The evaluation of RAS includes consideration of factors in the patient's history and decisions on the appropriate imaging modalities.

History

Age of onset of hypertension may be suggestive of the underlying aetiology of RAS:

<30 years suggests fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD).[7]Kaplan NM. Renovascular hypertension. In: Kaplan NM, ed. Clinical hypertension. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:381-403.[16]Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, et al. Management of patients with peripheral artery disease (compilation of 2005 and 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline recommendations): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Apr 2;127(13):1425-43.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/127/13/1425.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23457117?tool=bestpractice.com

>55 years suggests atherosclerotic RAS.[7]Kaplan NM. Renovascular hypertension. In: Kaplan NM, ed. Clinical hypertension. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:381-403.[16]Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, et al. Management of patients with peripheral artery disease (compilation of 2005 and 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline recommendations): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Apr 2;127(13):1425-43.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/127/13/1425.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23457117?tool=bestpractice.com

Sudden or unexplained recurrent pulmonary oedema is suggestive of RAS:[7]Kaplan NM. Renovascular hypertension. In: Kaplan NM, ed. Clinical hypertension. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:381-403.[16]Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, et al. Management of patients with peripheral artery disease (compilation of 2005 and 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline recommendations): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Apr 2;127(13):1425-43.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/127/13/1425.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23457117?tool=bestpractice.com

[17]Aboyans V, Ricco JB, Bartelink ME, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur Heart J. 2018 Mar 1;39(9):763-816.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/doi/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx095/4095038/2017-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-Diagnosis-and-Treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28886620?tool=bestpractice.com

[18]Davenport A, Anker SD, Mebazaa A, et al.; Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Consensus Group. ADQI 7: the clinical management of the Cardio-Renal syndromes: work group statements from the 7th ADQI consensus conference. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010 Jul;25(7):2077-89.

https://academic.oup.com/ndt/article/25/7/2077/1874047/ADQI-7-the-clinical-management-of-the-Cardio-Renal

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20494894?tool=bestpractice.com

Hypertension (accelerated, malignant, or resistant)

Patients with either atherosclerotic or FMD form of RAS can present with severe, progressive, and/or difficult-to-control hypertension, sometimes causing end-organ damage.[7]Kaplan NM. Renovascular hypertension. In: Kaplan NM, ed. Clinical hypertension. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:381-403.[16]Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, et al. Management of patients with peripheral artery disease (compilation of 2005 and 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline recommendations): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Apr 2;127(13):1425-43.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/127/13/1425.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23457117?tool=bestpractice.com

[19]Hicks CW, Clark TWI, Cooper CJ, et al. Atherosclerotic renovascular disease: a KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) controversies conference. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022 Feb;79(2):289-301.

https://www.doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.06.025

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34384806?tool=bestpractice.com

Kidney dysfunction or acute kidney injury:

Unexplained kidney dysfunction may result from progressive stenosis or hypertension-related end-organ damage.[2]Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic). Circulation. 2006 Mar 21;113(11):e463-654.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/113/11/e463.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16549646?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Kaplan NM. Renovascular hypertension. In: Kaplan NM, ed. Clinical hypertension. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:381-403.

Acute kidney injury can be seen in some patients with bilateral RAS or RAS of a single functioning kidney after starting an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor antagonist.[2]Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic). Circulation. 2006 Mar 21;113(11):e463-654.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/113/11/e463.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16549646?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Kaplan NM. Renovascular hypertension. In: Kaplan NM, ed. Clinical hypertension. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:381-403.[19]Hicks CW, Clark TWI, Cooper CJ, et al. Atherosclerotic renovascular disease: a KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) controversies conference. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022 Feb;79(2):289-301.

https://www.doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.06.025

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34384806?tool=bestpractice.com

Clinical factors predisposing to atherosclerotic RAS include:[2]Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic). Circulation. 2006 Mar 21;113(11):e463-654.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/113/11/e463.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16549646?tool=bestpractice.com

[19]Hicks CW, Clark TWI, Cooper CJ, et al. Atherosclerotic renovascular disease: a KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) controversies conference. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022 Feb;79(2):289-301.

https://www.doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.06.025

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34384806?tool=bestpractice.com

Multivessel coronary artery disease (CAD)

Other peripheral vascular disease (PVD)

Unexplained congestive heart failure (CHF)

Refractory angina

Dyslipidaemia

Smoking (implicated in aetiology of both atherosclerotic and FMD types of RAS)[1]Safian RD, Textor SC. Renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2001 Feb 8;344(6):431-42.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11172181?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Gornik HL, Persu A, Adlam D, et al. First International Consensus on the diagnosis and management of fibromuscular dysplasia. Vasc Med. 2019 Jan 16;24(2):164-89.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1358863X18821816

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30648921?tool=bestpractice.com

Absence of family history of hypertension - may be suggestive of RAS as a cause of hypertension.[2]Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic). Circulation. 2006 Mar 21;113(11):e463-654.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/113/11/e463.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16549646?tool=bestpractice.com

[13]Eisenhauer AC, White CJ. Endovascular treatment of noncoronary obstructive vascular disease. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, et al., eds. Braunwald's heart disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2008:1532-5.

Examination

Given that RAS can only conclusively be diagnosed with imaging, suggestive findings on examination include:

Hypertension on BP measurement

Abdominal bruit: the finding of an abdominal bruit should raise the suspicion for the presence of RAS[2]Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic). Circulation. 2006 Mar 21;113(11):e463-654.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/113/11/e463.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16549646?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Kaplan NM. Renovascular hypertension. In: Kaplan NM, ed. Clinical hypertension. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:381-403.

Other bruits: bruits in other vessels are frequent due to the common pathophysiology and high prevalence of co-existent PVD.[13]Eisenhauer AC, White CJ. Endovascular treatment of noncoronary obstructive vascular disease. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, et al., eds. Braunwald's heart disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2008:1532-5.

General investigations

Serum creatinine to estimate glomerular filtration rate.[1]Safian RD, Textor SC. Renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2001 Feb 8;344(6):431-42.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11172181?tool=bestpractice.com

Serum potassium: hypokalaemia or low-to-normal potassium may suggest activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.[7]Kaplan NM. Renovascular hypertension. In: Kaplan NM, ed. Clinical hypertension. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:381-403.

Urinalysis and sediment evaluation (to exclude glomerular disease): RAS, in the absence of co-existent diabetic nephropathy or hypertensive nephrosclerosis, is typically non-proteinuric without abnormalities in the urinary sediment.[4]Chonchol M, Linas S. Diagnosis and management of ischemic nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006 Mar;1(2):172-81.

http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/content/1/2/172.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17699206?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Zucchelli PC. Hypertension and atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: diagnostic approach. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002 Nov;13 Suppl 3:S184-6.

http://jasn.asnjournals.org/content/13/suppl_3/S184.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12466311?tool=bestpractice.com

Evaluation of secondary causes of hypertension as indicated should be excluded and considered in the differential diagnosis: for example, aldosterone to renin ratio (ratio <20 excludes primary hyperaldosteronism).[7]Kaplan NM. Renovascular hypertension. In: Kaplan NM, ed. Clinical hypertension. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:381-403.

Choice of imaging

In addition to basic laboratory data, controversy remains as to what imaging modality is most appropriate. While ultrasonography offers a safe, non-invasive assessment, its sensitivity and specificity are lower than other modalities, and its use provides only indirect evidence of the presence of stenosis. Other non-invasive techniques (i.e., CT angiography or MR angiography) have a risk associated with the use of contrast media (radiocontrast nephropathy and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, respectively). Conventional angiography, despite its procedural risk (e.g., atheroemboli, bleeding) and the risk of radiocontrast nephropathy, has the advantage of being able to determine the clinical significance of the lesions by measurement of the pressure gradient across a stenotic lesion, and the possibility of concurrently performing endovascular therapy. Alternative imaging modalities that experts might consider in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) include non-contrast magnetic resonance angiography[21]Utsunomiya D, Miyazaki M, Nomitsu Y, et al. Clinical role of non-contrast magnetic resonance angiography for evaluation of renal artery stenosis. Circ J. 2008 Oct;72(10):1627-30.

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/circj/72/10/72_CJ-08-0005/_pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18728334?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]Khoo MM, Deeab D, Gedroyc WM, et al. Renal artery stenosis: comparative assessment by unenhanced renal artery MRA versus contrast-enhanced MRA. Eur Radiol. 2011 Jul;21(7):1470-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21337034?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]Angeretti MG, Lumia D, Canì A, et al. Non-enhanced MR angiography of renal arteries: comparison with contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Acta Radiol. 2013 Sep;54(7):749-56.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23550187?tool=bestpractice.com

and invasive angiography with carbon dioxide (CO2).[24]Caridi JG, Stavropoulos SW, Hawkins IF Jr. CO2 digital subtraction angiography for renal artery angioplasty in high-risk patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999 Dec;173(6):1551-6.

http://www.ajronline.org/doi/pdf/10.2214/ajr.173.6.10584800

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10584800?tool=bestpractice.com

[25]Lorch H, Steinhoff J, Fricke L, et al. CO2 angiography of transplanted kidneys [in German]. Rontgenpraxis. 2003;55(1):26-32.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12650035?tool=bestpractice.com

[26]Liss P, Eklöf H, Hellberg O, et al. Renal effects of CO2 and iodinated contrast media in patients undergoing renovascular intervention: a prospective, randomized study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005 Jan;16(1):57-65.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15640411?tool=bestpractice.com

It is recommended to start with a non-invasive imaging test in patients with a high clinical probability of RAS.

A patient's risk is determined by the clinician's index of suspicion, based on the patient's demographics (onset of hypertension at age <30 years or >55 years), comorbid conditions (PVD, CAD, CVA), and clinical condition (hypertension refractory to >3 antihypertensive agents).

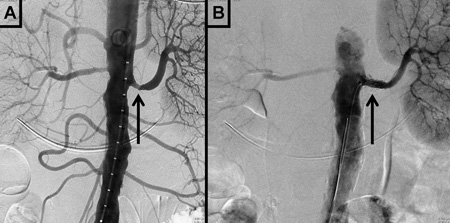

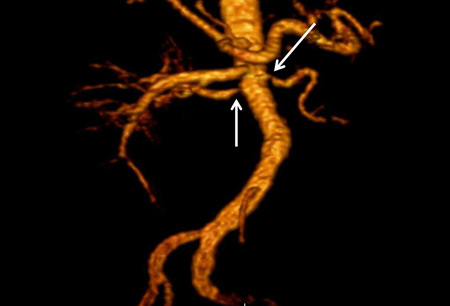

If the results of non-invasive tests are inconclusive and the clinical suspicion for RAS is high, invasive testing is recommended.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Magnetic resonance angiography (3-dimensional volume rendered reconstruction) in a patient with significant bilateral atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Arrows indicate proximal bilateral stenosesCourtesy of David J. Sheehan, DO; Radiology Department, University of Massachusetts Medical Center and Medical School [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Magnetic resonance angiography (maximum-intensity projection) in a patient with fibromuscular dysplasia of the renal arteries. Arrow indicates the characteristic irregular contour in the right renal arteryCourtesy of Raul Galvez, MD, MPH and Hale Ersoy, MD; Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School [Citation ends].

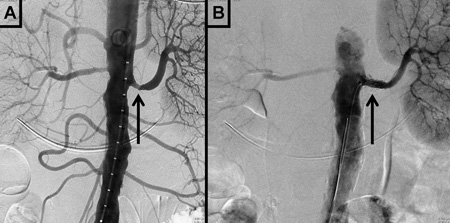

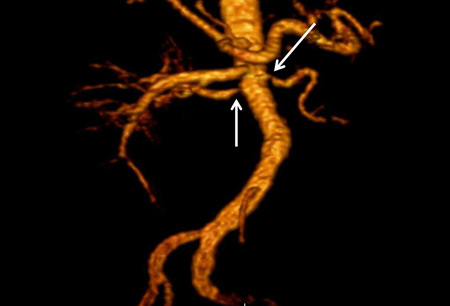

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Magnetic resonance angiography (maximum-intensity projection) in a patient with fibromuscular dysplasia of the renal arteries. Arrow indicates the characteristic irregular contour in the right renal arteryCourtesy of Raul Galvez, MD, MPH and Hale Ersoy, MD; Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Digital subtraction angiography in a patient with significant atherosclerotic left renal artery stenosis. Panel A, prior to stent placement. Panel B, after successful stent deployment. Arrows indicate the site of stenosis and stent placement in their respective panelsCourtesy of Alvaro Alonso, MD and Scott J. Gilbert, MD [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Digital subtraction angiography in a patient with significant atherosclerotic left renal artery stenosis. Panel A, prior to stent placement. Panel B, after successful stent deployment. Arrows indicate the site of stenosis and stent placement in their respective panelsCourtesy of Alvaro Alonso, MD and Scott J. Gilbert, MD [Citation ends].

Non-invasive imaging

It is reasonable to begin with a renal duplex ultrasound, followed if necessary by CT angiography, MR angiography, or a captopril renal scan. Non-contrast MR angiography sequences can be considered in patients with CKD.[21]Utsunomiya D, Miyazaki M, Nomitsu Y, et al. Clinical role of non-contrast magnetic resonance angiography for evaluation of renal artery stenosis. Circ J. 2008 Oct;72(10):1627-30.

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/circj/72/10/72_CJ-08-0005/_pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18728334?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]Khoo MM, Deeab D, Gedroyc WM, et al. Renal artery stenosis: comparative assessment by unenhanced renal artery MRA versus contrast-enhanced MRA. Eur Radiol. 2011 Jul;21(7):1470-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21337034?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]Angeretti MG, Lumia D, Canì A, et al. Non-enhanced MR angiography of renal arteries: comparison with contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Acta Radiol. 2013 Sep;54(7):749-56.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23550187?tool=bestpractice.com

Duplex ultrasound (sensitivity 84% to 98%, specificity 62% to 99%). Can identify discrepancy in kidney size and velocity of renal blood flow.[4]Chonchol M, Linas S. Diagnosis and management of ischemic nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006 Mar;1(2):172-81.

http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/content/1/2/172.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17699206?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, et al. Management of patients with peripheral artery disease (compilation of 2005 and 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline recommendations): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Apr 2;127(13):1425-43.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/127/13/1425.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23457117?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Zucchelli PC. Hypertension and atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: diagnostic approach. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002 Nov;13 Suppl 3:S184-6.

http://jasn.asnjournals.org/content/13/suppl_3/S184.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12466311?tool=bestpractice.com

Ultrasound diagnostic criteria for significant renal artery stenosis are:[27]Gerhard-Herman M, Gardin JM, Jaff M, et al. Guidelines for noninvasive vascular laboratory testing: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology. Vasc Med. 2006 Nov;11(3):183-200.

http://vmj.sagepub.com/content/11/3/183.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17288127?tool=bestpractice.com

Renal resistive index >0.8 was used as a criterion historically, but as resistive index is now known to be influenced by extrarenal factors such as systemic haemodynamics, it is no longer routinely used in the diagnosis of RAS.[28]Hashimoto J, Ito S. Central pulse pressure and aortic stiffness determine renal hemodynamics: pathophysiological implication for microalbuminuria in hypertension. Hypertension. 2011 Nov;58(5):839-46.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.177469

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21968753?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]O'Neill WC. Renal resistive index: a case of mistaken identity. Hypertension. 2014 Nov;64(5):915-7.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04183

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25156171?tool=bestpractice.com

Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (sensitivity 90% to 100%, specificity 76% to 94%).[2]Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic). Circulation. 2006 Mar 21;113(11):e463-654.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/113/11/e463.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16549646?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Chonchol M, Linas S. Diagnosis and management of ischemic nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006 Mar;1(2):172-81.

http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/content/1/2/172.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17699206?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, et al. Management of patients with peripheral artery disease (compilation of 2005 and 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline recommendations): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Apr 2;127(13):1425-43.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/127/13/1425.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23457117?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Zucchelli PC. Hypertension and atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: diagnostic approach. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002 Nov;13 Suppl 3:S184-6.

http://jasn.asnjournals.org/content/13/suppl_3/S184.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12466311?tool=bestpractice.com

Noncontrast MR angiography sequences can be considered in patients with CKD.[21]Utsunomiya D, Miyazaki M, Nomitsu Y, et al. Clinical role of non-contrast magnetic resonance angiography for evaluation of renal artery stenosis. Circ J. 2008 Oct;72(10):1627-30.

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/circj/72/10/72_CJ-08-0005/_pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18728334?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]Khoo MM, Deeab D, Gedroyc WM, et al. Renal artery stenosis: comparative assessment by unenhanced renal artery MRA versus contrast-enhanced MRA. Eur Radiol. 2011 Jul;21(7):1470-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21337034?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]Angeretti MG, Lumia D, Canì A, et al. Non-enhanced MR angiography of renal arteries: comparison with contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Acta Radiol. 2013 Sep;54(7):749-56.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23550187?tool=bestpractice.com

CT angiography (sensitivity 59% to 96%, specificity 82% to 99%).[2]Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic). Circulation. 2006 Mar 21;113(11):e463-654.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/113/11/e463.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16549646?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Chonchol M, Linas S. Diagnosis and management of ischemic nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006 Mar;1(2):172-81.

http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/content/1/2/172.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17699206?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Zucchelli PC. Hypertension and atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: diagnostic approach. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002 Nov;13 Suppl 3:S184-6.

http://jasn.asnjournals.org/content/13/suppl_3/S184.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12466311?tool=bestpractice.com

[30]Olbricht CJ, Paul K, Prokop M, et al. Minimally invasive diagnosis of renal artery stenosis by spiral computed tomography angiography. Kidney Int. 1995 Oct;48(4):1332-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8569096?tool=bestpractice.com

Captopril renal scan (sensitivity 45% to 94%, specificity 81% to 100%) has a less relevant contemporary role because of its complexity, poor sensitivity, and the availability of easier and more accurate tests.[2]Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic). Circulation. 2006 Mar 21;113(11):e463-654.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/113/11/e463.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16549646?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Chonchol M, Linas S. Diagnosis and management of ischemic nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006 Mar;1(2):172-81.

http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/content/1/2/172.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17699206?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Zucchelli PC. Hypertension and atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: diagnostic approach. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002 Nov;13 Suppl 3:S184-6.

http://jasn.asnjournals.org/content/13/suppl_3/S184.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12466311?tool=bestpractice.com

The American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association and the European Society of Cardiology/European Stroke Association/European Society of Vascular Surgery do not recommend captopril renal scan for diagnosing RAS.[16]Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, et al. Management of patients with peripheral artery disease (compilation of 2005 and 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline recommendations): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Apr 2;127(13):1425-43.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/127/13/1425.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23457117?tool=bestpractice.com

[17]Aboyans V, Ricco JB, Bartelink ME, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur Heart J. 2018 Mar 1;39(9):763-816.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/doi/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx095/4095038/2017-ESC-Guidelines-on-the-Diagnosis-and-Treatment

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28886620?tool=bestpractice.com

Invasive testing

Conventional angiography:[2]Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic). Circulation. 2006 Mar 21;113(11):e463-654.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/113/11/e463.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16549646?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Chonchol M, Linas S. Diagnosis and management of ischemic nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006 Mar;1(2):172-81.

http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/content/1/2/172.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17699206?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Zucchelli PC. Hypertension and atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: diagnostic approach. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002 Nov;13 Suppl 3:S184-6.

http://jasn.asnjournals.org/content/13/suppl_3/S184.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12466311?tool=bestpractice.com

The most sensitive and specific test for assessing anatomical narrowing of the renal artery.

Also allows for therapeutic intervention at the same time.

Requires arterial catheterisation and contrast utilisation.

Additional diagnostic modalities may be used during invasive angiography (such as the evaluation of pressure gradients, the use of pressure wires to evaluate lesion physiology, or intravascular ultrasound). Likewise, carbon dioxide angiography may be performed in specialised centres in patients with CKD.[24]Caridi JG, Stavropoulos SW, Hawkins IF Jr. CO2 digital subtraction angiography for renal artery angioplasty in high-risk patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999 Dec;173(6):1551-6.

http://www.ajronline.org/doi/pdf/10.2214/ajr.173.6.10584800

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10584800?tool=bestpractice.com

[25]Lorch H, Steinhoff J, Fricke L, et al. CO2 angiography of transplanted kidneys [in German]. Rontgenpraxis. 2003;55(1):26-32.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12650035?tool=bestpractice.com

[26]Liss P, Eklöf H, Hellberg O, et al. Renal effects of CO2 and iodinated contrast media in patients undergoing renovascular intervention: a prospective, randomized study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005 Jan;16(1):57-65.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15640411?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Magnetic resonance angiography (maximum-intensity projection) in a patient with fibromuscular dysplasia of the renal arteries. Arrow indicates the characteristic irregular contour in the right renal arteryCourtesy of Raul Galvez, MD, MPH and Hale Ersoy, MD; Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Magnetic resonance angiography (maximum-intensity projection) in a patient with fibromuscular dysplasia of the renal arteries. Arrow indicates the characteristic irregular contour in the right renal arteryCourtesy of Raul Galvez, MD, MPH and Hale Ersoy, MD; Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Digital subtraction angiography in a patient with significant atherosclerotic left renal artery stenosis. Panel A, prior to stent placement. Panel B, after successful stent deployment. Arrows indicate the site of stenosis and stent placement in their respective panelsCourtesy of Alvaro Alonso, MD and Scott J. Gilbert, MD [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Digital subtraction angiography in a patient with significant atherosclerotic left renal artery stenosis. Panel A, prior to stent placement. Panel B, after successful stent deployment. Arrows indicate the site of stenosis and stent placement in their respective panelsCourtesy of Alvaro Alonso, MD and Scott J. Gilbert, MD [Citation ends].