Approach

The history and physical examination are of primary importance in the diagnostic approach. Determining the cause involves considering both clinical and chronological features. Patients often reveal the cause of the rash in their historical recollection of events before its appearance. For example, a mother reports several children in the neighbourhood have been unwell with a 'bug' then developed a rash (e.g., viral exanthem), or an older patient first notices the rash after a visit to a new doctor (e.g., drug eruption).

Age, sex, family history, medications, known allergies, and exposures are also of primary importance. Age may be the single most important predictive factor of diagnosis. In the absence of other data, maculopapular rash in adults is most likely drug-related, while maculopapular rash in children is most likely viral-related.[98]

History should include:

Medicines

Immunisation record

Ill contacts

Travel.

Clinical features should be noted with the initial survey of the patient:

Primary lesion morphology, number, and distribution

Duration of symptoms

Mucous membranes involved or spared

Associated signs and symptoms (e.g., fever, pruritus, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly).

Lesion morphology, number, and distribution

Lesions are typically erythematous or reddened, due to the presence of inflammation.

Commonly, the eruption is a combination of macules, papules, patches, plaques, and even other morphologies, though one morphology may predominate.

Lesions can be dusky red or purple in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Lesions in secondary syphilis are pink to red-brown, ranging from 2 to 20 mm in diameter.

Erosions may be seen in severe cutaneous drug eruptions, prior to cutaneous necrosis.

Petechiae may occur in enteroviral, echoviral, Epstein-Barr virus, and Ebola virus infections, and in dengue haemorrhagic fever, meningococcaemia, rickettsial diseases, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and toxic shock syndrome.

Urticarial eruptions occur in anaphylaxis. Acute hepatitis B and C, insect bites or stings, and non-immediate adverse reactions to iodinated contrast media may also cause urticaria.

Vesicles might occur in hand-foot-and-mouth disease, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and congenital syphilis.

Eruption begins on the face and progresses cephalocaudally in rubella and measles. In measles, the eruption may start behind the ears.

Rash appears abruptly on the trunk after defervescence in roseola.

In Epstein-Barr virus infection, rash starts on the trunk and proximal limbs, then spreads to the forearms and face.

Rash primarily affects the face (malar area), arms, and legs in erythema infectiosum (fifth disease).

Rash starts in wrists and ankles, then spreading to the trunk in Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Palms and soles are commonly affected in hand-foot-and-mouth disease, secondary syphilis, Kawasaki disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, rubella, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and toxic shock syndrome.

In mpox virus infection, lesions simultaneously progress through four stages (macular, papular, vesicular, and pustular) before scabbing over and resolving. Lesions are typically 5 to 10 mm in diameter, may be discrete or confluent, and may be few in number or several thousand.[26][50]

Duration of symptoms

The duration of the eruption may be acute (recent onset, <4 weeks), subacute (4-8 weeks), or chronic (>8 weeks). These timeframes are arbitrary.

An acute eruption often has a specific trigger, such as an allergic (e.g., medication) or infectious (e.g., viral) exposure. The distribution of the eruption can be localised or generalised.

Mucous membrane involvement

Mouth: petechial macules on the soft palate (Forscheimer spots) are characteristic of rubella.

Eyes: the conjunctiva and genital mucosa may become painful and inflamed and develop bullous lesions in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN).

Genital area: genital ulcers are associated with secondary syphilis and chikungunya viral infection.

Anorectal: mpox may present with severe/intense anorectal pain, tenesmus, rectal bleeding, or purulent or bloody stools, associated with perianal/rectal lesions and proctitis, pruritus, dyschezia, burning, swelling, and mucus discharge. Anorectal symptoms have been unique to the 2022 global outbreak, and were not described previously.[99][100]

Associated signs and symptoms

Pain is a feature of the rash associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and Kawasaki disease.

Pruritus is a feature of acute graft-versus-host disease. Zika virus infection, chikungunya virus infection, mpox, and dengue fever may cause pruritus.

In mpox virus infection, symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy, headache, backache, and myalgia may appear before or after the rash, or not at all.[26]

Consider serious illness

Several conditions with a serious clinical course may have a maculopapular eruption as a component, and evaluation should be carried out urgently if suspected. Among them are:

Meningococcaemia

Anaphylactic reactions

Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS)

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome and toxic shock syndrome

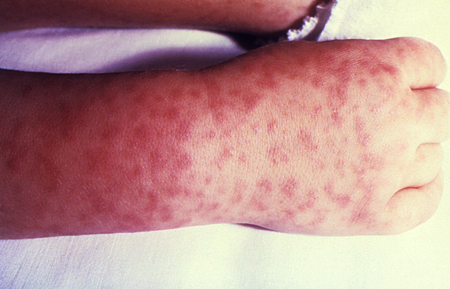

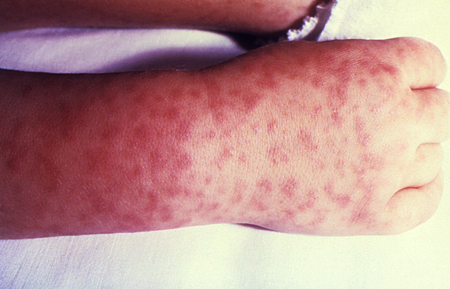

Rickettsial spotted fever.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Characteristic spotted rash of Rocky Mountain spotted feverCourtesy of the CDC Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

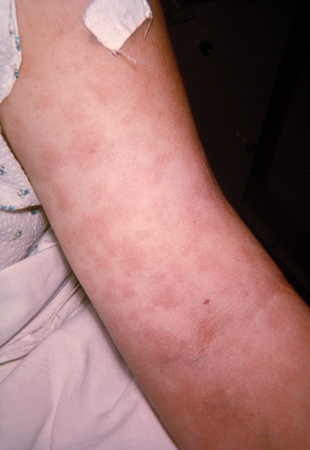

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Morbilliform rash (resembling measles) resulting from toxic shock syndromeCourtesy of the CDC Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Morbilliform rash (resembling measles) resulting from toxic shock syndromeCourtesy of the CDC Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

Ask about:

Fever: may be a feature of viral, bacterial, and rickettsial infections, including sepsis, severe cutaneous drug eruptions, Kawasaki disease, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, adult-onset Still disease, and acute graft-versus-host disease

Headache: may occur in meningitis, toxic shock syndrome, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and viral exanthems

Arthralgia: periodic high fever (often in the late afternoon, spiking in the evening, and resolving) and arthralgias typically precede the eruption in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and adult-onset Still disease.

Drug history

When the clinical presentation is a maculopapular rash, the cause is drug-induced in 50% to 70% of adults and 10% to 20% of children.

A drug reaction is typically suspected when a maculopapular eruption begins within 4 to 12 days of beginning a new medication.

Most reactions develop within 6 to 10 days, though reactions to aminopenicillins may develop over a longer period (>8 days). This interval is the time needed for an immunological (cell-mediated) delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to occur.

The eruption is characteristically polymorphic, usually appearing first on the trunk, then spreading to the limbs and neck.

Moderate pruritus, a low-grade fever, and general malaise may be present.

Mucous membranes are typically spared, and lymphadenopathy is mild if present.

The eruption generally fades over 1 to 2 weeks without complication.

Post-inflammatory desquamation is common and, in the absence of other findings, does not portend a more serious diagnosis such as toxic epidermal necrolysis or staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Death is exceedingly rare.

Antibiotics (sulfonamides, aminopenicillins, cephalosporins) and anticonvulsants are commonly implicated. Chemotherapeutic agents, particularly cytarabine, dacarbazine, hydroxyurea, paclitaxel, and procarbazine, have also been associated with maculopapular eruption.[10] The immunotherapeutic drugs pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and ipilimumab are also associated with maculopapular eruptions.[101] Non-immediate reactions to iodinated contrast media also frequently include maculopapular eruption.[14]

Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors (e.g., cetuximab) also have a propensity to trigger cutaneous eruptions.[12]

In one long-term hospital study of nearly 50,000 patients, drug eruptions presented as maculopapular rash in 91% of cases.[8][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hypersensitivity rash due to penicillinCDC Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Drug eruption due to phenytoinPhotograph courtesy of Brian L. Swick [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Drug eruption due to phenytoinPhotograph courtesy of Brian L. Swick [Citation ends].

Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome are severe generalised eruptions, and are most often drug-induced.[19] Common offending medications include: anticonvulsants, sulfonamides, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and allopurinol. There is widespread cutaneous involvement, with associated involvement of ≥2 mucosal surfaces (oral, conjunctival, anogenital). Skin lesions may be initially targetoid, though often become confluent. Superficial erosion precedes cutaneous necrosis. Patients may develop Nikolsky’s sign, where the epidermal layer sloughs off easily when lateral pressure is applied. Lesions are painful and the patient appears acutely ill.

The presentation of DRESS resembles the maculopapular drug eruption, but the patient is more ill, often with fever, abdominal pain, and facial swelling.[21] In excess of 40 causative drugs have been identified in literature reviews, with antibiotic and anticonvulsant drug classes most commonly implicated.[23][24] Common offending medications include sulfonamides, anticonvulsants (termed anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome), allopurinol, and minocycline.[23][24] The time interval between intake of the offending medication and symptoms is often 2 to 6 weeks.

Exposure to viral agents

Viral exanthems are more common in children and are more likely to have a monomorphic (single form) clinical appearance.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Viral exanthem presenting as a maculopapular eruption. Note urticarial appearance of non-scaling erythematous macules and papules on the trunk of this older childPhotograph courtesy of Hobart W. Walling [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Viral exanthem presenting as a maculopapular eruption. Note the erythematous papules are larger than macules on the leg of a young adultPhotograph courtesy of Hobart W. Walling [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Viral exanthem presenting as a maculopapular eruption. Note the erythematous papules are larger than macules on the leg of a young adultPhotograph courtesy of Hobart W. Walling [Citation ends].

Several findings are characteristic of maculopapular rash associated with viral infection:

May precede, occur simultaneous to, or follow, a viral illness

Presence of fever is common

Recent symptoms of illness, including otitis, pharyngitis, myalgia, arthralgia, dysuria, or gastrointestinal distress, may be elicited

Similar symptoms in close contacts of family members

Pruritus is typically mild.

Social and recreational history

Historical factors to assess in patients with suspected meningococcaemia include living conditions (more common in close living conditions such as college dormitories, prisons), immune status (prior immunisation; people with immunisation >10 years ago, young children, and older people may have inadequate immunity).

Summer/autumn incidence corresponding with outdoor activities and with possible tick exposure is a hallmark of rickettsial disease.[102] Note that approximately half of patients do not recall tick exposure.[70]

Features of rickettsial disease may include:

Fever, with rash beginning on the wrists and ankles as petechial macules and spreading centrally; occasionally maculopapular lesions develop subsequently

Headache, gastrointestinal symptoms, and malaise (common)

Neurological involvement (uncommon).

Examples include Rocky Mountain spotted fever (US, Canada; Central and South America, including Brazil) and Mediterranean spotted fever (Africa, Europe, India, Middle East).[71] Over 30 subtypes have been described.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Characteristic spotted rash of Rocky Mountain spotted feverCourtesy of the CDC Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

Post-transplantation

Acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) is manifest by sudden onset of maculopapular exanthemas in a patient of recent post-transplant status.

This eruption is not uncommon after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplant, and it can appear after blood product transfusion or solid organ transplant. It typically occurs 1 to 3 weeks after transplant

Typically occurs 1 to 3 weeks after transplant.

Periodic fever

Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and adult-onset Still disease are often associated with a maculopapular eruption. Periodic high fever (often in the late afternoon, spiking in the evening, and resolving) and arthralgias typically precede the eruption.[79]

The eruption of the maculopapular rash associated with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis is typically transient (recurring with fever), erythematous, and non-pruritic. The trunk and sites of pressure are favoured.[80]

The maculopapular eruption associated with adult-onset Still disease is salmon-pink, non-pruritic, and accompanies the fever.

The diagnosis may be significantly delayed but is suspected in the context of periodic fevers in the absence of infectious causes, and arthritis.

Clinically unwell patient with systemic illness or sepsis

The possibility of sepsis should be considered because early recognition leads to early treatment, which is associated with significantly improved outcomes in the short- and long-term.[86][87] Maculopapular rash may be a feature in clinically ill patients who have systemic illness or sepsis due to a variety of underlying aetiologies.

A rash may be an early sign in patients with meningococcaemia. It is distinct from the more classic petechial or coalesced purpuric eruption that is frequently found later in the disease process. The maculopapular eruption is transient, lasting for a few to no more than 48 hours, and resembles a wide variety of viral exanthems.

Patient history should include an assessment of living conditions and immune status. Physical examination may find fever and nuchal rigidity. Most patients with meningococcaemia do not have meningococcal meningitis, and often those with meningococcal meningitis do not have meningococcaemia.

Secondary syphilis may present as a maculopapular eruption on the trunk and extremities, and particularly the palms and soles.[103] Rash is of variable appearance, most commonly non-pruritic, and pink to red-brown, ranging from 2-20 mm in diameter. This typically develops some 4-10 weeks after the primary lesion (painless genital ulcer). Rash is often associated with fever and systemic symptoms (e.g., malaise, myalgia, arthralgia, sore throat, and weight loss).[104][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Syphilis presenting with a generalised rashCourtesy of the CDC Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

Three toxin-mediated bacterial infections - scarlet fever, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and toxic shock syndrome - can lead to syndromes of severe clinical illness or sepsis with a generalised maculopapular eruption.[105]

Significant lymphadenopathy, fever, eosinophilia, and hepatic dysfunction may indicate drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS).[22]

Kawasaki disease (mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome) is an acute multi-system febrile disease that primarily affects children aged <5 years.[77] Diagnosis is made clinically, as no specific diagnostic test is available.[77]

Diagnostic criteria include fever for 5 days plus four of the following five signs:[77][78]

Conjunctival injection

Cervical lymphadenopathy, usually unilateral

Oropharyngeal changes (including hyperaemia, oral fissures, cracked lips, and strawberry tongue)

Peripheral extremity changes (including desquamation of hands and feet, erythema, oedema)

Polymorphous rash.

The rash is typically generalised and maculopapular, without petechiae; perineal erythema is particularly pronounced. The rash resembles a viral exanthem, though recognition is critical due to the possibly life-threatening complications of untreated Kawasaki disease:

Cardiac involvement (the most serious complication), including aneurysms in the coronary arteries (the most common cause of death), myocarditis, and coronary heart disease

Multi-organ involvement (common) affecting the central nervous system, eyes, kidney, and gastrointestinal system (including hydrops of the bladder).

Vasculitis of small and medium-sized vessels contributes to the pathology.

Laboratory findings

When a patient presents with a rash suspected to be caused by a drug, no laboratory tests to determine or confirm the responsible drug are readily available.[18] Full blood count may show only mild to moderate peripheral eosinophilia. Metabolic, hepatic and renal function panels are usually normal.

As many serological tests are available, it is impractical to screen every patient with every test. Directed laboratory evaluation is indicated if an infectious aetiology is suspected (based on history and physical examination).

Depending on the particular virus involved, the diagnosis of viral exanthem may be confirmed by viral culture, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), or serology.

The diagnosis of Epstein Barr virus (EBV) is supported by the presence of heterophile antibodies and confirmed with specific EBV antibodies.[106]

PCR testing is available for enterovirus diagnosis but is usually only performed in severe infections.

Rubella diagnosis is confirmed by anti-rubella IgM antibodies or a fourfold rise in anti-rubella IgG titre. Measurement of IgG antibody avidity can be used to distinguish between recent and more distant rubella exposure.[107]

Measles diagnosis is clinical but can be confirmed serologically or by viral culture or PCR.

Diagnosis of erythema infectiosum (fifth disease) is made clinically, with confirmation possible by the finding of anti-B19 IgM antibody.

Where cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is the aetiology of viral exanthem, CMV serology may be positive. PCR and antigen detection are available to aid diagnosis.

Diagnostic testing for meningococcaemia includes isolation of Neisseria meningitidis from a blood culture.

Diagnosis of scarlet fever is suspected clinically and can be confirmed with a rapid streptococcal antigen test, PCR, or throat culture.

The diagnosis of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is generally made clinically. Cultures and Gram stain from skin are typically negative, though Staphylococcus aureus may be cultured from the pharynx, umbilicus, nares, perianal area, or eye. Blister fluid is sterile.

Toxic shock syndrome manifests a characteristic thrombocytopenia with platelet count <100 × 10⁹/L (100 × 10³/microlitre).[60] Toxic shock syndrome toxin may be isolated from serum.[108]

Serological testing confirms the diagnosis of rickettsial disease but does not identify species. A diagnostic rise in titre is generally not seen until the second week of illness. Non-specific laboratory abnormalities include thrombocytopenia and hyponatraemia.

Patients with syphilis screen positive with a serum rapid plasma reagin test and have positive specific treponemal serology (serum T pallidum haemagglutination and serum fluorescent antibody absorption tests). Darkfield microscopy of skin/mucosal exudates and skin biopsy are less commonly performed, but may demonstrate spirochetes.

Marked peripheral eosinophilia and elevated aminotransferases may occur in DRESS.[22][24]

Acute hepatitis serology is positive and aminotransferases are elevated in people with hepatitis B and C. However, serology may be negative in some people with acute hepatitis C infection, and RNA testing should be performed if doubt exists.

Patients with suspected HIV exanthem screen positive for HIV viral RNA or core antigen.

The diagnosis of mpox is confirmed by PCR, which would be positive for monkeypox or orthopoxvirus virus DNA.[109]

Skin biopsy

Before proceeding with a skin biopsy, clinicians should consider whether the information that biopsy may provide justifies the procedure; consultation with a dermatologist is often preferable.

Skin biopsy is an important aspect of the work-up for any patient where aGVHD is suspected. Changes with aGVHD are characteristic, with vacuolar change of the basal layer (grade I), lymphocytic inflammation, and keratinocyte necrosis (grade II), and separation of the dermis and epidermis to form vesicles (grade III) or bullae (grade IV).

Biopsy is optional in the context of a cutaneous drug eruption (non-specific changes) or syphilis (non-specific changes; Warthin-Starry stain may show spirochetes). Biopsy of the skin eruption is generally not indicated in the setting of a viral exanthem.

Skin biopsy in people with suspected staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is indicated only when the diagnosis is not clinically evident. Diagnosis can be confirmed histopathologically, as frozen-section skin biopsy will show an intra-epidermal cleavage.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: During a punch biopsy, local anaesthetic is instilled by injection into the surrounding skin. With the skin stretched perpendicular to normal relaxation lines, a disposable skin biopsy punch with a round stainless steel blade (at least 3 mm or 4 mm in diameter is recommended) is applied perpendicular to the skin. Pressure is applied with a rotating action until a ‘give’ is felt as the blade pierces through the subcutaneous tissue. The cylindrical core of tissue is removed and placed in a labelled sample pot containing a suitable fixative solutionCreated by the BMJ Knowledge Centre [Citation ends].

Drug withdrawal and challenge studies

Guidelines exist for the management of patients with drug eruption.[7][110]

In a patient taking a single medication, withdrawal of the medication when symptoms develop may result in clinical improvement within several days. Unfortunately, the more common clinical scenario involves a patient on multiple medications, and even multiple recently introduced medications.[111]

Ideally, all non-essential drugs are discontinued when symptoms of drug eruption develop. However, as the patient is usually on some medications considered necessary, this may not be straightforward.

Often it is necessary to work with prescribing physicians to determine whether a suspected medication can be stopped and a non-cross-reacting substitute started. Clearly, this introduces several variables and difficulties. In some cases, the risk of discontinuing a critical medication exceeds the risks presented by the eruption, and the causative drug will be continued. Many eruptions will improve regardless, though some may progress to erythroderma.

In vitro testing for migration inhibitions, basophil degranulation, and lymphocyte toxicity may confirm the diagnosis of drug eruption in the presence of a positive test result. However, the test is not widely available, neither is it available for most suspected drugs. Diagnosis with skin-prick testing or patch testing to components of suspected drugs can definitively confirm the diagnosis in some cases.[10][18] One study demonstrated that patch testing in these circumstances has a high specificity but only low sensitivity.[112] Drug challenge studies may also provide a definitive answer but should be done under monitored conditions to avoid anaphylaxis.[113] Oral re-challenge with a suspected causative medication is not generally recommended.[114][115]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer