Disease is usually localised at a single extranodal site.[4]Zucca E, Arcaini L, Buske C, et al. Marginal zone lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020 Jan;31(1):17-29.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.010

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31912792?tool=bestpractice.com

The stomach is most commonly affected (gastric MALT lymphoma).[6]Kiesewetter B, Lamm W, Dolak W, et al. Transformed mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas: a single institution retrospective study including polymerase chain reaction-based clonality analysis. Br J Haematol. 2019 Aug;186(3):448-59.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6771836

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31124124?tool=bestpractice.com

[13]Raderer M, Kiesewetter B, Ferreri AJ. Clinicopathologic characteristics and treatment of marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma). CA Cancer J Clin. 2016 Mar-Apr;66(2):153-71.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21330

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26773441?tool=bestpractice.com

Disseminated disease (including advanced-stage disease) is more common with non-gastric MALT lymphomas (occurring in approximately 25% of patients).[8]Zucca E, Conconi A, Pedrinis E, et al. Nongastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Blood. 2003 Apr 1;101(7):2489-95.

https://www.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2002-04-1279

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12456507?tool=bestpractice.com

Diagnosis is based on history, physical examination, imaging studies, and biopsy (with histopathological, immunophenotypical, and genetic evaluation).

History and physical examination

Patients should undergo a thorough history and physical examination focusing on involved sites. History and findings on physical examination will vary depending on the site of involvement and disease stage.

Gastric MALT lymphoma typically presents with dyspepsia and epigastric discomfort. History may reveal chronic Helicobacter pylori infection. Rarely, abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhoea, malabsorption, vomiting, and B symptoms (unexplained fevers, drenching night sweats, and significant weight loss) may be present.[13]Raderer M, Kiesewetter B, Ferreri AJ. Clinicopathologic characteristics and treatment of marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma). CA Cancer J Clin. 2016 Mar-Apr;66(2):153-71.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21330

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26773441?tool=bestpractice.com

GI bleeding, perforation, and obstruction have been reported infrequently. Lymphadenopathy is an uncommon finding in gastric MALT lymphoma.[30]Olszewska-Szopa M, Wróbel T. Gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2019 Aug;28(8):1119-24.

https://advances.umw.edu.pl/pdf/2019/28/8/1119.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31414733?tool=bestpractice.com

Typical presentation of non-gastric MALT lymphoma varies depending on the involved site:

Salivary/parotid glands: an enlarging salivary gland mass. History may reveal an autoimmune disease (e.g., Sjögren's syndrome or lymphoepithelial sialadenitis).

Ocular adnexa: painless conjunctival injection (red eye) with or without photophobia, mimicking allergic conjunctivitis. Physical examination may reveal orange or salmon-pink masses in the conjunctival fornices. If the orbit is involved, painless proptosis (with or without motility disturbances of the eye), diplopia, ptosis, and, rarely, decreased vision can occur.

Lungs: approximately 40% of patients with lung MALT lymphoma are asymptomatic and present incidentally with a solitary lung nodule on routine chest x-ray.[9]Cohen SM, Petryk M, Varma M, et al. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Oncologist. 2006;11:1100-17.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17110630?tool=bestpractice.com

Symptomatic patients may present with fevers, weight loss, cough, dyspnoea, and haemoptysis.[9]Cohen SM, Petryk M, Varma M, et al. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Oncologist. 2006;11:1100-17.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17110630?tool=bestpractice.com

History may reveal an autoimmune disease (e.g., Sjögren's syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, or common variable immunodeficiency syndrome).

Thyroid gland: thyroid mass; signs and symptoms of oesophageal/tracheal obstruction (dyspnoea, dysphagia, tracheal deviation) can occur if the mass is large. History may reveal Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

Skin: single or multiple papulonodular lesions or plaques that are brown or reddish-brown in colour and are mainly seen over the limbs or back.

Breast: painless, enlarging breast mass.

Dura: focal neurological deficits.

Laboratory assessment

All patients should have a full blood count (FBC) with differential, and blood smear to exclude anaemia (due to GI bleeding), and to assess bone marrow involvement (e.g., if thrombocytopenia is present).

A comprehensive metabolic panel (including LFTs) should be carried out to assess baseline liver and kidney function prior to commencing treatment.[4]Zucca E, Arcaini L, Buske C, et al. Marginal zone lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020 Jan;31(1):17-29.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.010

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31912792?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and beta-2 microglobulin provide an indirect indication of the proliferative rate of the lymphoma (i.e., disease activity), and should be measured as part of the initial work-up to guide diagnosis and prognosis.[14]Walewska R, Eyre TA, Barrington S, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of marginal zone lymphomas: a British Society of Haematology guideline. Br J Haematol. 2024 Jan;204(1):86-107.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.19064

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37957111?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

They are rarely elevated in MALT lymphoma.

Serum protein electrophoresis should be considered because a paraprotein may be detected if there is plasmacytic differentiation, which occurs in around one third of patients.[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[31]Molina TJ, Lin P, Swerdlow SH, et al. Marginal zone lymphomas with plasmacytic differentiation and related disorders. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011 Aug;136(2):211-25.

https://academic.oup.com/ajcp/article/136/2/211/1766046

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21757594?tool=bestpractice.com

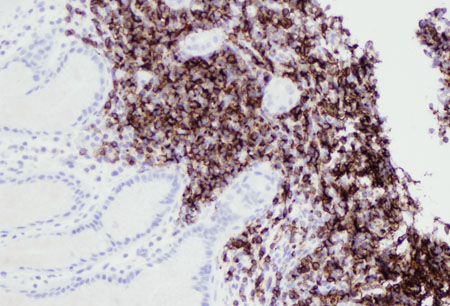

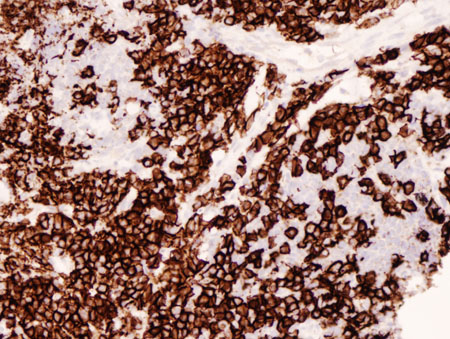

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lung MALT lymphoma: parts of this tumour demonstrate striking plasmacytic differentiation (CD138 staining, ×200)From the collections of Dr R. Joshi and Dr C. McNamara; used with permission [Citation ends].

Upper GI endoscopy

An upper GI endoscopy should be performed if gastric MALT lymphoma is suspected.[4]Zucca E, Arcaini L, Buske C, et al. Marginal zone lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020 Jan;31(1):17-29.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.010

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31912792?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

The endoscopic appearance of gastric MALT lymphoma mimics chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer; therefore, endoscopic biopsy is essential to confirm the diagnosis of gastric MALT lymphoma.

Biopsy

Tissue biopsy specimens should be obtained from abnormal- and normal-appearing areas of an affected site, wherever possible.[14]Walewska R, Eyre TA, Barrington S, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of marginal zone lymphomas: a British Society of Haematology guideline. Br J Haematol. 2024 Jan;204(1):86-107.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.19064

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37957111?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Multiple biopsies may be required if disease is multifocal (e.g., stomach, skin). Fine-needle aspiration biopsy should be avoided as this may not provide an adequate specimen for diagnosis.

Histopathological and immunophenotypical analysis of the biopsy specimens should be carried out to establish a diagnosis.[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

It should be noted that gastric MALT lymphoma preferentially spreads to the splenic marginal zone, where it can remain undetected by conventional histopathological techniques.[32]Cavalli F, Isaacson PG, Gascoyne RD, et al. MALT lymphomas. Haematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2001;241-258.

http://asheducationbook.hematologylibrary.org/cgi/content/full/2001/1/241

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11722987?tool=bestpractice.com

Histological testing (immunohistochemical staining) for H pylori infection should be carried out on biopsy specimens if gastric MALT lymphoma is suspected.[4]Zucca E, Arcaini L, Buske C, et al. Marginal zone lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020 Jan;31(1):17-29.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.010

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31912792?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

In advanced gastric MALT lymphoma with extensive infiltration of the gastric wall, H pylori can be difficult to demonstrate on histological specimens.[33]Nakamura S, Yao T, Aoyagi K, et al. Helicobacter pylori and primary gastric lymphoma: a histopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 237 patients. Cancer. 1997 Jan 1;79(1):3-11.

http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/73502285/HTMLSTART

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8988720?tool=bestpractice.com

If H pylori infection is not confirmed histologically, an alternative (non-invasive) test for H pylori should be carried out (e.g., stool antigen test, urea breath test, serology).[4]Zucca E, Arcaini L, Buske C, et al. Marginal zone lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020 Jan;31(1):17-29.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.010

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31912792?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Walewska R, Eyre TA, Barrington S, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of marginal zone lymphomas: a British Society of Haematology guideline. Br J Haematol. 2024 Jan;204(1):86-107.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.19064

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37957111?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for Chlamydia psittaci, Campylobacter jejuni, and Borrelia burgdorferi may be done on biopsy specimens if non-gastric MALT lymphoma is suspected.[4]Zucca E, Arcaini L, Buske C, et al. Marginal zone lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020 Jan;31(1):17-29.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.010

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31912792?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Walewska R, Eyre TA, Barrington S, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of marginal zone lymphomas: a British Society of Haematology guideline. Br J Haematol. 2024 Jan;204(1):86-107.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.19064

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37957111?tool=bestpractice.com

See Aetiology.

Histological features on biopsy

The usual morphological feature of MALT lymphoma is the infiltration of neoplastic cells around the reactive B-cell follicles outside the preserved mantle zone in a marginal zone distribution, and extending into the interfollicular region.[21]Bacon CM, Du MQ, Dogan A. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma: a practical guide for pathologists. J Clin Pathol. 2007 Apr;60(4):361-72.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2001121

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16950858?tool=bestpractice.com

The morphological features of MALT lymphoma are generally the same across anatomical sites.[34]Laurent C, Cook JR, Yoshino T, et al. Follicular lymphoma and marginal zone lymphoma: how many diseases? Virchows Arch. 2023 Jan;482(1):149-62.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00428-022-03432-2

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36394631?tool=bestpractice.com

There may be certain site-specific differences.

High-grade transformation of MALT lymphoma is characterised by the presence of increased numbers of transformed blast cells with the phenotype of a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). These cases should be formally diagnosed as DLBCL, and the presence of accompanying MALT lymphoma should be noted.

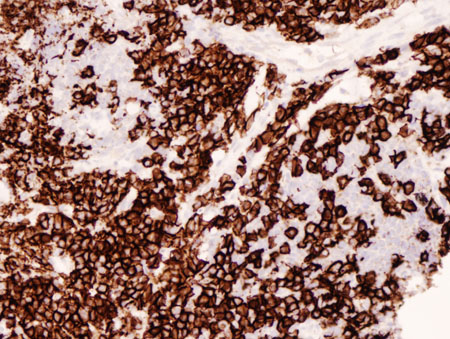

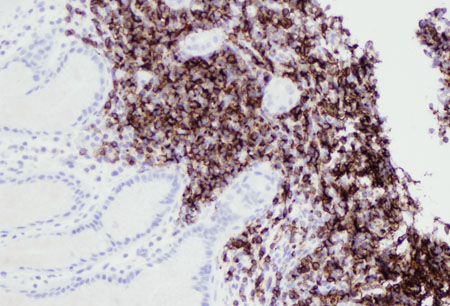

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Infiltrate of lymphoid cells in the lung, confirming their B-cell origin (CD20 staining, ×200)From the collections of Dr R. Joshi and Dr C. McNamara; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lung MALT lymphoma: residual respiratory epithelium has been distorted by infiltrating lymphocytes; the lymphoepithelial lesion (cytokeratin staining, ×200)From the collections of Dr R. Joshi and Dr C. McNamara; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lung MALT lymphoma: residual respiratory epithelium has been distorted by infiltrating lymphocytes; the lymphoepithelial lesion (cytokeratin staining, ×200)From the collections of Dr R. Joshi and Dr C. McNamara; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gastric MALT lymphoma: infiltration of the gastric epithelium by neoplastic B-lymphocytes (CD20 staining, ×200)From the collections of Dr R. Joshi and Dr C. McNamara; used with permission [Citation ends].

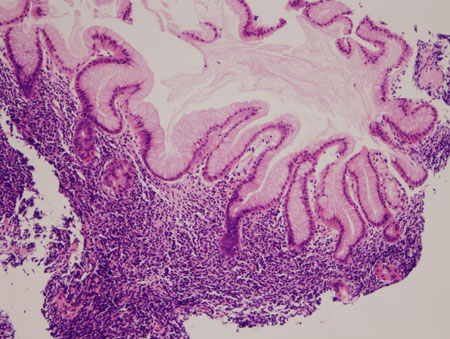

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gastric MALT lymphoma: infiltration of the gastric epithelium by neoplastic B-lymphocytes (CD20 staining, ×200)From the collections of Dr R. Joshi and Dr C. McNamara; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lung MALT lymphoma: lung parenchyma has been replaced by a neoplastic infiltrate of small lymphocytes; a follicle surrounded by neoplastic marginal zone cells can be recognised in the centre of the image (haematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining, ×200)From the collections of Dr R. Joshi and Dr C. McNamara; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lung MALT lymphoma: lung parenchyma has been replaced by a neoplastic infiltrate of small lymphocytes; a follicle surrounded by neoplastic marginal zone cells can be recognised in the centre of the image (haematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining, ×200)From the collections of Dr R. Joshi and Dr C. McNamara; used with permission [Citation ends].

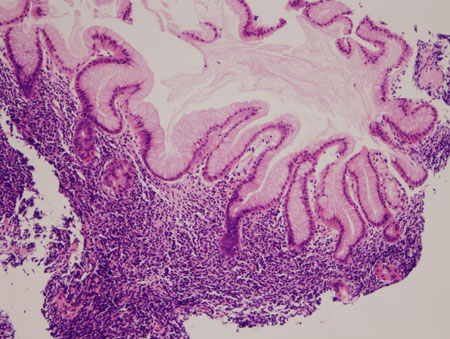

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gastric MALT lymphoma: normal gastric epithelium distorted by a neoplastic infiltrate of lymphocytes extending into the superficial gastric epithelium (haematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining, ×200)From the collections of Dr R. Joshi and Dr C. McNamara; used with permission [Citation ends].

Immunophenotyping

Immunohistochemistry (with or without flow cytometry) of the biopsy specimens should be carried out to identify tumour markers to confirm a diagnosis.[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

The typical immunophenotype for MALT lymphoma is CD5-, CD10-, CD20+, CD23-/+, CD43-/+, cyclin D1-, with BCL2- follicles.[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Genetic studies

Cytogenetic (e.g., fluorescence in situ hybridisation [FISH] and karyotype) and/or molecular (e.g., PCR) evaluation of biopsy samples should be considered to detect cytogenetic abnormalities associated with MALT lymphoma.[4]Zucca E, Arcaini L, Buske C, et al. Marginal zone lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020 Jan;31(1):17-29.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.010

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31912792?tool=bestpractice.com

[18]Sagaert X, De Wolf-Peeters C, Noels H, et al. The pathogenesis of MALT lymphomas: where do we stand? Leukemia. 2007 Mar;21(3):389-96.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17230229?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

t(11;18): mainly detected in gastric and lung MALT lymphoma. Patients with gastric MALT lymphoma who are t(11;18)-positive are unlikely to be positive for H pylori infection and unlikely to respond to H pylori-eradication therapy.[25]Kahl B, Yang D. Marginal zone lymphomas: management of nodal, splenic, and MALT NHL. Haematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2008:359-64.

http://asheducationbook.hematologylibrary.org/cgi/content/full/2008/1/359

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19074110?tool=bestpractice.com

[26]Liu H, Ye H, Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, et al. T(11;18) is a marker for all stage gastric MALT lymphomas that will not respond to H. pylori eradication. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1286-1294.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11984515?tool=bestpractice.com

t(14;18): detected in liver, skin, lung, and ocular adnexa MALT lymphoma

t(3;14): detected in thyroid, ocular adnexa, and skin MALT lymphoma

t(1;14): detected in gastric and lung MALT lymphoma

Other cytogenetic abnormalities that may be detected in MALT lymphoma include trisomy 3 and trisomy 18.[35]Zucca E, Rossi D, Bertoni F. Marginal zone lymphomas. Hematol Oncol. 2023 Jun;41 Suppl 1:88-91.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hon.3152

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37294969?tool=bestpractice.com

Imaging studies

CT scan (contrast enhanced) of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis should be requested in all patients for staging and assessing treatment response.[14]Walewska R, Eyre TA, Barrington S, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of marginal zone lymphomas: a British Society of Haematology guideline. Br J Haematol. 2024 Jan;204(1):86-107.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.19064

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37957111?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

CT scan of the salivary/parotid glands should be ordered if there are symptoms or signs of salivary gland involvement.

18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET/CT scan may be of value for tumour staging and assessing treatment response, but it can lead to false-negative findings due to the low metabolic rate of MALT lymphoma.[30]Olszewska-Szopa M, Wróbel T. Gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2019 Aug;28(8):1119-24.

https://advances.umw.edu.pl/pdf/2019/28/8/1119.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31414733?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Almuhaideb A, Papathanasiou N, Bomanji J. 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in oncology. Ann Saudi Med. 2011 Jan-Feb;31(1):3-13.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3101722

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21245592?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Carrillo-Cruz E, Marín-Oyaga VA, de la Cruz Vicente F, et al. Role of 18F-FDG-PET/CT in the management of marginal zone B cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 2015 Dec;33(4):151-8.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/hon.2181

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25407794?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Albano D, Giubbini R, Bertagna F. 18F-FDG PET/CT and primary hepatic MALT: a case series. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016 Oct;41(10):1956-9.

https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s00261-016-0800-1

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27259334?tool=bestpractice.com

Other imaging studies may be indicated depending on the affected site.[4]Zucca E, Arcaini L, Buske C, et al. Marginal zone lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020 Jan;31(1):17-29.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.010

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31912792?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Walewska R, Eyre TA, Barrington S, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of marginal zone lymphomas: a British Society of Haematology guideline. Br J Haematol. 2024 Jan;204(1):86-107.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.19064

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37957111?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Stomach: endoscopic ultrasound. Particularly useful for evaluating gastric wall infiltration (depth of invasion) and regional lymph node involvement

Large intestine: lower GI endoscopy (colonoscopy)

Orbit or brain: MRI scan. MRI is poor at identifying bone and conjunctival involvement

Breast: mammography, breast ultrasound, and MRI scan

Thyroid: ultrasound

Lung: bronchoscopy

Echocardiogram or multigated acquisition (MUGA) scan should be carried out to assess cardiac function prior to commencing anthracycline-based treatment.[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Other investigations

Screening for coexisting viral infections should be carried out as clinically indicated.[4]Zucca E, Arcaini L, Buske C, et al. Marginal zone lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020 Jan;31(1):17-29.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.010

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31912792?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Walewska R, Eyre TA, Barrington S, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of marginal zone lymphomas: a British Society of Haematology guideline. Br J Haematol. 2024 Jan;204(1):86-107.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.19064

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37957111?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Hepatitis C and B serology: associated with non-gastric MALT lymphoma (e.g., liver). Hepatitis B status should be determined prior to treatment due to risk of virus reactivation during chemotherapy and/or immunosuppressive therapy.

HIV serology: there is a weak association between HIV infection and non-gastric MALT lymphomas (e.g., lung).

Molecular testing and bone marrow biopsy may be considered.[4]Zucca E, Arcaini L, Buske C, et al. Marginal zone lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020 Jan;31(1):17-29.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.010

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31912792?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Walewska R, Eyre TA, Barrington S, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of marginal zone lymphomas: a British Society of Haematology guideline. Br J Haematol. 2024 Jan;204(1):86-107.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.19064

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37957111?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: B-cell lymphomas [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[39]Nakamura S, Aoyagi K, Furuse M, et al. B-cell monoclonality precedes the development of gastric MALT lymphoma in Helicobacter pylori-associated chronic gastritis. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1271-1279.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1858568/pdf/amjpathol00017-0162.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9588895?tool=bestpractice.com

[40]Zucca E, Bertoni F, Roggero E, et al. Molecular analysis of the progression from Helicobacter pylori-associated chronic gastritis to mucosa-associated lymphoid-tissue lymphoma of the stomach. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:804-810.

http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/338/12/804

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9504941?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Treon SP, Xu L, Yang G, et al. MYD88 L265P somatic mutation in Waldenström's macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med. 2012 Aug 30;367(9):826-33.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1200710?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22931316?tool=bestpractice.com

Immunoglobulin gene rearrangement: may help distinguish malignant (clonal) lymphoma from benign (polyclonal) conditions (e.g., hyperplasia, inflammation). In some cases monoclonality can be demonstrated in uncomplicated chronic gastritis, and this may precede the emergence of gastric MALT lymphoma.

MYD88 mutation: may help distinguish MALT lymphoma (with plasmacytic differentiation) from Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia. The MYD88 mutation is common in Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia (over 90%), but it is uncommon in MALT lymphoma.

Bone marrow biopsy and aspirate: to evaluate bone marrow involvement and for staging.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lung MALT lymphoma: residual respiratory epithelium has been distorted by infiltrating lymphocytes; the lymphoepithelial lesion (cytokeratin staining, ×200)From the collections of Dr R. Joshi and Dr C. McNamara; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lung MALT lymphoma: residual respiratory epithelium has been distorted by infiltrating lymphocytes; the lymphoepithelial lesion (cytokeratin staining, ×200)From the collections of Dr R. Joshi and Dr C. McNamara; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gastric MALT lymphoma: infiltration of the gastric epithelium by neoplastic B-lymphocytes (CD20 staining, ×200)From the collections of Dr R. Joshi and Dr C. McNamara; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gastric MALT lymphoma: infiltration of the gastric epithelium by neoplastic B-lymphocytes (CD20 staining, ×200)From the collections of Dr R. Joshi and Dr C. McNamara; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lung MALT lymphoma: lung parenchyma has been replaced by a neoplastic infiltrate of small lymphocytes; a follicle surrounded by neoplastic marginal zone cells can be recognised in the centre of the image (haematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining, ×200)From the collections of Dr R. Joshi and Dr C. McNamara; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lung MALT lymphoma: lung parenchyma has been replaced by a neoplastic infiltrate of small lymphocytes; a follicle surrounded by neoplastic marginal zone cells can be recognised in the centre of the image (haematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining, ×200)From the collections of Dr R. Joshi and Dr C. McNamara; used with permission [Citation ends].