Approach

History and physical examination followed by chest x-ray can narrow the differential of pleuritis. Further tests can be ordered depending on the clinical suspicion. It is important to evaluate and exclude potentially life-threatening conditions such as pulmonary embolism, acute coronary syndrome, aortic dissection, and pneumothorax during evaluation. Pneumonia must also be considered.

History

Important points to be noted include the following.

Symptom onset: can give clues to aetiology.

Acute onset indicates myocardial infarction (MI), pulmonary embolism, or pneumothorax. History should be evaluated for prior venous thromboembolism. Presence of malignancy or hypercoagulable states increases the risk of pulmonary embolism. The modified Wells criteria should be used for risk stratification. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Modified Wells criteria (score ≤4: PE unlikely; score >4: PE likely)From Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83:416. Used with permission [Citation ends].

Subacute onset over hours to days suggests infection or inflammatory causes.

Chronic pain over weeks may indicate malignancy or tuberculosis (TB).

Radiation of pain: to back, shoulder, arms, or jaw raises suspicion for aortic dissection, or MI.

Prodromes: viral prodrome, fever, sputum production, and sick contacts suggest an infectious aetiology.

Drug history: recent initiation of a new drug can cause pleural inflammation.

Exposures: history of exposure to asbestos should be sought.[18] A thorough occupational history should be taken. Asbestos exposure may occur in occupations requiring work on brake and clutch linings, in construction or demolition work, or in dock and shipyard work. Electricians, plumbers, and launderers are also at risk. It is important to consider if there may have been para-occupational exposure (e.g., indirect contact via another close contact, household member, or spouse whose occupation involves direct contact with asbestos).[44]

Autoimmune features: suggested by the presence of other signs and symptoms such as malar rash in systemic lupus erythematosus, joint pain in rheumatoid arthritis, or dry mouth and eyes in Sjogren syndrome.

Physical examination

Hypotension, hypertension, and hypoxaemia are red flags that need urgent evaluation for pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, and MI. Other important points in the examination include:

Pulsus paradoxus is a sign of pericardial effusion and tamponade

A pericardial friction rub is heard in pericarditis

Unequal pulse and BP between arms is suggestive of aortic dissection

Decreased breath sounds with increased resonance on percussion suggests pneumothorax

Decreased breath sounds with dullness to percussion is suggestive of pleural effusion.

Laboratory evaluation

Laboratory tests depend on clinical indications.

Full blood count (FBC) is useful to evaluate for elevated white blood cell (WBC) count when an infectious aetiology is suspected (e.g., systemically ill patient, fever, tachycardia).

C-reactive protein may be elevated in the presence of infection, inflammation, or malignancy and should be ordered when these diagnoses are being considered.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and serologies for autoimmune disorders such as antinuclear antibody and rheumatoid factor should be ordered when connective tissue diseases suspected (e.g., history of connective tissue disease, arthritis, joint deformities, rash, alopecia, dry eyes, or mouth).

Blood cultures may help isolate the offending organism in the case of an infectious aetiology such as bacterial pneumonia.

Sputum cultures may help isolate the offending organism in suspected bacterial pneumonia or TB. Sputum smear may be positive for acid-fast bacilli if TB is present and is considered an initial diagnostic test in the relevant clinical setting. Ideally, three deep-cough, spontaneously produced sputum samples should be sent for diagnosis of TB. One should be an early morning sample.[45]

D-dimer test using highly sensitive assay can be useful to rule out pulmonary embolism in cases of low pre-test probability.

Cardiac enzymes including creatine phosphokinase, LDH, and troponins are ordered if there is suspicion of cardiac aetiology of chest pain (e.g., substernal chest pain radiating to left arm, neck, or jaw).

Measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-pro-BNP) may be considered to supplement assessment of global risk in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome.[26]

Imaging studies

Chest x-ray is an essential initial imaging test to evaluate for pleural thickening, effusions, pulmonary infiltrate, or pneumothorax.

Chest x-ray can be abnormal in up to 84% of patients with pulmonary embolism but the findings such as atelectasis, parenchymal abnormalities, and effusion are non-specific.[46]

Chest x-ray may also be used as an initial investigation when evaluating acute coronary syndrome or aortic dissection.

Computed tomography (CT) pulmonary angiography or ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scan is indicated if pulmonary embolism is suspected (e.g., sudden-onset chest pain, history of prolonged immobility, hypercoagulable syndromes).

Doppler ultrasound of the lower extremity may be used to exclude a deep vein thrombosis above the popliteal fossa associated with pulmonary embolism.

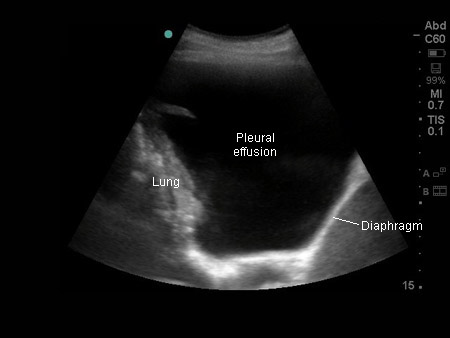

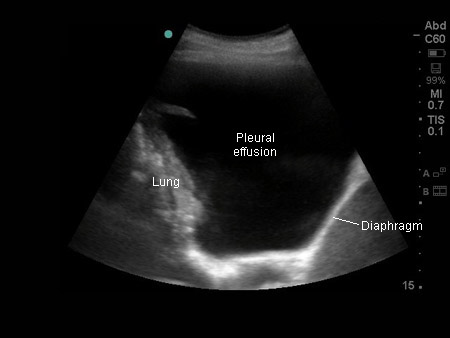

Thoracic ultrasound scan is indicated following chest x-ray to confirm the presence of a pleural effusion and assess for loculations, pleural thickening, or nodules. Ultrasound is also recommended to mark a suitable site for thoracocentesis or chest drain insertion.

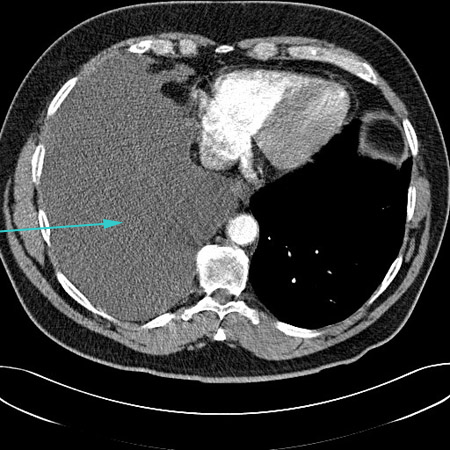

CT scan chest may be indicated to assess characteristics of effusions seen on plain chest x-ray (e.g., assess for loculation, pleural rind, empyema). CT may also be used to confirm the diagnosis of pneumothorax if diagnostic uncertainty, as well as diagnosis of mesothelioma and non-mesothelioma malignancy.

CT chest with contrast should be ordered as soon as diagnosis of aortic dissection suspected (e.g., acute substernal tearing sensation, with radiation to interscapular region of the back, unequal pulses or BPs in both arms, widened mediastinum on chest x-ray).

Urgent coronary angiography should be considered for patients with acute coronary syndrome demonstrated on ECG.

Transoesophageal echocardiography can be ordered as a supplementary test in stable patients when acute proximal aortic dissection is suspected, or if CT is unavailable.

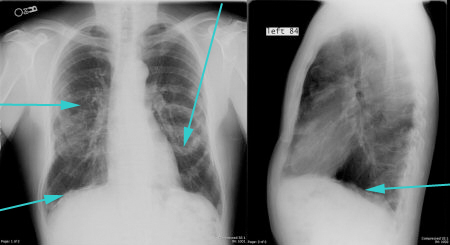

MRI angiography, although accurate, is rarely indicated in the acute setting of aortic dissection because it is difficult to obtain.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: PA and lateral CXR showing calcified pleural plaquesFrom the collection of Dr Ami Rubinowitz; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CXR showing large right pleural effusionFrom the collection of Dr Kathryn Bateman; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CXR showing large right pleural effusionFrom the collection of Dr Kathryn Bateman; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Thoracic ultrasound image of large, simple pleural effusionFrom the collection of Dr Nicholas Maskell; used with permission [Citation ends].

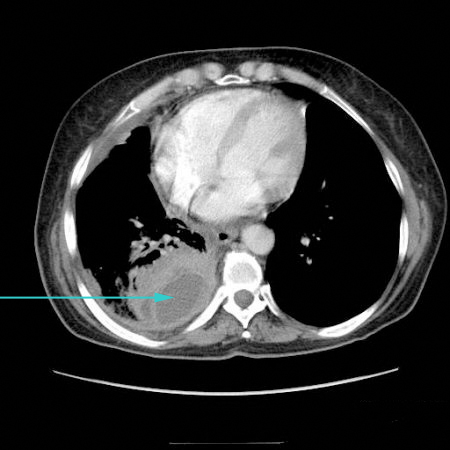

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Thoracic ultrasound image of large, simple pleural effusionFrom the collection of Dr Nicholas Maskell; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing large right pleural effusionFrom the collection of Dr Nicholas Maskell; used with permission [Citation ends].

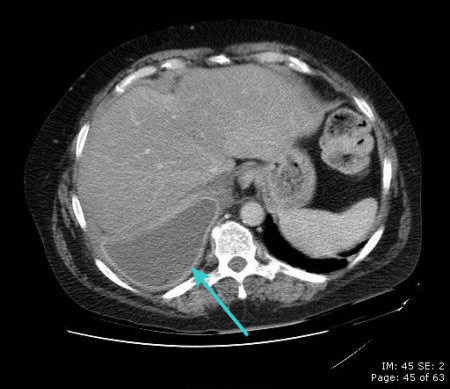

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing large right pleural effusionFrom the collection of Dr Nicholas Maskell; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing loculated pleural effusionFrom the collection of Dr Ami Rubinowitz; used with permission [Citation ends].

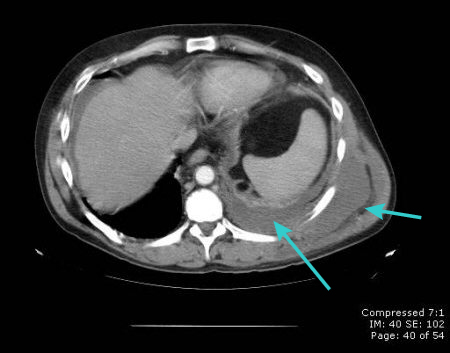

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing loculated pleural effusionFrom the collection of Dr Ami Rubinowitz; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing empyema with split pleura sign (enhancement of the thickened inner visceral and outer parietal pleura separated by a collection of pleural fluid)From the collection of Dr Ami Rubinowitz; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing empyema with split pleura sign (enhancement of the thickened inner visceral and outer parietal pleura separated by a collection of pleural fluid)From the collection of Dr Ami Rubinowitz; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of chest showing empyema necessitans (long arrow), a chronic untreated empyema that has eroded through the thoracic cage and formed a subcutaneous abscess (short arrow)From the collection of Dr Ami Rubinowitz; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of chest showing empyema necessitans (long arrow), a chronic untreated empyema that has eroded through the thoracic cage and formed a subcutaneous abscess (short arrow)From the collection of Dr Ami Rubinowitz; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing circumferential right-sided pleural thickening with significant volume loss due to mesotheliomaFrom the collection of Dr Nicholas Maskell; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing circumferential right-sided pleural thickening with significant volume loss due to mesotheliomaFrom the collection of Dr Nicholas Maskell; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing metastatic malignancy of pleuraFrom the collection of Dr Ami Rubinowitz; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing metastatic malignancy of pleuraFrom the collection of Dr Ami Rubinowitz; used with permission [Citation ends].

Other studies

Thoracocentesis: clinically significant pleural effusion >10 mm thick on ultrasonography with no known cause should be sampled through thoracocentesis under ultrasound guidance and sent for lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and protein levels. In case of exudates,[47] additional tests should be obtained, such as cell count with differential; culture; Gram stain; pH; glucose; microscopy, culture, and sensitivity; acid-fast bacilli; and cytology.[47] A pleural pH ≤7.2 implies a high-risk of complex parapneumonic effusion or pleural infection that requires drainage, if safe to perform.[18] Neutrophilic effusions are associated with an acute process, including parapneumonic effusions and acute TB; lymphocyte-predominant effusions tend to be long-standing, and can be caused by a variety of aetiologies, including malignancy and TB.[48][49][50] Pleural eosinophilia (>10% WBC count in the pleural fluid) can be suggestive of drug-induced pleuritis, although other causes of eosinophilic pleural effusions such as pneumothorax, haemothorax, pulmonary embolism, malignancy, and parasitic infections should be kept in mind.[20] Malignancy is the commonest cause of eosinophilic effusion.[51]

Pleural fluid cytology via thoracocentesis is typically done first to confirm the diagnosis of mesothelioma. However, most patients need a pleural biopsy as well because the sensitivity of pleural fluid cytology is variable.[18][52] Biopsy may be thoracoscopic (either by local anaesthetic thoracoscopy or video-assisted thoracoscopy [VATS]) or guided by CT. The use of blind closed pleural biopsy is not recommended due to low diagnostic yield.[53][54]

ECG can be useful in looking for ischaemic changes to rule in myocardial ischaemia or for signs of right heart strain (right atrial enlargement, right bundle branch block, S1Q3T3 sign, T-wave inversion in V4-V6, or right axis deviation) that might suggest pulmonary embolism.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Thoracic ultrasound image of large, simple pleural effusionFrom the collection of Dr Nicholas Maskell; used with permission [Citation ends].

Diagnostic algorithm

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Schematic showing a summary of the diagnostic approach (CXR=chest x-ray, PE-pulmonary embolism, ECG=electrocardiogram)Courtesy of Dr Ami Rubinowitz; used with permission. Updated November 2023 by BMJ Best Practice Editorial Team [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer