Approach

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is an uncommon, but underdiagnosed, condition, and the diagnosis should be considered in asthma and cystic fibrosis (CF) patients with poorly controlled respiratory symptoms, frequent exacerbations, and/or worsening lung function. Patients characteristically present with increased wheezing, productive cough with expectoration of mucus plugs, and shortness of breath. Systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, and weight loss may sometimes be present. In some patients, particularly in CF, symptoms may be difficult to distinguish from their baseline chronic respiratory symptoms.[20]

Timely diagnosis and treatment is important to prevent the progression of ABPA to chronic respiratory complications such as bronchiectasis, fibrosis, cavitary lung disease, and chronic respiratory failure.[22]

Clinical findings

Clinically, the patient typically presents with worsening control of asthma or CF or recurrent respiratory exacerbations, including symptoms of wheezing, productive cough, increase in sputum production, mucus plugging, and shortness of breath. In more severe cases, patients may present with symptoms such as malaise, low-grade fever, pleuritic chest pain, and haemoptysis.[5][7]

Physical examination may demonstrate end-expiratory wheezes, rhonchorous breath sounds, and cough. In advanced disease, digital clubbing, cyanosis, or features of cor pulmonale (peripheral oedema, splitting of the second heart sound, left parasternal or subxiphoid heave, ascites, hepatojugular reflux, and pulsatile liver) may be present; however, such end-stage presentations of ABPA are quite uncommon in modern medicine.

Investigations

If clinical suspicion for ABPA is high, then laboratory investigations and/or skin testing skin allergy testing are performed to assess for allergic Aspergillus sensitisation and hypersensitivity. High-resolution CT of the chest might additionally be ordered to assess for characteristic radiographic findings of ABPA.

Skin testing

Initial skin testing for Aspergillus sensitisation is performed via a skin prick test; a positive result is indicated by an immediate cutaneous wheal-and-flare reaction relative to a positive control (e.g., histamine) and negative control (e.g., saline), indicative of type I hypersensitivity to Aspergillus antigens.

Negative skin prick results are typically confirmed with an intradermal test, which involves a slightly deeper injection of allergen into the dermis and has a higher sensitivity compared to the skin prick test.[23] The sensitivity of Aspergillus skin testing for ABPA is very high (>95% in prior studies), but the specificity is relatively low. Studies report that only 25% to 37% of patients with a positive Aspergillus skin test end up meeting full criteria for ABPA.[7]

Laboratory investigations

In practice, serological markers of allergic hypersensitivity to Aspergillus, including total serum IgE and Aspergillus-specific IgE, are typically sent concurrently or in lieu of Aspergillus skin testing.

IgE levels are significantly higher in patients with ABPA than in those with asthma, who have only a positive skin test to A fumigatus, and in normal controls.[24] If serum total IgE is between 200 and 500 kilounits/L for a patient with CF, the serum IgE test is repeated. If suspicion is high, then other diagnostic tests, such as Aspergillus-specific IgE and serum precipitating antibodies (serum precipitins) to A fumigatus, should be considered.[25] In practice, patients with ABPA almost always have IgE levels greater than 500, with few caveats.

Aspergillus-specific IgE is elevated in ABPA, reflecting the type 1 immune response.[1] In the absence of skin test results, an elevated Aspergillus-specific IgE, supported by an elevated total IgE, detectable Aspergillus-specific IgG, and eosinophilia are serological markers of ABPA.[26] The combination of elevated total serum IgE and elevated specific IgE to recombinant Aspergillus allergen f4 and/or recombinant Aspergillus allergen f6 allows classic ABPA to be diagnosed with 100% specificity and 64% sensitivity, and with a 100% positive predictive value and 94% negative predictive value.[27]

A full blood count is indicated to assess the peripheral blood eosinophil count. In the absence of oral corticosteroid use (which can lower eosinophil counts), peripheral eosinophilia has been reported in 43% to 100% of cases a total eosinophil count of over 500 is one of the diagnostic criteria for ABPA in patients with asthma.[28][29]

Imaging studies

Chest x-ray is usually undertaken early in the work-up of chest symptoms. Although not essential for the diagnosis of ABPA, when a chest x-ray is obtained as part of an evaluation infiltrates may be visible, commonly involving the upper or middle lobe.[1] These findings may be transient or permanent. If serum eosinophilia is present at the same time, the lung infiltrates may be termed pulmonary eosinophilia. Mucus plugging and signs of bronchiectasis may also be noted.[1]

High-resolution CT of the chest detects whether central bronchiectasis (i.e., occurring within the inner two-thirds of the lungs) is present.[1][30] Additional findings that may be noted on chest CT include mucus plugging of the bronchi (finger-in-glove appearance) or bronchiolar mucus impaction (tree-in-bud shadow), pulmonary infiltrates, and peribronchial thickening.[1] High-attenuation mucus, that is mucus which is visually denser than paraspinal skeletal muscle, or measuring >70 Hounsfield units, is considered the closest things to a pathognomonic sign for ABPA, and has 100% specificity. When present at the time of diagnosis it also predicts poor outcomes.[31][32]

Investigations to consider

Sputum culture and microscopy are often performed, but are not a diagnostic requirement. In ABPA, mucus plugs are present on gross examination, with evidence of A fumigatus fungal elements and eosinophils on microscopy.[25]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray in a patient with ABPA: ring shadows (long arrows) represent bronchiectatic airways seen in cross-section; tram lines (short arrow) seen longitudinallyFrom American College of Chest Physicians, PCCU Volume 17, Lesson 17: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray in a patient with ABPA: classic glove-finger pattern represents central bronchiectatic airways impacted with mucusFrom American College of Chest Physicians, PCCU Volume 17, Lesson 17: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; used with permission [Citation ends].

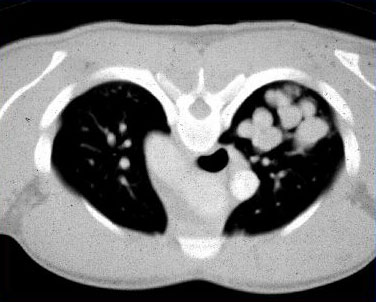

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray in a patient with ABPA: classic glove-finger pattern represents central bronchiectatic airways impacted with mucusFrom American College of Chest Physicians, PCCU Volume 17, Lesson 17: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT chest in a patient with ABPA: dilated, mucoid-impacted bronchiectatic airwaysFrom American College of Chest Physicians, PCCU Volume 17, Lesson 17: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT chest in a patient with ABPA: dilated, mucoid-impacted bronchiectatic airwaysFrom American College of Chest Physicians, PCCU Volume 17, Lesson 17: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT chest in a patient with ABPA: glove-finger shadow due to mucoid impaction in central bronchiectasis in a patient with asthmaFrom The Radiology Assistant: Chest - HRCT Part 1; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT chest in a patient with ABPA: glove-finger shadow due to mucoid impaction in central bronchiectasis in a patient with asthmaFrom The Radiology Assistant: Chest - HRCT Part 1; used with permission [Citation ends].

Diagnostic criteria

Multiple criteria for diagnosing ABPA have been established, including the Rosenberg-Patterson criteria (1977), the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) consensus criteria (2003), and the International Society of Human and Animal Mycology (ISHAM) working group criteria (2013), as well as the Modified ISHAM criteria (2022).[29][33][34]

There is no universally validated criteria; however, the ISHAM criteria are the most widely accepted and utilised at this time for patients with asthma.[29] A new 10-point criteria was proposed by the Japan ABPM Research Program for diagnosing the broader spectrum of ABPM (allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis, including the less common non-Aspergillus filamentous fungi) in patients without cystic fibrosis.[35] For CF, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation consensus criteria (2003, reaffirmed 2021) remains the most commonly used definition for diagnosis (see Diagnostic criteria for more information).[34]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer