Aetiology

The cause of asbestosis and asbestos-related pleural changes is the inhalation of asbestos fibres. Asbestos is a fibrous silicate, which exists as a naturally occurring mineral. Chrysotile is the primary asbestos mined. The other 5 types of asbestos that are mined commercially are known as amphiboles and include actinolite, amosite, anthophyllite, crocidolite, and tremolite.[8] Tremolite is also typically a contaminant of chrysotile.

Airborne asbestos particles <10 microns can be inhaled. The more asbestos inhaled the greater the risk of developing asbestosis. The minimum amount required to cause asbestosis is unknown, but a level of 10 fibre/mL-years is a reasonable estimate.[9] The first legal standard in the US in 1971 was 5 fibres/mL; voluntary standards prior to that allowed up to 30 fibres/mL. Asbestos-related pleural changes can occur at appreciably lower levels than those needed to cause asbestosis.

There is no difference in the risk of asbestosis or pleural-related changes by mineral type of asbestos.[10]

Pathophysiology

When asbestos fibres are inhaled, they deposit at alveolar duct bifurcations and cause an alveolar macrophage alveolitis. These activated macrophages release cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor and interleukin-1beta and oxidant species, which initiate a process of fibrosis.[4] The initial interstitial fibrosis typically occurs in the lower lobes and may progress to extensive fibrosis and honeycombing. Peri-bronchial fibrosis with a cellular infiltrate may narrow the airway and cause reduced air flow.[4]

The presence of asbestos bodies, coating of asbestos fibres that are typically amphiboles not chrysotile with iron and haemosiderin, are useful diagnostically but are rare (<15% with asbestosis).[11]

The presence of asbestos fibres is associated with radiographical changes.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Posterior-anterior view of the chest with bibasilar linear interstitial changes consistent with asbestosisFrom the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman MD [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Posterior-anterior view of the chest with 'en face' pleural changes in the mid zones on the right and left (arrows)From the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman MD [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Posterior-anterior view of the chest with 'en face' pleural changes in the mid zones on the right and left (arrows)From the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman MD [Citation ends]. However, since the most common asbestos fibre, chrysotile, is more easily broken down and cleared from the lung than amphibole fibres, the correlation is with the amphibole fibres, such as tremolite, that contaminate the chrysotile.[8]

However, since the most common asbestos fibre, chrysotile, is more easily broken down and cleared from the lung than amphibole fibres, the correlation is with the amphibole fibres, such as tremolite, that contaminate the chrysotile.[8]

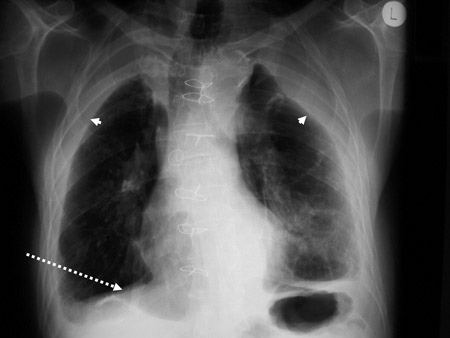

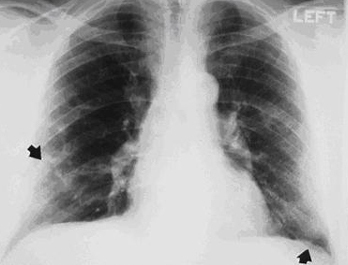

The mechanism of asbestos fibre clearance is partially through lymphatic drainage and the pleural cavities. Mechanical irritation and inflammation is the presumed initiating mechanism for the pleural scarring. Typically, few fibres are found in pleural plaques. When present, the fibres are preferentially chrysotile.[12] The plaques usually occur on the parietal pleura and are acellular collagen that may calcify. When the plaques are found on the visceral pleura, they may extend into an interlobar fissure. Individuals who develop a benign pleural effusion are likely to go on to have diffuse pleural thickening, which involves the visceral pleura.[1][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Diffuse pleural thickening (arrowheads) and elevated left hemidiaphragm (dotted arrow)BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0253 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Posterior-anterior view of the chest with 'mesa'-like pleural thickening of the left diaphragm and 'in-profile' pleural thickening of the mid zones of both the left and right lungsFrom the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman MD [Citation ends].

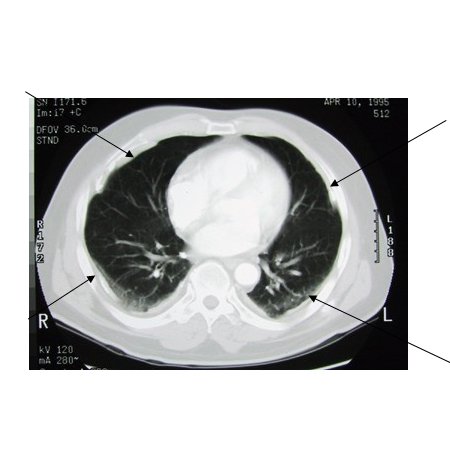

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Posterior-anterior view of the chest with 'mesa'-like pleural thickening of the left diaphragm and 'in-profile' pleural thickening of the mid zones of both the left and right lungsFrom the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman MD [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the chest showing multiple examples of pleural thickening most with calcification (arrows)From the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman MD [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the chest showing multiple examples of pleural thickening most with calcification (arrows)From the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman MD [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan confirming symmetrical thickening (arrowheads) with a calcified pleural plaque (broken arrow, top right) and an area of rounded atelectasis (Blesovsky's sign; dotted arrow, bottom right)Adapted from BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0253 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan confirming symmetrical thickening (arrowheads) with a calcified pleural plaque (broken arrow, top right) and an area of rounded atelectasis (Blesovsky's sign; dotted arrow, bottom right)Adapted from BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0253 [Citation ends]. Diffuse pleural thickening may also occur from confluence of smaller parietal pleural plaques or extension of subpleural interstitial fibrosis. Rounded atelectasis from both parietal and visceral pleural scarring and partial collapse of adjoining lung tissue can mistakenly appear as a tumour on a chest x-ray.[8]

Diffuse pleural thickening may also occur from confluence of smaller parietal pleural plaques or extension of subpleural interstitial fibrosis. Rounded atelectasis from both parietal and visceral pleural scarring and partial collapse of adjoining lung tissue can mistakenly appear as a tumour on a chest x-ray.[8]

Classification

Asbestosis is a type of pneumoconiosis. These are chronic lung diseases caused by exposure to a mineral dust or metal. The most common pneumoconioses are asbestosis, silicosis, coal workers' pneumoconiosis (black lung disease), and chronic beryllium disease. A history of exposure will usually reveal the causative agent. The International Classification of Radiographs for Pneumoconiosis, developed by the International Labour Organization (ILO), is used to report chest x-ray findings.[3] For more detail on the ILO classification, see Diagnostic criteria.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer