Approach

The diagnosis of laryngomalacia (LM) can often be made on the basis of a typical clinical history and examination findings. This is then confirmed by flexible fibre-optic laryngoscopy at the time of consultation. In many patients, a rigid laryngobronchoscopy (performed under anaesthesia) is also carried out.[21]

Clinical history and examination

Patients typically present with intermittent and variable inspiratory stridor, due to collapse of the supralaryngeal tissue on inspiration. The noise may be worse when the child is active, crying, or feeding, and is more apparent when supine. However, patients typically have a normal cry.

Symptoms typically commence within the first 2 weeks of life and are usually not present at birth. They may progress, becoming more noticeable as the child becomes more active, and are usually maximal by 6 to 8 months of age before gradual, spontaneous resolution by 2 years of age, unless there is a neurological condition contributing to poor laryngeal tone. LM occurs in almost twice as many males as females.[10] The parents may also report noting features of airway obstruction such as suprasternal, sternal, intercostal, or subcostal recession, use of abdominal musculature, or pectus excavatum.

Feeding difficulties occur commonly, with associated poor weight gain, weight loss, or failure to thrive in severe cases. Infants may feed very slowly, often with worsening of the respiratory noise. There may be choking or coughing during the feed, or they may stop feeding to apparently 'come up for air'. Previous episodes of aspiration may have been diagnosed. There may be a past history of episodes of apnoea or cyanosis.

A complete history should be taken, noting any co-existing medical conditions, particularly underlying syndromes or neurological problems. Between 17% and 47% of patients with severe LM have been reported to have additional associated conditions or syndromes.[7][8] These include Down's syndrome and, less commonly, syndromic congenital cardiac disease.[19][20] Neurological-variant laryngomalacia is seen in association with neurological pathology, including generalised or focal hypotonia, and cerebral palsy. These children often exhibit a somewhat atypical form, which does not tend to spontaneously resolve and has been shown to be associated with poorer long-term outcomes following surgical treatment.

On examination, patients have audible inspiratory stridor with features of upper airway obstruction. These include suprasternal, sternal, intercostal, or subcostal recession, and abdominal respiratory effort, but they typically seem comfortable and are not in acute respiratory distress despite their noisy breathing. Pectus excavatum may be present. The general appearance, including any syndromic features, should be noted. The child's weight should be plotted on appropriate growth centile charts.

Flexible laryngoscopy

Flexible laryngoscopy should be performed at initial examination to assess laryngeal anatomy and related comorbidity (e.g., mucosal inflammation as evidence of GORD). The presence of dynamic supralaryngeal collapse during the inspiratory phase of respiration confirms the diagnosis. Topical anaesthesia is applied to the nasal mucosa so the upper airway and larynx may be examined while the child is fully awake. This allows assessment of vocal cord movement. However, flexible laryngoscopy does not provide for a reliable assessment of the subglottis or more distal airway.

The collapse becomes more marked if the child is crying or agitated during the endoscopy. There may be narrowing of the glottic airway from indrawing of the arytenoids or aryepiglottic folds, including the mucosa, cuneiform, or corniculate cartilages. The epiglottis may be curled and angled posteriorly and the aryepiglottic folds may be shortened (15% of cases).[22][11] Redundant mucosa on the lateral aspect of the epiglottis may collapse into the glottis on inspiration. These features may occur simultaneously or in any combination. There is normal symmetrical vocal cord movement, provided there is no coexisting vocal cord palsy. More widespread collapse has been described with involvement of the entire pharyngolarynx.

Rigid laryngobronchoscopy

With flexible laryngoscopy, subglottic views cannot be reliably obtained to exclude synchronous airway pathology. LM can only be confirmed with dynamic views obtained during spontaneous respiration, under a general anaesthetic, usually as the general anaesthesia lightens. The use of rigid laryngobronchoscopy can both confirm the findings of flexible laryngoscopy and reliably exclude co-existing airway lesions.

The incidence of second lesions has been reported to be between 12% and 64%.[22][8][23][24][25] This wide variation may reflect a higher incidence of second airway lesions in the patient population attending tertiary referral centres that manage complex paediatric airway pathology.

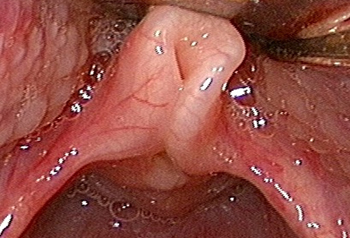

There is some controversy as to whether rigid endoscopy is required in every case. Some authors advise a full airway assessment in all patients with LM to ensure potentially life-threatening pathology is not overlooked, whereas others proceed with rigid endoscopy only if there is apnoea, failure to thrive, or clinical suspicion of a second lesion.[22][24][26] The procedure is performed in all cases requiring endoscopic surgery for treatment of LM.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Typical example of laryngomalaciaFrom the personal teaching collection of Simone J. Boardman, MBBS, FRACS (OHNS) and C. Martin Bailey, BSc, FRCS, FRCSEd [Citation ends].

Other investigations

Videofluoroscopic swallowing studies or functional endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) testing is used to assess feeding problems to detect episodes of laryngeal penetration or aspiration.

Investigations to document GORD should also be performed. The diagnosis of GORD may be suggested by the clinical history or by laryngeal appearance on endoscopy. A rigid oesophagoscopy with biopsies may be performed. Other options include 24 hour pH monitoring and/or barium swallow.

Polysomnography (PSG) sleep studies are conducted to determine whether there is associated obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA).[27] This test can provide useful information, particularly in following the progress and making management decisions for complex patients with multiple medical problems. This may be particularly relevant in children who experience a poor outcome after supraglottoplasty. Sleep studies are not useful in the diagnosis of LM but may assist in the ongoing management of these patients.

Radiological tests are not required in the diagnosis of LM, although the dynamic supralaryngeal collapse may be seen on fluoroscopy. Airway fluoroscopy has been found to be highly specific in diagnosing LM, tracheomalacia, and airway stenosis; however, its sensitivity is poor and, therefore, its role as a screening tool is uncertain.[28] Chest x-ray and lateral airway views may also provide evidence of synchronous airway pathology or aspiration. In patients with clinical findings suggestive of an underlying genetic syndrome associated with congenital heart disease (e.g., Down's syndrome), evaluation with ECG and echocardiogram should be performed.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer