Approach

In most cases, there is no definitive method for making a diagnosis of a drug-related adverse reaction. In some cases, the probability that a drug has caused a clinical outcome can be assessed by considering certain features of the drug in relation to the adverse reaction. These include dose, time, and susceptibility factors. Most combine 5 criteria: challenge, dechallenge, rechallenge, previous description in the medical literature, and consideration of other possible causes. If feasible, these help to clarify the relation of the reaction to a specific drug. If in doubt, further testing will help to clarify the presence of a drug-induced reaction as well as the cause.

Age is not a helpful feature because drug-induced skin lesions can occur at any age.

The first step in evaluating a potential drug reaction is to diagnose the cutaneous eruption by clinical pattern. In determining whether the patient's current eruption could be related to a specific medication, the association increases when the use and frequency of this pattern of reaction with the drug has been determined.

Features of reaction types

Anaphylactic reactions, whether immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated or non-IgE-mediated, present with a range of signs and symptoms, depending on the intensity of the reaction. These include rhinitis and conjunctivitis; urticaria and pruritus; angio-oedema and laryngeal oedema; asthma and pulmonary oedema; nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain; faintness, lightheadedness, and a sense of impending doom; and tachycardia and hypotension (anaphylactic shock).

Erythema multiforme presents with a wide range of polymorphous, and often painful, erythematous. Maculopapular lesions are widely spread, so-called target lesions are typical, and less than 10% of the body is affected. Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), regarded by some as severe forms of erythema multiforme, involve respectively up to 10% and over 30% of the body surface area. In SJS, vesicles and large blisters can occur in the mucous membranes of the eyes and mouth. In TEN there is widespread desquamation. However, some regard erythema multiforme as a separate condition and distinguish minor and major erythema multiforme from SJS/TEN.

In DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; also called drug hypersensitivity syndrome) there is a maculopapular rash, fever over 38°C (100°F), abnormal liver function tests or evidence of other organ involvement, lymphadenopathy in at least 2 sites, and blood count abnormalities (lymphocytopenia or lymphocytosis, eosinophilia, or thrombocytopenia).[35]

Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis is characterised by fever and widespread small sterile pustules within large areas of oedematous erythema.[36]

Fixed drug eruptions are variable in presentation. Most commonly there is a pruritic, round or oval, sharply demarcated, red or purple, slightly raised plaque of variable size. There is usually only a single lesion, but multiple lesions can occur. A generalised reaction is rare and can include vesicles and blisters. The lips, hands, and genitalia are typically affected, and occasionally the oral mucosa.[37][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Palmar target lesions in erythema multiformeFrom the personal collection of Nanette Silverberg, MD, FAAD, FAAP [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Blistering targetoid lesions on the trunk, carbamazepine induced Stevens-Johnson syndromeKhoo AB, Ali FR, Yiu ZZ, et al. Carbamazepine induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. pii: bcr2016214926. Used with permission [Citation ends].

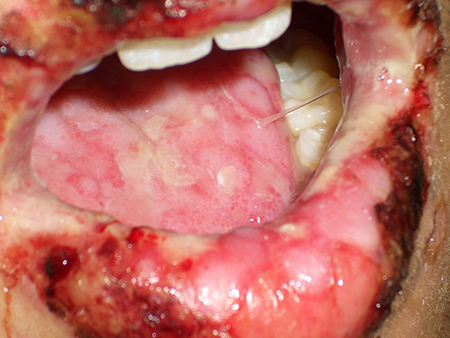

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Blistering targetoid lesions on the trunk, carbamazepine induced Stevens-Johnson syndromeKhoo AB, Ali FR, Yiu ZZ, et al. Carbamazepine induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. pii: bcr2016214926. Used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Oral and mucosal ulcerations, carbamazepine induced Stevens-Johnson syndromeKhoo AB, Ali FR, Yiu ZZ, et al. Carbamazepine induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. pii: bcr2016214926. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Oral and mucosal ulcerations, carbamazepine induced Stevens-Johnson syndromeKhoo AB, Ali FR, Yiu ZZ, et al. Carbamazepine induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. pii: bcr2016214926. Used with permission [Citation ends].

Lesion identification

Adverse drug reactions can cause any type of skin lesion. Common adverse skin reactions to systemic drugs include maculopapular skin reactions, urticaria and angio-oedema, the spectrum of skin lesions encompassing erythema multiforme (EM), SJS, and TEN; and fixed drug eruptions. EM can be described as annular erythematous rings with an outer erythematous zone and central blistering sandwiching a zone of normal skin tone. SJS is generally regarded as on a spectrum of disease with TEN (most severe). SJS is characterised by severe macular (atypical target) lesions that coalesce, resulting in epidermal blistering, necrosis, and sloughing; <10% of total body surface area is affected, and SJS can present with only mucosal involvement (e.g., in the conjunctivae and mucous membranes of the mouth). TEN is also characterised by severe macular (atypical target) lesions that coalesce, resulting in epidermal blistering, necrosis, and sloughing, but >30% of total body surface area is affected.

Less common reactions include acneiform eruptions, alopecia, bullous eruptions (pemphigus and pemphigoid), photosensitivity and phototoxicity reactions, purpura due to various causes, pustular eruptions (e.g., acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis), Sweet's syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis), and various forms of vasculitis. Contact dermatitis arises after the use of topical drugs and cosmetics.

DRESS, which is rare, is a systemic disease that can occur after exposure to many drugs, including anticonvulsants and sulfonamides. It usually occurs 1 to 8 weeks after exposure and consists of fever, a skin eruption, and multi-organ involvement. It may be one of a spectrum of allergic disorders that include such conditions as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, sulfonamide syndrome, and anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome. It has been associated with infection with human herpesvirus-6.[38]

Pruritus and pain, although symptoms of an adverse drug reaction, are indistinguishable from those occurring in non-drug-induced lesions.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Drug exanthem due to phenytoinPhotography courtesy of Brian L. Swick [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Typical lesions seen in acute or chronic urticariaFrom the personal collection of Stephen Dreskin, MD, PhD [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Typical lesions seen in acute or chronic urticariaFrom the personal collection of Stephen Dreskin, MD, PhD [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Angio-oedema of the lips in a patient who also has urticariaFrom the personal collection of Stephen Dreskin, MD, PhD [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Angio-oedema of the lips in a patient who also has urticariaFrom the personal collection of Stephen Dreskin, MD, PhD [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Stevens-Johnson syndrome: epidermal loss on soles of feetFrom the personal collection of Areta Kowal-Vern, MD [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Stevens-Johnson syndrome: epidermal loss on soles of feetFrom the personal collection of Areta Kowal-Vern, MD [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Initial phase of toxic epidermal necrolysis with diffuse erythema and vesicles that will evolve to full epidermal necrosisFerrandiz-Pulido C, Garcia-Patos V. A review of causes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:998-1003. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Initial phase of toxic epidermal necrolysis with diffuse erythema and vesicles that will evolve to full epidermal necrosisFerrandiz-Pulido C, Garcia-Patos V. A review of causes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:998-1003. Used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Palmar target lesions in erythema multiformeFrom the personal collection of Nanette Silverberg, MD, FAAD, FAAP [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Palmar target lesions in erythema multiformeFrom the personal collection of Nanette Silverberg, MD, FAAD, FAAP [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A 17-year-old male patient diagnosed with Stevens-Johnson syndrome due to azitromicine. Erosions and crusts on the lips with diffuse ulcers on the tongueFerrandiz-Pulido C, Garcia-Patos V. A review of causes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:998-1003. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A 17-year-old male patient diagnosed with Stevens-Johnson syndrome due to azitromicine. Erosions and crusts on the lips with diffuse ulcers on the tongueFerrandiz-Pulido C, Garcia-Patos V. A review of causes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:998-1003. Used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A 5-year-old female patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis with three suspected drugs (penicillin, ibuprofen, and paracetamol)Ferrandiz-Pulido C, Garcia-Patos V. A review of causes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:998-1003. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A 5-year-old female patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis with three suspected drugs (penicillin, ibuprofen, and paracetamol)Ferrandiz-Pulido C, Garcia-Patos V. A review of causes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:998-1003. Used with permission [Citation ends].

Time course

For initiation (priming), drug-hypersensitivity reactions require 5 to 7 days of exposure. Frequently, hypersensitivity reactions arise later than this (e.g., DRESS commonly arises after 3 to 4 weeks of therapy). After sensitisation, on subsequent exposure, hypersensitivity reactions within minutes for IgE-mediated allergic reactions and within hours for T-cell-mediated hypersensitivity reactions. Therefore, exposure time is central in establishing causality. Non-immune hypersensitivity reactions arise with a very variable time course and a few reactions occur very late, for example, lichenoid eruptions, which can take months or years to develop.[39]

History

In all cases, a full drug history, including dietary supplements and alternative medications, should be taken. Exposure to a drug within the previous few minutes or hours (acute allergic reactions) or up to 2 weeks before should suggest the possibility of a drug-induced lesion. Any drug can cause an allergic reaction; beta-lactam antibiotics, nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), muscle relaxants used in anaesthesia, sulfonamides and related drugs, contrast media, and gelatins (plasma substitutes) are commonly implicated. A previous similar reaction strengthens the likelihood of an association with a specific drug.

Hypersusceptibility reactions are dose-related at doses below the usual therapeutic range but not at doses within the therapeutic range. Collateral reactions occur at doses within the therapeutic range and the severity of the reaction varies with dose, while toxic reactions occur at doses above the therapeutic range. Lowering the dose (i.e., partial dechallenge) may result in disappearance of the adverse reaction. The absence of a dose-related reaction in the therapeutic range of doses suggests either a hypersusceptibility reaction or a cause other than a drug.[40]

Susceptibility factors

If the patient has a known susceptibility factor for an association between the suspected drug and the adverse event, a causative association is more likely.

Patients with the following history may have a higher rate of reactions to certain medications:

Cytomegalovirus or Epstein-Barr virus infections increase the risk of ampicillin and amoxicillin rash.

HIV infection increases the risk of hypersensitivity reactions to sulfonamides and structurally related compounds.

Specific human leukocyte antigen polymorphisms increase the risk of abacavir-, carbamazepine-, and allopurinol-induced reactions.

Adverse drug reactions to the Chinese medicine Shuanghuanglian injection are more likely in individuals with previous reactions to penicillins or sulfonamides.[41]

Dechallenge and rechallenge

Disappearance of the lesion after withdrawal of a suspected drug (dechallenge) increases the probability of a causative association; failure to resolve after withdrawal is against the diagnosis. However, non-drug-induced skin lesions can resolve coincidentally after withdrawal of a drug, and drug-induced lesions can persist despite drug withdrawal.

Recurrence of the lesion after rechallenge, if feasible, strongly suggests a drug-induced lesion. In cases of fixed drug eruption, the lesion will reappear at the same site and in the same form.

However, systemic rechallenge is not advised after allergic reactions. Drug challenges are generally contraindicated after severe cutaneous adverse reactions (DRESS, SJS/TEN, acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis) and other more severe non-IgE-mediated reactions (e.g., drug-induced liver injury or cytopenias).[42] Guidelines recommend shared decision making if the benefit of the drug outweighs the risk of performing a challenge in patients with a higher probability of true allergy or a history of more severe reactions.[42] In some cases, rechallenge can be placebo controlled, for example, photoallergic contact dermatitis might be reproduced by applying the suspected drug to skin on one side of the body and a placebo on the other and exposing both areas to light. Guidelines recommend considering placebo-controlled drug challenges for patients with subjective symptoms or multiple reported drug allergies.[42]

Rechallenge recommendations are available for specific drugs and drug classes (e.g., antibiotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, chemotherapy drugs, immune checkpoint inhibitors, biologicals).[42][43][44]

Confirmation of drug-induced adverse reaction

In a few cases, histological features of the lesion may suggest a drug-related cause. Infiltration of eosinophilic polymorphonuclear leukocytes may suggest a drug-induced lesion.

The following tests are indicated to confirm specific conditions.

Serum tryptase concentration is raised during the first few hours after an anaphylactic reaction.[45][46]

C4 measures should be taken during an attack in angio-oedema alone (no urticaria). If C4 is low, C1-esterase levels should be measured. Occasionally, C1-esterase function needs to be measured if the enzyme is not low but inactive.

Full blood count is usually normal in drug-induced lupus, in contrast to abnormal findings in systemic lupus erythematosus. In drug-induced lupus, anti-histone antibodies are found.

Skin tests (prick tests, intradermal tests, patch tests) can occasionally be useful in diagnosing allergic reactions retrospectively, especially contact dermatitis. Skin tests may also be useful adjuncts for establishing causality and cross-reactivity for delayed hypersensitivity reactions.[42] However, skin tests are limited by low sensitivity and thus results should be interpreted with caution, particularly in the setting of severe reactions given the imperfect negative predictive value. Due to the risk of relapse, skin tests for DRESS should be delayed for at least 6 months after the acute reaction and/or 1 month after discontinuation of corticosteroids.[42]

In vitro tests such as drug-specific IgE, basophil activation test, lymphocyte proliferation assay, and enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISPOT test) can be helpful, particularly in the case of negative skin tests or severe life-threatening reactions (e.g., anaphylactic reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics).[47][48] However, these tests are largely research tools at present and should be interpreted only in conjunction with patient history and clinical findings; specialist advice should be sought.

Other identifiable causes

Identification of another cause may allow a drug-induced cause to be ruled out.

The Naranjo scoring system

Some diagnostic features of common cutaneous drug reactions have been summarised in the Naranjo scoring system.[49]

The following scores give the likelihoods of an adverse reaction:

≥9 = definite

5 to 8 = probable

1 to 4 = possible

0 = doubtful.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: The Naranjo scoring systemNaranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245 [Citation ends].

The Bradford Hill guidelines

Austin Bradford Hill outlined some of the diagnostic features of common cutaneous drug reactions as guidelines for suggesting cause and effect.[50] These guidelines have been adapted and renamed as follows:[51]

Direct evidence

Size of effect not attributable to plausible confounding

Appropriate temporal and/or spatial proximity (cause precedes effect and effect occurs after a plausible interval; cause occurs at the same site as the intervention)

Dose responsiveness and reversibility.

Mechanistic evidence

Evidence for a mechanism of action (biological, chemical, mechanical)

Coherence (with current scientific knowledge).

Parallel evidence

Replicability (i.e., rechallenge)

Similarity (to previous reactions).

This system can be used to help clinicians decide whether causality is likely in an individual case; the more criteria that are fulfilled, the more likely the association.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer