Diagnosis of MDS requires a detailed medical history and physical examination, and pathological assessment of the peripheral blood and bone marrow.

MDS is a heterogeneous disease with varying presentations. Patients are often asymptomatic at presentation, and MDS is suspected following a routine blood test showing cytopenia (most commonly anaemia).[47]Garcia-Manero G. Myelodysplastic syndromes: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2023 Aug;98(8):1307-25.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26984

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37288607?tool=bestpractice.com

Some patients present with symptoms related to cytopenia (e.g., fatigue, infections, bruising).

History and physical examination

Median age at diagnosis is 70-75 years, but the disease can occur at any age and should be considered in younger patients who have had prior exposure to chemotherapy or radiotherapy, or who have a congenital disorder (e.g., Fanconi syndrome, Bloom syndrome, Down syndrome).[9]Sekeres MA, Taylor J. Diagnosis and treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes: a review. JAMA. 2022 Sep 6;328(9):872-80.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36066514?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Roman E, Smith A, Appleton S, et al. Myeloid malignancies in the real-world: occurrence, progression and survival in the UK's population-based Haematological Malignancy Research Network 2004-15. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016 Jun;42:186-98.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877782116300364

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27090942?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: myelodysplastic syndromes [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[16]Fenaux P, Haase D, Santini V, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Myelodysplastic syndromes: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021 Feb;32(2):142-56.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(20)43129-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33221366?tool=bestpractice.com

[18]Sperling AS, Gibson CJ, Ebert BL. The genetics of myelodysplastic syndrome: from clonal haematopoiesis to secondary leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017 Jan;17(1):5-19.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27834397?tool=bestpractice.com

[26]Oetjen KA, Levoska MA, Tamura D, et al. Predisposition to hematologic malignancies in patients with xeroderma pigmentosum. Haematologica. 2020 Apr;105(4):e144-6.

https://www.doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2019.223370

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31439674?tool=bestpractice.com

[27]Aktas D, Koc A, Boduroglu K, et al. Myelodysplastic syndrome associated with monosomy 7 in a child with Bloom syndrome. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2000 Jan;116(1):44-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10616531?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Sill H, Olipitz W, Zebisch A, et al. Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms: pathobiology and clinical characteristics. Br J Pharmacol. 2011 Feb;162(4):792-805.

https://bpspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01100.x

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21039422?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Kaplan H, Malmgren J, De Roos AJ. Risk of myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia post radiation treatment for breast cancer: a population-based study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013 Feb;137(3):863-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23274844?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]Sallman DA, Padron E. Myelodysplasia in younger adults: outlier or unique molecular entity? Haematologica. 2017 Jun;102(6):967-8.

https://www.doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2017.165993

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28566339?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Hirsch CM, Przychodzen BP, Radivoyevitch T, et al. Molecular features of early onset adult myelodysplastic syndrome. Haematologica. 2017 Jun;102(6):1028-34.

https://www.doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2016.159772

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28255022?tool=bestpractice.com

History should include a careful assessment of prior exposure to chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy; prior infections or bleeding episodes; presence of comorbid conditions; family history of haematological disorders; nutritional status (nutrient deficiencies); alcohol use; and exposure to toxic chemicals.[11]Killick SB, Wiseman DH, Quek L, et al. British Society for Haematology guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of prognosis of adult myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 2021 Jul;194(2):282-93.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.17621

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34137023?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: myelodysplastic syndromes [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

A careful physical examination is required which may identify signs and symptoms related to cytopenias, such as pallor, fatigue, exercise intolerance, infections (usually bacterial), bruising, and bleeding (petechiae, purpura).

Autoimmune disorders (e.g., vasculitis, connective tissue disease, inflammatory arthritis) are reported in approximately 25% of MDS patients.[6]Wolach O, Stone R. Autoimmunity and inflammation in myelodysplastic syndromes. Acta Haematol. 2016;136(2):108-17.

https://www.doi.org/10.1159/000446062

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27337745?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Komrokji RS, Kulasekararaj A, Al Ali NH, et al. Autoimmune diseases and myelodysplastic syndromes. Am J Hematol. 2016 May;91(5):E280-3.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/ajh.24333

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26875020?tool=bestpractice.com

[8]Enright H, Jacobs HS, Vercellotti G, et al. Paraneoplastic autoimmune phenomena in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes: response to immunosuppressive therapy. Br J Haematol. 1995 Oct;91(2):403-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8547082?tool=bestpractice.com

Splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and lymphadenopathy rarely occur in MDS. They can occur in chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (CMML), a myeloid neoplasm with pathological and molecular features that overlap with MDS.[1]Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization classification of haematolymphoid tumours: myeloid and histiocytic/dendritic neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022 Jul;36(7):1703-19.

https://www.doi.org/10.1038/s41375-022-01613-1

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732831?tool=bestpractice.com

Initial testing

The initial tests should be a full blood count (FBC) with differential, and a peripheral smear. The FBC will show one or more cytopenias (most commonly anaemia) that are sustained (e.g., >4 months).[11]Killick SB, Wiseman DH, Quek L, et al. British Society for Haematology guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of prognosis of adult myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 2021 Jul;194(2):282-93.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.17621

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34137023?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: myelodysplastic syndromes [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[16]Fenaux P, Haase D, Santini V, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Myelodysplastic syndromes: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021 Feb;32(2):142-56.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(20)43129-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33221366?tool=bestpractice.com

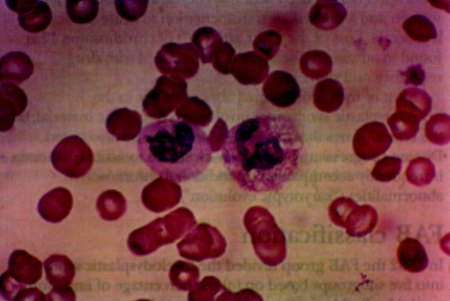

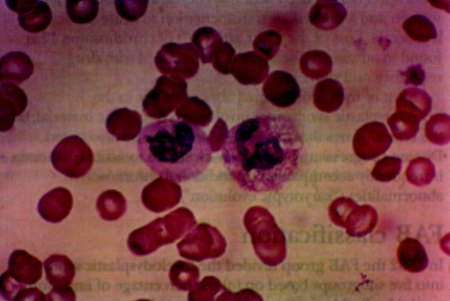

Peripheral blood smear will show cytopenias and dysplasia (e.g., hypogranular and hypolobulated granulocytes [pseudo-Pelger-Huet anomaly]).[16]Fenaux P, Haase D, Santini V, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Myelodysplastic syndromes: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021 Feb;32(2):142-56.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(20)43129-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33221366?tool=bestpractice.com

Additional laboratory tests include reticulocyte count, red blood cell folate, serum vitamin B12, and iron studies (serum iron, total iron-binding capacity, ferritin).[11]Killick SB, Wiseman DH, Quek L, et al. British Society for Haematology guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of prognosis of adult myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 2021 Jul;194(2):282-93.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.17621

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34137023?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: myelodysplastic syndromes [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[16]Fenaux P, Haase D, Santini V, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Myelodysplastic syndromes: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021 Feb;32(2):142-56.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(20)43129-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33221366?tool=bestpractice.com

These should be carried out to exclude other causes of cytopenias. Reticulocyte count is often low in MDS.[50]Juneja SK, Imbert M, Jouault H, et al. Haematological features of primary myelodysplastic syndromes (PMDS) at initial presentation: a study of 118 cases. J Clin Pathol. 1983 Oct;36(10):1129-35.

https://jcp.bmj.com/content/jclinpath/36/10/1129.full.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6619310?tool=bestpractice.com

Testing for viral infection (e.g., HIV; hepatitis B, C, and E; cytomegalovirus; parvovirus) can be carried out if there are risk factors for prior exposure.[11]Killick SB, Wiseman DH, Quek L, et al. British Society for Haematology guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of prognosis of adult myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 2021 Jul;194(2):282-93.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.17621

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34137023?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: myelodysplastic syndromes [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[16]Fenaux P, Haase D, Santini V, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Myelodysplastic syndromes: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021 Feb;32(2):142-56.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(20)43129-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33221366?tool=bestpractice.com

HIV infection can cause dysplastic bone marrow changes that are similar to those seen in MDS.[51]Katsarou O, Terpos E, Patsouris E, et al. Myelodysplastic features in patients with long-term HIV infection and haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2001 Jan;7(1):47-52.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2516.2001.00445.x?sid=nlm%3Apubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11136381?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Blood film showing normal neutrophil (right) and dysplastic neutrophil with agranular cytoplasm and hypolobated nucleusImage used with permission from BMJ 1997;314:883 [Citation ends].

Bone marrow evaluation

Bone marrow aspiration (with iron stain) and core biopsy are required for morphological, cytogenetic, mutational, and flow cytometric analyses.[15]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: myelodysplastic syndromes [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[47]Garcia-Manero G. Myelodysplastic syndromes: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2023 Aug;98(8):1307-25.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26984

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37288607?tool=bestpractice.com

These investigations confirm the diagnosis of MDS, and guide risk stratification and management.[15]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: myelodysplastic syndromes [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[47]Garcia-Manero G. Myelodysplastic syndromes: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2023 Aug;98(8):1307-25.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26984

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37288607?tool=bestpractice.com

[52]van de Loosdrecht AA, Kern W, Porwit A, et al. Clinical application of flow cytometry in patients with unexplained cytopenia and suspected myelodysplastic syndrome: a report of the European LeukemiaNet International MDS-Flow Cytometry Working Group. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2023 Jan;104(1):77-86.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cyto.b.22044

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34897979?tool=bestpractice.com

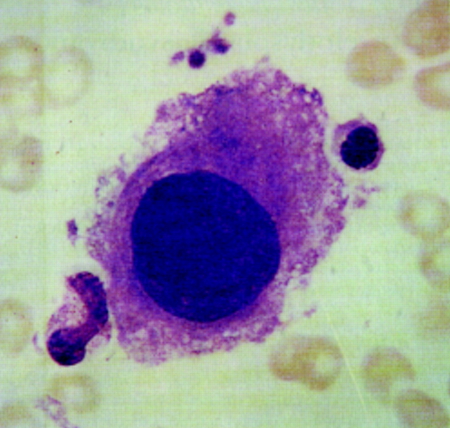

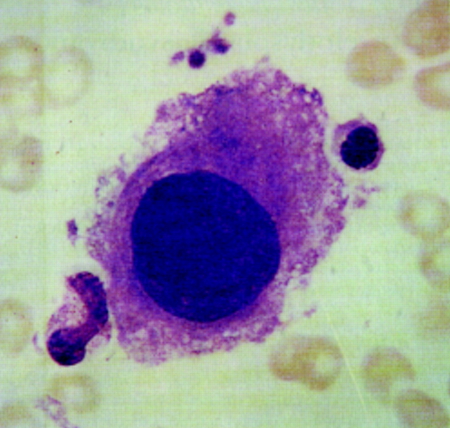

A diagnosis of MDS can be made in a patient with persistent cytopenia in the presence of one of the following three criteria: significant bone marrow dysplasia (≥10% in one or more of three major bone marrow lineages); blasts in the peripheral blood and/or bone marrow (<20%); or a clonal cytogenetic abnormality or somatic mutation.[1]Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization classification of haematolymphoid tumours: myeloid and histiocytic/dendritic neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022 Jul;36(7):1703-19.

https://www.doi.org/10.1038/s41375-022-01613-1

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732831?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian RP, et al. International Consensus Classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood. 2022 Sep 15;140(11):1200-28.

https://www.doi.org/10.1182/blood.2022015850

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35767897?tool=bestpractice.com

[11]Killick SB, Wiseman DH, Quek L, et al. British Society for Haematology guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of prognosis of adult myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 2021 Jul;194(2):282-93.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.17621

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34137023?tool=bestpractice.com

Biological features are more important than a strict blast cut-off value.[15]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: myelodysplastic syndromes [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Patients with blasts ≥20% should be assessed for acute myeloid leukaemia. See Acute myeloid leukaemia.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large mononuclear megakaryocyte in bone marrow of patient with MDS-del(5q)Image used with permission from BMJ 1997;314:883 [Citation ends].

Genetic testing

Genetic testing for MDS-associated cytogenetic abnormalities (e.g., -5, del(5q), -7, del(7q), del(11q), del(12p), -17, del(17p), del(20q)) and somatic mutations (e.g., DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1, TP53, SF3B1) informs the diagnosis and prognostic risk stratification.[11]Killick SB, Wiseman DH, Quek L, et al. British Society for Haematology guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of prognosis of adult myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 2021 Jul;194(2):282-93.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.17621

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34137023?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: myelodysplastic syndromes [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

The presence of certain cytogenetic abnormalities or somatic mutations (e.g., -7/del(7q), del(5q), and SF3B1) may establish a diagnosis without dysplasia.[1]Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization classification of haematolymphoid tumours: myeloid and histiocytic/dendritic neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022 Jul;36(7):1703-19.

https://www.doi.org/10.1038/s41375-022-01613-1

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732831?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian RP, et al. International Consensus Classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood. 2022 Sep 15;140(11):1200-28.

https://www.doi.org/10.1182/blood.2022015850

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35767897?tool=bestpractice.com

Genetic testing may be carried out on peripheral blood if bone marrow testing is not possible.

Patients with significant dysplasia who do not have a clonal cytogenetic abnormality or somatic mutation should undergo further evaluation to exclude a non-malignant cause of dysplasia.

Subsequent testing

Once a diagnosis is established, the following additional tests may be useful in certain situations.

Serum erythropoietin levels: can be measured to guide treatment with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents.[15]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: myelodysplastic syndromes [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[16]Fenaux P, Haase D, Santini V, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Myelodysplastic syndromes: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021 Feb;32(2):142-56.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(20)43129-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33221366?tool=bestpractice.com

[53]de Witte T, Bowen D, Robin M, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for MDS and CMML: recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017 Mar 30;129(13):1753-62.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5524528

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28096091?tool=bestpractice.com

Serum erythropoietin is usually elevated in MDS except in concurrent renal failure, in which case it is low.

Lactate dehydrogenase: has prognostic value and can be measured to inform risk stratification and management.[15]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: myelodysplastic syndromes [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[16]Fenaux P, Haase D, Santini V, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Myelodysplastic syndromes: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021 Feb;32(2):142-56.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(20)43129-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33221366?tool=bestpractice.com

Elevated lactate dehydrogenase is associated with poorer outcomes.[54]Wimazal F, Sperr WR, Kundi M, et al. Prognostic value of lactate dehydrogenase activity in myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Res. 2001 Apr;25(4):287-94.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2126(00)00140-5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11248325?tool=bestpractice.com

[55]Germing U, Hildebrandt B, Pfeilstöcker M, et al. Refinement of the international prognostic scoring system (IPSS) by including LDH as an additional prognostic variable to improve risk assessment in patients with primary myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). Leukemia. 2005 Dec;19(12):2223-31.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16193087?tool=bestpractice.com

HLA typing: useful if the patient is a candidate for haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, or if extensive platelet transfusions are needed or anticipated.[53]de Witte T, Bowen D, Robin M, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for MDS and CMML: recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017 Mar 30;129(13):1753-62.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5524528

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28096091?tool=bestpractice.com

Flow cytometry: can contribute to the diagnosis (by identifying dysplastic features and blasts) and prognostication. May be used (alongside STAT3 mutation testing) for the evaluation of a concurrent paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria clone, and possible large granular lymphocytic leukaemia.[3]Steensma DP, Bennett JM. The myelodysplastic syndromes: diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006 Jan;81(1):104-30.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16438486?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: myelodysplastic syndromes [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1