Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is characterised by progressive dyspnoea, cough, and a restrictive pattern on pulmonary function tests.

Diagnosis requires the exclusion of known causes of interstitial lung disease (e.g., domestic and occupational environmental exposures, connective tissue disease, and drug toxicity). The diagnosis is then confirmed by high-resolution chest CT (HRCT) patterns consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest computed tomography scan image of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisFrom the collection of Jeffrey C. Munson, MD, MS; used with permission [Citation ends]. Lung biopsy histopathology is performed when radiological and clinical data result in an uncertain diagnosis.[42]Hunninghake GW, Zimmerman MB, Schwartz DA, et al. Utility of a lung biopsy for the diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001 Jul 15;164(2):193-6.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/ajrccm.164.2.2101090#.UmESdtglgZk

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11463586?tool=bestpractice.com

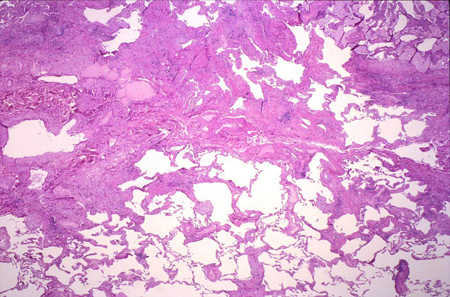

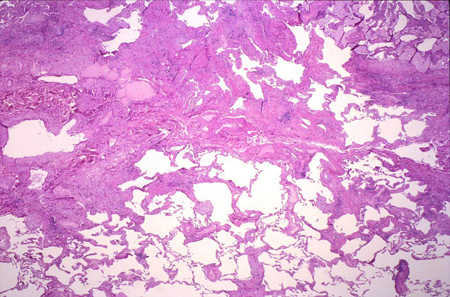

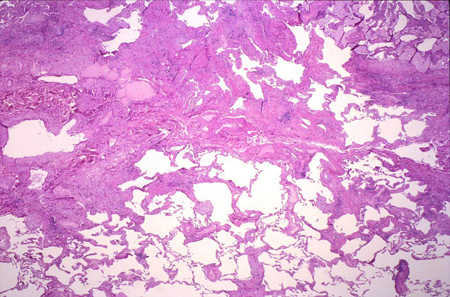

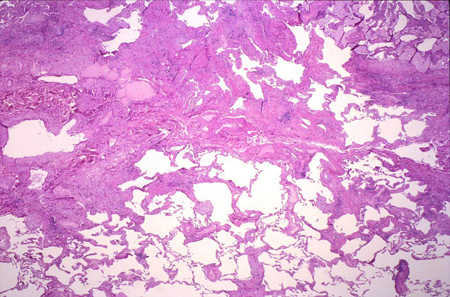

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pathology slide of usual interstitial pneumonia, the characteristic biopsy appearance of a patient with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisFrom the collection of Gregory Tino, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

Lung biopsy histopathology is performed when radiological and clinical data result in an uncertain diagnosis.[42]Hunninghake GW, Zimmerman MB, Schwartz DA, et al. Utility of a lung biopsy for the diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001 Jul 15;164(2):193-6.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/ajrccm.164.2.2101090#.UmESdtglgZk

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11463586?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pathology slide of usual interstitial pneumonia, the characteristic biopsy appearance of a patient with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisFrom the collection of Gregory Tino, MD; used with permission [Citation ends]. Surgical lung biopsy is deferred when clinical evaluation and HRCT findings support a clear diagnosis of IPF.

Surgical lung biopsy is deferred when clinical evaluation and HRCT findings support a clear diagnosis of IPF.

A multi-disciplinary approach to diagnosis, involving pulmonologists (preferably those with expertise in IPF), radiologists, and pathologists, is essential (see Diagnostic criteria and Differentials).[5]Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 May 1;205(9):e18-e47.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35486072?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, et al; ATS/ERS Committee on Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013 Sep 15;188(6):733-48.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST#.VEpLaBbgV9M

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24032382?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Hobbs S, Chung JH, Leb J, et al. Practical imaging interpretation in patients suspected of having idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: official recommendations from the radiology working group of the pulmonary fibrosis foundation. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2021 Feb;3(1):e200279.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7977697

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33778653?tool=bestpractice.com

History

Symptom onset in IPF is insidious and typically includes cough and exertional dyspnoea. Dyspnoea is the most prominent and disabling symptom. It is progressive, is not typically episodic (but is reproducible with exertion), and may have been present for >6 months before presentation.

A positive family history of IPF, cigarette smoking, advanced age (typically 50 years), and male sex increase the index of suspicion. See Assessment of dyspnoea and Assessment of chronic cough where the diagnosis is unclear.

Consider the following elements in the history.

Exclude known causes of interstitial lung disease.

Symptoms of joint inflammation and rash should be explored to exclude connective tissue disease associated with other forms of pulmonary fibrosis.

Fever is rare and suggests an alternative diagnosis.

Occupational and environmental exposures should be elicited to exclude common diseases that mimic IPF. However, certain environmental exposures have been consistently associated with the development of IPF, including vapours, gas, dust, and fumes (VGDF); metal dust; wood (pine) dust; silica dust; and agricultural dust.[28]Baumgartner KB, Samet JM, Coultas DB, et al. Occupational and environmental risk factors for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a multicenter case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000 Aug 15;152(4):307-15.

https://academic.oup.com/aje/article/152/4/307/67670

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10968375?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Gandhi SA, Min B, Fazio JC, et al. The impact of occupational exposures on the risk of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2024 Mar;21(3):486-98.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38096107?tool=bestpractice.com

Previous drug history should be sought to exclude agents causing pulmonary fibrosis that mimics IPF (e.g., amiodarone, nitrofurantoin, and bleomycin).

The patient's family history should be explored to exclude collagen vascular disease and other lung conditions, as well as to explore the possibility of familial pulmonary fibrosis.[16]Borie R, Kannengiesser C, Antoniou K, et al. European Respiratory Society statement on familial pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2023 Mar;61(3):2201383.

https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/61/3/2201383.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36549714?tool=bestpractice.com

[19]Borie R, Kannengiesser C, Sicre de Fontbrune F, et al. Management of suspected monogenic lung fibrosis in a specialised centre. Eur Respir Rev. 2017 Jun 30;26(144):160122.

https://err.ersjournals.com/content/26/144/160122.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28446600?tool=bestpractice.com

Weight loss, malaise, and fatigue may be noted.

Intermittent acute exacerbations

Some patients progress rapidly, while others progress slowly; however, a subset has a disease course characterised by intermittent acute exacerbations followed by abrupt and often permanent declines in pulmonary function.[15]Collard HR, Ryerson CJ, Corte TJ, et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. an international working group report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 Aug 1;194(3):265-75.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.201604-0801CI?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27299520?tool=bestpractice.com

An acute exacerbation is characterised as worsening dyspnoea within the past 30 days and an HRCT that demonstrates new bilateral ground-glass opacities and/or consolidation on top of the underlying changes typical of UIP. There must be no evidence of pulmonary infection, left heart failure, pulmonary embolism, or other identifiable causes of acute lung injury.[15]Collard HR, Ryerson CJ, Corte TJ, et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. an international working group report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 Aug 1;194(3):265-75.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.201604-0801CI?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27299520?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with IPF are at increased risk of hospitalisation and death due to COVID-19.[45]Aveyard P, Gao M, Lindson N, et al. Association between pre-existing respiratory disease and its treatment, and severe COVID-19: a population cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 Aug;9(8):909-23.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanres/article/PIIS2213-2600(21)00095-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33812494?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Wong AW, Shapera S, Morisset J, et al. Optimizing care for patients with interstitial lung disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med. 2020;4:226-8.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/24745332.2020.1809930

Following recovery from COVID-19, persistent respiratory symptoms should prompt evaluation for post-COVID pulmonary fibrosis and/or deterioration of pre-existing interstitial lung disease.[46]Wong AW, Shapera S, Morisset J, et al. Optimizing care for patients with interstitial lung disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med. 2020;4:226-8.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/24745332.2020.1809930

Physical examination

Lung examination typically reveals bi-basilar crackles that are 'dry' and described as 'Velcro' in quality. Asymptomatic patients may be found on routine clinical lung examinations by the presence of bi-basilar inspiratory crackles without signs or symptoms of congestive heart failure. Clubbing of the fingers can be present, particularly in more advanced disease.

The patient should be examined for signs of systemic disorders associated with interstitial lung disease, including scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, polymyositis, Sjogren syndrome, and systemic lupus erythematosus

Pulmonary function testing

This will demonstrate reductions in the diffusion capacity, often with concomitant restriction (i.e., reduced forced vital capacity, reduced total lung capacity). An isolated decrease in the lung diffusion capacity test may be seen early in the disease or if there is concomitant airway disease (e.g., COPD).

Chest x-ray

Nearly all patients with IPF have an abnormal chest radiograph at presentation.[44]Hobbs S, Chung JH, Leb J, et al. Practical imaging interpretation in patients suspected of having idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: official recommendations from the radiology working group of the pulmonary fibrosis foundation. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2021 Feb;3(1):e200279.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7977697

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33778653?tool=bestpractice.com

Chest x-ray may show basilar, peripheral, bilateral, asymmetrical, or reticular opacities.[44]Hobbs S, Chung JH, Leb J, et al. Practical imaging interpretation in patients suspected of having idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: official recommendations from the radiology working group of the pulmonary fibrosis foundation. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2021 Feb;3(1):e200279.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7977697

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33778653?tool=bestpractice.com

Some patients may present with mild or even absent, symptoms subsequent to a chest x-ray obtained for other reasons. This may show evidence of fibrotic changes.

Chest x-ray is also of use in evaluating alternative diagnoses, especially in acute exacerbations.[47]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: chronic dyspnea-noncardiovascular origin. 2024 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69448/Narrative

[48]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: diffuse lung disease. 2021 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/3157911/Narrative

Chest high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT)

All patients with a suspected diagnosis of IPF should undergo chest HRCT.[48]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: diffuse lung disease. 2021 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/3157911/Narrative

Guidelines for the diagnosis of IPF state that HRCT should be categorised by the certainty that findings represent an underlying pathology of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP).[5]Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 May 1;205(9):e18-e47.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35486072?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Hobbs S, Chung JH, Leb J, et al. Practical imaging interpretation in patients suspected of having idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: official recommendations from the radiology working group of the pulmonary fibrosis foundation. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2021 Feb;3(1):e200279.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7977697

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33778653?tool=bestpractice.com

This may require multi-disciplinary evaluation.[44]Hobbs S, Chung JH, Leb J, et al. Practical imaging interpretation in patients suspected of having idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: official recommendations from the radiology working group of the pulmonary fibrosis foundation. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2021 Feb;3(1):e200279.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7977697

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33778653?tool=bestpractice.com

A UIP pattern on HRCT includes subpleural and basilar-predominant reticular abnormalities with honeycombing. Traction bronchiectasis may or may not be present.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest computed tomography scan image of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisFrom the collection of Jeffrey C. Munson, MD, MS; used with permission [Citation ends].

The following features are inconsistent with UIP and should be absent:

Upper or mid-lung predominance

Peribronchovascular or perilymphatic predominance

Predominant ground glass opacities

Profuse micronodules

Centrilobular nodules

Discrete pulmonary nodules

Discrete cysts

Marked mosaic attenuation suggestive of air trapping

Consolidation

If honeycombing is absent but the other features are present, the HRCT represents probable UIP.[5]Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 May 1;205(9):e18-e47.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35486072?tool=bestpractice.com

The diagnostic sensitivity (71% to 90%), specificity (64% to 95%), and positive predictive value (79% to 100%) of HRCT for IPF depends on the level of certainty reported by the interpreting radiologist.[1]Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Sep 1;198(5):e44-68.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30168753?tool=bestpractice.com

In patients with a suggestive history and clinical examination, and without an identifiable alternative diagnosis, an HRCT pattern of UIP is sufficient to diagnose IPF without additional, more invasive studies.[5]Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 May 1;205(9):e18-e47.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35486072?tool=bestpractice.com

If HRCT demonstrates probable UIP, a surgical lung biopsy is only required if there is clinical uncertainty concerning alternative diagnoses.[5]Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 May 1;205(9):e18-e47.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35486072?tool=bestpractice.com

The ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT guidelines classify an indeterminate pattern as subpleural and basilar-predominant disease that shows subtle reticulation, with or without mild ground glass opacities or distortion.[5]Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 May 1;205(9):e18-e47.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35486072?tool=bestpractice.com

This indeterminate pattern probably suggests early IPF. Similar guidelines published by the Fleischner Society in 2018 define an indeterminate HRCT pattern differently, requiring only that it shows variable or diffuse distribution with some features suggestive of a non-UIP pattern.[49]Lynch DA, Sverzellati N, Travis WD, et al. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a Fleischner Society White Paper. Lancet Respir Med. 2017 Nov 15;6(2):138-53.

https://spiral.imperial.ac.uk:8443/handle/10044/1/56696

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29154106?tool=bestpractice.com

This may represent a disease process that is distinct from IPF.

MRI studies

MRI is not suitable for the evaluation of interstitial lung disease, but it may be used where other disease is suspected.[44]Hobbs S, Chung JH, Leb J, et al. Practical imaging interpretation in patients suspected of having idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: official recommendations from the radiology working group of the pulmonary fibrosis foundation. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2021 Feb;3(1):e200279.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7977697

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33778653?tool=bestpractice.com

[47]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: chronic dyspnea-noncardiovascular origin. 2024 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69448/Narrative

[48]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: diffuse lung disease. 2021 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/3157911/Narrative

Laboratory tests

There are no specific laboratory abnormalities in IPF.

Routine laboratory evaluation can, however, exclude systemic disorders. The 2018 ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT guidelines recommend serological testing for most patients. This should include C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, anti-nuclear antibody by immunofluorescence, rheumatoid factor, myositis panel, and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide.

Serological tests for other connective tissue diseases may be ordered based on the clinical picture. Mild anti-nuclear antibody and rheumatoid factor elevations are common in IPF and do not exclude a diagnosis of IPF, provided there are no other clinical or serological signs of connective tissue disease.[1]Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Sep 1;198(5):e44-68.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30168753?tool=bestpractice.com

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)

The diagnostic value of BAL in IPF is limited. It is not recommended in patients with an HRCT that demonstrates a UIP pattern.[5]Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 May 1;205(9):e18-e47.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35486072?tool=bestpractice.com

If a confident UIP pattern cannot be identified on HRCT, BAL for differential cell count may be a useful adjunct, as specific patterns such as an isolated elevation of lymphocytes (>40%) are unusual in IPF and suggest alternate diagnoses such as chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis.[5]Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 May 1;205(9):e18-e47.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35486072?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]Meyer KC, Raghu G, Baughman RP, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: the clinical utility of bronchoalveolar lavage cellular analysis in interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012 May 1;185(9):1004-14.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22550210?tool=bestpractice.com

Trans-bronchial lung biopsy and cryobiopsy

Trans-bronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) may have a role when the clinical evaluation suggests an alternative diagnosis, centrilobular zones are involved, or the pathology is not complex (e.g., carcinomatous lymphangitis, sarcoidosis, organising pneumonia, and diffuse alveolar damage).[51]Korevaar DA, Colella S, Fally M, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines on transbronchial lung cryobiopsy in the diagnosis of interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir J. 2022 Nov;60(5):2200425.

https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/60/5/2200425.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35710261?tool=bestpractice.com

Although TBLB has historically demonstrated poor diagnostic yield due to small specimens, sampling errors, and crush artefacts, the use of genomic classifiers on TBLB specimens may improve its clinical utility.[52]Kim SY, Diggans J, Pankratz D, et al. Classification of usual interstitial pneumonia in patients with interstitial lung disease: assessment of a machine learning approach using high-dimensional transcriptional data. Lancet Respir Med. 2015 Jun;3(6):473-82.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26003389?tool=bestpractice.com

[53]Lasky JA, Case A, Unterman A, et al. The impact of the Envisia genomic classifier in the diagnosis and management of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022 Jun;19(6):916-24.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202107-897OC?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34889723?tool=bestpractice.com

The 2022 ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT guidelines recommend trans-bronchial cryobiopsy (TBLC) as an acceptable alternative to surgical lung biopsy for histopathological diagnosis, provided there is clinical expertise in both performing and interpreting the investigation.[5]Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 May 1;205(9):e18-e47.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35486072?tool=bestpractice.com

[51]Korevaar DA, Colella S, Fally M, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines on transbronchial lung cryobiopsy in the diagnosis of interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir J. 2022 Nov;60(5):2200425.

https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/60/5/2200425.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35710261?tool=bestpractice.com

Diagnostic yields are estimated at 80% with trans-bronchial biopsy compared with 90% for surgical biopsy; risks of pneumothorax and severe bleeding are similar.[5]Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 May 1;205(9):e18-e47.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35486072?tool=bestpractice.com

Surgical lung biopsy

Surgical lung biopsy, usually by video-assisted thoracoscopy, is crucial in the evaluation of patients with a history, clinical evaluation, and HRCT findings that do not support a clear diagnosis of IPF.

Histologically, UIP on surgical lung biopsy is characterised by fibrosis of varying ages (i.e., temporal heterogeneity), with areas of normal lung next to areas of honeycombing and areas of more active scar formation, including fibroblastic foci. The interstitial inflammation is typically mild to moderate and found in a patchy distribution.[5]Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 May 1;205(9):e18-e47.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35486072?tool=bestpractice.com

[54]Katzenstein AL, Myers JL. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: clinical relevance of pathologic classification. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998 Apr;157(4 Pt 1):1301-15.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9707039#.UmEVMdglgZk

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9563754?tool=bestpractice.com

The histopathological classification of UIP is based on four patterns:[5]Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 May 1;205(9):e18-e47.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35486072?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pathology slide of usual interstitial pneumonia, the characteristic biopsy appearance of a patient with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisFrom the collection of Gregory Tino, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

UIP pattern

Probable UIP pattern

Indeterminate for UIP

Alternative diagnosis

Surgical lung biopsy is considered the gold standard for diagnosing IPF, but it should it should only be considered in cases of diagnostic uncertainty given the risk for procedural complications (e.g., ILD exacerbation).[55]Bando M, Ohno S, Hosono T, et al. Risk of acute exacerbation after video-assisted thoracoscopic lung biopsy for interstitial lung disease. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2009 Oct;16(4):229-35.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23168584?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Ghatol A, Ruhl AP, Danoff SK. Exacerbations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis triggered by pulmonary and nonpulmonary surgery: a case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Lung. 2012 Aug;190(4):373-80.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22543997?tool=bestpractice.com

Surgical lung biopsy should not be interpreted in isolation from other clinical findings because not all patients with UIP on biopsy have clinical IPF. Other causes of UIP, such as collagen vascular disease and drug toxicity, should be examined and excluded before biopsy. Multiple samples, preferably from at least two distinct anatomical sites, are typically required to confidently diagnose UIP.

Lung biopsy histopathology is performed when radiological and clinical data result in an uncertain diagnosis.[42][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pathology slide of usual interstitial pneumonia, the characteristic biopsy appearance of a patient with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisFrom the collection of Gregory Tino, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

Lung biopsy histopathology is performed when radiological and clinical data result in an uncertain diagnosis.[42][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pathology slide of usual interstitial pneumonia, the characteristic biopsy appearance of a patient with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisFrom the collection of Gregory Tino, MD; used with permission [Citation ends]. Surgical lung biopsy is deferred when clinical evaluation and HRCT findings support a clear diagnosis of IPF.

Surgical lung biopsy is deferred when clinical evaluation and HRCT findings support a clear diagnosis of IPF.