore, any septic patient who develops focal neurological deficits and orbital signs rapidly requires emergency contrast CT scan and/or MRI of the head to locate the infection.

CT scan and MRI of the head are the primary radiological modalities used to confirm the diagnosis and are also used to assess causal and concurrent pathology.[45][54] Unfortunately, neither modality is entirely sensitive or specific for septic CST. MR venography or CT venography may also be useful to confirm the diagnosis in patients with suspected CST.[54][55][56] However, MRV may miss the diagnosis in the dural venous sinuses.[14] A contrast enhanced CT scan is considered superior to MRI for the detection of early clot formation in the cavernous sinuses, whereas MRI is superior for the rest of the dural venous sinuses.[57] MRI may also be of greatest value for patients with:

Non-diagnostic CT scans

Complications involving the pituitary gland

Complications involving extension of the infection into the brain.

Angiographic extensions of MRI and CT may also be performed.[58]

Laboratory investigations are performed routinely as initial investigations and reveal a marked leukocytosis on FBC in virtually all cases of septic disease.[4] FBC is also helpful to evaluate for polycythaemia as a causative factor and thrombocytopenia, which may suggest thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.[59] Leukocytosis may help to distinguish septic from aseptic disease. Bacteriological confirmation of infection can be obtained from the primary infective source, blood cultures, and concurrent suppuration from relevant, accessible sites.[4] A lumbar puncture may help to exclude meningitis and inform antimicrobial therapy (type and length of therapy) in case a bacterial or fungal agent is isolated.

Initial evaluation of hypercoagulable states includes testing for antiphospholipid syndrome (i.e., tests for antiphospholipid and anticardiolipin antibodies).[45] Additional tests for other common causes of hypercoagulable states are indicated, including factor V Leiden, antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S.[45] However, testing for hypercoagulable states may not be indicated if CST is provoked by strong risk factors e.g., recent history of acute sinusitis or facial infections.[60] Thrombophilia testing should not be performed at the time of a VTE event, as it can be inaccurate.[60] Patients should have completed anticoagulant therapy and should not be taking oral anticoagulants at the time of testing, since vitamin K antagonists will decrease protein S and protein C levels, and direct oral anticoagulants can affect clot-based assay results.[60] Haemoglobin electrophoresis is useful in patients who may have sickle cell disease. Consult a haematologist for specialist advice.

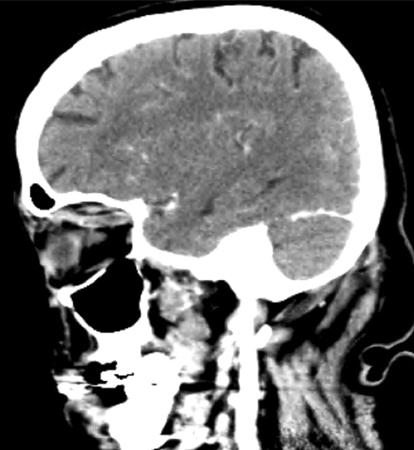

Traditional imaging techniques, namely venography and cerebral angiography, have a limited role in the modern diagnosis of septic CST and may be accompanied by serious complications. The use of conventional x-rays (mastoid plain films, sinus plain films, sinus tomograms) has also declined with the use of CT scanning and MRI.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Sagittal CT scan of the head demonstrating an enlarged, tubular right superior ophthalmic veinJones RG, Arnold B. Sudden onset proptosis secondary to cavernous sinus thrombosis from underlying mandibular dental infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009. pii: bcr03.2009.1671. Used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Post-contrast venous phase CT scan of the head (axial view) showing an enlarged 'S'-shaped right superior ophthalmic vein with associated proptosisJones RG, Arnold B. Sudden onset proptosis secondary to cavernous sinus thrombosis from underlying mandibular dental infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009. pii: bcr03.2009.1671. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Post-contrast venous phase CT scan of the head (axial view) showing an enlarged 'S'-shaped right superior ophthalmic vein with associated proptosisJones RG, Arnold B. Sudden onset proptosis secondary to cavernous sinus thrombosis from underlying mandibular dental infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009. pii: bcr03.2009.1671. Used with permission [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer