Approach

Anaemia should be considered in patients presenting with fatigue, low energy level, pallor, dyspnoea on exertion, or pica, as well as in children with growth impairment.

Universal risk factors include pregnancy, vegetarian/vegan diet, menorrhagia, hookworm infection, chronic kidney disease, chronic heart failure, coeliac disease, gastrectomy/achlorhydria, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. Premature or low birth weight and infant feeding with cows’ milk are risk factors in children.

Patients undergoing surgery who have suspected moderate or severe blood loss (>500 mL), and patients with anaemia identified preoperatively, should be investigated for anaemia.[71]

Clinical evaluation

Key factors in the history specific to IDA include unusual cravings for ice or non-food items (i.e., pica) and restless legs syndrome.

Physical examination findings include glossitis, angular stomatitis, and nail changes (e.g., thinning, flattening, spooning). Non-specific findings on history and physical examination include dyspnoea, fatigue, pallor, dysphagia, exercise intolerance, impaired muscular performance, growth impairment, dyspepsia, hair loss, and cognitive or behavioural issues.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: KoilonychiaReproduced with permission from Bickle Ian. Clinical exam skills: Hand signs BMJ 2004;329:0411402 [Citation ends].

Initial laboratory evaluation with full blood count and peripheral smear

Initial laboratory testing should include a full blood count (including haemoglobin and haematocrit, platelet count, mean corpuscular volume [MCV], mean corpuscular haemoglobin [MCH], mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration [MCHC], red cell distribution width) with peripheral smear, reticulocyte count, and an iron profile.

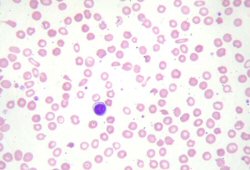

The blood count and smear will show a microcytic (low MCV), hypochromic (increased central pallor) anaemia.

The World Health Organization defines anaemia as: haemoglobin <130 g/L (13 g/dL) in men aged ≥15 years; <120 g/L (12 g/dL) in non-pregnant women aged ≥15 years; and <110 g/L (11 g/dL) in pregnant women.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Peripheral blood smear demonstrating some changes often seen with iron deficiency anaemia. Note that many of the red cells are microcytic (compare size of red cell with the lymphocyte nucleus) and hypochromic (wide central pallor). There are some pencil formsFrom personal collection of Dr Rebecca Fischer Connor; used with permission [Citation ends]. A microcytic hypochromic anaemia can also be seen in thalassaemia and other causes of anaemia; therefore, an iron profile evaluation is required to identify iron deficiency as the cause of anaemia.

A microcytic hypochromic anaemia can also be seen in thalassaemia and other causes of anaemia; therefore, an iron profile evaluation is required to identify iron deficiency as the cause of anaemia.

A reticulocyte count is essential to the work-up of all anaemias. It determines the number of young red cells being produced and released by the bone marrow. Reticulocyte count is low in IDA.

Iron profile evaluation

The following iron profile is consistent with IDA:[12][72][73][74]

Low serum iron

Increased total iron-binding capacity

Transferrin saturation less than 16%

Low serum ferritin (less than 12 nanograms/mL is generally considered diagnostic of IDA, but thresholds vary between guidelines).

Patients with this iron profile do not require further iron tests.

Comments on laboratory evaluation

Many of these tests can be affected by other disorders. For example, ferritin, an acute phase reactant, can be increased in patients with infection or chronic disease (e.g., cancer, autoimmune disorders), which may complicate diagnosis.[74]

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recommends a ferritin cutoff of 45 ng/mL (rather than 15 ng/mL) when ferritin is used to diagnose iron deficiency.[75] The increased ferritin threshold may help to identify patients with IDA in whom inflammation due to rheumatological disease, chronic infections, or malignancy gives rise to increased ferritin levels (>15 ng/mL). The AGA Technical Review Panel concluded that the trade-off between higher sensitivity and lower specificity using the higher threshold of 45 ng/mL provides an acceptable balance of benefits (fewer missed diagnoses) compared with potential harms (additional diagnostic evaluations).[75]

The transferrin receptor-ferritin index can also help diagnose IDA in patients with infection or chronic disease.[76][77] Transferrin receptor is increased in iron deficiency and has a high sensitivity and specificity for IDA.[76][77]

Bone marrow biopsy is the most sensitive and specific test for IDA, but it is not necessary in most cases and is not completely free of error.[4][12] It is usually reserved for patients with unclear serum studies in order to differentiate IDA from anaemia of chronic disease.

Follow-up clinical evaluation

The underlying cause of IDA must always be evaluated. Coeliac serology, urinalysis, and testing for Helicobacter pylori is recommended for all patients.

If coeliac serology is positive or coeliac disease is suspected, it should be confirmed with small-bowel biopsy.[78]

Urinalysis is done routinely in all patients to evaluate blood loss from the renal tract.

A positive H pylori test (i.e., presence of IgG antibodies or faecal antigen associated with H pylori) should be confirmed with a urease breath test or endoscopy with biopsy.[79]

Gastrointestinal tract investigations

Most patients with IDA and no obvious cause will require gastrointestinal (GI) tract investigations.[78] Exceptions may include:

menstruating women

patients with a history of obvious blood loss from another system

patients with hypochromic, microcytic anaemia whose ethnicity increases the risk of thalassaemia, and in whom haemoglobin electrophoresis demonstrates thalassaemia.

Upper and lower GI endoscopy are recommended first-line investigations for men and post-menopausal women with newly diagnosed IDA.[75][78]

If the patient has any upper or lower GI symptoms, the symptomatic part of the GI tract should be investigated first.

If the patient is asymptomatic, both upper and lower GI endoscopy are indicated.

A rectal examination is important and can be done at the same time as lower GI endoscopy. The presence of haemorrhoids as an overt site of bleeding does not preclude further GI examination, which should be performed to look for other proximal lesions (e.g., a neoplasm) in the GI tract.[80]

Computed tomography colonography can be done if colonoscopy is not available or suitable for the patient.[78]

Small-bowel biopsy is advised during upper GI endoscopy (if done), regardless of coeliac serology result. However, it may not be necessary in all patients. For example, if a large bleeding source on colonoscopy is found, then small-bowel biopsy is likely to be of less value. Its use should be determined by the gastroenterologist.

Serological testing should be carried out if autoimmune gastritis is suspected. Patients with positive antiparietal cell or intrinsic factor antibodies should be referred for endoscopic evaluation.[79]

Faecal occult blood tests are generally not useful in evaluation of IDA.[78] If a patient has already been shown to have iron deficiency, a site for potential bleeding must be sought through endoscopy. A faecal occult blood test may; however, be useful in frail patients to screen for GI bleeding to avoid unnecessary invasive testing.[81]

IDA in premenopausal women is not investigated further with GI endoscopy unless the patient is >50 years old; is not menstruating (e.g., following hysterectomy); has GI symptoms or a strong family history of colorectal cancer; or has recurrent or persistent IDA.[78] Referral to a gynaecologist may be required for evaluation of vaginal causes of bleeding.

Emerging tests

Urinary hepcidin is being evaluated as a non-invasive diagnostic tool for IDA in children.[82][74]

Percentage of hypochromic erythrocytes, such as decreased MCH, is a late finding in IDA, and its manual calculation can be time consuming. In contrast, the reticulocyte haemoglobin content decreases within the first few days of IDA. Studies to determine the role of reticulocyte haemoglobin content as a biomarker of IDA are ongoing.[83][84]

Erythrocyte protoporphyrin is the immediate precursor of haemoglobin, and its levels increase when there is insufficient iron available for haemoglobin production.[8] The role of erythrocyte protoporphyrin as a screening tool for iron deficiency is being examined.[85]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer