Treatment of laryngomalacia (LM) should be individualised according to disease severity.[21]Carter J, Rahbar R, Brigger M, et al. International Pediatric ORL Group (IPOG) laryngomalacia consensus recommendations. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016 Jul;86:256-61.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27107728?tool=bestpractice.com

Disease severity does not correlate with the intensity or frequency of stridor, but with the presence of associated symptoms.[7]Roger G, Denoyelle F, Triglia JM, et al. Severe laryngomalacia: surgical indications and results in 115 patients. Laryngoscope. 1995 Oct;105(10):1111-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7564844?tool=bestpractice.com

Most cases are mild, and it is appropriate to adopt a conservative approach with regular review and monitoring of growth using centile charts. If an expectant approach is not appropriate due to the severity, then surgery to address the LM should be considered. Endoscopic surgical treatment is undertaken if the patient becomes compromised by airway obstruction or if feeding is disrupted sufficiently to prevent normal growth. In some patients (e.g., in cases where endoscopic surgery has failed or when there are medical comorbidities), tracheostomy may be necessary. This facilitates bypass of the supraglottic obstruction until spontaneous resolution occurs with growth.

Pressure-assisted ventilation (e.g., bilevel positive airway pressure [BiPAP]) may be used in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) who are not surgical candidates or where surgery has failed to improve airway obstruction. It may also be useful as an interim measure: for example, to enable further surgical procedures to be delayed in the early postoperative period.

Co-existing GORD should be assessed and treated appropriately in all patients, with either changes to feeding techniques, medication, or, in severe cases, surgical intervention. Eosinophilic oesophagitis should be excluded by oesophagoscopy and biopsy in cases with persistent laryngeal oedema contributing to LM.[21]Carter J, Rahbar R, Brigger M, et al. International Pediatric ORL Group (IPOG) laryngomalacia consensus recommendations. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016 Jul;86:256-61.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27107728?tool=bestpractice.com

Research continues to address the relative lack of high-level evidence examining treatments, outcomes, and effects of comorbidities of laryngomalacia.[33]McCaffer C, Blackmore K, Flood LM. Laryngomalacia: is there an evidence base for management? J Laryngol Otol. 2017 Nov;131(11):946-54.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29067893?tool=bestpractice.com

Mild LM

These patients have an audible stridor and endoscopic features of LM, but no respiratory distress and no evidence of failure to thrive (i.e., steady growth on weight centile charts).

Most patients with LM are managed conservatively with observation without surgical intervention. They should be kept under regular review until the condition resolves to ensure the LM is not progressing in severity.

Reflux and minor feeding difficulties should be assessed and treated appropriately. Parents can be reassured that this condition typically resolves spontaneously.

Moderate LM

Moderate disease is associated with stridor, increased work of breathing, progressive feeding difficulties, and either weight loss or inadequate weight gain.

A conservative approach may be taken where the child is kept under observation and regular review to ensure that he or she is developing adequately. Reflux and minor feeding difficulties should be assessed and treated appropriately.

If the child has significant airway obstruction or feeding difficulties affecting growth, then endoscopic supraglottoplasty to modify the supraglottis and relieve the obstruction is appropriate.

Severe LM

Severe disease occurs in 10% to 15% of patients.[34]Valera FC, Tamashiro E, de Araújo MM, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of supraglottoplasty in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome associated with severe laryngomalacia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006 May;132(5):489-93.

http://archotol.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/132/5/489

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16702563?tool=bestpractice.com

[35]Denoyelle F, Mondain M, Grésillon N, et al. Failures and complications of supraglottoplasty in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Oct;129(10):1077-80.

http://archotol.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/129/10/1077

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14568790?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Zalzal GH, Collins WO. Microdebrider-assisted supraglottoplasty. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005 Mar;69(3):305-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15733588?tool=bestpractice.com

These infants may have significant shortness of breath and airway obstruction, failure to thrive, marked dysphagia, associated apnoeas, hypoxia or hypercapnia, pulmonary hypertension, cor pulmonale, delayed neuropsychomotor development, obstructive sleep apnoea, or severe chest deformity (pectus excavatum).

Endoscopic supraglottoplasty is the treatment of choice for all patients with severe disease. Treatment of severe LM underwent a significant change in the 1980s when endoscopic surgery became available as an alternative to tracheostomy or prolonged nasogastric feeding.[35]Denoyelle F, Mondain M, Grésillon N, et al. Failures and complications of supraglottoplasty in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Oct;129(10):1077-80.

http://archotol.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/129/10/1077

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14568790?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Lane RW, Weider DJ, Steinem C, et al. Laryngomalacia. A review and case report of surgical treatment with resolution of pectus excavatum. Arch Otolaryngol. 1984 Aug;110(8):546-51.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6743107?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Seid AB, Park SM, Kearns MJ, et al. Laser division of the aryepiglottic folds for severe laryngomalacia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1985 Nov;10(2):153-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4093254?tool=bestpractice.com

[39]Zalzal GH, Anon JB, Cotton RT. Epiglottoplasty for the treatment of laryngomalacia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1987 Jan-Feb;96(1 Pt 1):72-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3813390?tool=bestpractice.com

Role of surgery

Endoscopic supraglottoplasty (aryepiglottoplasty)

This procedure to modify the supraglottis to relieve obstruction has an excellent success rate, with reports of 79% to 98% of cases having a good outcome.[7]Roger G, Denoyelle F, Triglia JM, et al. Severe laryngomalacia: surgical indications and results in 115 patients. Laryngoscope. 1995 Oct;105(10):1111-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7564844?tool=bestpractice.com

[35]Denoyelle F, Mondain M, Grésillon N, et al. Failures and complications of supraglottoplasty in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Oct;129(10):1077-80.

http://archotol.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/129/10/1077

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14568790?tool=bestpractice.com

Several forms of supraglottoplasty have been described. Surgery is selected according to the observed anatomical features in order to address the main source of supraglottic obstruction. Options include division or excision of the aryepiglottic folds, with removal of redundant supra-arytenoid mucosa, with or without cuneiform or corniculate cartilage if necessary, taking care to preserve the interarytenoid mucosa.[1]Loke D, Ghosh S, Panarese A, et al. Endoscopic division of the ary-epiglottic folds in severe laryngomalacia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001 Jul 30;60(1):59-63.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11434955?tool=bestpractice.com

[40]Senders CW, Navarrete EG. Laser supraglottoplasty for laryngomalacia: are specific anatomical defects more influential than associated anomalies on outcome? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001 Mar;57(3):235-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11223456?tool=bestpractice.com

Alternatively, epiglottopexy may be undertaken, to adhere the epiglottis to the tongue base using a laser, with or without sutures.[3]Werner JA, Lippert BM, Dunne AA, et al. Epiglottopexy for the treatment of severe laryngomalacia. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2002 Oct;259(9):459-64.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12386747?tool=bestpractice.com

Partial amputation of the epiglottis has also been described. Unilateral supraglottoplasty with division of a single aryepiglottic fold is recommended by some authors to minimise the risk of subsequent supraglottic stenosis or aspiration.[41]Reddy DK, Matt BH. Unilateral vs. bilateral supraglottoplasty for severe laryngomalacia in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Jun;127(6):694-9.

http://archotol.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/127/6/694

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11405871?tool=bestpractice.com

[42]Kelly SM, Gray SD. Unilateral endoscopic supraglottoplasty for severe laryngomalacia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995 Dec;121(12):1351-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7488362?tool=bestpractice.com

No difference in outcome has been found using CO₂ laser, laryngeal microscissors, or microdebrider.[7]Roger G, Denoyelle F, Triglia JM, et al. Severe laryngomalacia: surgical indications and results in 115 patients. Laryngoscope. 1995 Oct;105(10):1111-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7564844?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Zalzal GH, Collins WO. Microdebrider-assisted supraglottoplasty. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005 Mar;69(3):305-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15733588?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Lane RW, Weider DJ, Steinem C, et al. Laryngomalacia. A review and case report of surgical treatment with resolution of pectus excavatum. Arch Otolaryngol. 1984 Aug;110(8):546-51.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6743107?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Seid AB, Park SM, Kearns MJ, et al. Laser division of the aryepiglottic folds for severe laryngomalacia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1985 Nov;10(2):153-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4093254?tool=bestpractice.com

[39]Zalzal GH, Anon JB, Cotton RT. Epiglottoplasty for the treatment of laryngomalacia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1987 Jan-Feb;96(1 Pt 1):72-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3813390?tool=bestpractice.com

Repeat procedures may be performed if necessary to address other components of the obstruction. Patients with additional congenital anomalies have poorer outcomes but no higher rate of complications than patients with isolated LM.[35]Denoyelle F, Mondain M, Grésillon N, et al. Failures and complications of supraglottoplasty in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Oct;129(10):1077-80.

http://archotol.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/129/10/1077

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14568790?tool=bestpractice.com

Poor outcomes also occur with widespread pharyngolaryngomalacia, and these patients may require eventual tracheostomy.[7]Roger G, Denoyelle F, Triglia JM, et al. Severe laryngomalacia: surgical indications and results in 115 patients. Laryngoscope. 1995 Oct;105(10):1111-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7564844?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]Froehlich P, Seid AB, Denoyelle F, et al. Discoordinate pharyngolaryngomalacia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1997 Feb 14;39(1):9-18.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9051435?tool=bestpractice.com

Complications occur in less than 8% of cases, and are related to the extent of surgery, amount of tissue excised, and mode of excision.[35]Denoyelle F, Mondain M, Grésillon N, et al. Failures and complications of supraglottoplasty in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Oct;129(10):1077-80.

http://archotol.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/129/10/1077

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14568790?tool=bestpractice.com

Complications include granulomas, synechiae, aspiration, and supraglottic stenosis.[35]Denoyelle F, Mondain M, Grésillon N, et al. Failures and complications of supraglottoplasty in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Oct;129(10):1077-80.

http://archotol.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/129/10/1077

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14568790?tool=bestpractice.com

[42]Kelly SM, Gray SD. Unilateral endoscopic supraglottoplasty for severe laryngomalacia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995 Dec;121(12):1351-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7488362?tool=bestpractice.com

Supraglottic stenosis occurs in 2% to 4% of cases and is difficult to treat.[35]Denoyelle F, Mondain M, Grésillon N, et al. Failures and complications of supraglottoplasty in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Oct;129(10):1077-80.

http://archotol.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/129/10/1077

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14568790?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Reddy DK, Matt BH. Unilateral vs. bilateral supraglottoplasty for severe laryngomalacia in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Jun;127(6):694-9.

http://archotol.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/127/6/694

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11405871?tool=bestpractice.com

Unilateral supraglottoplasty with division of a single aryepiglottic fold has the lowest morbidity, but has the disadvantage of having a higher chance of multiple procedures.[1]Loke D, Ghosh S, Panarese A, et al. Endoscopic division of the ary-epiglottic folds in severe laryngomalacia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001 Jul 30;60(1):59-63.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11434955?tool=bestpractice.com

[35]Denoyelle F, Mondain M, Grésillon N, et al. Failures and complications of supraglottoplasty in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Oct;129(10):1077-80.

http://archotol.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/129/10/1077

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14568790?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Reddy DK, Matt BH. Unilateral vs. bilateral supraglottoplasty for severe laryngomalacia in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Jun;127(6):694-9.

http://archotol.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/127/6/694

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11405871?tool=bestpractice.com

Comorbidities of neurological disorders, syndromes, and congenital heart disease need to be recognised and factored into surgical decision-making. Patients with additional disorders were shown to have an increased risk of aspiration following surgery than those without comorbidities, and delayed post-operative diagnosis of a co-existing neurological disorder has been shown to be significantly associated with surgical failure.[44]Preciado D, Zalzal G. A systematic review of supraglottoplasty outcomes. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012 Aug;138(8):718-21.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22801660?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]Douglas CM, Shafi A, Higgins G, et al. Risk factors for failure of supraglottoplasty. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014 Sep;78(9):1485-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25005226?tool=bestpractice.com

The potential benefits of favourable outcomes versus the risks of complications require careful consideration in these complex cases.

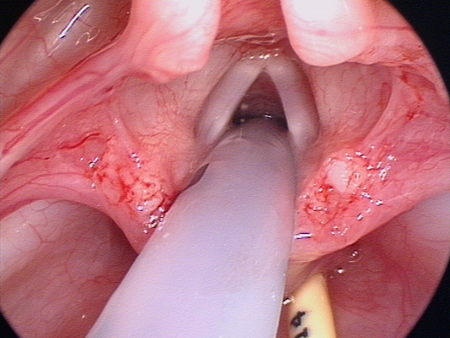

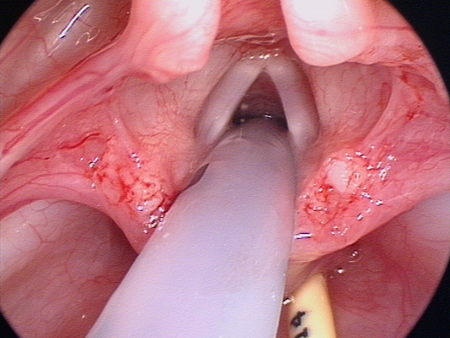

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laryngeal appearance after supraglottoplasty using cold steelFrom the personal teaching collection of Simone J. Boardman, MBBS, FRACS (OHNS) and C. Martin Bailey, BSc, FRCS, FRCSEd [Citation ends].

Tracheostomy

May be necessary in children with severe LM. It serves to bypass the supraglottic obstruction until spontaneous resolution occurs with growth.

It is used in cases where endoscopic surgery has failed or when there are other indications for tracheostomy due to medical comorbidities.

There is substantial potential for short- and long-term morbidity with tracheostomy, including a tracheostomy-related mortality rate of about 2%.[46]Cochrane LA, Bailey CM. Surgical aspects of tracheostomy in children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2006 Sep;7(3):169-74.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16938638?tool=bestpractice.com

Management of GORD

All patients require assessment and treatment of GORD if necessary. Reflux ought to be treated regardless of whether or not surgery is undertaken for the LM. Both conditions are closely related and one may exacerbate the other. Control of reflux may improve the degree of airway obstruction by reducing laryngeal inflammation and oedema.[40]Senders CW, Navarrete EG. Laser supraglottoplasty for laryngomalacia: are specific anatomical defects more influential than associated anomalies on outcome? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001 Mar;57(3):235-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11223456?tool=bestpractice.com

Reflux also often improves significantly with supraglottoplasty due to a decrease in negative intrathoracic and intra-oesophageal pressures.[17]Hadfield PJ, Albert DM, Bailey CM, et al. The effect of aryepiglottoplasty for laryngomalacia on gastro-oesophageal reflux. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003 Jan;67(1):11-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12560143?tool=bestpractice.com

Untreated reflux may delay healing after surgery.[16]Yellon RF, Goldberg H. Update on gastroesophageal reflux disease in pediatric airway disorders. Am J Med. 2001 Dec 3;111(suppl 8A):78S-84S.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11749930?tool=bestpractice.com

Simple treatment options include nursing upright, using bottles to minimise aerophagia, or using thickening feeds. If these conservative measures fail, then options for medical treatment include an H2 antagonist (e.g., famotidine) or a proton-pump inhibitor (e.g., omeprazole). Persistent GORD can be treated surgically with Nissen's fundoplication.