Approach

The assessment of gait abnormalities is essentially clinical. With knowledge of normal gait and developmental milestones, the history and physical examination, along with judicious use of investigations, can often provide an accurate diagnosis. The child will not necessarily vocalise any pain, and the absence of pain does not exclude a significant cause of limping or gait disturbance.

Growth charts, including height and weight, are also important; trends should be assessed where possible, as failure to gain weight or heights, and crossing centile lines, should always raise a concern about chronic pathology.

The child should be examined comprehensively, barefoot and with legs exposed, to ensure the whole limb is assessed. Musculoskeletal examination should follow a ‘look, feel, move, function’ approach and all joints should be examined. The pGALS (paediatric Gait, Arms, Legs, Spine) approach to examination has been validated in school-age children and comprises a series of simple manoeuvres to look at joint movement and detect areas of abnormality that require a more detailed examination.[28] pGALS (paediatric Gait Arms Legs and Spine): a simple examination of the musculoskeletal system in school-aged children. Opens in new window pGALS (paediatric Gait Arms Legs and Spine) app: a free resource available from app stores Opens in new window Paediatric Musculoskeletal Matters (PMM): an e-resource to aid teaching and learning about the essentials of paediatric musculoskeletal medicine Opens in new window Arthritis Research UK: clinical assessment of the musculoskeletal system Opens in new window

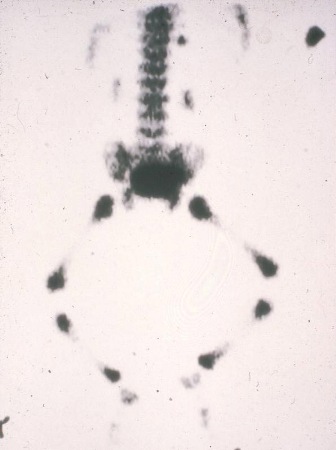

With normal variants, investigation is required if changes are progressive, non-resolving beyond the expected ages, asymmetric or painful; if they cause a functional limitation, a regression or delayed gross motor milestones; or if other abnormalities are observed on musculoskeletal or neurological examination. Investigations may include full blood count/film, acute phase reactants, infection screen, and imaging (x-rays, ultrasound and MRI). Bone scan is rarely indicated in the assessment of acute limp, but may be considered in the assessment of suspected benign or malignant bone cancer.[29][30]

History

Age and developmental history

Age at onset of symptoms is helpful in considering the differential diagnoses of limp. For example, transient synovitis (toxic synovitis, irritable hip) and Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease are more likely in the young school-age child compared with the older child and adolescent, when slipped capital femoral epiphysis is more prevalent. Enquiry about developmental milestones is important.

Walking delay beyond 18 months always warrants investigation, particularly in boys, to exclude neuromuscular diseases (inherited myopathies), as does global delay with speech, hearing, vision, and fine motor milestones (feeding, continence, learning disabilities, and motor asymmetry including hand preference before 18 months of age). Delay may suggest the presence of neurological disorders such as cerebral palsy.

Visual impairment can present with abnormal gait and/or delay in both gross and fine motor development, so it is important to ask the parents and/or child about vision.

Delay and evidence of multi-system involvement warrants consideration of metabolic causes (osteomalacia and lysosomal storage disease).

Regression of motor milestones is always significant. Inflammatory arthritis (i.e., JIA), inflammatory myopathies (e.g., juvenile dermatomyositis), and neurodegenerative disorders need to be considered.

Site of pain, duration, and periodicity

Children with new-onset gait abnormality should be referred for further assessment.[31] Acute onset and persistent pain/limp suggests trauma or serious causes such as infection.

Unwitnessed trauma is common in very young children. Toddler's fracture (non-displaced spiral fracture of the tibia) needs to be considered in apparently well but non-weight-bearing young children.

Overuse injuries (stress fractures, avulsion fractures) may be subacute or acute and are more common in active children.

Periodic symptoms that increase with or after exercise suggest mechanical problems and may present during periods of fast growth, such as early adolescence. It may be useful to enquire about locking or giving way, or pain with certain movements.

Diurnal variation, with symptoms often worse in the mornings or after periods of rest (gelling), suggests inflammatory causes, and may be chronic for some time before presentation, but the child may have adapted their activities to account for this.

Pain may be either not localised or non-vocalised in the young child and is not a good discriminator for JIA.[7] Parents may observe alternatively that the young child presenting with JIA is more irritable, sleeps less well, and is less keen to walk (regression of motor milestones). Referred pain (especially spine or hip disease manifesting as thigh and knee pain) must always be considered, especially in young children who may have difficulties localising problems.

Referred pain (especially spine or hip disease manifesting as thigh and knee pain) must always be considered, especially in young children who may have difficulties localising problems.

Relieving factors

Night pain responsive to NSAIDs is characteristic of osteoid osteoma.[32]

Postures that alleviate pain are helpful for diagnosis. Children with an transient synovitis of the hip usually adopt a position of hip flexion, external rotation, and slight abduction.

Presence of 'red flags'

Systemic upset (e.g., fever, chills, weight loss, night pain) always necessitate consideration of infection or malignancy.

Inconsistent history and incongruent injuries should raise suspicion of non-accidental injury.

Functional limitations

Limitation of activities always warrants concern.

Marked functional limitation despite few physical signs may suggest pain amplification; a full psychosocial history may be useful.

Pregnancy and perinatal history

It is important to enquire about the pregnancy and any prematurity or delivery problems (increasing risk of perinatal hypoxia and injury to the developing brain).

Family history

It is important to enquire about any family history of auto-immune diseases (inflammatory arthritis, psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, thyroid disease, diabetes), neuromuscular disease (muscular dystrophies, peripheral neuropathies), haematological disease (haemoglobinopathies, haemophilia), metabolic diseases (osteomalacia and chronic renal disease, lysosomal storage diseases), immunodeficiency, or skeletal dysplasias.

Past medical history

Inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis are associated with inflammatory arthritis.

Non-accidental injury should be considered in the context of frequent hospital visits and injuries.

Immunodeficiency syndromes may be suggested by previous/recurrent infections, especially invasive bacterial infections.

Renal problems or malabsorption syndromes such as coeliac disease or Crohn's disease may predispose to rickets.

Early feeding difficulties and developmental delay may be suggestive of cerebral palsy.

Ethnicity

The risk of osteomalacia is higher in children of Asian families with poor sun exposure and dietary vitamin D deficiency.

Sickle cell disease is common in children of central African origin and may be present in children of Mediterranean and western Asian origin.

Social history

Evaluation of home and school life may identify triggers for pain amplification, such as bullying, parental separation or family illness.

Deprivation and poverty increase the risk of TB.

Sporting activities may point to specific injuries (e.g., repetitive use or twisting).

Travel history

History of recent travel abroad may be relevant for acute monoarthritis, Lyme disease (there may also be history of a tick bite or rash) and reactive arthritis (following a GI infection, Shigella, Yersinia, Campylobacter species)

Travel history of family members may be relevant for TB.

Systematic factors

Recent sore throat, chest infection and upper respiratory tract infection may precede symptoms of an irritable hip (characteristically following an interval of 10 to 14 days after the infectious episode). Gastrointestinal upset (possibly following foreign travel) may pre-date reactive arthritis.

Sexual history (including contacts and symptoms of dysuria and discharge) may be relevant in the older child/adolescent with a presentation suggestive of reactive arthritis; for example, arthritis, conjunctivitis, dysuria.

Rashes such as psoriasis may associate with psoriatic arthritis (a sub-type of JIA). A photosensitive rash on the face or eyelids is suggestive of juvenile dermatomyositis in the context of muscle weakness. Photosensitive rash in the presence of arthralgia and malaise, especially in an adolescent girl may indicate systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) but is less likely to present with limp. A maculopapular rash, often occurring at times of high fever, is characteristic of systemic-onset JIA.

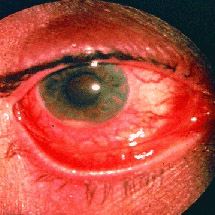

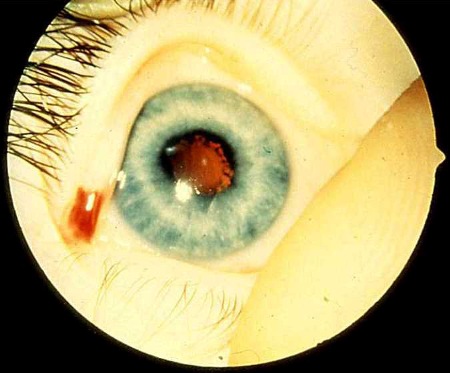

Prior history of red eye is typical of acute anterior uveitis in HLA-B27-associated arthritis in children (usually enthesitis-related sub-type of JIA). The presence of visual blurring indicates chronic anterior uveitis and has a worse prognosis. Red eye and pain are usually absent in chronic anterior uveitis.

Physical examination

General examination

Temperature. High temperature may be suggestive of sepsis.

General appearance. Pallor may indicate anaemia.

Lymph nodes. Lymphadenopathy suggests sepsis or malignancy.

Growth. Poor growth suggests chronic disease.

Measurement of head circumference is an important aspect of the general examination, particularly where there are concerns about development or a neurological cause for presentation.

Skin changes. Rashes are a common feature in psoriasis, juvenile dermatomyositis and systemic-onset JIA; calcinosis is seen in juvenile dermatomyositis; nodules in JIA and rheumatoid factor-positive polyarticular sub-type; and redness and erythema in sepsis. Nailfold capillary loop dilatation is a feature of skin involvement in juvenile dermatomyositis. Bruises, finger marks, scratches, and burns may be suggestive of non-accidental injury.

Dysmorphic features are signs of congenital and metabolic syndromes. Hairy patch, naevus, sinus opening, midline lipoma or haemangioma at base of spine can be seen in spina bifida. Hemi-hypertrophy can be observed.

Feet should be examined to look for local causes of limp (verrucae, trauma, blisters and calluses from ill-fitting shoes).

Ears, nose, and throat can be possible sources of sepsis.

Cardiovascular and respiratory systems should be examined as a possible source of sepsis.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Juvenile psoriatic arthritis with skin changesFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Juvenile dermatomyositis: Gottron's skin changes over the kneesFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Juvenile dermatomyositis: Gottron's skin changes over the kneesFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis rashFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis rashFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Calcinosis in juvenile dermatomyositisFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Calcinosis in juvenile dermatomyositisFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Erythema, redness and swelling in septic arthritis of the shoulderFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Erythema, redness and swelling in septic arthritis of the shoulderFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Nailfold capillary loop dilatation in juvenile dermatomyositisFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Nailfold capillary loop dilatation in juvenile dermatomyositisFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

Musculoskeletal examination

The general approach of ‘look, feel, move, function’ should be adopted. An initial approach of looking at all joints using an examination approach such as pGALS is recommended.[28]

Evidence of bone tenderness or soft-tissue swelling/bruising should be sought. Consider trauma fracture and malignancy with bone tenderness with or without soft-tissue swelling.

Consider symmetry of joint appearance, joint range of movement, hypermobility, muscle wasting and muscle bulk, and leg length discrepancy.

Consider spine appearance (e.g., hairy naevus, scoliosis, myelomeningocele), kyphosis and scoliosis.

Use Trendelenberg's test for weak hip abductors (consider hip pathology).

Consider referred pain (especially spine/hip disease manifesting as thigh and knee pain).

Where developmental dysplasia of the hips is suspected in babies, Barlow's and Ortolani's manoeuvres can be used.[33][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: pGALS (paediatric Gait, Arms, Legs, Spine): a musculoskeletal screening assessment for school-aged children [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hypermobility of the fingersFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hypermobility of the fingersFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

Neurological examination

Consider muscle bulk and symmetry, motor strength, tone, and reflexes.

Observation of the posture and movements of the child while comfortable and/or playing provides a lot of useful information.

Evidence of muscle wasting should prompt the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathies (Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome). Pseudo-hypertrophy is typical of Duchenne's/Becker's dystrophies.

Persistent primitive reflexes may raise suspicion of neurological disease (e.g., cerebral palsy).

The Gower's test for proximal weakness (muscle dystrophies, hip disease) involves asking the child to get up unaided from a sitting position on the floor and observing for evidence of difficulty. An abnormal Gower's test can often be predicted in a child over 5 years of age who is not able to jump.

Use straight leg raise for sciatic nerve root symptoms.

Tandem walk (heel-to-toe walking) is a useful test for identifying ataxic gait.[34]

Developmental examination

Gross motor, vision, and fine motor skills should be evaluated in the context of normal developmental milestones. Asymmetry in both arms and legs should be evaluated.

Handedness before the age of 18 months is abnormal.[35]

Simple screening tests for gross motor skills include walking on the lateral aspects of the feet or standing on one leg, hopping, skipping, and kicking a ball, or heel-toe walking. Stacking blocks or threading beads is a useful screening test for hand-eye coordination.

Vision can be grossly assessed through observing how well the child identifies and reaches for small items, or in literate children by asking them to read words from a book. If concerns about vision have been elicited from the history or examination, this needs to be formally assessed.

Abdominal examination

Evidence of localised tenderness, masses and organomegaly should raise the suspicion of malignancy.

Referred pain to the thigh/groin and abnormal gait may suggest appendicitis or a psoas abscess.

Investigations

Most children presenting with abnormal gait will require a laboratory evaluation (directed by the history and physical examination findings) and a radiological evaluation. Other tests such as muscle biopsy or genetic studies may be helpful in special circumstances.

Blood tests

FBC with differential to evaluate leukocytosis (sepsis), anaemia (chronic disease), electrophoresis (haemoglobinopathies), and blood film if leukaemia or malignancy is suspected.

Acute phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) are elevated in sepsis and inflammatory conditions, but are non-specific. However, in many cases of JIA, the acute phase reactants levels are normal.

Infection screen

Cultures of blood, urine and stool should be considered (especially if there is suspicion of reactive arthritis from recent travel or sexual history).

Serology for Yersinia or Campylobacter infection is indicated if the child has a history of gastroenteritis. Lyme serology should be performed if there is a history of travel to an endemic area (with or without the typical history of rash or tick bite). Throat swab and antistreptolysin O titre (ASOT) should be carried out for streptococcal infection. Chlamydia serology is indicated if there is concern about sexually acquired reactive arthritis.

Bone chemistry

Raised alkaline phosphatase, low or normal calcium or 1,25-OH vitamin D, and raised phosphate are suggestive of osteomalacia.

Raised phosphate is suggestive of rickets (consider also hypophosphataemic rickets).

Auto-antibodies: antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and rheumatoid factor (RF) are not diagnostic of JIA but are useful prognostic indicators. Children with JIA and a positive ANA are at higher risk of chronic anterior uveitis; those with JIA and a positive RF are more likely to have aggressive joint disease, albeit with low risk of uveitis.

Other positive auto-antibodies (double stranded DNA, extractable nuclear antigen [ENA]) are indicative of connective tissue diseases (such as SLE), although this is less likely to present as gait disturbance in children and adolescents.

Muscle enzymes

Muscle dystrophies should be considered in the child with delayed walking, especially boys, and a high creatine kinase should warrant urgent referral.

Muscle enzymes may also be raised in inflammatory muscle disease.

Coagulation screen

Prothrombin and clotting times, and clotting factor should be evaluated if haemophilia is suspected in the presence of: easy bruising, haemarthrosis, soft-tissue/muscle haematomas in a toddler, family history of bleeding disorders, or bleeding after dental procedures.

X-rays

Indicated in the context of suspected trauma, orthopaedic hip conditions and non-accidental injury.

Films of long bones should include anterior posterior (AP) and lateral views of shaft and joints at both ends, and views of both sides of the bone to allow comparison with the healthy side.

Hip x-rays need to include AP and frog views (to exclude slipped capital femoral epiphysis).

With unwitnessed trauma and in the non-weight-bearing young child, toddler's fracture (non-displaced spiral fracture of the tibia) is common. Oblique x-rays may be helpful, although they may be normal initially. If toddler's fracture is indicated, immobilisation in a long leg cast and repeat x-rays at 10 to 14 days usually confirms a healing fracture.

A skeletal survey may be useful in the evaluation of skeletal dysplasia or non-accidental injury. Local policies should be followed. It should be reviewed by an expert radiologist to distinguish changes from normal variants.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Non-accidental injury with 'hot spots' on bone scan due to multiple fracturesFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

CT and MRI

CT is of limited use due to radiation exposure and the need for sedation in young children. However, CT imaging may help to localise and delineate osteoid osteomas and may be useful in the assessment of certain bony pathologies.

MRI remains the diagnostic standard for assessment of detailed bone and joint anatomy and to evaluate joints for synovitis and effusion, and muscles for inflammatory myopathies. It can be challenging to perform an MRI in young children, due to the requirement to lie still.

Ultrasound

Well tolerated and sensitive when used to detect joint effusion, especially at the hip.

In suspected non-accidental injury in very young children, ultrasound is useful to investigate areas where ossification is normally delayed (such as capital femoral epiphysis and proximal and distal humerus).[36]

EMG and/or muscle biopsy

Indicated if muscle diseases (inherited or inflammatory myopathies) or nerve diseases are suspected.

Bone biopsy

Bone and bone marrow biopsies may be indicated in the diagnostic work-up for malignancy.

Genetic studies

May be needed to confirm the presence of inherited myopathies, peripheral neuropathies and chromosomal disorders. HLA-B27 is associated with sub-types of JIA (enthesitis-related arthritis) and acute anterior uveitis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Acute anterior uveitis in HLA-B27-associated juvenile idiopathic arthritis, showing red injected eye and hypopyon (inflammatory exudates in anterior chamber)From Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

Nailfold capillaroscopy

Should be performed if connective tissue disorder is suspected. The presence of dilated nailfold capillary loops is a feature of vasculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Nailfold capillary loop dilatation in juvenile dermatomyositisFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

Slit lamp examination

Mandatory screening test if JIA is suspected since chronic anterior uveitis is usually asymptomatic in the early stages, and does not cause a red eye or pain.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chronic anterior uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: irregular pupilFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chronic anterior uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: cataractFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chronic anterior uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: cataractFrom Dr Foster's personal collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

Other tests

Specific urine tests are recommended if considering certain metabolic conditions as a cause for abnormal gait. These tests are associated with false-positive and false-negative results. Testing more than one urine sample is recommended.

Further specific enzyme assays require a blood sample, and a specialist referral is recommended in children with joint abnormalities (such as hypo-mobility) and no inflammatory arthritis.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer